My Uncle Toby's Apologetical Oration.

I am not insensible, brother Shandy, that when a man whose profession is arms, wishes, as I have done, for war,—it has an ill aspect to the world;—and that, how just and right soever his motives the intentions may be,—he stands in an uneasy posture in vindicating himself from private views in doing it.

For this cause, if a soldier is a prudent man, which he may be without being a jot the less brave, he will be sure not to utter his wish in the hearing of an enemy; for say what he will, an enemy will not believe him.—He will be cautious of doing it even to a friend,—lest he may suffer in his esteem:—But if his heart is overcharged, and a secret sigh for arms must have its vent, he will reserve it for the ear of a brother, who knows his character to the bottom, and what his true notions, dispositions, and principles of honour are: What, I hope, I have been in all these, brother Shandy, would be unbecoming in me to say:—much worse, I know, have I been than I ought,—and something worse, perhaps, than I think: But such as I am, you, my dear brother Shandy, who have sucked the same breasts with me,—and with whom I have been brought up from my cradle,—and from whose knowledge, from the first hours of our boyish pastimes, down to this, I have concealed no one action of my life, and scarce a thought in it—Such as I am, brother, you must by this time know me, with all my vices, and with all my weaknesses too, whether of my age, my temper, my passions, or my understanding.

Tell me then, my dear brother Shandy, upon which of them it is, that when I condemned the peace of Utrecht, and grieved the war was not carried on with vigour a little longer, you should think your brother did it upon unworthy views; or that in wishing for war, he should be bad enough to wish more of his fellow-creatures slain,—more slaves made, and more families driven from their peaceful habitations, merely for his own pleasure:—Tell me, brother Shandy, upon what one deed of mine do you ground it? (The devil a deed do I know of, dear Toby, but one for a hundred pounds, which I lent thee to carry on these cursed sieges.)

If, when I was a school-boy, I could not hear a drum beat, but my heart beat with it—was it my fault?—Did I plant the propensity there?—Did I sound the alarm within, or Nature?

When Guy, Earl of Warwick, and Parismus and Parismenus, and Valentine and Orson, and the Seven Champions of England, were handed around the school,—were they not all purchased with my own pocket-money? Was that selfish, brother Shandy? When we read over the siege of Troy, which lasted ten years and eight months,—though with such a train of artillery as we had at Namur, the town might have been carried in a week—was I not as much concerned for the destruction of the Greeks and Trojans as any boy of the whole school? Had I not three strokes of a ferula given me, two on my right hand, and one on my left, for calling Helena a bitch for it? Did any one of you shed more tears for Hector? And when king Priam came to the camp to beg his body, and returned weeping back to Troy without it,—you know, brother, I could not eat my dinner.—

—Did that bespeak me cruel? Or because, brother Shandy, my blood flew out into the camp, and my heart panted for war,—was it a proof it could not ache for the distresses of war too?

O brother! 'tis one thing for a soldier to gather laurels,—and 'tis another to scatter cypress.—(Who told thee, my dear Toby, that cypress was used by the antients on mournful occasions?)

—'Tis one thing, brother Shandy, for a soldier to hazard his own life—to leap first down into the trench, where he is sure to be cut in pieces:—'Tis one thing, from public spirit and a thirst of glory, to enter the breach the first man,—to stand in the foremost rank, and march bravely on with drums and trumpets, and colours flying about his ears:—'Tis one thing, I say, brother Shandy, to do this,—and 'tis another thing to reflect on the miseries of war;—to view the desolations of whole countries, and consider the intolerable fatigues and hardships which the soldier himself, the instrument who works them, is forced (for sixpence a day, if he can get it) to undergo.

Need I be told, dear Yorick, as I was by you, in Le Fever's funeral sermon, That so soft and gentle a creature, born to love, to mercy, and kindness, as man is, was not shaped for this?—But why did you not add, Yorick,—if not by Nature—that he is so by Necessity?—For what is war? what is it, Yorick, when fought as ours has been, upon principles of liberty, and upon principles of honour—what is it, but the getting together of quiet and harmless people, with their swords in their hands, to keep the ambitious and the turbulent within bounds? And heaven is my witness, brother Shandy, that the pleasure I have taken in these things,—and that infinite delight, in particular, which has attended my sieges in my bowling-green, has arose within me, and I hope in the corporal too, from the consciousness we both had, that in carrying them on, we were answering the great ends of our creation.

