THE OWLS’ REVENGE.

(A TALE OF BIRDS AND MEN.)

I.

IN May all woods are beautiful; but of all the woods I know, there is none on which the month of bluebells so freely lavishes her delights, as on the ancient and unkempt wood of Truerne. The blue carpet spread in every clearing, the gray-green oak-stems rising softly out of the blue, the fleecy clouds of spring, seen gently moving eastwards through the ruddy young leaves overhead, can never be forgotten by any one who has rambled here for a whole May-morning. No trim park-paling shuts in Truerne wood; its outskirts are set about, in these sweet spring days, with an untidy maze of “whitening hedges and uncrumpling fern,” with stretches of gorse and trailing bramble, with dense thickets of blackthorn where the nightingale builds his nest and sings unheeded. It is all this wild setting of the woodland, as well as the freedom of the wood itself, that makes it so dear to such of its human neighbours as love quiet and solitude, as well as to the birds and beasts that find home and happiness in its shelter.

Of the few human beings who haunted it a few years ago, old Oliver the woodman was the only one to whom it had wholly yielded up its secrets; and when one day he was found under his favourite old oak-tree, wrapped in a slumber from which there was no awakening, we felt that the good genius of the wood had vanished, leaving no successor. But on the morning of that 16th day of May on which my story begins and ends, old Oliver was still vigorous, and had risen at daybreak in order to finish his work early. He meant to set forward about midday for the neighbouring town on the hill; for it was fairday, or “club” as we call it in these parts, at Northstow, and he wished once more to buy a fairing for the rheumatic old wife sitting by the chimney-corner at home.

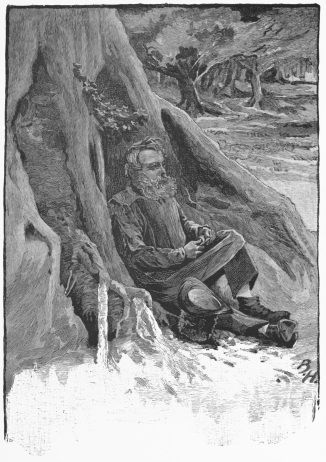

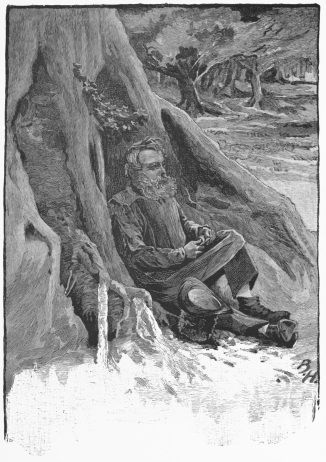

He is sitting, and eating his dinner, at the foot of his favourite oak, which is separated by a few yards of bluebells and undergrowth from one of the grassy rides, or “lights” (as we call them) which intersect the wood, and let sunshine and fresh air into its tangled depths. It is his favourite tree, partly because its gray-lichened stem divides on one side, as it nears the ground, into two big root-branches which leave a comfortable space between them—a mossy arm-chair of which he only knows the comfort who has toiled since daybreak without ceasing; and partly because the tree is old, as old as the abbey of Truerne which once stood under the shadow of the wood in the meadows below; and because it is hollow enough to be the home of a family of brown owls, whose ancestors had been tenants of the wood long before the monks became its owners. These owls were some of Oliver’s best friends; he seldom saw them, nor they him; but, boy and man, he had known them for more than half a century, and knew them well to be discreet and quiet creatures, who did no harm and gave no trouble to any one but vermin. There was a silent, mysterious sageness about their ways, which suited well with the old man’s humour.

