CHAPTER V. A SHORT ONE—SHOWING, AMONG OTHER MATTERS, HOW Mr. PICKWICK UNDERTOOK TO DRIVE, AND MR. WINKLE TO RIDE, AND HOW THEY BOTH DID IT

Bright and pleasant was the sky, balmy the air, and beautiful the appearance of every object around, as Mr. Pickwick leaned over the balustrades of Rochester Bridge, contemplating nature, and waiting for breakfast. The scene was indeed one which might well have charmed a far less reflective mind, than that to which it was presented.

On the left of the spectator lay the ruined wall, broken in many places, and in some, overhanging the narrow beach below in rude and heavy masses. Huge knots of seaweed hung upon the jagged and pointed stones, trembling in every breath of wind; and the green ivy clung mournfully round the dark and ruined battlements. Behind it rose the ancient castle, its towers roofless, and its massive walls crumbling away, but telling us proudly of its old might and strength, as when, seven hundred years ago, it rang with the clash of arms, or resounded with the noise of feasting and revelry. On either side, the banks of the Medway, covered with cornfields and pastures, with here and there a windmill, or a distant church, stretched away as far as the eye could see, presenting a rich and varied landscape, rendered more beautiful by the changing shadows which passed swiftly across it as the thin and half-formed clouds skimmed away in the light of the morning sun. The river, reflecting the clear blue of the sky, glistened and sparkled as it flowed noiselessly on; and the oars of the fishermen dipped into the water with a clear and liquid sound, as their heavy but picturesque boats glided slowly down the stream.

Mr. Pickwick was roused from the agreeable reverie into which he had been led by the objects before him, by a deep sigh, and a touch on his shoulder. He turned round: and the dismal man was at his side.

‘Contemplating the scene?’ inquired the dismal man.

‘I was,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘And congratulating yourself on being up so soon?’

Mr. Pickwick nodded assent.

‘Ah! people need to rise early, to see the sun in all his splendour, for his brightness seldom lasts the day through. The morning of day and the morning of life are but too much alike.’

‘You speak truly, sir,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘How common the saying,’ continued the dismal man, ‘“The morning’s too fine to last.” How well might it be applied to our everyday existence. God! what would I forfeit to have the days of my childhood restored, or to be able to forget them for ever!’

‘You have seen much trouble, sir,’ said Mr. Pickwick compassionately.

‘I have,’ said the dismal man hurriedly; ‘I have. More than those who see me now would believe possible.’ He paused for an instant, and then said abruptly—

‘Did it ever strike you, on such a morning as this, that drowning would be happiness and peace?’

‘God bless me, no!’ replied Mr. Pickwick, edging a little from the balustrade, as the possibility of the dismal man’s tipping him over, by way of experiment, occurred to him rather forcibly.

‘I have thought so, often,’ said the dismal man, without noticing the action. ‘The calm, cool water seems to me to murmur an invitation to repose and rest. A bound, a splash, a brief struggle; there is an eddy for an instant, it gradually subsides into a gentle ripple; the waters have closed above your head, and the world has closed upon your miseries and misfortunes for ever.’ The sunken eye of the dismal man flashed brightly as he spoke, but the momentary excitement quickly subsided; and he turned calmly away, as he said—

‘There—enough of that. I wish to see you on another subject. You invited me to read that paper, the night before last, and listened attentively while I did so.’

‘I did,’ replied Mr. Pickwick; ‘and I certainly thought—’

‘I asked for no opinion,’ said the dismal man, interrupting him, ‘and I want none. You are travelling for amusement and instruction. Suppose I forward you a curious manuscript—observe, not curious because wild or improbable, but curious as a leaf from the romance of real life—would you communicate it to the club, of which you have spoken so frequently?’

‘Certainly,’ replied Mr. Pickwick, ‘if you wished it; and it would be entered on their transactions.’

‘You shall have it,’ replied the dismal man. ‘Your address;’ and, Mr. Pickwick having communicated their probable route, the dismal man carefully noted it down in a greasy pocket-book, and, resisting Mr. Pickwick’s pressing invitation to breakfast, left that gentleman at his inn, and walked slowly away.

Mr. Pickwick found that his three companions had risen, and were waiting his arrival to commence breakfast, which was ready laid in tempting display. They sat down to the meal; and broiled ham, eggs, tea, coffee and sundries, began to disappear with a rapidity which at once bore testimony to the excellence of the fare, and the appetites of its consumers.

