CHAPTER XXIX

IN THE HALL OF AUDIENCE

SOME three or four hours after the rioting in the market place, Pascal and Lucette, who had been hurried to the Castle from Babillon’s house, were led to the Great Hall of Audience and placed in the midst of the large crowd of townsfolk who had been taken prisoners by the troops.

They were all herded together in a space about mid-way down the southern side of the Great Hall, in a space set apart by strong barriers and guarded by a ring of soldiers. Two other companies of soldiers were present, each about fifty in number, and they were drawn up one on each side of the daïs at the eastern end, where stood the Governor’s seat of audience and judgment.

Nearly all the prisoners had been injured in the conflict, and carried some grim evidences of the strife. Those whose wounds were serious wore such blood-stained bandages, dressings and slings as they had been able to improvise; but for the most part the wounds were undressed, and the men appeared just as they had been taken, with hair and faces grimed with blood and dirt, and clothes torn and jagged by the soldiers’ weapons, making a gruesome sight, which moved Lucette alternately to shrinking repulsion and tender pity.

“There must have been terrible fighting,” she said to Pascal, for they knew nothing of what had passed, and had been told merely that they were to be tried immediately, with the rest of the prisoners, for their share in the day’s work. “I wonder what has happened.”

“We can find that out; I will question some of the men,” he replied. “But I would rather know what is going to happen.”

“I am afraid we shall find that out too quite as quickly as we wish;” and Lucette glanced nervously about her at the men who were guarding the prisoners. She gave a little shiver of fear as her eyes fell on the Governor’s seat, and speculated anxiously what the ceremonious and somewhat terrifying preparations boded to them all. From that her gaze passed to the soldiers gathered about the daïs, whom she scrutinized closely; and just as Pascal returned from questioning their fellow-prisoners, she uttered an exclamation of surprise and pleasure.

“Monsieur Pascal,” she whispered eagerly, “there is Captain Dubois.”

“Dubois? Where?”

“There, among the soldiers on the right of the Governor’s seat: thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth—yes, fifteenth in the second row, counting from the daïs to the right. I am sure it’s he. Do you see him?”

“See him? I see more than him. Every man in the ranks there is ours, and Bassot himself is in command. We shall see something before we are many hours older, or I am no Bourbon.”

“Where can Gabrielle be? And M. Gerard?”

“So far as I gather, he is a prisoner; but the men here know little. There has been a riot in the market place; and these are some of the rioters. They have been told only that they are to be tried now.”

“Then they cannot have reached Malincourt. Oh, I wonder what they will do to us,” cried Lucette.

“I know how I would punish you were I the judge.”

“I would trust you,” she smiled.

“You wouldn’t like the punishment any more than I like the results of your act.” His tone was half earnest half jest; and she looked up puzzled.

“What is my crime?”

“You have given us splendid help in many ways; but I’m sadly out if our last mischances are not to be traced to that habit of yours—of making fools of us men.”

“Sadly out! I’m sadly out if you did not say that with a rare spice of relish. Sadly, indeed! Is this one of M. Burgher’s curtain lectures?”

“If you were still Madame Burgher, it might be,” he laughed.

“But I’ve gone back to Lucette, thank you, monsieur.”

“Aye, the Lucette whom the officer at the gate recognized.”

She understood him then. “You don’t think——?” she said eagerly.

“What I don’t think is not of much account. But I do think that any man who has once been under fire from your dark eyes would not readily forget them. He had not forgotten them, and they set him thinking too.”

“Oh, how cruel you are! To blame me in this way.”

“Blame you? It is the fortune of things. But if you think there’s a lesson in the thing, that good fellow of yours, Denys St. Jean, mightn’t be sorry if you learnt it. A thing of that sort is pretty much like a forest fire: you can start it easily, but you never know what may be burnt or how far it may spread before it’s put out.”

“I ought to be grateful to you for first frightening and then lecturing me at a time like this,” cried Lucette angrily.

“My punishment to you would be to sentence you to stop it for the future. That’s all. And now I’ve said my say,” he answered; and then, with a reassuring laugh, added: “As for this, it will be nothing. Have no fear. We may have a farce of a trial and a sentence after this Tiger’s manner; but before he can do anything, the tables will be turned on him, and he is not unlikely to find himself where we are. Have no fear, and don’t be surprised at anything that happens.”

