CHAPTER V

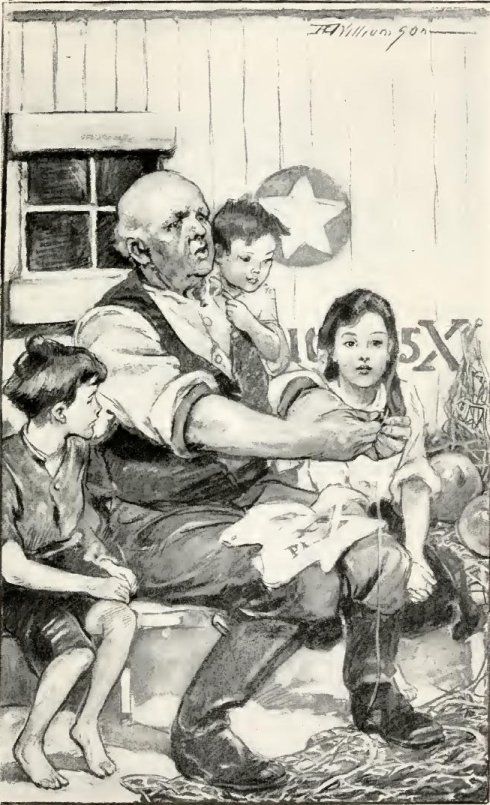

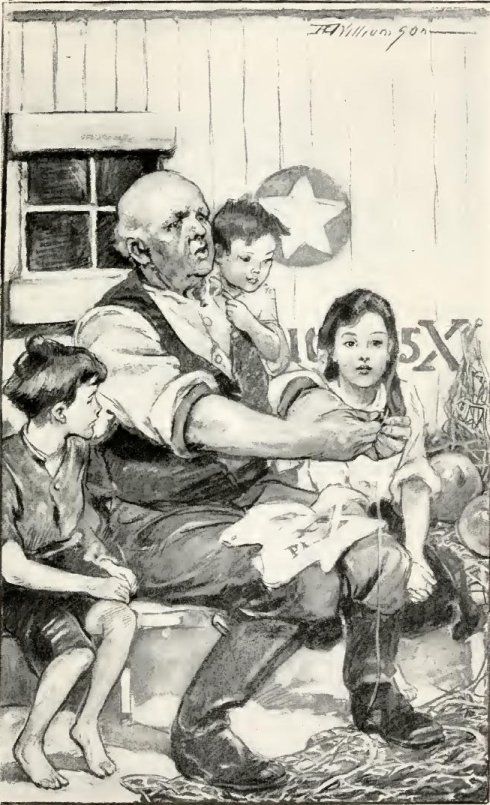

THE SEWING LESSON

Jeanne's father was out in the fishing boat with Barney; but Old Captain was mending a net near the door of his box-car. Perhaps he could help her with this new and perplexing problem. She would ask.

So, with her family trailing behind, she paid a visit to the Captain.

"Captain," said she, "can you mend anything besides nets?"

"Men's pants," returned Old Captain, briefly.

"Could you make anything? A shirt, you know, or—or an apron?"

"Well," replied the Captain, doubtfully, "I could sew up a seam, maybe, if somebody cut the darned thing—hum, ladies present—the old thing out."

"Could you teach me to sew a seam! You see, these children haven't a single clean thing to put on. If I could sew, I could make clothes for them, I believe, because I think Daddy would buy me some cloth."

"Well now, Jeannie, if you could manage to get the needle threaded—that there's what gets me. Hold on—I got a big one, somewhere's—now where did I put that needle!"

Old Captain rose ponderously to his feet, shuffled about inside his cabin and finally returned with a large spool of dingy thread, a mammoth thimble, and a huge darning needle. Also, he had found a piece of an old flour sack.

"Now, sit down aside me here and I'll show you. First you ties a knot—Oh, no! First you threads the needle like this—Well, by gum, went in, didn't she? An' then you ties the knot—a good big 'un so she won't slip out. Then you lays the edges of the cloth together, like this, and you pokes the needle through—Here you, Sammy! You'll get your nose pricked!”

