A DEBATE IN AN ORCHARD.

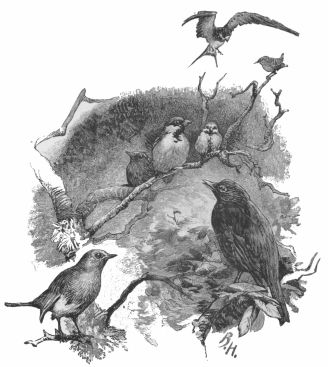

IT was one of those midsummer evenings which to the discontented seem almost too long. In the orchard the old birds had finished finding the young ones their supper, and the long labours of the day were over. The swifts were flying, and screaming with delight as they flew, round the old church tower, and the swallows were gliding less noisily in and out of the long shadows of the apple-trees; but most of the dwellers in the orchard had taken a quiet perch, and were singing, or dallying in some pleasant way with the last half-hour of daylight, until it should be time to go to roost.

A blackbird, a robin, a sparrow, and a blue titmouse found themselves together on a single tree. They were old acquaintances, for they had lived together in the orchard and garden the whole winter; friends, in the proper sense of the word, they were not, for they differed a good deal in their opinions, and had quarrelled nearly every day in the winter over the crumbs which had been put for them outside the farmhouse windows. But they contrived to put up with one another, and had been so busy with their young of late, that all ill-feeling had passed away from their minds.

“Well,” said the sparrow, “here we are again. Upon my word I wish the sun would set; there’s nothing more to do.”

“Why don’t you sing?” said the robin.

“That’s a stale joke,” was the answer. “And your song is getting stale too, Mr. Robin; you’ll have to leave it off a bit soon.”

“One should not sing too much,” observed the blackbird. “I wonder you robins don’t get tired of hearing yourselves. It’s too hot to sing this evening: spring is the time for that. Let us do something else to amuse ourselves.”

“Let us see who can hang from a bough best with his head downwards,” said the blue tit; and he instantly performed the feat with great agility. The sparrow, being in want of something to do, tried to imitate him, but he couldn’t do it a bit, and made himself ridiculous.

“What a lubberly creature!” said a swallow, who had paused in her flight through the orchard to rest for a moment at the end of a dead bough of the same tree. “Are you so hard up for something to do? Why don’t you have a debate? There was a debate going on in my barn the other evening, and very amusing it was. Old Squire Wilmot was in the chair. He told the men and boys that they were going to have a debate once a month to sharpen their wits, and—”

(“That’ll take a long time,” put in the blue tit.)

“And the young squire was going to propose a motion himself that night.”

“What do you think it was about? Bird’s-nesting! He said it was cruel, I believe; and some one else said it wasn’t; and there they were chattering away all the evening. But I had young to attend to, and of course I couldn’t listen, even if it had been worth while. Why don’t you have a debate? I dare say you wouldn’t talk quite such nonsense. Good evening.” And off she went, without waiting for an answer.

“That’s not a bad idea,” said the blue tit; “only I don’t much care to imitate Man. What a lumbering animal it is! However, if we are to have a debate, why not debate about him? We shall all have something to say on that subject, anyhow.”

“Very well,” said the Robin, who had a way of taking things into his own hands, “very well, we will discuss Man. But first we must elect a president. I am willing to be president, if you like. Our family has encouraged Man for many centuries, and we ought to know something about him by this time!”

There was silence for a minute. The Robin was not so popular in the orchard as to be elected at once by acclamation. At this moment the Swallow returned to her twig, just to see how they were getting on, and was informed of the difficulty.

“Oh, by all means elect Robin,” said she; “they always elect some respectable person president. They like some one who looks better than he talks. Presidents don’t make speeches as a rule; they sit and look grand, like the beadle in the church where I nested last summer. And now I think of it,” she added, “that beadle had a red waistcoat just like Bobby’s; so he had.”

And off she went again.