Lucette was silent for a while, her manner a mixture of vexation and regret.

“Shall I say I have learnt my lesson, monsieur?” she asked with a look half mocking, half serious. “Your words have hurt me.”

“I fear you’ve but a poor memory for lessons, Lucette.”

“Ah, you are unendurable! I don’t like this lecturer’s mood of yours.”

“Then it’s fortunate I don’t wear it often. You are too brave and true a girl at heart, Lucette,” he said earnestly, “not to make your good will worth having for any man. And now I’ll be serious no more.”

But Lucette looked serious then, and twice turned to him as if to say something; although in the end she shrugged her shoulders and remained silent.

“Something is going to happen now,” said Pascal after a minute, as a number of the Governor’s suite entered and ranged themselves near the daïs. Both were watching them when Lucette cried suddenly—

“There is Gabrielle. Oh, how sad and pale she looks!”

“She takes it all very seriously,” replied Pascal; and pushing through the prisoners, he forced a way for Lucette and himself to the front. Gabrielle saw, and hurried to speak to them, when one of the guards stopped her.

“You cannot speak to the prisoners, mademoiselle,” he said.

“Nonsense, fellow,” exclaimed Pascal angrily.

“Silence, prisoner.”

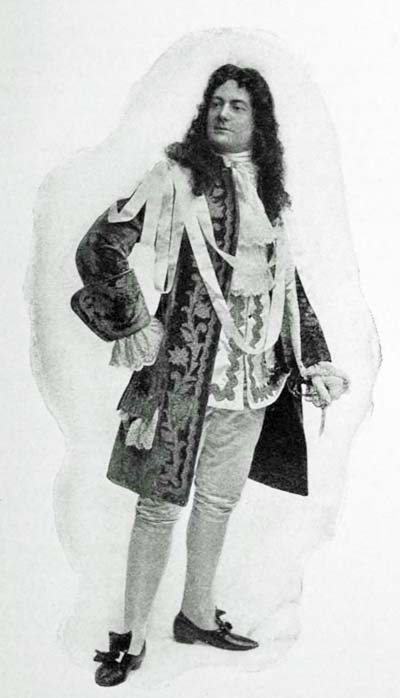

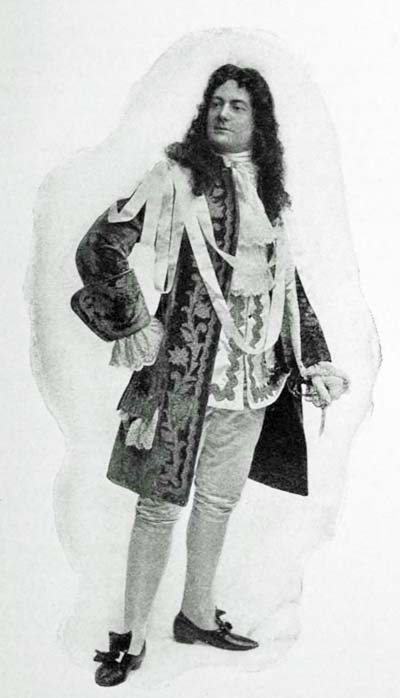

GERARD BORE HIMSELF WITH GREAT DIGNITY

“Not at your command, I promise you;” but Gabrielle making a hasty gesture to them, fell back, and at the moment there came a blast of trumpets heralding the approach, as they thought, of the Governor.

But to their amazement, it was Gerard, dressed in Bourbon uniform and preceded by two courtiers, who backed before him, bowing deeply as if in profound respect. One of them was d’Estelle, whose sallow sardonic face wore a smile of mockery; and as they entered, a herald called in loud tones—

“Place, there, place, for the most noble Lord Gerard de Bourbon.”

At the announcement the men about the Governor’s seat made a profound obeisance, and formed a lane to the steps leading to the daïs.

Gabrielle trembled, and showed such agitation and pain that Lucette was full of concern for her, while Pascal smiled and muttered to himself: “In the name of the devil, what can this mean?”