Chapter 3.LXXVI.

I told the Christian reader—I say Christian—hoping he is one—and if he is not, I am sorry for it—and only beg he will consider the matter with himself, and not lay the blame entirely upon this book—

I told him, Sir—for in good truth, when a man is telling a story in the strange way I do mine, he is obliged continually to be going backwards and forwards to keep all tight together in the reader's fancy—which, for my own part, if I did not take heed to do more than at first, there is so much unfixed and equivocal matter starting up, with so many breaks and gaps in it,—and so little service do the stars afford, which, nevertheless, I hang up in some of the darkest passages, knowing that the world is apt to lose its way, with all the lights the sun itself at noon-day can give it—and now you see, I am lost myself—!

—But 'tis my father's fault; and whenever my brains come to be dissected, you will perceive, without spectacles, that he has left a large uneven thread, as you sometimes see in an unsaleable piece of cambrick, running along the whole length of the web, and so untowardly, you cannot so much as cut out a..., (here I hang up a couple of lights again)—or a fillet, or a thumb-stall, but it is seen or felt.—

Quanto id diligentias in liberis procreandis cavendum, sayeth Cardan. All which being considered, and that you see 'tis morally impracticable for me to wind this round to where I set out—

I begin the chapter over again.

Chapter 3.LXXVII.

I told the Christian reader in the beginning of the chapter which preceded my uncle Toby's apologetical oration,—though in a different trope from what I should make use of now, That the peace of Utrecht was within an ace of creating the same shyness betwixt my uncle Toby and his hobby-horse, as it did betwixt the queen and the rest of the confederating powers.

There is an indignant way in which a man sometimes dismounts his horse, which, as good as says to him, 'I'll go afoot, Sir, all the days of my life before I would ride a single mile upon your back again.' Now my uncle Toby could not be said to dismount his horse in this manner; for in strictness of language, he could not be said to dismount his horse at all—his horse rather flung him—and somewhat viciously, which made my uncle Toby take it ten times more unkindly. Let this matter be settled by state-jockies as they like.—It created, I say, a sort of shyness betwixt my uncle Toby and his hobby-horse.—He had no occasion for him from the month of March to November, which was the summer after the articles were signed, except it was now and then to take a short ride out, just to see that the fortifications and harbour of Dunkirk were demolished, according to stipulation.

The French were so backwards all that summer in setting about that affair, and Monsieur Tugghe, the deputy from the magistrates of Dunkirk, presented so many affecting petitions to the queen,—beseeching her majesty to cause only her thunderbolts to fall upon the martial works, which might have incurred her displeasure,—but to spare—to spare the mole, for the mole's sake; which, in its naked situation, could be no more than an object of pity—and the queen (who was but a woman) being of a pitiful disposition,—and her ministers also, they not wishing in their hearts to have the town dismantled, for these private reasons,...—...; so that the whole went heavily on with my uncle Toby; insomuch, that it was not within three full months, after he and the corporal had constructed the town, and put it in a condition to be destroyed, that the several commandants, commissaries, deputies, negociators, and intendants, would permit him to set about it.—Fatal interval of inactivity!

The corporal was for beginning the demolition, by making a breach in the ramparts, or main fortifications of the town—No,—that will never do, corporal, said my uncle Toby, for in going that way to work with the town, the English garrison will not be safe in it an hour; because if the French are treacherous—They are as treacherous as devils, an' please your honour, said the corporal—It gives me concern always when I hear it, Trim, said my uncle Toby;—for they don't want personal bravery; and if a breach is made in the ramparts, they may enter it, and make themselves masters of the place when they please:—Let them enter it, said the corporal, lifting up his pioneer's spade in both his hands, as if he was going to lay about him with it,—let them enter, an' please your honour, if they dare.—In cases like this, corporal, said my uncle Toby, slipping his right hand down to the middle of his cane, and holding it afterwards truncheon-wise with his fore-finger extended,—'tis no part of the consideration of a commandant, what the enemy dare,—or what they dare not do; he must act with prudence. We will begin with the outworks both towards the sea and the land, and particularly with fort Louis, the most distant of them all, and demolish it first,—and the rest, one by one, both on our right and left, as we retreat towards the town;—then we'll demolish the mole,—next fill up the harbour,—then retire into the citadel, and blow it up into the air: and having done that, corporal, we'll embark for England.—We are there, quoth the corporal, recollecting himself—Very true, said my uncle Toby—looking at the church.