‘Now, about Manor Farm,’ said Mr. Pickwick. ‘How shall we go?’

‘We had better consult the waiter, perhaps,’ said Mr. Tupman; and the waiter was summoned accordingly.

‘Dingley Dell, gentlemen—fifteen miles, gentlemen—cross road—post-chaise, sir?’

‘Post-chaise won’t hold more than two,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘True, sir—beg your pardon, sir.—Very nice four-wheel chaise, sir—seat for two behind—one in front for the gentleman that drives—oh! beg your pardon, sir—that’ll only hold three.’

‘What’s to be done?’ said Mr. Snodgrass.

‘Perhaps one of the gentlemen would like to ride, sir?’ suggested the waiter, looking towards Mr. Winkle; ‘very good saddle-horses, sir—any of Mr. Wardle’s men coming to Rochester, bring ‘em back, Sir.’

‘The very thing,’ said Mr. Pickwick. ‘Winkle, will you go on horseback?’

Now Mr. Winkle did entertain considerable misgivings in the very lowest recesses of his own heart, relative to his equestrian skill; but, as he would not have them even suspected, on any account, he at once replied with great hardihood, ‘Certainly. I should enjoy it of all things.’

Mr. Winkle had rushed upon his fate; there was no resource.

‘Let them be at the door by eleven,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Very well, sir,’ replied the waiter.

The waiter retired; the breakfast concluded; and the travellers ascended to their respective bedrooms, to prepare a change of clothing, to take with them on their approaching expedition.

Mr. Pickwick had made his preliminary arrangements, and was looking over the coffee-room blinds at the passengers in the street, when the waiter entered, and announced that the chaise was ready—an announcement which the vehicle itself confirmed, by forthwith appearing before the coffee-room blinds aforesaid.

It was a curious little green box on four wheels, with a low place like a wine-bin for two behind, and an elevated perch for one in front, drawn by an immense brown horse, displaying great symmetry of bone. An hostler stood near, holding by the bridle another immense horse—apparently a near relative of the animal in the chaise—ready saddled for Mr. Winkle.

‘Bless my soul!’ said Mr. Pickwick, as they stood upon the pavement while the coats were being put in. ‘Bless my soul! who’s to drive? I never thought of that.’

‘Oh! you, of course,’ said Mr. Tupman.

‘Of course,’ said Mr. Snodgrass.

‘I!’ exclaimed Mr. Pickwick.

‘Not the slightest fear, Sir,’ interposed the hostler. ‘Warrant him quiet, Sir; a hinfant in arms might drive him.’

‘He don’t shy, does he?’ inquired Mr. Pickwick.

‘Shy, sir?-he wouldn’t shy if he was to meet a vagin-load of monkeys with their tails burned off.’

The last recommendation was indisputable. Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass got into the bin; Mr. Pickwick ascended to his perch, and deposited his feet on a floor-clothed shelf, erected beneath it for that purpose.

‘Now, shiny Villiam,’ said the hostler to the deputy hostler, ‘give the gen’lm’n the ribbons.’

Shiny Villiam’—so called, probably, from his sleek hair and oily countenance—placed the reins in Mr. Pickwick’s left hand; and the upper hostler thrust a whip into his right.

‘Wo-o!’ cried Mr. Pickwick, as the tall quadruped evinced a decided inclination to back into the coffee-room window.

‘Wo-o!’ echoed Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass, from the bin.

‘Only his playfulness, gen’lm’n,’ said the head hostler encouragingly; ‘jist kitch hold on him, Villiam.’ The deputy restrained the animal’s impetuosity, and the principal ran to assist Mr. Winkle in mounting.

‘T’other side, sir, if you please.’

‘Blowed if the gen’lm’n worn’t a-gettin’ up on the wrong side,’ whispered a grinning post-boy to the inexpressibly gratified waiter.

Mr. Winkle, thus instructed, climbed into his saddle, with about as much difficulty as he would have experienced in getting up the side of a first-rate man-of-war.

‘All right?’ inquired Mr. Pickwick, with an inward presentiment that it was all wrong.

‘All right,’ replied Mr. Winkle faintly.

‘Let ‘em go,’ cried the hostler.—‘Hold him in, sir;’ and away went the chaise, and the saddle-horse, with Mr. Pickwick on the box of the one, and Mr. Winkle on the back of the other, to the delight and gratification of the whole inn-yard.

‘What makes him go sideways?’ said Mr. Snodgrass in the bin, to Mr. Winkle in the saddle.

