CHAPTER XII

Mabel's Astonishing Discovery

THE campers rose the next morning without suspecting that a very strange thing was about to happen; or that Mabel, who was still in disgrace because of her habit of half drowning her trusting companions, was, on that never-to-be-forgotten day, as they say in books, to cover herself with glory—instead of mud.

The inhabitants of Pete's Patch rose to find the sun shining, the wind gone, the lake settled back in its proper place.

"The sea began to subside before I turned in last night," said Mr. Black. "It's as gentle as a lamb to-day."

"Look at the shore!" cried Marjory. "It's different. The beach that was sandy before the storm is all pebbly now; and down there where the cobblestones were it's all beautiful, smooth sand."

"And look," supplemented Jean, "at the mouth of that surprising river. It's a lot wider than it was when we came."

"Some time to-day," said Mr. Black, "I want to go to the little cove about halfway between here and Barclay's Point. That seems to be the spot that catches everything that is cast up by the sea. I need some thin boards for your cupboard, Sarah. I noticed the other day that the sharp cleft in the rocks back of that cove was filled with boards."

"That's an awfully interesting spot," said Jean. "If sailors threw bottles overboard with letters in them, that's where you'd find them—everything washes in at that spot."

"Or," said Henrietta, "if the captain lashed his only daughter to the mast and threw her overboard, that's where she'd land."

"Oh, I hope not," breathed tender-hearted Bettie.

"So do I," laughed Henrietta, with an impish glance at Mr. Black. "Think of being wrecked on the reef of Pete's Patch!"

"Norman's Woe certainly sounds better," agreed Mr. Black, "but let us hope that no one got wrecked any place. Now I must take a look at the Whale—I'm wondering how she weathered the storm."

"It's my turn to wash dishes," announced Jean.

"And mine to wipe," said Henrietta.

"Then Bettie and I will do the beds," said Marjory, quickly.

Mabel, left out in the cold, scowled darkly for a moment. Then she sat up very stiffly indeed.

"I shall go all by myself and pick up two big baskets of driftwood," said she.

"To-morrow morning," offered sympathetic Jean, "you're invited to do dishes with me, Mabel."

"And beds with me," added impish Henrietta.

"And to wash potatoes with me," teased Marjory.

"Why not let me do all the work?" queried Mabel, huffily. "But I will do dishes with you, Jean. I know you meant to be polite."

Presently Mabel, with two of the big baskets that had come with the provisions, slid down the sand bank to the beach. It was certainly a fine morning. Within two minutes, sturdy Mabel had forgotten that the others were paired off and that she was the odd one.

"The sky is blue, blue, blue," sang Mabel, marching up the smooth, hard beach; "the water is blue, blue, blue with golden sparkles; and the air is warm enough and cool enough and clean, clean, cle—ow!"

A leisurely wave had crept in and made a playful dash for Mabel's heedless feet.

"You got me that time," beamed friendly Mabel. "I guess you wanted to remind me that I was out after wood. All right, Mr. Lake, I'll walk closer to the bank. My! What nice little blocks for our fire. I love to find things."

Soon both baskets were filled; but by this time Mabel was well out of sight of the camp, having passed two of the little rocky points that extended into the lake, north of Pete's Patch.

"I wish I had a hundred baskets to fill," sighed Mabel. "I guess I'll leave these right here and go a little farther; it's such a nice day and I love to go adventuring. Oh! I know what I'll do; I'll go to Barclay's Point after my sweater—I hope it hasn't blown away."

So Mabel, with a definite object in view, started at a brisker pace toward Barclay's. Presently she reached the cove mentioned by Mr. Black as a catch-all for floating timber. The water was deeper at this place and a strong current carried quantities of driftwood to this wide, bowl-shaped cove. In severe storms, some of it was tossed high among the rocks and gnarled roots in a ravine-like cleft at the back. Nearer the water, many great logs, partially embedded in the sand, caught and held the lighter material tossed in by the waves.

"Oh!" cried Mabel, "I wish I had a million baskets! I know what I'll do. I'll just toss a lot of those go-in-a-basket pieces into a big pile way up there where the waves can't get them."

Gathering up the edges of her skirt, sturdy Mabel filled it with the clean, if not particularly dry, bits of wood, worn satin-smooth and white by long buffetings against graveled shores.