He is sitting and eating his dinner at the foot of his favourite oak.—

As he sat there eating and resting, the silence of the wood was broken by the sudden squeak of a pig; and half turning his face in the direction of the ride, Oliver saw an uplifted sapling descend on the back of the squeaker, who raised his piteous voice again, and rushed onwards down the path with his companions. They were followed by the owner of the sapling, a tall man in a long greasy coat of a yellowish colour; his face was fat and ruddy, and out of it there looked two small cunning eyes, which followed the movements of his pigs to right and left with merciless swiftness. It was the kind of face which men seem to acquire who spend their lives in driving pigs and driving bargains, and who are ever bullying animals and browbeating their fellow-men. Close at his heels was another smaller man, a little wizened, discontented farmer, whom Mr. Pogson, with his natural imperativeness, had pressed into his service in driving his pigs to Northstow fair. An umbrella, as decrepit as the farmer himself, was the weapon he used, without much energy, when a pig chanced to stray in his direction.

Oliver kept very quiet as they passed: he did not like Pogson, and had no respect for Weekes the little farmer. At last they had disappeared down the ride, and after sitting a while longer, listening to the sibilant notes of the wood-wren overhead, and watching the squirrels and the nuthatches who were fellow-owners of the tree opposite to him, he rose with something of a sigh,—for he was unwilling to exchange the quiet wood for the noise and worry of the fair,—and stepped into the bridle-path to set out on his walk.

“Are ye ganging to the fair, Oliver, ye lonesome auld dog?” said a grave but friendly voice in a Scotch accent. It was the voice of Mr. McNab the keeper, who without his gun, and in his best velveteen, was on his way to look out for a spaniel-puppy or two to fill vacant places.

“Ay,” said Oliver simply, and they walked on side by side; Mr. McNab’s serious gray eyes glancing here and there through the wood, and Oliver’s earnest and rather wistful gaze kept steadily on the bluebells at his feet, as was his wont when walking. Neither of them was a man of many words or many friends; nor had they spoken to each other half a dozen times a year since the Scotchman came into the neighbourhood. Yet each of them felt, as they went along, that he had a reasonable man beside him.

II.

IT was high tide at Northstow fair: the broad, sloping street was crowded with pens of sheep and pigs, and resounded with the noises of oppressed animals, with the loud voices of their tyrants, and with the hideous braying of the organs which of late years have added new attractions to the merry-go-rounds. Old Oliver, soon wearied of the crowd and the hubbub, had bought his wife’s new shawl early, and was about to turn his steps homewards, when it occurred to him that it would be as well, if circumstances were favourable, to get a comfortable shave before leaving.

The Northstow barber had a double shop, one window of which was decorated with his own wigs and perfumery, while the other showed caps and bonnets, and was the domain of the milliner, his wife. As Oliver passed this latter window, and was about to step into the shop, his eye caught the well-known form of an owl—a young one, perched in an uneasy attitude on a lady’s hat. He stopped to look at it, and then discovered a placard, conspicuously placed just underneath the hat, and bearing the following inscription:

Wanted at once, by a London firm,

ONE THOUSAND OWLS![7]

The old fellow stood rooted to the pavement, spelling out this placard again and again. What could it mean? and what the owlet on the lady’s hat? As he lingered, two men came up behind him, and there jarred suddenly on his senses the bud coarse voice of Mr. Pogson, already a little thickened by frequent glasses of ale and brandy. “Wanted, one thousand howls!” spelt out Mr. Pogson, slowly. “How much a-piece, now? There be scores on ’em in Truerne, be’nt there, Oliver, eh?”

“Ay, there be brown uns in the wood, and white uns in my barn, and in Highfield church tower,” said the feeble voice of Mr. Weekes the farmer.

At this moment the barber, relieved for a moment from his duties, came out on his doorstep to enjoy the cheering sights and sounds of the fair.

“Good day, Mr. Pogson,” he said. “How’s the pigs? Coming in for a shave? Low prices in pigs to-day, so I hear tell. Ah, you’re looking at the notice? My wife brought it down from town yesterday. There’s a chance for making money now!”

“What do they want ’em for?” said Mr. Weekes.

“What do they give for ’em, you mean,” said Mr. Pogson with some contempt.