THE SEWING LESSON

Inquisitive Sammy retired so hastily that he fell over backward.

"Now, you pull up the slack like this—Hey, Mike! I did get you—Say, boys, you sheer off a bit while this here's goin' on. I'm plum' dangerous with this here tool."

"What do you do with the thimble?" asked Jeanne, when she had removed placid Annie to a safe distance.

"Durned if I didn't forget that. You puts it on this here finger—no—well now, you puts it on some finger and uses it to push the needle like that."

"How do you keep it on?" asked Jeanne, twirling it rapidly on an upraised finger.

"I guess you'd better use the side of this here freight car like I allus does," admitted Old Captain. "Just push her in like that. Now, you try."

Jeanne sewed for a while, according to these instructions, then handed the result to her teacher. The Captain beamed as he examined the seam.

"Ain't that just plum' beautiful!" said he, showing it to Michael. "That little gal can sew. But I ain't just sure them is the right tools—this here seam in my shirt now—well, it ain't so goldarned—hum—hum—ladies present—so tarnation thick as that there what I taught ye."

At their worst, the good old Captain's mild oaths were never very bad. Unhappily Jeanne had heard far more terrifying ones from sailors on passing boats. As you see, Captain Blossom tried to use his very best language in the children's presence; but his best, perhaps, wasn't quite as polished as Léon Duval's.

"I don't see any large black knots in your shirt seam," observed Jeanne. "Mine look as if they'd scratch."

"Maybe they cuts 'em off," returned the Captain, eying the seam, doubtfully. "No, by gum! This here's done by machine. Yours is all right for hand work. But I tell ye what, Jeannie. You come round about this time tomorry and maybe, by then, I can find better needles. An' there was a sleeve I tore off an old shirt—maybe that'd sew better."

"I've always wondered," said Jeanne, "how people made buttonholes. They're such neat things. Can you make buttonholes?"

"To be sure I can. Nothin' easier. You cuts a round hole and then you takes half hitches all around it. I'm a leetle out of practice just now; but when I've practiced a bit—you see, you got to get started just right. But it's pretty soon to be thinkin' about the buttonholes."

"Do you makes the holes to fit the buttons or do you buy the buttons to fit the holes?"

"Well," replied the Captain, scratching his head, "mostly I makes the holes first like and then I fits the buttons to 'em. That's what I done on this here vest. You see, the natural ones was too small. Besides I lost the buttons, fust lick."

Interested Jeanne examined Old Captain's shabby waistcoat. There was a very large black button to fit a very large buttonhole. Next, a small white button with a buttonhole of corresponding size. Then a medium-sized very bright blue button with a hole to match that. The other two buttons were gone, but the store buttonholes remained.

"Three buttons—as long as they're big enough," explained Old Captain, "is enough to keep that there vest on. The rest is superfloo-us. Run along now, but mind you come tomorry and we'll have them other tools."

"I will," promised Jeanne.

"Me'll sew, too," promised Annie.

"Me, too," said Sammie.

"How about you, Mike?" laughed Old Captain.

"Aw, I wouldn't sew. That's girls' work."

The children had no sooner departed than Old Captain washed his hands and hurried into his coat. Feeling in his pocket to make sure that his money was there, he clambered up the steep bank, back of his queer house, to the road above. This was a pleasant road, because it curved obligingly to fit the shore line. The absence of a sidewalk did not distress Old Captain.

Half an hour later, Jeanne's friend, having reached the business section of the town, peered eagerly in at the shop windows. There seemed to be everything else in them except the articles that he wanted. Presently, choosing the shop that had the most windows, he started in, collided with a lady and a baby carriage and backed out again. He mopped his bald pink head several times with his faded red handkerchief before he felt sufficiently courageous to make a second attempt. Finally he got inside.

"Tarnation!" he breathed. "This ain't no place for a man—I'm the only one!"