‘I can’t imagine,’ replied Mr. Winkle. His horse was drifting up the street in the most mysterious manner—side first, with his head towards one side of the way, and his tail towards the other.

Mr. Pickwick had no leisure to observe either this or any other particular, the whole of his faculties being concentrated in the management of the animal attached to the chaise, who displayed various peculiarities, highly interesting to a bystander, but by no means equally amusing to any one seated behind him. Besides constantly jerking his head up, in a very unpleasant and uncomfortable manner, and tugging at the reins to an extent which rendered it a matter of great difficulty for Mr. Pickwick to hold them, he had a singular propensity for darting suddenly every now and then to the side of the road, then stopping short, and then rushing forward for some minutes, at a speed which it was wholly impossible to control.

‘What can he mean by this?’ said Mr. Snodgrass, when the horse had executed this manoeuvre for the twentieth time.

‘I don’t know,’ replied Mr. Tupman; ‘it looks very like shying, don’t it?’ Mr. Snodgrass was about to reply, when he was interrupted by a shout from Mr. Pickwick.

‘Woo!’ said that gentleman; ‘I have dropped my whip.’

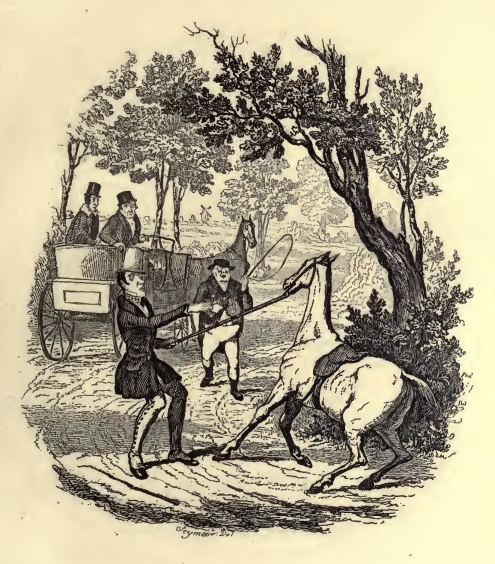

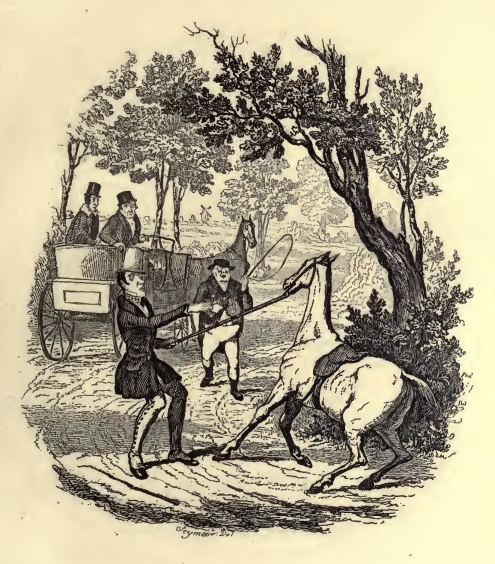

‘Winkle,’ said Mr. Snodgrass, as the equestrian came trotting up on the tall horse, with his hat over his ears, and shaking all over, as if he would shake to pieces, with the violence of the exercise, ‘pick up the whip, there’s a good fellow.’ Mr. Winkle pulled at the bridle of the tall horse till he was black in the face; and having at length succeeded in stopping him, dismounted, handed the whip to Mr. Pickwick, and grasping the reins, prepared to remount.

Now whether the tall horse, in the natural playfulness of his disposition, was desirous of having a little innocent recreation with Mr. Winkle, or whether it occurred to him that he could perform the journey as much to his own satisfaction without a rider as with one, are points upon which, of course, we can arrive at no definite and distinct conclusion. By whatever motives the animal was actuated, certain it is that Mr. Winkle had no sooner touched the reins, than he slipped them over his head, and darted backwards to their full length.

‘Poor fellow,’ said Mr. Winkle soothingly—‘poor fellow—good old horse.’ The ‘poor fellow’ was proof against flattery; the more Mr. Winkle tried to get nearer him, the more he sidled away; and, notwithstanding all kinds of coaxing and wheedling, there were Mr. Winkle and the horse going round and round each other for ten minutes, at the end of which time each was at precisely the same distance from the other as when they first commenced—an unsatisfactory sort of thing under any circumstances, but particularly so in a lonely road, where no assistance can be procured.