“What do they want ’em for?” answered the barber, shirking Mr. Pogson’s question. “Why you haven’t got any pretty daughters, Mr. Weekes, or you’d know that by this time. Look at that there owl on the bonnet! Why, bless you, ’tis all birds now with the ladies in London—and in the country too for the matter o’ that. Birds on their hats, and birds on their dresses; and a very pretty taste too, in my opinion. What’s prettier, now, than birds? Think of their songs, Mr. Pogson, and all their pretty ways! Why when you sees ’em a fluttering about on the ladies’ hats in town, you could a’most believe as you was out in the country seeing the little creeters a-flying round you and singing! And now it’s all owls, I take it. Such softness o’ feathers, you see, such wings, such——”

“But what’ll they pay for ’em?” asked Pogson impatiently, tired of the barber’s talk.

“Fancy prices, sir, fancy prices,” said the barber; “why there’s a fortun’ in that placard! There’s birds o’ paradise selling in town—so my wife tells me—for fifty guineas a-piece, and there’s kingfishers and woodpeckers fetching a mint o’ money. I tell you even blackbirds and such like brings in something, for they dodges ’em up with other birds’ wings, or dyes ’em red and green, as pretty as can be. And now here’s a run on owls, you see; can’t get enough of ’em. Half-a-sovereign a-piece for the best ones, I think it was she told me. If pigs is down, Mr. Pogson, why owls is up, you see. Want a shave then? Come along, gentlemen, I’m free.”

“There be scores on ’em in Truerne wood,” said the pigdealer again to Weekes, as he preceded him into the shop; but catching sight of Oliver, who had shrunk away from the pair, and stood at a little distance riveted by the barber’s speech, Mr. Pogson added, “There’s that old tree by the ride: Oliver’s armchair, the Highfield folks calls it; there’s owls there now, and young ’uns as well, I’ll be bound. Ain’t there now, old soft-head?” And he made a playful cut at Oliver with his sapling as he went up the steps.

The old man was seriously alarmed. That these two men would be ready to meddle in the wood for the sake of a few guineas, or even a few shillings, if they had the chance, he knew very well; and the fact of the placard being there on fair-day was quite enough to set all the gun-owners in the neighbourhood owl-hunting. As he turned away from the window, he caught sight of the tall form of Mr. McNab sauntering through the fair, and regarding its various follies much as a grown-up man looks at the frolic of a pack of children just let out of school. He went after him quickly, and touched him on the arm.

“Mr. McNab! Mr. McNab!” said he, with earnest and imploring eyes, “there’s mischief up there; there’s mischief in the barber’s shop. There’s a placard out for a thousand owls, and they’re going to shoot ‘em in Truerne wood!”

“They might do waur,” said the keeper, not at all taken aback.

“ ‘Tis hard as Lunnon folk can’t leave us alone,” continued Oliver with a rueful face. “They’ll cut the wood down next and burn it for charcoal; I’ve heard talk on it afore now. But I’ll be in my grave before then, if so be as my prayers be granted.”

“They winna do that,” said the keeper; “dinna fash your auld head with sic notions. And we maunna hae the owls killed oot either, or we’ll be owerrun with rats in a year or twa. When the cat’s awa—ye ken. But what for is a’ this about owls, I wonder? Are they gaun clean doited in Lunnon then?”

And leaving Oliver, Mr. McNab walked up to the barber’s shop, and after looking at the milliner’s window, he went in, and did not come out again while Oliver remained within sight.

