A QUESTION BEGINNING WITH “WHY.”

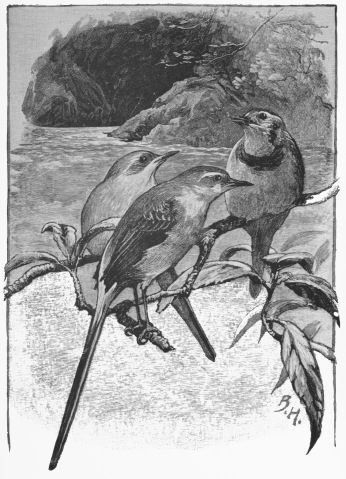

ONE warm summer afternoon two young men were leaning out of a window, smoking their pipes, and enjoying a lazy half-hour. The window was one of a long row in the garden-quadrangle of an old gray Oxford college; and you looked out of it on a beautiful close-shaven lawn, bordered with flower beds, and inclosed on one side by one of watery Oxford’s many streams. This lawn, in the summer, is never without its family of water-wagtails. Here there is no fear of bird-nesting boys, and comparatively little peril of cats; and the turf is mown so often and so closely, that even the youngest bird can find his food there without the least trouble. And there they were that July afternoon, sometimes running so quickly that you quite lost sight of their little black legs, then stopping suddenly and moving their tails rapidly up and down for a few moments, then pouncing upon some unlucky insect on the grass, or perhaps pursuing it in the air with a quick fluttering of wings and tails; and all the while uttering that contented little double-note of theirs, which seemed to say to the occupants of the old panelled rooms above them, “This is real happiness; we take what comes, and ask no questions; we don’t puzzle our heads over Philosophy, and Biology, and Constitutional History, and Economical Science. Why, even you wouldn’t be trying to find out a reason for everything, if you weren’t afraid the Examiners were going to ask you for it! Come down here and lie on this beautiful lawn in the shade, and forget all about the why and the wherefore. Take things as you find them; there are no Examiners about just now!”

The two young men were not thinking of the wagtails; but neither were they thinking of anything else in particular, and the invitation to go and lie on the lawn found its way somehow into their temporarily vacant minds. They put on their flannels and their boating coats and went and stretched themselves at full length under the cool shade of an acacia. There they lay quite quiet and happy, and were for some time so silent that the wagtails ventured up quite close to them without any sign of fear.

One was a poet; at least his friends thought him one, and as he himself was not quite sure that they were right, it is not impossible that he had a few poetic streaks in his nature. The other was a student of science, and spent most of his time in cutting earth-worms and frogs into beautiful little slices, and looking at them through a microscope. They had a liking for each other, because neither fully understood the other’s thoughts and ambitions; so there was plenty of room for comfortable silence, and cosy human companionship.

At last the silence was broken by the poet. He spoke as much to himself as to his friend.

“It’s very puzzling,” he said.

“Very,” said the man of science, without taking his pipe from his lips, and not in the least knowing what the other was thinking of. At this moment a young wagtail took a long run, and stopped, in all the innocent fearlessness of youth, within half-a-dozen yards of them. There was a pause again.

“I never can make out,” at last pursued the poet, “why Shakespeare wrote no more plays during the last years of his life. He wasn’t old, and he must have had plenty of time at Stratford.”

“He probably liked better to lie in his garden and think of nothing at all,” said the other. “But I don’t see why you want to find out. Much better to leave the poor man alone.—”

“Why, what do you do all day up at the Museum?” asked the poet. “I thought you were always trying to find out something or other. I dare say you’d like to find out why that bird wags its tail,” he added, as the young wagtail made another little run forward, and stood there just in his line of vision with her tail going gently up and down.

“Why it wags its tail?” said the man of science: “you just catch it and bring it up to the Museum, and we’ll soon tell you why it wags its tail. It’s only a matter of nerves and muscles, and spinal cord you know, and all that sort of thing. The professor would soon put you up to all that. But that reminds me that I said I’d help him with some specimens this afternoon, and it’s past three o’clock.” And up he jumped, and ran off to get his hat, startling the young wagtail, which flew away to the other end of the lawn.

Little did these two lads know how much trouble and anxiety their conversation was to bring upon the inhabitants of that peaceful lawn. That young wagtail had heard what they said; for birds certainly understand what men say. Do they not carry secrets? People should be careful what they say in their hearing.