Chapter 3.LXXVIII.

A delusive, delicious consultation or two of this kind, betwixt my uncle Toby and Trim, upon the demolition of Dunkirk,—for a moment rallied back the ideas of those pleasures, which were slipping from under him:—still—still all went on heavily—the magic left the mind the weaker—Stillness, with Silence at her back, entered the solitary parlour, and drew their gauzy mantle over my uncle Toby's head;—and Listlessness, with her lax fibre and undirected eye, sat quietly down beside him in his arm-chair.—No longer Amberg and Rhinberg, and Limbourg, and Huy, and Bonn, in one year,—and the prospect of Landen, and Trerebach, and Drusen, and Dendermond, the next,—hurried on the blood:—No longer did saps, and mines, and blinds, and gabions, and palisadoes, keep out this fair enemy of man's repose:—No more could my uncle Toby, after passing the French lines, as he eat his egg at supper, from thence break into the heart of France,—cross over the Oyes, and with all Picardie open behind him, march up to the gates of Paris, and fall asleep with nothing but ideas of glory:—No more was he to dream, he had fixed the royal standard upon the tower of the Bastile, and awake with it streaming in his head.

—Softer visions,—gentler vibrations stole sweetly in upon his slumbers;—the trumpet of war fell out of his hands,—he took up the lute, sweet instrument! of all others the most delicate! the most difficult!—how wilt thou touch it, my dear uncle Toby?

Chapter 3.LXXIX.

Now, because I have once or twice said, in my inconsiderate way of talking, That I was confident the following memoirs of my uncle Toby's courtship of widow Wadman, whenever I got time to write them, would turn out one of the most complete systems, both of the elementary and practical part of love and love-making, that ever was addressed to the world—are you to imagine from thence, that I shall set out with a description of what love is? whether part God and part Devil, as Plotinus will have it—

—Or by a more critical equation, and supposing the whole of love to be as ten—to determine with Ficinus, 'How many parts of it—the one,—and how many the other;'—or whether it is all of it one great Devil, from head to tail, as Plato has taken upon him to pronounce; concerning which conceit of his, I shall not offer my opinion:—but my opinion of Plato is this; that he appears, from this instance, to have been a man of much the same temper and way of reasoning with doctor Baynyard, who being a great enemy to blisters, as imagining that half a dozen of 'em at once, would draw a man as surely to his grave, as a herse and six—rashly concluded, that the Devil himself was nothing in the world, but one great bouncing Cantharidis.—

I have nothing to say to people who allow themselves this monstrous liberty in arguing, but what Nazianzen cried out (that is, polemically) to Philagrius—

'(Greek)!' O rare! 'tis fine reasoning, Sir indeed!—'(Greek)' and most nobly do you aim at truth, when you philosophize about it in your moods and passions.

Nor is it to be imagined, for the same reason, I should stop to inquire, whether love is a disease,—or embroil myself with Rhasis and Dioscorides, whether the seat of it is in the brain or liver;—because this would lead me on, to an examination of the two very opposite manners, in which patients have been treated—the one, of Aoetius, who always begun with a cooling clyster of hempseed and bruised cucumbers;—and followed on with thin potations of water-lilies and purslane—to which he added a pinch of snuff, of the herb Hanea;—and where Aoetius durst venture it,—his topaz-ring.

—The other, that of Gordonius, who (in his cap. 15. de Amore) directs they should be thrashed, 'ad putorem usque,'—till they stink again.

These are disquisitions which my father, who had laid in a great stock of knowledge of this kind, will be very busy with in the progress of my uncle Toby's affairs: I must anticipate thus much, That from his theories of love, (with which, by the way, he contrived to crucify my uncle Toby's mind, almost as much as his amours themselves,)—he took a single step into practice;—and by means of a camphorated cerecloth, which he found means to impose upon the taylor for buckram, whilst he was making my uncle Toby a new pair of breeches, he produced Gordonius's effect upon my uncle Toby without the disgrace.