“Bother that bird,” said the Robin; “she’s like a wild-rose bush, all prickles and no caterpillars. I won’t be president if I am not to be allowed to speak. Let the Blackbird preside; it would just suit his capacity.”

“I don’t pretend to be better than I am,” said the Blackbird in his mellowest tones; “but we had better vote at once, it will soon be dark. Each of you imitate the voice of the bird you wish to elect. All the birds in the orchard shall be welcome and eligible: Starling, Nuthatch, Creeper, Wren, Flycatcher, Chaffinch. Now then, one, two, three——”

A variety of strange sounds were heard, so strange and discordant that the farmer’s wife looked out at her back-door to see what could be going forward. But while it was still going on, there was heard at the top of all the din the clear shrill song of a Wren from a heap of old sticks by the wall.

“The very bird for you,” said the Swallow, alighting once more on her twig. “He’ll only have to turn on his loudest song to stop the speakers if they get tiresome or lose their tempers. He’ll be like the organ in that church I was telling you of; it was put there to prevent the singers being heard, and it did its business very well. Yes, yes, elect the Wren; he’s small, but he’s afraid of no one. And in some countries they call him king.”

She flew to the heap of sticks, and returned with the Wren, who took his station on a prominent bough, cocked his tail very high, and sang his very loudest.

“That will do capitally,” said the Swallow. “Turn on that whenever they make fools of themselves, and you’ll have the debate to yourself after all.”

And she was gone again, leaving them another pleasant little keepsake. But they were too eager for the debate to begin, to mind much what she said, and they all consented to accept the Wren as president.

“I appoint the Blackbird to open the debate,” said the Wren, who had been duly instructed in his duties by the Swallow. “Let the Blackbird state what motion he will propose.”

“I will propose,” replied the Blackbird, “that too close an association with Man is degrading to the race of birds.”

“I won’t speak on that motion,” said the Robin, “I consider it personal.”

“So do I,” said the Sparrow; “grossly personal and insulting.”

“What’s insulting?” said the Swallow, who was back again for the fourth time. “Oh, most insulting to birds who use men’s buildings for their nests! Look at me and the Sparrows, see how refined and elevated we have become through ages of association with man! One doesn’t like to talk of one’s self, but I put it to you whether the Sparrow’s charming, fairy-like grace, dainty appetite, and chastely brilliant colouring, can well be ascribed to any other cause? But dear me, I never meant to make a speech. Good-bye; don’t quarrel, and, above all, don’t be sarcastic; it’s a habit I abhor.” And she glided away once more.

“That’s one for you, Philip,” said the mischievous Blue-Tit to the Sparrow. “Let her have it back again next time, my dear boy; have a repartee ready. Make haste, you have no time to lose.”

“All right,” said the Sparrow. “Don’t fidget so. I’ll think of my repartee during the Blackbird’s speech.”

“Silence!” called the president. “Trrrrrr-lira-lira-lira-la-trrr! I must call on the Blackbird to put his motion in another form, as it is considered personal.”

“Well,” said the Blackbird, “I move that Man is an animal as useless as he is pernicious. That’ll suit everybody, I hope.”

“Won’t do,” said the President. “You must

And the Blackbird began his oration.—

have three adjectives, and they must all begin with the same letter. It always is so, I assure you; the Swallow told me so just now, and she heard it all going on in the barn. The young squire proposed that bird-nesting was mean, mischievous, and malevolent; and a very sensible motion too.”

“Very well,” said the Blackbird, “then I move that man is a mean, mischievous, and malevolent animal. Will that do for you?”

“Excellent!” said every one. “Go on, and be quick.”

“Be as quick as you can,” said the Robin, “or there won’t be time for my speech.”

“Silence!” cried the president. “I call on the Blackbird.” And the Blackbird began his oration.