The old fellow waited a while, and walked about the fair; but he saw no more of McNab, and had to turn his face homewards without a word of reassurance. As he passed through the narrow passage, thronged with hard-faced men and boys, which divided the pens of crowded pigs and sheep, it made him wince a little to see Mr. Pogson, his ruddy face still ruddier, and his sunken little eyes sparkling with drink and with unwonted expectations of wealth, cutting at the hind-quarters of his newly-bought pigs with the sapling, shouting in a hard voice to greasy friends, and looking at every one who came near him as if they had better mind what they were about. For old Oliver he had a profound contempt; and as the old man passed him, he caught the pig that was nearest him at the moment such a cut with his switch, that its squeaks resounded through the street; it tried to escape over the backs of its fellows, who all with a loud chorus of squeaking rushed to the further side of the pen. Which so pleased Mr. Pogson that he turned to the old man with a wink, as if to say, “Now you see the proper way to treat animals.” But Oliver had passed on quickly.

III.

OLD Oliver trudged down the road from the little town on the hill, with his fairing under his arm, thinking of his old wife sitting in her chimney-corner, and of the old days when he bought the pretty young farm-servant her first fairing, in that same town and on that very same day in May, some five-and-forty years ago. Straight before him were the Cotswold hills, and on their slope he could see the spire of Highfield church, and further down and nearer was the great dark mass of Truerne wood, hiding the hamlet where he had lived all his life. The sight of the wood made him think of the owls, and he unconsciously quickened his pace, as if to make haste and see that all was right with them as yet.

Down the long sloping road he went, and then turning off by a bridle-path, passed through another wood—not his, and therefore no place for dallying in—and crossing the river by an old flood-beaten bridge, took his way through a wealth of buttercups that gilded his old boots with yellow dust, to the further side of the water-meadows, where his own beloved wood came down in gentle slopes to the valley. Evening was coming on and the light was subdued; all was quiet and peaceful unless a nightingale broke out suddenly in song from a thicket, or the voice of the chiff-chaff rang out from overhead. Over the bluebells the shadows were lengthening, and against their deep blue, as it mingled in the distance with the blue of the sky peeping through the branches, rose the straight and darkening stem of many an ancient tree. What a change from the noise and worry and ill-dealing and cruelty of the fair!

When he came to his own old oak he paused and listened; but no sound was heard but the song of the wood-wren in the higher foliage.

“ ‘Tis all right as yet,” he said to himself; “they’re not astir so early as this; but maybe they’ll be hooting when Pogson and the pigs come along later, and then they’re marked birds; the warrant ’ll be out against ’em. The Lord deliver them out of the hand of the Philistines,” said the old fellow, quite aloud. “I’ll get a bit of supper, and come and have a look presently”; and he went on up the ride.

Close behind him was the gamekeeper. Mr. McNab, finding that there were no spaniel-puppies at the fair, had no further reason to stay there; for he had a poor opinion of the people of those parts, and did not care to listen to their stupid talk, or to help them to drink bad beer. Moreover during his visit to the barber he had satisfied himself that his domains were really in danger of being invaded by unsportsmanlike clod-hoppers in search of owls; and the more he thought of it, the more impossible it seemed to have fellows like Pogson roaming about in his woods with firearms. It was bad enough to have pigs driven through your wood every fair-day, though that could not be helped where there was a right of way for man and beast; but he had reason to suspect Mr. Pogson of other still more objectionable practices, and at all times disliked the man as a noisy, bullying lout.

So he had left the fair soon after Oliver, only stopping at a shop in the outskirts of the town to buy a good-sized twist of strong cord. He did not stay to look at the view, or to sit on the bridge and watch the water, or to admire the bluebells when he came to Truerne wood. Mr. McNab was a man of a practical mind, and a swift walker; and he had nearly caught up Oliver when he arrived at the old oak-tree, so that he just heard the old fellow’s ejaculation about the Philistines, and then saw his smockfrock retreating up the ride. The Scotchman stopped and watched it disappear.

“Yon auld Oliver has mair gude sense,” he said to himself, “than a’ these blathering gowks o’ pigdrivers; and he kens his Bible too! A wee bit too saft—mair backbane, mair backbone! But he’s no sae doited as the rest!”