Now up to this time this young bird, like her brothers and sisters, had never given a moment’s thought to what she did, or what she looked like. Nor had she noticed what the others did, or what they looked like. She wagged her tail, but she did it without thinking of it; as for asking why she did it, that was very far from the mind of herself or any of the family. And now she suddenly became aware, not only that she did it, but that it was possible to ask why she did it.

She looked at the others: they were all doing it, every other minute or so. Then she wagged her own tail, to see what it felt like, now she knew that she did it. And now she began to feel very ill at ease.

“What can it all be for?” she said to herself. “Even that man didn’t seem to know all about it. There goes my tail again! Really, it wags almost without one’s knowing it. There can’t be any harm in it, I should think, as father and mother are doing it too. But why do we all do it? I don’t see any use in it. There it goes again, before I ever thought of holding it still. I must really go and ask mother about it.”

She flew up to her mother, who was in a very happy and contented frame of mind, having brought up her young so prosperously in the midst of plenty and comfort.

“Mother,” she said, “will you please tell me why we all wag our tails?”

The prudent mother was rather taken aback; but after taking a little run and flight, to collect her mind, she returned answer very decidedly,

“We don’t wag our tails. Who’s been putting such fancies into your head?”

“A big man on the other side of the lawn said he should like to know why we wag our tails!”

“Men are blockheads,” said the mother. “Don’t you go near them, Kelpie, on any account. They know nothing about us. I tell you we don’t wag our tails, and I won’t be contradicted. Go away, child, and look for beetles.”

Kelpie went away, but she could not throw herself into the beetle-catching with the same ardour as before. Whenever she looked up she saw some one’s tail moving, and she got more and more puzzled over it. At one moment she thought she was rid of the puzzle: “Mother says we don’t,” she reflected, “so of course, at least I suppose, it’s all my fancy;” and she began to search for food. But the next minute she felt that her own tail was going up and down, and back came all the puzzling thoughts as lively as ever again. At last she lost all confidence in her mother, and resolved to ask her father’s opinion.

“What does my little Kelpie want?” said he, as the young one came flying up.

“I want to ask a question, father. Mother says we don’t wag our tails, but a man I heard talking said we did. Which do you think is right?”

“Your mother’s sure to be right, my dear,” said he; “I never, never knew her wrong. Never,” he said with warmth, and wagging his tail to emphasize his words. “Believe all she says, and do everything she tells you.”

“But father, dear, you’re wagging your own tail now as fast as you can!” cried Kelpie.

“I do it sometimes when I am a little excited,” he said, taken by surprise. “But don’t you think any more about it, Kelpie, there’s a dear; it would vex your mother so, you know. And promise me you won’t say anything about it to your brothers and sisters. Will you promise? All sorts of dreadful things might happen, you know, if one went about asking questions like that.”

Worse and worse for poor Kelpie! Her mother had plainly told her an untruth; her father had half admitted it to be so, and had seemed quite frightened at the idea of such questions being asked. What could the mystery be? Kelpie’s little mind was all in a flutter.

She went on as usual however from day to day, and said nothing to the rest of the family about the troubles of her mind. At last however it struck her that she might question other birds, though it was clearly no good consulting her own kith and kin. A thrush who frequented the lawn, and always looked very wise, seemed likely to be a friend in need; so she took an opportunity one day, when the others were out of hearing, of asking him her question.

The thrush put his head on one side, and listened very attentively while Kelpie was speaking. “Now,” thought she, “I shall get an answer. Oh, what a relief.” She stood quite still and waited patiently.

“Ah,” said the thrush, quite suddenly, “I thought I heard it!” And he made a quick dig into the earth with his bill, and pulled out a long worm by the tail. Kelpie watched while he swallowed it,—it did not take more than a few seconds—and then said timidly, “If you please, sir, I don’t think you heard me, I—”

The thrush again put his head on one side, stood quite still in an erect attitude, and seemed absorbed this time in Kelpie and her troubles.

“I asked you a question, sir,” said she again; “I’m very much afraid I’m troubling you, but I do so want to find out the answer.”

“I’ve found it,” said the thrush, as suddenly as before; and he darted his bill into the ground again, pulled out another worm, and this time flew away with it. Kelpie was left alone, a sadder but not a wiser bird.

She was greatly disheartened for a time. At last however she determined to try once more. An old jackdaw, with a very gray head, used to come very early of a morning on to the lawn when no one was about except a few starlings. Kelpie didn’t think the starlings looked very promising, they were so restless, and there were so many of them together. But the jackdaw, she had heard her parents say, was the wisest bird in the whole garden; so she watched her chance, and approached him one morning very modestly.

