CHAPTER XXVII

A Visitor for Laddie

THE campers had barely finished breakfast when Captain Berry's launch chug-chugged into the little harbor; and the girls, still at the table, were laughing so heartily over one of Mr. Saunders' amusing tales that they had no suspicion of the launch's presence, at that unusual hour, until Mr. Black's hearty "Hi there, folks! Isn't anybody up?" made them all jump.

"Oh," breathed Mabel, evidently much relieved. "They didn't put him in prison, after all."

"I guess I'd better be getting into my own clothes," said Saunders. "I'll be going back with Captain Berry, I suppose. I'd much rather stay."

"There's no need for you to hurry," returned Mrs. Crane. "Captain Berry always stops for quite awhile; so finish your breakfast in peace."

Mr. Black, now plainly visible from the open door of the dining tent, was coming up the path from the beach. Behind him walked another person—a small woman in widow's garb. Her thin, white face wore an anxious, strained expression; her blue eyes beamed with eager expectancy, her hands twitched.

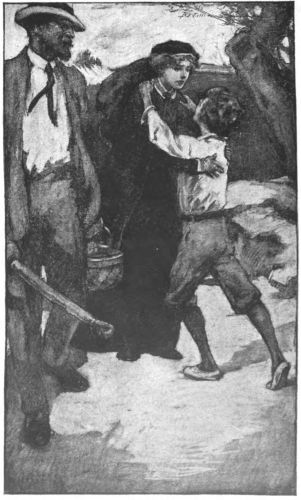

As the pair approached all the campers regarded them wonderingly. Suddenly Billy's cup dropped with a crash. In another moment he had leaped over the bench and was racing down the pathway.

"Mother!" he cried. "Mother! It's my mother!"

The little woman, laughing and crying together, was seized by this big whirlwind of a boy and hugged until she gasped for mercy.

"Oh, Laddie Lombard!" she cried. "I—I'm so glad—Oh, do let me cry just a minute! I thought—oh, Laddie!"

Saunders, with a delicacy that still further endeared him to the adoring girls, silently reached forth a long arm and dropped the tent flap. Mr. Black, his kindly face beaming with sympathy, pushed his way in; Laddie, rather close to tears himself, led his weeping mother to a bench under the trees.

"Her name," explained Mr. Black, seating himself at the breakfast table between Bettie and Jean, "is Mrs. Tracy Lombard. She wasn't in Pittsburg; but a friend of hers saw the notice in the paper and telegraphed her, and she came as fast as she could.”

"MOTHER!" HE CRIED. "MOTHER! IT'S MY MOTHER!"

"Of course she did," breathed Mrs. Crane. "But how did the boy——"

"Billy—Laddie, I mean—wasn't well this spring. It happened that he was coming down with typhoid; but his mother didn't know that—thought it was overwork in school. Hoping to benefit him by a change of climate, Mrs. Lombard, always rather fussy, I imagine, over this one precious infant, started West with him, over the Canadian Pacific route. She had relatives in Seattle or Portland—I've forgotten which. But that part of it doesn't matter.

"The second day after leaving Pittsburg, Laddie became so alarmingly ill that Mrs. Lombard was glad to accept the invitation of a fellow-traveler, a motherly, middle-aged woman, who lived in a small village on the north shore of Lake Superior."

"In Canada?" queried Marjory.

"Yes," returned Mr. Black. "In, as nearly as I could make out from Mrs. Lombard's description, a very quiet little place across the lake from Pete's Patch, if not exactly opposite. But so far away that one wouldn't expect small boats to make the journey. In that village, however, Laddie was seriously ill; because, by this time, he had pneumonia in addition to typhoid. For weeks he was a very sick boy. Then, when he began to mend, his mother found it difficult to hold him down, headstrong little rascal that he was, with no father to control him—his father died when Laddie was two years old, and I guess the boy has had his own way most of the time."

"He isn't a bit spoiled," defended Mrs. Crane. "But go on with your story."

"Long before he was well enough to walk he was begging to be taken on the water—he was always crazy about the water, his mother says; perhaps because most of his ancestors were sailors. On pleasant days—our spring was unusually mild, you remember—they allowed him to sit on the sunny veranda of Mrs. Brown's cottage, from which the lake, only two hundred feet distant, was plainly visible. At first they merely rolled him up in a blanket; but for the last three days of his sojourn in that place he had worn his clothes, shoes and all, since it galled his proud young spirit to be considered an invalid in the sight of the villagers.

"One day, during the half-hour or so that Mrs. Lombard was busy changing her dress, straightening her son's room, and so forth, Laddie disappeared."

"Before he could walk?" demanded Mrs. Crane.