“Man,” he said, “is in the first place mean. This may be thought perhaps too obvious a proposition to need proof. I need but ask you to look over the orchard wall into the kitchen-garden yonder. What do we see there? Gooseberry-bushes, currant-bushes, covered with delicious fruit; I know it, for did I not try the flavour of every one of them daily till yesterday? And now, now, just as their juices are mellowing, each of those trees has been covered over with a most vile and treacherous netting! If time were not pressing I could easily produce statistics to show——”

“What are statistics?” asked a Flycatcher deferentially.

“A new kind of earwigs,” said the Blue-Tit promptly. “Don’t interrupt. What a flow of eloquence!”

“I could produce statistics to show,” continued the Blackbird, “that those gooseberries and currants would be sufficient to feed scores of blackbirds for several weeks together. Think of what is here lost to the world through the meanness of Man!

“The raspberries indeed are not netted; but, friends, I would ask you, if you can control your feelings for a moment, to look in the direction of the raspberry canes. There you may see—I can hardly bear to mention it—the dead bodies of two cousins of mine, who lost their lives through the meanness of Man, in the exercise of their natural rights and appetites. Shot, cruelly shot, by the farmer’s son, and exposed to view to frighten us!”

Here the speaker was overcome by emotion, and paused for a few moments.

“Go on,” said the Robin, “or you’ll never get to the end of your speech. Why do you want to eat fruit? Caterpillars are much better.”

“Order, order,” cried the President. “Trrrrr-lira-lira-trrr.” The Blackbird resumed the thread of his argument.

“I do not care,” he said, “to notice unseemly interruptions at a moment when such painful thoughts have obtruded themselves on my mind. I will proceed in the next place to show that man is mischievous. I need not dwell on this point; the fact is known to you all. The word is far too mild. Which of us has not lost a nest, or seen our young caught and killed, either by man himself, or by his parasite the cat? They are the only two animals who kill for the pleasure of killing. Of the two, as you know, man is far the worst; he is more cruel and more awkward than a cat. A cat is agile, nimble, even beautiful to look at, terrible as she is; and she does not steal the nests which we have taken such infinite pains to build. A kitten is a pretty and even a harmless little creature; but the young of man is horrible to contemplate. What dreadful noises he makes! What a contemptible object he appears! Though compelled by nature to keep to the ground and go along on two stumps, he will sometimes climb trees if he can but see a chance of doing us a mischief. You hear the awkward creature crashing through the branches; you are forced to fly for your life, and to leave your young and eggs to the monster’s mercy! I will not harrow your feelings further, but will content myself with the simple assertion that cats are far better.

“I now come to the third point. Man is malevolent. Man, that is (as some of you may not understand the word), is evilly disposed towards us. His evil deeds are the result of an evil will. I see you are getting impatient, so I will only give you a single instance of this, which shall at the same time be a crushing proof. As I was enjoying myself in a gooseberry bush a day or two ago, before the meanness of man displayed itself in those malicious nets, I heard the farmer’s wife singing to her baby as she sat on the seat under the pear-tree close by me. I kept very quiet, as you may imagine, and heard all she said. Fancy my horror when I heard her begin—

“Four-and-twenty blackbirds, baked in a pie.”

Thus you see from his earliest years—from the egg, I might have said, had Fate destined him for a higher sphere than that he occupies—is Man taught malevolence towards the birds. His mother whispers the poison even into his baby ears; he grows up thinking of baked blackbirds; and though no doubt in later life he prefers what he (luckily for us) calls bigger game, the malevolence of his mind towards us singing-birds is ever on the increase. Such then is Man: mean, mischievous, malevolent; a creature that might indeed, in many ways be our equal if he could but restrain his evil instincts; but as he is, degraded, demoralized, and dangerous.”