"I'll throw them behind that log," decided Mabel, toiling inland with her heavy burden. "They'll be perfectly safe up there—My! But they're pretty heavy. I guess there's room back of that big log for a whole wag—wow! ow!"

Mabel's final syllable was a curious, startled sound. While not precisely a gasp, a shriek, or a shout, it was a queer combination of all three.

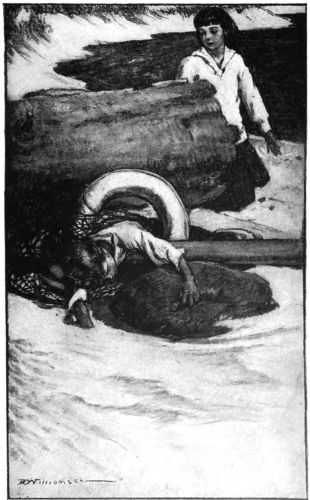

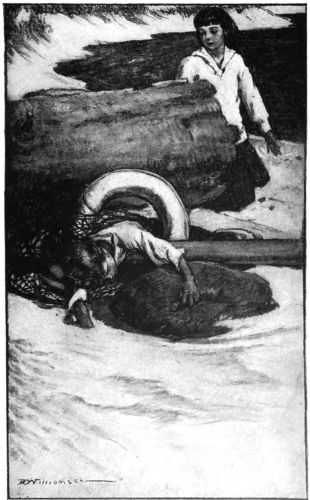

Mabel was startled, and with good reason. The space behind the log was already occupied; and by something that looked human.

The surprised little girl saw first a pair of water-soaked shoes attached to two very thin, boyish legs in black stockings. Beyond the stockings was a gray mass of tangled fish-net wound about something bulky and white that Mabel concluded was a life-preserver. Beyond that, an extended arm was partly buried in the sand. A thin, white hand was firmly closed over a sharply projecting point of rock. Very close against the huge log, so close as to be almost under it, was a shining, golden ball, the back of a boy's close-cropped head.

THE SPACE BEHIND THE LOG WAS ALREADY OCCUPIED

For a long moment Mabel, who had unconsciously dropped her load on her own toes, stood still and gazed questioningly at her unexpected find. Then the astonished little adventurer climbed over the wood she had dropped, bent down, and, with one finger, touched the boy's stocking, gingerly.

"If—if he'd been here very long," she said, sagely, "his stockings would have been faded. Things fade pretty fast on the lake shore. Perhaps if I poke him he'll wake up."

Mabel prodded the unfaded legs very gently with a pointed stick. There was no response.

"I guess he's dead," she sighed. "But I s'pose I ought to feel his pulse to find out for sure—ugh! I sort of hate to—suppose he is dead!"

But, bravely overcoming her distaste for this obvious duty, Mabel laid a trembling finger on the slim white hand. It was not as cold and clammy as she had feared to find it. Mabel touched it again, this time with several fingers. Yes, the hand was actually a little bit warm.

As she bent closer to the golden head, it seemed to Mabel that she could detect a sound of breathing, rather heavy breathing, Mabel thought; a little like Mrs. Crane's, when that good lady snored.

Mabel crouched patiently near the prostrate lad and listened. The labored breathing certainly came from that recumbent boy.

"But," argued Mabel, "if he's only taking a nap, why is he all tangled up in that net? And there's that life-preserver. He's been wrecked and tossed up, I believe. And he's still all wet underneath. Perhaps I ought to wake him up—he ought not to sleep in such wet clothes."

So Mabel grasped her discovery very firmly by one thin shoulder and shook him quite vigorously; but he still slept. Then, clutching him by both shoulders, she succeeded in dragging the heavy sleeper a few inches from the log; but he seemed rather too firmly anchored to his resting-place for this method to work successfully. Still, she had gained something, for now one ear and a bit of one cheek were visible. They were not white like the extended hand, but darkly red and very hot to the touch.

"Boy!" called Mabel. "Why don't you wake up? Don't you know that you're not drowned? Wake up, I say! Whoo! Whoo! Whoo!"

But the boy, in spite of what should have proved alarming sounds, made, as they were, in his very ear, still slumbered on in a strange, baffling fashion; and Mabel, after watching him in a puzzled way for several moments longer, found a broad shingle, which she balanced neatly on the boy's unconscious head.

"That'll keep the sun off," said she, "while I'm gone for help."