A moment later, however, he caught sight of a male clerk and started for him almost on a run. He clutched him by the sleeve.

"Say," said Old Captain, "gimme a girl-sized thimble, a spool o' thread to fit, and a whole package o' needles."

"This young lady will attend to you," replied the man, heartlessly deserting him.

The smiling young lady was evidently waiting for her unusual customer to speak, so the Captain spoke.

"Will you kindly gimme a girl's-size needle, a spool o' thread, an' a package o' thimbles."

"What!" exclaimed the surprised clerk.

"A thimble, a needle, a thread!" shouted the desperate Captain.

"What size needles?"

"Why—about the size you'd use to sew a nice neat seam. Couldn't you mix up about a quarter's worth?"

"They come in assorted packets. What colored thread?"

"Why—make it about six colors—just pick 'em out to suit yourself."

"How about the thimble? Do you want it for yourself?"

"No, it's for a girl."

"About how big a girl?"

"Well, she's some bigger 'round than a whitefish," said the Captain, a bit doubtfully, "but not so much bigger than a good-sized lake-trout. Say, how much is them thimbles?"

"Five cents apiece."

"Gimme all the sizes you got. One of each. She might grow some, you know."

"Anything else?"

"Yep," returned Old Captain. "Suppose we match up them spools with some caliker—white with red spots, or blue, now. What do you say to that?"

"Right this way, sir," said the clerk, gladly turning her back in order to permit the suppressed giggles that were choking her, to escape.

The big Captain lumbered along in her wake, like a large scow towed by a small tug. He beamed in friendly fashion at the other customers; this dreaded shopping was proving less terrifying than he had feared. His pilot came to anchor near a table heaped with cheap print.

"We're having a sale on these goods," said she.

"What's the matter with 'em?" asked Old Captain, suspiciously.

"Why, nothing," replied the clerk. "They're all good. How much do you need? How many yards?"

"Well, just about three-quarters as much and a little over what it'd take for you. No need o' bein' stingy, an' we got to allow some for mistakes in cuttin' out."

"If you bought a pattern," advised the clerk, "there wouldn't be any waste."

"But," said Old Captain, earnestly, "she needs a waist and a skirt, too."

"I mean, you wouldn't waste any cloth. See, here's our pattern book."

Old Captain turned the pages, doubtfully. Suddenly his broad face broke into smiles.

"Well, I swan! Here she is. This is her—the girl them things is for. Same eyes, same hair, same shape—"

"But," queried the smiling clerk, "do you like the way that dress is made?"

"No, I don't," returned Captain Blossom. "It's got too many flub-dubs. I wouldn't know how to make them. You see, I'm a teachin' her to sew."

Finally, by dint of much questioning, the girl arrived at the size of the pattern required and the number of yards. Then Old Captain selected the goods.

"Gimme a bluer blue than that," he objected. "You got to allow a whole lot for to fade. Same way with the pink. Now that there purple's just right. And what's the matter with them red stripes? And that there white with big black spots. No, don't gimme no plain black—I'll keep that spool to mend with. Now, how about buttons? The young lady's had one lesson already on buttonholes."

"We're having a sale on those, too. Right this way. About how many?"

"About a pint, I guess," said Old Captain. "And for Pete's sake mix 'em up as to sizes so they'll fit all kinds of holes."

This time the clerk giggled outright.

"They're on cards," said she. "Here are three sizes of white pearl buttons—a dozen on each card. Five cents a card."

"Make it three cards of each size," returned the Captain, promptly. "She might lose a few. And not bein' flower seeds, they wouldn't sprout and grow more. Now, what's the damage for all that?"

The Captain's money smelled dreadfully fishy, like all the rest of his belongings; but the good old man didn't know that. He was greatly pleased with himself and with his purchases. But when he reached the open air, he paused on the doorstep to draw a deep breath.

"'Twould a taken less time to bought the riggin' fer a hull boat," said he, mopping his pink countenance. "But I made a rare good job of it."