This burst of eloquence took the company by surprise; they never suspected the Blackbird of possessing such genius. There was general applause, which was broken in upon however by an unlucky incident. The Robin, when the Blackbird stopped, had instantly taken possession of the orator’s bough, a prominent one directly below that of the president. The Sparrow, seeing this, and being always ready to pick a quarrel with the Robin, had flown to the bough with angry screams, and was trying to turn out the new orator. Robin fought as might be expected of him, the other birds were preparing to join in, the President was calling for order, and whistling his very shrillest, when up came the Swallow once more. She preferred to be absent during the speeches, but looked in, she said, to see if their wits were getting sharpened.

“What!” she exclaimed, “quarrelling already! Ah, I see, no wits to sharpen, so try claws and beaks instead!”

“Where’s your repartee, Philip?” said the Blue Tit. But before the repartee was forthcoming the Swallow was gone again.

The Swallow’s remark had the result of calming the troubled waters; and as the Robin had been first on the bough, the President called on him to speak.

“I do not pretend to eloquence,” said the Robin; “but I know what I think, and shall say it as well as I can. Some things the Blackbird has said I agree with; but birds who habitually eat fruit must expect man to make war upon them. Now between my family and man there has been for ages a treaty of peace—a treaty which man keeps up, because he knows how much it is to his advantage; and which we keep up, not only for our own benefit, but because we hope that in due time we may improve and elevate man. He is powerful, but he is by nature vicious, as the Blackbird has observed. Well, we hope we have done something in the past, and may do something in the future, to rid him of his baser qualities.

“You probably do not know how this treaty of peace came to be made. I will tell you as shortly as I can. Long ages ago there was a king of this island who married and had two lovely children, a boy and a girl. These children went out one day to play in the wood near their papa’s palace, and lost their way. Night came on, and they lay down to sleep; they never woke up again, but lay there dead and cold. We saw them there; we covered them with leaves, and paid a last tribute to their beauty and innocence. The king and queen found us at the good work, and then and there made a treaty with us, which has lasted in this island ever since. By this treaty it was ordained—

“1. That man should not use his strength or his dreadful engines of destruction to kill or molest any robin.

“2. That man should abstain from taking the nest of any robin; but that he should be allowed to take one egg now and then, if he should feel his evil desire for collecting getting the better of him.

“3. That man should put food outside his windows for the robins in the winter, and should take care that it was not all eaten up by sparrows.”

(Here the Sparrow asked the President whether the speaker was in order in introducing such offensive matter into his speech. The President decided that as the Robin was quoting a historical document, no offence could be taken.)

“These,” said the Robin, “are the most important clauses of the treaty. On our side it was agreed:

“First, that the robins should abstain as far as possible from damaging man’s property, i.e. his fruit or his corn, and should do him as much good as possible by eating the grubs and caterpillars in his gardens.

“This clause has been faithfully kept by us, to our own lasting benefit as well as that of man. I would advise all birds who insist on eating fruit and corn to observe how excellent are the results of a grub and caterpillar diet.” Here the Robin paused a moment, and displayed his portly red waistcoat in all its glory to the audience. Then he went on:—

“Secondly, it was agreed that the robins should take up their dwelling as far as possible in the haunts and gardens of man, and should sing to him, not only in the spring or the summer, but all the year round, as often as they should feel able and disposed to do so. This clause has also been faithfully kept by us, and the result is, in my humble opinion, that we are now not only the most regular, but the most versatile and accomplished singers who affect the haunts of man. I will not however press that point, as I see some of you seem to dissent.

“Now you will observe that though, as was right and proper, this treaty was framed much to the advantage of the robins, both parties to it have certainly gained by it, and man, who has on the whole kept it fairly well, has learnt from it to respect and to care for at least one family of birds. I would therefore conclude by asking you to consider, before you pass this motion, and commit yourselves to perpetual enmity to mankind, whether it would not be wiser to follow our example, and make a lasting peace with him. I am convinced that you would do yourselves no harm; and I am still more firmly convinced that you would find a pleasure in joining us in the good work of raising mankind to a higher level of life, and a better appreciation of the superior creatures around him.”