Gerard bore himself with great dignity, though understanding the thing little better than Pascal. He saw the smiles of derision which the Governor’s favourites exchanged one with another, but paid no heed to them, and acted as though the scene were no mockery, but earnest.

He was bowed to the Governor’s chair, and as he took his seat the Bourbon colours were suddenly unfurled, one on either side.

“His Grace the Duke de Rochelle entreats your lordship to be seated here, and will wait upon you to make his homage to your lordship as the representative of the illustrious Duke de Bourbon, the gracious Suzerain of Morvaix.” It was d’Estelle who said this, and his cynical smile was answered by the sneers of every courtier near.

“I shall be glad to receive his homage,” said Gerard as he stood by the Great Seat and looked about him. In his surprise he had not noticed Gabrielle when entering; but in a moment he saw her and went to her.

“What can this mockery portend, Gerard?” she asked nervously.

“Nay, I know not. The Governor seeks to amuse himself, I gather; but I care not so long as he does but waste enough time over it.”

“It has some sinister meaning.”

“So he will find, if he will but mock long enough,” he answered drily. “Meanwhile, we will play up to him in a way he will find little to his liking. Come. I will have a seat placed for you by my side.”

“No, no. Let us not anger him further,” she said, shrinking. “It is not prudent.”

“His anger is nothing to us. In an hour or two at most he will be on his knees to us, in no mocking mood, I promise you. Come;” and he took her hand, and leading her to the daïs he ordered d’Estelle to place a chair for her by him.

“I have no commands of the kind, most noble lord,” he sneered.

“I command here now. Do as I bid you,” answered Gerard sternly; and after a second’s hesitation it was done.

The moment after Gabrielle had taken her seat the soldier next Dubois let his musket drop, and at the clanging noise Gerard looked round and saw Dubois. It was a device to attract his attention to the fact that the whole of Bassot’s company were present.

Dubois, with a meaning glance, looked across to the prisoners, and Gerard, following the direction of his eyes, saw Pascal and Lucette. His face maintained its grave set expression; but his eyes were full of meaning as he met Pascal’s and glanced first at the prisoners and then at the men guarding them.

“We are well prepared, indeed, Gabrielle,” he whispered to her. “Dubois has conceived a plan daring even for him. Pascal is among the prisoners.”

“I have seen him, and Lucette too; but they would not let me speak to her.”

“It needs no speech. He understands. He will lead the prisoners when the moment comes, and they will overpower the men in charge of them.”

“But the soldiers here.”

“Are Bourbons to a man and Dubois is among them—eating out his heart, I will wager, for the moment when he can strike. Ah! here comes the Governor.”

“I have seen the Duchess, Gerard, and she is coming hither,” whispered Gabrielle quickly.

“Good; it will all help to waste time.”

The Governor, with de Proballe and others in attendance, entered then, and he gave a start of anger at seeing Gabrielle by Gerard’s side. He suppressed it quickly, however, and made his way with an affectation of respect toward Gerard. De Proballe, save for an occasional smirk, was preternaturally grave as he followed close to the Governor, bowing at every step with a grotesque, exaggerated obsequiousness that drew smiles from all.

Not an act or gesture of all this escaped Gerard, who saw through the childish contemptible burlesque by which it was designed to insult and humiliate him; but he continued to act precisely as he would have acted had the ceremony been genuine. He remained seated while the Governor approached the daïs and said, with a last low bow—

“I desire to offer my most humble greetings to my lord Gerard de Bourbon, and to bid you welcome to Morvaix.”

“Your recognition of my right and rank as the son of Morvaix’ Suzerain comes somewhat late, my lord Duke, and my previous reception at your hands was but an indifferent preface to this more fitting sequel. That preface yet remains to be explained.”

“I had not then convinced myself that you were indeed Great Bourbon’s son.”

“You are, then, now convinced?”

“Should I be here and you where you sit were it not so, most noble lord?”

“What, then, has convinced you? Your answer does not satisfy me.”

“That is a matter to be more conveniently discussed between us in private. All is well with our illustrious Suzerain?”