What changes this produced, will be read in its proper place: all that is needful to be added to the anecdote, is this—That whatever effect it had upon my uncle Toby,—it had a vile effect upon the house;—and if my uncle Toby had not smoaked it down as he did, it might have had a vile effect upon my father too.

Chapter 3.LXXX.

—'Twill come out of itself by and bye.—All I contend for is, that I am not obliged to set out with a definition of what love is; and so long as I can go on with my story intelligibly, with the help of the word itself, without any other idea to it, than what I have in common with the rest of the world, why should I differ from it a moment before the time?—When I can get on no further,—and find myself entangled on all sides of this mystic labyrinth,—my Opinion will then come in, in course,—and lead me out.

At present, I hope I shall be sufficiently understood, in telling the reader, my uncle Toby fell in love:

—Not that the phrase is at all to my liking: for to say a man is fallen in love,—or that he is deeply in love,—or up to the ears in love,—and sometimes even over head and ears in it,—carries an idiomatical kind of implication, that love is a thing below a man:—this is recurring again to Plato's opinion, which, with all his divinityship,—I hold to be damnable and heretical:—and so much for that.

Let love therefore be what it will,—my uncle Toby fell into it.

—And possibly, gentle reader, with such a temptation—so wouldst thou: For never did thy eyes behold, or thy concupiscence covet any thing in this world, more concupiscible than widow Wadman.

Chapter 3.LXXXI.

To conceive this right,—call for pen and ink—here's paper ready to your hand.—Sit down, Sir, paint her to your own mind—as like your mistress as you can—as unlike your wife as your conscience will let you—'tis all one to me—please but your own fancy in it.

(blank page)

—Was ever any thing in Nature so sweet!—so exquisite!

—Then, dear Sir, how could my uncle Toby resist it?

Thrice happy book! thou wilt have one page, at least, within thy covers, which Malice will not blacken, and which Ignorance cannot misrepresent.

Chapter 3.LXXXII.

As Susannah was informed by an express from Mrs. Bridget, of my uncle Toby's falling in love with her mistress fifteen days before it happened,—the contents of which express, Susannah communicated to my mother the next day,—it has just given me an opportunity of entering upon my uncle Toby's amours a fortnight before their existence.

I have an article of news to tell you, Mr. Shandy, quoth my mother, which will surprise you greatly.—

Now my father was then holding one of his second beds of justice, and was musing within himself about the hardships of matrimony, as my mother broke silence.—

'—My brother Toby,' quoth she, 'is going to be married to Mrs. Wadman.'

—Then he will never, quoth my father, be able to lie diagonally in his bed again as long as he lives.

It was a consuming vexation to my father, that my mother never asked the meaning of a thing she did not understand.

—That she is not a woman of science, my father would say—is her misfortune—but she might ask a question.—

My mother never did.—In short, she went out of the world at last without knowing whether it turned round, or stood still.—My father had officiously told her above a thousand times which way it was,—but she always forgot.

For these reasons, a discourse seldom went on much further betwixt them, than a proposition,—a reply, and a rejoinder; at the end of which, it generally took breath for a few minutes (as in the affair of the breeches), and then went on again.

If he marries, 'twill be the worse for us,—quoth my mother.

Not a cherry-stone, said my father,—he may as well batter away his means upon that, as any thing else,

—To be sure, said my mother: so here ended the proposition—the reply,—and the rejoinder, I told you of.

It will be some amusement to him, too,—said my father.

A very great one, answered my mother, if he should have children.—

—Lord have mercy upon me,—said my father to himself—....

Chapter 3.LXXXIII.

I am now beginning to get fairly into my work; and by the help of a vegetable diet, with a few of the cold seeds, I make no doubt but I shall be able to go on with my uncle Toby's story, and my own, in a tolerable straight line. Now,

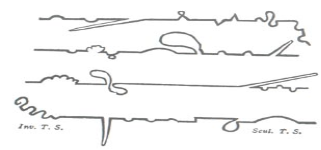

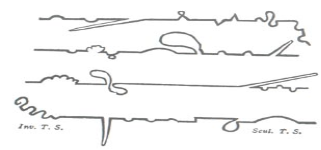

These were the four lines I moved in through my first, second, third, and fourth volumes (Alluding to the first edition.)—In the fifth volume I have been very good,—the precise line I have described in it being this:

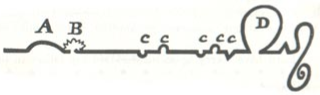

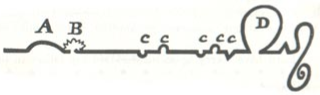

By which it appears, that except at the curve, marked A. where I took a trip to Navarre,—and the indented curve B. which is the short airing when I was there with the Lady Baussiere and her page,—I have not taken the least frisk of a digression, till John de la Casse's devils led me the round you see marked D.—for as for C C C C C they are nothing but parentheses, and the common ins and outs incident to the lives of the greatest ministers of state; and when compared with what men have done,—or with my own transgressions at the letters ABD—they vanish into nothing.

In this last volume I have done better still—for from the end of Le Fever's episode, to the beginning of my uncle Toby's campaigns,—I have scarce stepped a yard out of my way.

If I mend at this rate, it is not impossible—by the good leave of his grace of Benevento's devils—but I may arrive hereafter at the excellency of going on even thus:

(straight line across the page)

which is a line drawn as straight as I could draw it, by a writing-master's ruler (borrowed for that purpose), turning neither to the right hand or to the left.

This right line,—the path-way for Christians to walk in! say divines—

—The emblem of moral rectitude! says Cicero—

—The best line! say cabbage planters—is the shortest line, says Archimedes, which can be drawn from one given point to another.—

I wish your ladyships would lay this matter to heart, in your next birth-day suits!

—What a journey!

Pray can you tell me,—that is, without anger, before I write my chapter upon straight lines—by what mistake—who told them so—or how it has come to pass, that your men of wit and genius have all along confounded this line, with the line of Gravitation?

Chapter 3.LXXXIV.

No—I think, I said, I would write two volumes every year, provided the vile cough which then tormented me, and which to this hour I dread worse than the devil, would but give me leave—and in another place—(but where, I can't recollect now) speaking of my book as a machine, and laying my pen and ruler down cross-wise upon the table, in order to gain the greater credit to it—I swore it should be kept a going at that rate these forty years, if it pleased but the fountain of life to bless me so long with health and good spirits.

Now as for my spirits, little have I to lay to their charge—nay so very little (unless the mounting me upon a long stick and playing the fool with me nineteen hours out of the twenty-four, be accusations) that on the contrary, I have much—much to thank 'em for: cheerily have ye made me tread the path of life with all the burthens of it (except its cares) upon my back; in no one moment of my existence, that I remember, have ye once deserted me, or tinged the objects which came in my way, either with sable, or with a sickly green; in dangers ye gilded my horizon with hope, and when Death himself knocked at my door—ye bad him come again; and in so gay a tone of careless indifference, did ye do it, that he doubted of his commission—

'—There must certainly be some mistake in this matter,' quoth he.

Now there is nothing in this world I abominate worse, than to be interrupted in a story—and I was that moment telling Eugenius a most tawdry one in my way, of a nun who fancied herself a shell-fish, and of a monk damn'd for eating a muscle, and was shewing him the grounds and justice of the procedure—

'—Did ever so grave a personage get into so vile a scrape?' quoth Death. Thou hast had a narrow escape, Tristram, said Eugenius, taking hold of my hand as I finished my story—

But there is no living, Eugenius, replied I, at this rate; for as this son of a whore has found out my lodgings—

—You call him rightly, said Eugenius,—for by sin, we are told, he enter'd the world—I care not which way he enter'd, quoth I, provided he be not in such a hurry to take me out with him—for I have forty volumes to write, and forty thousand things to say and do which no body in the world will say and do for me, except thyself; and as thou seest he has got me by the throat (for Eugenius could scarce hear me speak across the table), and that I am no match for him in the open field, had I not better, whilst these few scatter'd spirits remain, and these two spider legs of mine (holding one of them up to him) are able to support me—had I not better, Eugenius, fly for my life? 'Tis my advice, my dear Tristram, said Eugenius—Then by heaven! I will lead him a dance he little thinks of—for I will gallop, quoth I, without looking once behind me, to the banks of the Garonne; and if I hear him clattering at my heels—I'll scamper away to mount Vesuvius—from thence to Joppa, and from Joppa to the world's end; where, if he follows me, I pray God he may break his neck—

—He runs more risk there, said Eugenius, than thou.