There was but faint applause when the Robin left the orator’s bough. He was not popular, as has been remarked; and he was always posing (so they thought) as a superior person. And now he claimed superior wisdom on the ground of his intimacy with man! The Sparrow, who had listened very impatiently to his speech, sprang up at once to the bough, and began in loud and rather angry tones:—

“What rubbish people can talk! The motion itself is absurd, the Blackbird’s speech was silly, and the Robin’s speech shows that his whole race, from the beginning, have, as I always said, been the victims of a delusion. You none of you know the least bit how to deal with man. We Sparrows found out the secret ages ago, and look how we have prospered! Talk of treaties! why in the name of all that’s feathered should any one want to make a treaty with man? I say it’s ridiculous. That isn’t the way to do it. Only idiots would do that.”

“Order, order!” said the President. “I really must call on the honourable speaker to control his feelings and modify his expressions.”

“Very well,” said the Sparrow; “but really when one hears such blathering nonsense talked—”

“Order, order!” called the President, and whistled his loudest. “The honourable Sparrow must positively address himself to the point, and not be rude, or I shall call on him to retire.” Thus admonished, the Sparrow continued in milder tones:—

“Well really, you know, what I was going to say was, when the President interrupted me, that man is here to be made use of, not to be made treaties with. We found out long ago how to make use of him, just as we found out long ago how to use the martins’ nests. (Loud cries of ‘shame.’) Shame, indeed! Rubbish! If you want to prosper, take what you can get, and don’t go to make treaties about it, or fight for it more than you can help; lay your claws into it when no one’s looking, and make sure of it. You’ll be the better, and no one else the wiser. Man sows corn: we take it; thousands of us live on it nearly all the year round. Man sows peas: we take them—at least all the juicy young ones—he can have the old ones for himself. Man plants crocuses: we found out that there was good food inside the blossoms, and we take them. Man puts bread-crumbs outside his window, in fulfilment of his treaty with the robins, no doubt: we take it nearly all. Man does no end of other things, and we take advantage of them all. And see how it pays! We sparrows are the rising race. We increase every year by thousands; we go everywhere; we despise nothing; we eat anything; and we have a good time of it. All you other birds will disappear in time; there’ll be no room for you, and nothing left for you to eat. Man will remain, but only to support us; we must have peas and corn, so man must remain. And may he ever remain,” added the orator, in a burst of eloquence, “the infatuated slave that he is now!”

“Bravo!” said the twittering voice of the Swallow, who had returned again, attracted by the Sparrow’s loud tones. “Capital! and how pleasing to think that there’s one animal in the world who’s a greater blockhead than a Sparrow!”

“Now then, Philip,” said the Blue Tit, “here’s your chance; where’s that repartee?”

The Sparrow ruffled his feathers, and pecked at them, as if half expecting to find the repartee there; but not succeeding, he was just about to fly at the Swallow and drive her from her perch, when lo! a little maiden of seven years old came running and dancing into the orchard, and made for the very tree on which the birds were perching. The Blackbird went off instantly with a loud cackle; the Sparrow chattered excitedly and went off too; the Robin departed very quietly to another part of the orchard; and the Starling, Chaffinch, and others made off as fast as they could go. Only the Swallow and the Wren were left; neither of them were a bit frightened.

“Now by the salt wave of the Mediterranean, which I have so often crossed,” said the Swallow, “I am glad we were spared that repartee.”

“Now by the sweet juices of a green caterpillar, which I have so often sucked,” said the Wren, “I am glad we have come to the end of this folly. Good-night; the sun has set. There’s a bat; I really must get home.”

The Swallow was left alone. “Well,” said she to herself, “once is enough; I’ll not ask them to have another debate. I’m glad I didn’t hear the speeches. We swallows trust in man, and he loves us; but we cannot understand him, nor he us. But we live all our lives by love and trust,” said she, as she opened her wings to fly; “as for understanding, that must wait.”

She was gone, and the orchard was silent again.