“My purpose in Morvaix is not concerned with the passing of mere idle compliments, and I bear no other greeting to your lordship than that you have already received and destroyed—an act you may now be anxious to explain.”

“Your noble lordship’s—condescension amazes me,” said the Governor, with a pause before the word, easy for all to understand. “You speak of a purpose. Will you be good enough to explain it?”

“I am indeed glad to do so to all present,” answered Gerard readily, rising. He welcomed the chance of letting the prisoners hear it. “My father, the Duke de Bourbon, the Suzerain of Morvaix, had heard ill reports of your government here: that your rule was harsh; that the people were oppressed by your soldiers; that justice was denied to the citizens, who were crushed and ruined by the imposition of iniquitous taxation; and further, that many dark and evil practices prevailed. He has sent me here, therefore, bearing full powers to inquire into the methods of your government and to redress the grievances of the suffering people.”

The Governor and those round him sneered and laughed; but the prisoners listened intently to every word, and not understanding that the scene was no more than burlesque, one of them cried in a loud voice—

“God save your lordship! Long live Bourbon!” and the cry was caught up by the whole body of prisoners and of Bourbon troops swelling into loud shouts, which, for the moment, the guards tried in vain to silence.

The Governor paled with anger.

“Your lordship knows how to appeal to the passions of such canaille,” he said, when silence had been partly restored.

“The passions have first been provoked by your misrule, my lord Duke,” answered Gerard in his stern ringing tone, to the delight of every one of the prisoners, who believed that justice was indeed at last to be meted out to the ruler they detested. Gerard observed the change in them, and saw, with intense satisfaction, that their mood was now such as would make them ready helpers in the scene to follow. “Who are these prisoners?” he asked the Governor.

“Their presence here is in accord with half my present purpose, most noble lord. I have deemed it best that they should be tried before you, illustrious Bourbon’s son, that you should know their crimes and yourself decree their punishment, you being, as I know you to be, the essence of justice and purity itself.”

At this de Proballe laughed audibly; and the sneer passed round the courtiers. It was he who had suggested to the Governor this mocking masquerade and the burlesque treatment of Gerard, and the irony of the scene delighted him.

But Gerard gave not a sign that he even saw the sneer.

“It was well arranged, my lord,” he said gravely. “And the other part in your purpose?”

“Is a personal affair, personal to the lady at your side and myself.” His look conveyed his meaning, and Gabrielle flinched.

“I think I know your meaning,” answered Gerard with unmoved composure, “and shall be glad to assist in furthering such a matter. But first, the prisoners. What is the charge and the evidence?”

De Proballe stepped forward here.

“Most noble and puissant lord Gerard of Bourbon,” he began with an insolent air, when Gerard interrupted him.

“Stay,” he said, with an imperious gesture. “I will not hear the Baron de Proballe. I know him to be incapable of telling the truth.”

De Proballe fell back at this insult, and in a voice vibrating with passion exclaimed—

“Will your lordship endure this insolence longer?”

But the Governor was rarely troubled when any one other than himself was humiliated. He was now, in truth, rather inclined to rejoice at de Proballe’s discomfiture, and replied with more than a dash of contempt—

“We must not forget, monsieur, that the lord Gerard comes from Paris with special knowledge we do not possess in Morvaix;” and the favourites round, taking their cue from this tone, sneered one to another with significant shrugs and glances.

“The evidence, my lord?” said Gerard with a show of impatience.

The Governor called up one of his officers then, who spoke of the affray in the market place; and Gerard, under cover of a desire to get at the truth, questioned him at considerable length, and so consumed much invaluable time. Two other officers followed, and some of the soldiers who had been injured by the crowd.

Having prolonged the matter as long as practicable, Gerald said—

“There is one point on which none of the witnesses have spoken. The provocation which drove the people to revolt? I would hear that.”

“There was none,” answered the Governor, who was now wearying of the farce. “And, moreover, these proceedings have lasted long enough.”

“We will, then, hear the prisoners themselves.”

“That is not the law in Morvaix,” was the curt reply. “They were caught red-handed, and can make no defence.”

“Is that your Morvaix justice, my lord? I am not surprised there is discontent, therefore. I will consider the matter I have heard, and give my judgment on the morrow. Meanwhile the prisoners will be released.”