Eugenius's wit and affection brought blood into the cheek from whence it had been some months banish'd—'twas a vile moment to bid adieu in; he led me to my chaise—Allons! said I; the post-boy gave a crack with his whip—off I went like a cannon, and in half a dozen bounds got into Dover.

Chapter 3.LXXXV.

Now hang it! quoth I, as I look'd towards the French coast—a man should know something of his own country too, before he goes abroad—and I never gave a peep into Rochester church, or took notice of the dock of Chatham, or visited St. Thomas at Canterbury, though they all three laid in my way—

—But mine, indeed, is a particular case—

So without arguing the matter further with Thomas o'Becket, or any one else—I skip'd into the boat, and in five minutes we got under sail, and scudded away like the wind.

Pray, captain, quoth I, as I was going down into the cabin, is a man never overtaken by Death in this passage?

Why, there is not time for a man to be sick in it, replied he—What a cursed lyar! for I am sick as a horse, quoth I, already—what a brain!—upside down!—hey-day! the cells are broke loose one into another, and the blood, and the lymph, and the nervous juices, with the fix'd and volatile salts, are all jumbled into one mass—good G..! every thing turns round in it like a thousand whirlpools—I'd give a shilling to know if I shan't write the clearer for it—

Sick! sick! sick! sick—!

—When shall we get to land? captain—they have hearts like stones—O I am deadly sick!—reach me that thing, boy—'tis the most discomfiting sickness—I wish I was at the bottom—Madam! how is it with you? Undone! undone! un...—O! undone! sir—What the first time?—No, 'tis the second, third, sixth, tenth time, sir,—hey-day!—what a trampling over head!—hollo! cabin boy! what's the matter?

The wind chopp'd about! s'Death—then I shall meet him full in the face.

What luck!—'tis chopp'd about again, master—O the devil chop it—

Captain, quoth she, for heaven's sake, let us get ashore.

Chapter 3.LXXXVI.

It is a great inconvenience to a man in a haste, that there are three distinct roads between Calais and Paris, in behalf of which there is so much to be said by the several deputies from the towns which lie along them, that half a day is easily lost in settling which you'll take.

First, the road by Lisle and Arras, which is the most about—but most interesting, and instructing.

The second, that by Amiens, which you may go, if you would see Chantilly—

And that by Beauvais, which you may go, if you will.

For this reason a great many chuse to go by Beauvais.

Chapter 3.LXXXVII.

'Now before I quit Calais,' a travel-writer would say, 'it would not be amiss to give some account of it.'—Now I think it very much amiss—that a man cannot go quietly through a town and let it alone, when it does not meddle with him, but that he must be turning about and drawing his pen at every kennel he crosses over, merely o' my conscience for the sake of drawing it; because, if we may judge from what has been wrote of these things, by all who have wrote and gallop'd—or who have gallop'd and wrote, which is a different way still; or who, for more expedition than the rest, have wrote galloping, which is the way I do at present—from the great Addison, who did it with his satchel of school books hanging at his a..., and galling his beast's crupper at every stroke—there is not a gallopper of us all who might not have gone on ambling quietly in his own ground (in case he had any), and have wrote all he had to write, dry-shod, as well as not.

For my own part, as heaven is my judge, and to which I shall ever make my last appeal—I know no more of Calais (except the little my barber told me of it as he was whetting his razor) than I do this moment of Grand Cairo; for it was dusky in the evening when I landed, and dark as pitch in the morning when I set out, and yet by merely knowing what is what, and by drawing this from that in one part of the town, and by spelling and putting this and that together in another—I would lay any travelling odds, that I this moment write a chapter upon Calais as long as my arm; and with so distinct and satisfactory a detail of every item, which is worth a stranger's curiosity in the town—that you would take me for the town-clerk of Calais itself—and where, sir, would be the wonder? was not Democritus, who laughed ten times more than I—town-clerk of Abdera? and was not (I forget his name) who had more discretion than us both, town-clerk of Ephesus?—it should be penn'd moreover, sir, with so much knowledge and good sense, and truth, and precision—

—Nay—if you don't believe me, you may read the chapter for your pains.

Chapter 3.LXXXVIII.