‘What am I to do?’ shouted Mr. Winkle, after the dodging had been prolonged for a considerable time. ‘What am I to do? I can’t get on him.’

‘You had better lead him till we come to a turnpike,’ replied Mr. Pickwick from the chaise.

‘But he won’t come!’ roared Mr. Winkle. ‘Do come and hold him.’

Mr. Pickwick was the very personation of kindness and humanity: he threw the reins on the horse’s back, and having descended from his seat, carefully drew the chaise into the hedge, lest anything should come along the road, and stepped back to the assistance of his distressed companion, leaving Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass in the vehicle.

The horse no sooner beheld Mr. Pickwick advancing towards him with the chaise whip in his hand, than he exchanged the rotary motion in which he had previously indulged, for a retrograde movement of so very determined a character, that it at once drew Mr. Winkle, who was still at the end of the bridle, at a rather quicker rate than fast walking, in the direction from which they had just come. Mr. Pickwick ran to his assistance, but the faster Mr. Pickwick ran forward, the faster the horse ran backward. There was a great scraping of feet, and kicking up of the dust; and at last Mr. Winkle, his arms being nearly pulled out of their sockets, fairly let go his hold. The horse paused, stared, shook his head, turned round, and quietly trotted home to Rochester, leaving Mr. Winkle and Mr. Pickwick gazing on each other with countenances of blank dismay. A rattling noise at a little distance attracted their attention. They looked up.

‘Bless my soul!’ exclaimed the agonised Mr. Pickwick; ‘there’s the other horse running away!’

It was but too true. The animal was startled by the noise, and the reins were on his back. The results may be guessed. He tore off with the four-wheeled chaise behind him, and Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass in the four-wheeled chaise. The heat was a short one. Mr. Tupman threw himself into the hedge, Mr. Snodgrass followed his example, the horse dashed the four—wheeled chaise against a wooden bridge, separated the wheels from the body, and the bin from the perch; and finally stood stock still to gaze upon the ruin he had made.

The first care of the two unspilt friends was to extricate their unfortunate companions from their bed of quickset—a process which gave them the unspeakable satisfaction of discovering that they had sustained no injury, beyond sundry rents in their garments, and various lacerations from the brambles. The next thing to be done was to unharness the horse. This complicated process having been effected, the party walked slowly forward, leading the horse among them, and abandoning the chaise to its fate.

An hour’s walk brought the travellers to a little road-side public-house, with two elm-trees, a horse trough, and a signpost, in front; one or two deformed hay-ricks behind, a kitchen garden at the side, and rotten sheds and mouldering outhouses jumbled in strange confusion all about it. A red-headed man was working in the garden; and to him Mr. Pickwick called lustily, ‘Hollo there!’

The red-headed man raised his body, shaded his eyes with his hand, and stared, long and coolly, at Mr. Pickwick and his companions.

‘Hollo there!’ repeated Mr. Pickwick.

‘Hollo!’ was the red-headed man’s reply.

‘How far is it to Dingley Dell?’

‘Better er seven mile.’

‘Is it a good road?’

‘No, ‘tain’t.’ Having uttered this brief reply, and apparently satisfied himself with another scrutiny, the red-headed man resumed his work. ‘We want to put this horse up here,’ said Mr. Pickwick; ‘I suppose we can, can’t we?’

Want to put that ere horse up, do ee?’ repeated the red-headed man, leaning on his spade.

‘Of course,’ replied Mr. Pickwick, who had by this time advanced, horse in hand, to the garden rails.

‘Missus’—roared the man with the red head, emerging from the garden, and looking very hard at the horse—‘missus!’

A tall, bony woman—straight all the way down—in a coarse, blue pelisse, with the waist an inch or two below her arm-pits, responded to the call.

‘Can we put this horse up here, my good woman?’ said Mr. Tupman, advancing, and speaking in his most seductive tones. The woman looked very hard at the whole party; and the red-headed man whispered something in her ear.

‘No,’ replied the woman, after a little consideration, ‘I’m afeerd on it.’

‘Afraid!’ exclaimed Mr. Pickwick, ‘what’s the woman afraid of?’

‘It got us in trouble last time,’ said the woman, turning into the house; ‘I woan’t have nothin’ to say to ‘un.’

‘Most extraordinary thing I have ever met with in my life,’ said the astonished Mr. Pickwick.