The sun was almost setting, but the owls in the old oak were still silent. “They’ll be hooting in an hour or twa,” he said, as Oliver had said it before him; and drawing the twist of cord from his pocket, he stepped aside among the bluebells to the oak-tree. Plenty of young ground ashes were shooting up among the flowers, and with the help of these, and of a low hazel bush or two, he contrived to fasten the cord in a pretty tight circle round the tree-trunk, at a distance of some half-dozen yards from it, and about a foot and a half from the ground. There being still plenty of cord, he looked about for a log of wood, and finding one not too heavy, he tied the cord round it, and hoisted it up on a low branch of the big tree, on the side nearest the ride, just balancing it at the junction of one gnarled bough with another, so that a strong pull at the string would easily bring it down. This done, he fastened the other end tightly down to his circle below, and then paused, with a face of extreme gravity, to contemplate his apparatus.

Suddenly his severe features relaxed. There had shot across his memory a certain scene, when as a bare-legged callant playing on his native braes, he had devised just such a booby-trap to catch another boy, with a view of securing for himself a certain nest in which eggs were about to be laid. The grim features of Mr. McNab relaxed, I say, and in his solitude in the wood he burst out into a hearty ringing laugh.

“At bairn’s wark in my auld age! And what wad the Dominie say? Wad I be for a crack wi’ the tawse, or the knuckle-end of the auld crab-stick at hame, eh!”

Mr. McNab lit his pipe, the better to resume his ordinary composure; and puffing at it with lips which now and then a convulsive movement almost compelled to laughter, he strode away through the wood to his own dwelling on the further side of it.

IV.

AND now the wood was left once more in profound peace. Since old Oliver passed through it the shadows had grown still longer, and from the west there now came a flush of sunset through the boughs, turning the blue carpet into one of deeper purple; while against the fading light the great tree-trunks stood up solemnly, slowly blackening as their shadows died away. Here and there a wood-pigeon broke the stillness in the boughs, or a nightingale broke out into a flash of song, and ceased again as suddenly; but the owls in the old tree began to bestir themselves in soft silence, and reserved their hootings until they should have procured a meal for the downy nestlings in the deep warm hole. But beware, O ye owls and owlets, for the Philistines are at hand, and the warrant of the ladies is out against you!

As the last hues of sunset died away on the Cotswold hills there came through the wood unlucky little Mr. Weekes; small in person and small in acres; discontented with his dealings at the fair, and with things in general, and ready for any project that might put a pound or two into his pocket without actually endangering his limbs or his liberty. As he passed the great oak, a large creature flew noiselessly over his head in the direction of the tree, and woke up Mr. Weekes’ memory, which had been halting in the slough of his discontent.

“Ah, the owls!” he thought. “Half-a-guinea a-piece, did he say? Well, it might be, if there’s a run on ’em; and that fellow Pogson said he was coming here first thing to-morrow morning to shoot ’em; but I’ll be even with the prosperous fat brute.”

Mr. Weekes thought of the morning’s pig-driving, into which he had been compelled by Pogson’s superior force of character; of the two ribs of his wife’s umbrella which he had broken on the back of one wayward squeaker; and of the long detour he had taken when leaving Northstow, to avoid falling again in with the pig-driver, and being once more driven to drive.

So he went home to his rickety little homestead beyond the wood, and reached down his old gun from its place above the chimney-piece; only yielding to the injunctions of his wife that he must eat a bit o’ supper first, and that if he must be for shooting owls, he should begin by shooting the one which was stealing all their young pigeons. Obedient as usual, though querulous, Mr. Weekes presently took up his station in his yard, watching the dovecote and the darkening sky; but luckily for the pigeons, whom the owls were nightly protecting from their enemies the rats, no owl made his appearance for a full half-hour after Mr. Weekes had given them up in despair, and had carried off his gun to the wood in hopes of better luck.