"No, he was able to go from room to room by that time. You've noticed, haven't you, how quickly he recovers, once he is started? Well, as soon as he was better he disappeared."

"Where did he go?" asked Bettie. The girls, of course, were all nearly breathless with interest—no tale told by Saunders had held them so closely.

"Nobody knows," returned Mr. Black. "Probably nobody ever will know precisely what happened. However, there was a sociable half-breed fisherman, sort of a half-witted chap, who had leaned over the fence almost daily to talk to the boy. The theory is that he asked Laddie to go out in his boat. The landing was only a short distance away and almost directly in front of Mrs. Brown's house; but, owing to jutting rocks at the east side of the little bay, one could easily embark and very speedily get entirely out of sight of any of the houses. Now, the chances are that Laddie, or any other boy, invited by Indian Charlie to go out for a brief sail, would have considered it rather smart to accept the invitation. Would have thought it a good joke on his mother, perhaps—the best of boys make such mistakes, sometimes.

"Anyway, Laddie disappeared, and several days later Indian Charlie was found drowned near a rocky point several miles from the village; pieces of timber that might have been part of his boat were picked up after the storm—that same storm that brought Laddie to us. Moreover, another fisherman remembered noticing a boy with very bright hair in Charlie's boat, which he happened to pass that afternoon a mile or two down the shore. The wind was pretty fresh that day, and by night it was blowing a gale.

"Mrs. Lombard was forced to conclude, when no further word was heard of Laddie, that her boy had shared poor Charlie's fate—several far more seaworthy boats were wrecked that night and more than one unfortunate sailor lost his life. But Mrs. Lombard is now blaming herself for giving up hope so easily, though she did offer a reward, through the Canadian papers, for the finding of Laddie's body; and afterwards the Canadian shore was searched quite thoroughly. It didn't occur to anybody that Laddie, probably lashed to the mast by Indian Charlie, probably ill again and possibly delirious, as a result of exposure to wind and waves, could have been carried across Lake Superior in so frail a craft as that poor half-breed's boat. But the wind was in the right direction. How long the boat held together we shall never know.

"Mrs. Lombard learned afterwards that Indian Charlie was considered far too reckless in his handling of sailboats, and that he hadn't any better judgment than to take a sick boy out to sea if the boy showed the faintest inclination to go—and you know how wild that Billy-boy is about the water. Bless me, Sarah! That poor woman wouldn't wait for any breakfast——"

"I'll make some fresh coffee this minute," said Mrs. Crane, "but do save the rest of the story until I get back."

"There isn't any more," returned Mr. Black, taking a drink of water, "except that Mrs. Lombard reached town at four o'clock this morning, routed me out at half-past—the advertisement read 'apply to Peter Black'—and we came here as fast as gasoline could bring us."

"Then you didn't have any breakfast, either," guessed Mrs. Crane, shrewdly.

"I suspect I didn't," admitted Mr. Black.

And then Laddie Billy Blue-eyes, otherwise William Tracy Lombard, introduced his pretty little blond mother to all the campers.

"I'm remembering things so fast," said he, "that it makes me dizzy. Mother seems to be the missing link that connects me with Pittsburg and everything else. You know I always said that Dave reminded me of somebody? Well, when mother spoke of Indian Charlie, I knew. For a moment I could feel a boat heave up and down; and in a flash I saw a dark face something like Dave's, and some rather long, very black hair, also like Dave's. I could see the face two ways. Once it was laughing, over a fence top. Then it was all twisted up with fright—bending over me and scared blue. And while the face looked like that, there were hands fumbling about my waist——"

"As if," queried Bettie, "somebody were tying a life-preserver——"

"Yes, yes," declared Laddie. "And that dreadful face said things in a dreadful voice; but I couldn't hear—everything whirled and roared. Sometimes there was a horrible going-down feeling. Perhaps, after all, I just dreamed all that, but—but I think it happened."

"And you don't remember getting into any boat?" asked Mrs. Lombard.

"No, I don't," replied Laddie, whose always responsive eyes twinkled suddenly. "But if it were poor Charlie's fault, it wouldn't be polite to remember; if it were mine, I'd rather forget it; but I really don't remember one thing about those days in Canada, except that face like Dave's."

"No wonder," said Mrs. Lombard. "You were delirious when we took you off the train and so hazy when you were sitting up that you didn't know whether you were in Oregon or Pittsburg. You'd been terribly sick. The doctor said that your splendid constitution was all that saved you. And to think that you survived that storm——"

"Pooh!" scoffed Billy, "that boat probably lasted till I was tossed up on this shore. And anyhow, a bath does a fellow good. See how husky Mabel is—she's forever taking 'em. Say! That girl would fall into an ink bottle, if you left it uncorked—she just naturally tumbles into things."