‘I—I—really believe,’ whispered Mr. Winkle, as his friends gathered round him, ‘that they think we have come by this horse in some dishonest manner.’

‘What!’ exclaimed Mr. Pickwick, in a storm of indignation. Mr. Winkle modestly repeated his suggestion.

‘Hollo, you fellow,’ said the angry Mr. Pickwick, ‘do you think we stole the horse?’

‘I’m sure ye did,’ replied the red-headed man, with a grin which agitated his countenance from one auricular organ to the other. Saying which he turned into the house and banged the door after him.

‘It’s like a dream,’ ejaculated Mr. Pickwick, ‘a hideous dream. The idea of a man’s walking about all day with a dreadful horse that he can’t get rid of!’ The depressed Pickwickians turned moodily away, with the tall quadruped, for which they all felt the most unmitigated disgust, following slowly at their heels.

It was late in the afternoon when the four friends and their four-footed companion turned into the lane leading to Manor Farm; and even when they were so near their place of destination, the pleasure they would otherwise have experienced was materially damped as they reflected on the singularity of their appearance, and the absurdity of their situation. Torn clothes, lacerated faces, dusty shoes, exhausted looks, and, above all, the horse. Oh, how Mr. Pickwick cursed that horse: he had eyed the noble animal from time to time with looks expressive of hatred and revenge; more than once he had calculated the probable amount of the expense he would incur by cutting his throat; and now the temptation to destroy him, or to cast him loose upon the world, rushed upon his mind with tenfold force. He was roused from a meditation on these dire imaginings by the sudden appearance of two figures at a turn of the lane. It was Mr. Wardle, and his faithful attendant, the fat boy.

‘Why, where have you been?’ said the hospitable old gentleman; ‘I’ve been waiting for you all day. Well, you do look tired. What! Scratches! Not hurt, I hope—eh? Well, I am glad to hear that—very. So you’ve been spilt, eh? Never mind. Common accident in these parts. Joe—he’s asleep again!—Joe, take that horse from the gentlemen, and lead it into the stable.’

The fat boy sauntered heavily behind them with the animal; and the old gentleman, condoling with his guests in homely phrase on so much of the day’s adventures as they thought proper to communicate, led the way to the kitchen.

‘We’ll have you put to rights here,’ said the old gentleman, ‘and then I’ll introduce you to the people in the parlour. Emma, bring out the cherry brandy; now, Jane, a needle and thread here; towels and water, Mary. Come, girls, bustle about.’

Three or four buxom girls speedily dispersed in search of the different articles in requisition, while a couple of large-headed, circular-visaged males rose from their seats in the chimney-corner (for although it was a May evening their attachment to the wood fire appeared as cordial as if it were Christmas), and dived into some obscure recesses, from which they speedily produced a bottle of blacking, and some half-dozen brushes.

‘Bustle!’ said the old gentleman again, but the admonition was quite unnecessary, for one of the girls poured out the cherry brandy, and another brought in the towels, and one of the men suddenly seizing Mr. Pickwick by the leg, at imminent hazard of throwing him off his balance, brushed away at his boot till his corns were red-hot; while the other shampooed Mr. Winkle with a heavy clothes-brush, indulging, during the operation, in that hissing sound which hostlers are wont to produce when engaged in rubbing down a horse.

Mr. Snodgrass, having concluded his ablutions, took a survey of the room, while standing with his back to the fire, sipping his cherry brandy with heartfelt satisfaction. He describes it as a large apartment, with a red brick floor and a capacious chimney; the ceiling garnished with hams, sides of bacon, and ropes of onions. The walls were decorated with several hunting-whips, two or three bridles, a saddle, and an old rusty blunderbuss, with an inscription below it, intimating that it was ‘Loaded’—as it had been, on the same authority, for half a century at least. An old eight-day clock, of solemn and sedate demeanour, ticked gravely in one corner; and a silver watch, of equal antiquity, dangled from one of the many hooks which ornamented the dresser.

‘Ready?’ said the old gentleman inquiringly, when his guests had been washed, mended, brushed, and brandied.

‘Quite,’ replied Mr. Pickwick.

‘Come along, then;’ and the party having traversed several dark passages, and being joined by Mr. Tupman, who had lingered behind to snatch a kiss from Emma, for which he had been duly rewarded with sundry pushings and scratchings, arrived at the parlour door.

‘Welcome,’ said their hospitable host, throwing it open and stepping forward to announce them, ‘welcome, gentlemen, to Manor Farm.’