“I fear, sir,” she said, “that you will think me very bold, but I have heard of your great wisdom, and I thought you would be good enough to explain something to me.”

The jackdaw looked at her, not unkindly. “Have you asked your parents?” he said.

“Yes, sir, but they won’t explain it to me.”

The jackdaw shook his head. “Probably they couldn’t,” he replied. “Wagtails are very ignorant birds. But I’ll give you a bit of advice. If anything puzzles you, go and listen in chimneys. There are no fires there now, and you can hear what men and women say. That’s how my family has come to be so wise. But you must get into the habit of it, you know; you must spend a good deal of time there; it may be years before you get an answer to your question.”

“But perhaps you could answer my question,” said Kelpie; “because, you see, you might have heard the answer yourself in a chimney.”

“No doubt, no doubt,” said the jackdaw gravely. “But, my dear child, what would be the use of knowledge if we were always giving it away, like the lecturers we hear from these Oxford chimneys? No, no; you go and listen in chimneys (you’re black and gray, like us, and it wouldn’t spoil your feathers), and when you find out the answer to your question keep it safe and don’t part with it. That’s the way to get wise.”

The jackdaw made a grave bow, and flew up to the college tower. Kelpie flew on to the college roof, perched on a chimney, and looked down. It smelt very nasty and was quite dark; however she tried to descend a little way, but she got so frightened that she came up again directly, and gave up the attempt for good.

“I must give it up,” she thought; and with a deep sigh she joined her family at their breakfast on the lawn. She found them in a state of some excitement, for after breakfast father Wagtail was to make an important announcement.

“My dears,” he said, when they had all gathered round him, “the summer is almost over; you are all old enough to shift for yourselves, and our little party must now break up. We may very likely meet again, but your mother and I, having brought you up as well as we can, will not be responsible for you any longer. You are free to go when and where you like. Some of you may like to cross the sea, and visit foreign countries; some may prefer to take the chance of a mild winter here. Do just as you like: but we advise you all to travel more or less, and get acquainted with the world. Now good-bye, and good luck to you all.”

Kelpie was overjoyed at hearing this news. She had not been happy for a long time; now she could go out into the wide world, and try to find out the answer to the question that so weighed on her mind. She bade adieu to the rest at once, and started off by herself in high spirits. She would be very careful, she thought, as to whom she questioned, and would try and find some really friendly and open-hearted adviser.

She was so occupied with all the new and strange things she saw—the rivers, the ploughed fields, the hills and downs she passed over, and so determined not to be put upon any more by thrushes and jackdaws, that autumn had set in before she ventured to address a single bird on the subject she had at heart. But one day in September she was enjoying herself by the side of a rapid little brook which ran through pleasant meadows, when she caught sight of a very long tail going up and down, up and down. The bird it belonged to was hidden behind a stone in the stream. She watched, and saw a gray wagtail come from behind the stone, and fly with graceful curves a little further on, then she saw another bird join him, and stood in speechless admiration of these beautiful creatures, so slender, so gentle-looking, and so beautifully covered with gray above and yellow beneath. But what most fascinated her was the motion of their long tails, which were never for a moment still.

She went up and introduced herself. They received her kindly as a distant connection, and said she was welcome to the brook; and in their company she remained for the greater part of the day, before she summoned up courage to open her heart to them.

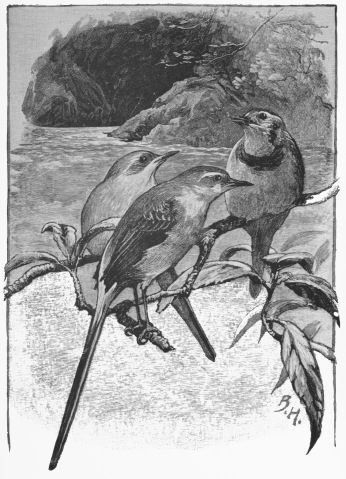

“You are very kind and good,” she said at last, “and I think you must be very clever too. Would you mind telling me, as I see you wag your own tails so constantly and so nicely, why you do it, and why all our family do it too? If you only would, I should be so happy and grateful; you can’t think how it’s been troubling me!”

The gray wagtail looked at his wife, and she looked at him, and they seemed to nod to one another in rather an odd way.