Meanwhile Mr. Pogson, after purchasing some dozen or so of fine porkers, and a bottle of brandy to help him in the arduous task of getting them home safely, began in the late afternoon to drive them down the long high road towards the wood. The pigs were lively, and their owner began to be a little unsteady on his legs—a sensation which he more than once sought to correct by a draught of strong ale at a roadside public-house. The remedy did not have the desired effect, and his progress became slower and slower; but in spite of all obstacles, and by dint of extreme severity and a lavish outlay of bad language, he contrived to conduct himself and his charges across the bridge and the meadows to the edge of the wood without serious mishap, arriving there about the time at which Weekes was prowling in his yard after the barn owl. The bottle of brandy was by this time more than half empty, and the wood was as dark as pitch.

If Mr. Pogson had been in full possession of his wits he would hardly have tried to force his way through the wood, and would have avoided the bridle-path, and taken his pigs a couple of miles round by the road; but he had gone like an unreasoning animal in the way he was accustomed to, and now it was too late to turn back. He took another pull at the bottle, switched the nearest pigs, and pulling himself for a moment together, forced his drove into the narrow ride, trusting that they would follow their noses and keep to the open path.

In the dense black darkness and stillness, a sleepy and a sickly feeling came over Mr. Pogson’s usually hide-bound senses, from which he was only for a moment awakened by a sudden movement of the pigs in front of him. Whether it were a badger in the path, or a prowling fox that had frightened them, certain it is that at this moment they all faced about, and rushing with loud squeakings past the legs of their driver, vanished in a general stampede away into the wood.

Mr. Pogson stood aghast, and leant against a tree-trunk for support. The noise of the pigs died away, and he was alone—alone in blank darkness. Even pigs are company, and now he would have given a good deal for the companionship of a single one of his victims. There was a singing in his ears, a cold sweat on his hard brow; he felt quite unable to go further; his head swam.

Suddenly he heard a voice from overhead—a gentle voice, reproachful and somewhat hollow and ghostly—

“Whoo? Tu-whoo?”

Mr. Pogson felt a creepy sensation, and would have cast himself to the ground and hidden his face in the bluebells, but again the voice asked—

“Whoo? Whoo? Tu-whoo?”

“Pogson o’ Highfield,” cried the belated man in answer. But in still more reproachful accents, the voice demanded for the third time—

“Whoo? Tu-whoo?”

“Pogson o’ Highfield, pig-dealer,” cried the wretched man in stuttering accents; “a man as never did no harm to nothing in all his life!”

“Whoo? Whoo?” said the voice, seeming to retreat, and urged to follow it by some mysterious influence, Mr. Pogson staggered forward a few paces. But he had hardly left his tree for more than half a minute, when something caught him on the shins and tripped him up; at the same moment he received a violent blow on the head which, added to the effects of the brandy, stretched him quite unconscious on the ground. There he lay in the darkness, with the bottle slipping out of his pocket, while the mysterious voice continued to question him in vain from the old oak-tree overhead.

And now, but for the voice, all is silent again for a few minutes. Stay, who is this coming down the “light,” betraying his presence by the crackling of a dry twig beneath his boot? It is Mr. Weekes, bent on further profitable destruction; who would not have ventured himself in the wood after dark for fear of ghosts and other terrors, but is now urged to unwonted courage by the hope of gain and by the companionship of his old gun. He is making for the tree where he saw the owl at sunset.

As he advanced deeper into the dead blackness of the wood, Mr. Weekes began to feel a slight uneasiness, which was soon uncomfortably increased by strange noises on his right-hand, as of weird creatures making towards him through the underwood. But he was now close to his tree, and he could hear the hooting of the owls that were to be his prey. He was in the act of raising his gun, ready to fire when an owl should cross the bit of sky-line open above him, when the noises increased to his right, and with a terrific crackling and confusion an army of terrible creatures burst out upon him into the ride. All his courage fled. With a yell of fear he discharged his gun at the advancing foes, and then throwing it at them as a last resource, took to his heels and ran from them. But he had not run many yards when he tripped first over a heavy body, and then over a tightened cord, and losing at once his balance and his senses, Mr. Weekes swooned outright.