They broke out into joyous shouts at this, and again the cries of “Long live Bourbon!” rent the air, to the intense mortification and anger of the Governor.

“This is too much,” he said with a scowl. “Your lordship will not be here on the morrow. I am sending you to-night on your way with an escort.”

But Gerard having his own end in view, affected not to hear him.

“And now the second matter you mentioned, my lord?” he asked; “affecting Mademoiselle de Malincourt here and yourself.”

“It is one that will doubtless please you,” answered the Governor. The burlesque so far had brought him far less pleasure than mortification; but he was now sure of his ground. He intended to make Gerard the medium of announcing his betrothal to Gabrielle, and the thought of this triumph of ingenuity appealed to him. “Mademoiselle de Malincourt has been pleased to consent to betroth herself to me, most noble lord; and your gracious presence makes this a fitting opportunity for the fact to be announced. You will be good enough to announce it.”

His tone was a threat, and as such Gerard understood it.

“Betrothal?” he repeated, with an excellent simulation of surprise, as if ignorant of the whole matter. “But is there not already one Duchess de Rochelle?”

“You know the facts well,” answered the Governor, dropping all form in his anger. “Do what I say, or there may be bitter reasons to regret it.”

But Gerard was a far better actor than he, and replied in a very loud tone, as if more surprised than ever—

“Do you wish me to announce to all present that, having already one wife, you propose to take a second? This is against the laws of France, my lord. I cannot make such an announcement.”

The Governor bit his lip and frowned, and said, in a threatening undertone—

“If you wish to leave Morvaix to-night with your head on your shoulders, you will announce it.”

“You are tearing off the mask, then, at last,” said Gerard, as calmly as before, with a smile.

“The Duchess herself has agreed to a divorce, so that this marriage may take place.”

“It is a union I cannot and will not sanction,” declared Gerard in a loud firm voice. “In the name of the Suzerain of Morvaix I forbid it. It must and shall not be.”

“We will see to that and have an end to this mockery,” cried the Governor, turning to give an order to his officers. But before he could deliver it an interruption came. The Duchess de Rochelle was borne into the hall on a litter.

Dead silence fell on all as her litter was set down at the foot of the steps.

“Here is the Duchess to speak for herself,” said Gerard.

She was pale and fragile, but her eyes were burning, and her soft voice thrilled all as she spoke.

“I have heard what has passed, my lord,” she said to Gerard; “and I have come here to protest against this contemplated wrong—the last of many I have endured at my husband’s hands. I will not have that innocent girl sacrificed. I protest solemnly against this infamy, in the name of God, the Holy Church, and of the laws of France.”

The effort seemed to exhaust her strength, and as she fell back faint and white, Gabrielle ran and knelt beside her.

Gerard paused for the Governor to speak, but rage deprived him of words.

“What say you now, my lord?” asked Gerard.

“This is a plot against me—a damnable scheme to try and put me to shame here,” cried the infuriated Governor. “You shall have an answer, never fear; and one little to your liking. Seize that man,” he cried to his officers, pointing to Gerard with a hand that shook with rage.

“Should not the hall be cleared?” said de Proballe, roused to great alarm for himself now at the fiasco of his plans.

The answer came from Gerard in a loud tone that resounded through the vast hall.

“No,” he cried; “not until the infamy of this thing has been made public.”

A profound hush of expectancy fell upon the great throng, each man holding his breath in wonderment and suspense; and before it was broken, an officer entered hurriedly and approached the Governor—

“My lord, my lord,” he said excitedly; “I crave your lordship’s pardon. Captain Boutelle has sent me to report that a large force of troops are approaching the city.”

“At last,” whispered Gerard under his breath, with a deep sigh of relief.

The Governor turned to two of his captains near him—

“Go at once, Des Moulins, and you, Courvoir, and see what this means. Close the gates against them, and hold them in parley till I come.”

The men hurried out in company with the officer who had brought the news.

“Clear the hall, Captain Fourtier; drive these canaille back to the prisons until I can deal with them.”