“Dear, dear!” said the wife,—“what a sad pity!”

“Oh, dear me, dear me!” said the husband, “how sad! And such a nice young creature too! What can we do for her?”

The wife shook her head silently; Kelpie felt dreadfully ashamed of herself. What could be the matter?

“Please tell me if I have done anything wrong,” she said.

“My dear,” said the wife very kindly, “I fear you are not very well. If I were you I should get advice as soon as possible. I strongly recommend the kingfisher, who lives yonder up the brook; I believe he is very clever in cases like yours, and he eats fish, which is very good for the brain, you know. You’ll be sure to find him if you wait about a little. I am very sorry, my dear, but we must go away, for they say it’s extremely catching.” And followed by her husband she flew away down the stream.

“Would you mind telling me, as I see you wag your own tails so constantly and so nicely, why you do it?”—

Kelpie was now quite frightened. Something seemed to be altogether wrong with her. She began to think she must have eaten something that fatal day on the lawn, which was growing up inside her, and causing her all this trouble. She hastened away up the brook, and after searching for a while, she found the kingfisher sitting on a bough overhanging the stream. She addressed him without any apology, for she wanted dreadfully to know what was the matter with her; and she poured out her whole sad story from beginning to end. The kingfisher sat quite quiet on his bough, and listened with great attention.

“Yours is a very curious case,” he said when she had done; “a very interesting case indeed. I should strongly recommend constant change of scene; a tour on the Continent, now, would be very likely to do you good. Frequent application of cold water could hardly fail to be useful; keep to your usual insect diet, but vary it a little with the small crustaceans you will find in the stream; I can speak warmly of their value from my own experience; they are an excellent tonic. This is what I advise you to do; but if you should find yourself still troubled, I should go to some one who has made a special study of these cases, which I have not.”

“Whom would you recommend?” said Kelpie nervously. She felt quite sure that she would have to go to the specialist, because the kingfisher had told her to do exactly what she always did. She changed her scene, she dabbled in the water, and she lived on flies and anything she could get in the brooks.

“You might consult a crow,” said the kingfisher. “They are the most highly developed of all birds, and are nearest to man. There is one who lives in a wood a mile or two higher up. You can mention my name if you like.”

“Thank you very much,” said Kelpie; “but would you be so very kind as to tell me what is the matter with me?”

The kingfisher sat still for another moment as if in deep reflection; then he made a dart downwards into the water, dived, brought up a fish, and glided with it in his beak round a turn of the stream and disappeared.

Kelpie went at once in search of the crow. She felt that whatever came of it, she must find out what was wrong with her. After a long search she found the crow sitting on the dead branch of a hollow old oak-tree. The bones of a young rabbit, which he had been dissecting, doubtless with a scientific object, lay on the ground below. Kelpie felt very frightened when she looked at this huge black bird, with his enormous black bill, curved into a sharp hook at the end. But there was no help for it; she felt she must go through with it. As she approached, he gave a low hoarse croak.

“What do you want here?” he said.

“The kingfisher recommended you, sir,” said Kelpie, “as a—”

“The kingfisher recommended me, did he?” said the crow. “The impudence of these small practitioners! But never mind the kingfisher: pray go on, my time is limited.”

“I have been greatly troubled,” said the trembling Kelpie, “with a desire to find out—”

“I see,” said the crow decisively. “Yours is a very simple case. What did the kingfisher say about it?”

“He said I was to have change of scene, and cold water, and—”

“Exactly,” said the crow. “He’s quite wrong. You would certainly have died if you hadn’t come to me. You are suffering from a tumor inquisitivus esuriens of a very virulent kind. I can take it out for you.” And he began to sharpen his beak on the bough.

“Is it a very—a very dangerous operation?” asked Kelpie.

“One and a half per cent survive it,” said the crow.

“I think I would rather not have it done,” said Kelpie.

“Very well,” said the crow; “but you won’t live through the winter. And if you don’t make haste and go,” he added fiercely, “I’ll do it whether you like it or not!”

Kelpie flew away as fast as she could, and never stopped till she was a good mile away, and she left that part of the country the very same day. She resolved to ask no more questions, but to pass the rest of her life as well as she could, and die contentedly in the winter. As for foreign travel, that was plainly no good now; so she thought she might as well return to the pleasant place where she had been brought up, try and find some of her relations, and get a little help and comfort before she died.