V.

“DID ye hear the gun then?” said the keeper to Oliver, as they met a few minutes later at the entrance to the wood. “There’s mischief here, forbye at the barber’s. Tak’ yon big stick, mon, and gang ye on wi’ the lantern.”

They went softly down the ride together, neither speaking again. Presently the keeper stumbled over some solid body lying in the grass, and Oliver, applying the lantern to it, discovered the corpse of a pig. The keeper whistled softly, and turned it over with his foot.

“Lawfu’ spoil,” he whispered, “lawfu’ spoil. Ye shall taste Pogson’s bacon yet afore ye die, Oliver!”

Then they found the gun, which Mr. McNab, now in his element, seized as further spoil, and gave to Oliver to carry instead of the big stick. And now he turned aside for a few yards to see what other sport his bairn’s tricks of that day might have brought him. Oliver followed close at his heels with the lantern.

“Whoo! Tu-whoo!” said the owl overhead.

“Ay, ye may weel hoot at ’em,” said the keeper, as the lantern revealed the prostrate forms of Mr. Pogson and Mr. Weekes; the latest arrival lying across the other, and seeming to embrace him with one arm, while the hand of the other was thrust into a tuft of faded primroses.

Oliver and McNab regarded this spectacle for a few moments in silence. Then Oliver, catching sight of the bottle slipping from the pig-dealer’s pocket, turned his wistful eyes on the Scotchman.

“Mr. McNab,” he said, “I’m an old man, and maybe as I won’t be woodcutting here much longer; but don’t you—for my sake don’t you” (here he shyly laid his wrinkled hand on the keeper’s arm), “let such sodden brutes as these come along and take the lives of innocent creatures—creatures as God above loves, and has made me for to love too—and all for a few shillings, or maybe guineas, and to please the ladies in Lunnon as don’t know what a wood be like, nor what creatures lives their lives here. I’ve known this tree for more nor fifty year, but the owls ha’ known it belike for five hundred; and now, afore I’m dead, the warrant’s out agen them. The fine ladies wants their feathers, but they don’t know what they’re doing—they don’t think what they do, Mr. McNab. ’Tis fashion, I take it, only fashion, and it’ll blow over in a bit if you’ll but stop ’em now. I’m an old fool maybe, but God knows I’ve none too many to care about, or for to care about me, but my old woman, and beside her there’s none but these birds and beasts in the wood. And the peace of it, and the quiet of the life in it! Don’t you let it be rooted up, Mr. McNab, nor the wild beast of the field devour it!”

The keeper slapped him on the back of his smockfrock, and then seized him by the hand. “Oliver, my auld lad,” he said, “ye’ve just saved them out o’ the hand of the Pheelistines! And ye shall never want for friends to care for ye, be they owls or be they McNabs!”

And this was the story that old Oliver used to tell, with many a kindly word of respect for his friend the keeper, till one day, as I said at the beginning, death came upon him painlessly under that very tree, while the cuckoo sang in the distance, and the chiff-chaffs two notes echoed from the sunny end of the wood. How he came to know what happened to Mr. Pogson and the pigs is more than I can tell; probably the owls told it to him, or it may be that the conscience-stricken pig-dealer revealed to him alone the story, as to one who understood, as none else did, the mysteries of Truerne wood.

However that may be, it is certain that the enemy never again invaded his paradise. The owls were never disturbed, and by some mysterious agency the placard disappeared almost at once from the barber’s window. Mr. Pogson never passed through the wood again, and finding that distorted versions of his adventures were abroad in Highfield (where they are still told with relish by the winter fireside), he removed to a village some miles away, a milder and more merciful man. Mr. Weekes too was not long in giving up his farm, and disappearing entirely from the neighbourhood. In peace the owls and Oliver lived out their days under the grave but kindly guardianship of Mr. McNab the keeper; and when I last passed through the wood it showed no signs of the presence of the Philistine.

THE END.