“Stop,” cried Gerard, springing to his feet. “No one leaves the hall except at my orders. The force you hear of is a Bourbon army coming here under my command. Your power is broken, my lord Duke. Who disobeys me now will answer to the Suzerain Duke, Great Bourbon, for his disobedience. Bear the Duchess away. Gabrielle, you had better leave with her.”

“By God, you shall rue this insolent presumption! Let the hall be cleared, I say. It is I, the Governor, who order it.”

The Great Hall became now the scene of intense excitement and commotion.

The guards commenced to obey the Governor’s command to drive the prisoners back to the cells. Groans and hooting broke out, and in the confusion Lucette contrived to slip past the soldiers and hasten to Gabrielle, and with her left by the side of the Duchess’ litter.

“Pascal, now,” called Gerard. “Captain Dubois, post your men at the doors, and see that no one enters.”

“To me, those who are for Bourbon,” shouted Pascal. “Down with the guards!” and he flung himself upon the soldier nearest to him, and wrenching his musket from him, began to use it vigorously. This was the signal for a fierce conflict between the prisoners and the guards; and in the meanwhile Dubois, sending half his men to guard the entrance to the hall, drew up the remainder as a bodyguard to protect Gerard, who had left the daïs and was now threatened by the officers and courtiers of the Governor.

The two bodies faced each other with fierce menacing looks: the Governor heading his courtiers, and Gerard his men, Dubois close at his side; while the din and clamour of the fight between prisoners and soldiers rendered it impossible for a word to be heard.

The struggle was not long. The prisoners outnumbered their opponents by three or four to one, and fought with the courage of men fighting for their freedom. They had Pascal to lead them, moreover; and he had clubbed his musket and laid about him with an energy and strength which none could resist wherever he went. And he was everywhere where the fight was thickest; and the stronger men, inspired by his example, seized the soldiers’ weapons and fought shoulder to shoulder with him with terrible effect.

The tables were soon turned, and the guards were beaten and overthrown or held prisoners by the men who a few minutes before had been cowering before them.

Before it ended, however, another struggle commenced. The Governor, mad with rage, called upon those with him, and drawing his sword, rushed at Gerard to cut him down, unarmed as he was. But Dubois had anticipated this, and his sword met that of the Duke, who sought with all his skill and trick of fence to break through the other’s guard.

The two were soon left fighting almost alone, for the Bourbon soldiers, maddened by the treacherous attempt upon Gerard’s life, attacked the courtiers with a right good will, and drove them back speedily to the wall with the fury of their onslaught. There they were speedily disarmed, but not until several of them had been wounded.

As the din of the conflict within the hall died down at the ignominious defeat of the Governor’s supporters, there came from outside the sound of heavy firing and the loud shouts of many men engaged in desperate fighting.

“It is d’Alembert; I hear the Bourbon cry,” shouted Pascal, hurrying to one of the entrances.

Gerard called to the Governor to yield; and Dubois, hearing this, changed his defensive tactics for those of vigorous attack, and as he was driving the Governor before him, he stepped back suddenly, and so brought the duel to an end.

“Now, my lord, you must see the uselessness of further resistance,” said Gerard. “You will give me your sword.”

“To a treacherous dog like you? Never!” was the fierce answer.

“Do you speak of treachery? I saved your life to-day in the market place, thinking that some spark of honour might remain to you to be roused by the act—and your reward was an order that I should be shot. And but now you sought to drive your sword into my heart, unarmed though I was. I will have no mercy for you: nothing but justice. Come, your sword. You are powerless.”

The Governor had a curse on his lips, but checked it, as a great shout came from Pascal and the Bourbons with him.

“The Castle is ours, my lord. D’Alembert is here,” cried Pascal; and the Bourbon soldiers came streaming into the hall, with d’Alembert at their head.

The Governor glanced round him with the look of a hunted beast, and then said sullenly—

“I have no option, it seems.” He held out his sword as if about to give it up; but, with a sudden change, he uttered a cry of rage, and lunged forward swiftly at Gerard’s heart.

Only just did the thrust miss as Gerard, fortunately suspicious, had noted the change of look and leapt aside.

With a curse at himself for his failure, the Governor sprang from the men who rushed up, and plunged the sword into his own heart.