Slowly and sadly she made her way towards Oxford. It was now getting towards November, and the country was growing sad with falling leaves and creeping mists; but that was quite in keeping with her own feelings, and she did not notice the absence of the sun, or feel any sorrow at the browning of the trees and fields; only just one little gleam of sunshine brought her a moment’s pleasure, when she saw the spires of Oxford catch it in the distance, as she came flitting up the river-bank from the point where she had struck the Thames.

About two miles below Oxford she met a boat coming easily down stream, with two human beings in it; one was sculling, the other steering. She stopped on the towing path at a safe distance from them, and waited till they should pass. They were within a few yards of her, and she was just going to take flight again, when the one who was steering called out to the other in a voice she remembered only too well,

“Easy a moment, Poet, I want to look at that bird.”

Kelpie stood quite quiet, except that her tail was moving up and down with great rapidity. The Poet looked round and saw her.

“Aha, Chick,” he said (his friend was called Chick because he spent so much time in studying the development of fowls in the egg), “do you remember that hot afternoon when we lay in the garden and watched the wagtail? I suppose you’ve found out by this time why they wag their tails?”

“No, I haven’t,” said Chick. “Nor have you found out why Shakespeare wrote no plays the last three years of his life.”

“Quite true,” said the Poet; “but then I don’t work at the Museum, where they find out everything!”

“No, they don’t,” said Chick; “you’re quite out of it. Spare your irony for once. I’ll just tell you what happened that afternoon. I kept thinking of that bird all the way up to the Museum after I left you, for when I came to think of it, that tail-wagging was rather an interesting point. So when I got there, I asked the Professor about it. Well, he was a bit bothered with his specimens that afternoon, and rather short in his temper, and I was late, which made him worse; so he gave me a lecture on the spot. He’s a good lecturer, you know, even when he’s quite serene: but when he’s savage there’s no one like him. He comes out with home-truths then, and blows you into little bits. I wish you would come and let him demolish you, Poet, it would knock such a heap of rubbish out of your poetic head.”

“Very likely,” said the Poet: “but what nonsense did he knock out of your head? Plenty there to operate upon.”

“I quite allow it,” said Chick. “That is a scientific view of education which you poets would do well to act on. But the Professor growled at me when I asked him why wagtails wag their tails, and said there would have been some use in asking how they do it. And then he took me into his room, and showed me diagrams, and explained the muscular system of a bird, which I never understood before; and he kept me a whole hour there, till at last he got quite sweet again. And after that he said he’d give me a piece of advice, which I’ll hand on to you, and I hope it will do you good.”

“I’m sitting at your feet,” said the Poet, “go on.”

“Well, what he said was this: ‘You young fellows are a deal too anxious to get hold of a reason for everything; and I dare say you think it a fine thing to come and try to puzzle us with questions. Now what you have to learn here at present is not reasons, but facts. Leave alone for the present these questions that begin with the word why; there are many of them that can never be answered, as far as I can see, or they can only be answered by getting together and properly arranging a great quantity of facts. Your wagtail question is just one of this kind. You have no more business to be asking me such a question, than a young wagtail has to be asking its parents why it wags its tail. You stick to facts, and don’t ask why a thing is, until you know altogether and exactly that it is and how it is.’

“And I’ve been sticking to facts ever since,” added Chick; “and you’d much better do the same. Pull on, Poet; and whenever you see a wagtail think of what I’ve told you, and your poetic brain will be all the better for it.”

“There she goes,” said the Poet: “I wonder why she stopped so long. I really think she was listening to us.”

“I might have spared you the Professor’s sermon,” said Chick. “Pull on, Poet; go ahead. Here we are running into the bank while you’re asking questions that begin with why!” And they dropped slowly down the stream.

The Poet was quite right. Kelpie had been listening—drinking in every word of the Professor’s sermon. A delicious and soothing feeling grew upon her at each sentence, and when it was over she sprang upon her wings with a sense that a whole load of trouble had been taken off her mind.

“They were all wrong,” she said to herself: “thrush, jackdaw, kingfisher, and especially that wicked old crow. Why couldn’t they tell me the truth? But that’s a question that begins with why, and I must stick hard to facts.”

Kelpie kept hard to her facts, and found her happiness in doing so. She kept to flies, beetles, and small crustaceans; she kept hard to her husband when the pairing-time came, and to her eggs and young; she kept to the laws of her kind, and left the questions that begin with “why” to the Professor and his species.