CHAPTER VI.

MUSIC AND MUMMING.

It was December the twenty-third, and two o’clock in the afternoon. Frances and Austin had finished their early dinner at their mother’s luncheon-table, and were hurrying down the road to the school-house, where, by grace of the Rector, the Altruists’ entertainment was to be given.

“We still have plenty to do,” exclaimed Frances a little breathlessly, for the brother and sister were walking at a rapid pace. “The benches have to be arranged, and the tables laid, and I have one more wig to make for the ‘Ten Little Niggers’.”

“Gramercy!” exclaimed Austin; “did I not count ten heads, and ten wigs on the heads, at the dress rehearsal yesterday?”

“Teddy’s was not a proper wig,” sighed Frances. “You know Teddy has not a mother—or even an aunt, or a cousin, or an old nurse—to do anything of that sort for him. His father’s housekeeper is a horrid cross old thing, who would not have let Teddy act at all if she could have helped it. So I waylaid Mr. Bevers, and made him promise that Teddy should do anything I liked; and then Florry and I saw to his dresses between us. That is how Teddy comes to be a little nigger, and a baker-boy, and a fairy-page. He is such a darling, and he sings like a cherub. We wanted him ever so badly.”

“Girls always contrive to get what they want. They just peg away till they do. I will say, though, Frances, that they don’t mind going to any amount of trouble about it. Fancy making three dresses for one little shaver!”

“The baker-boy dress isn’t much—just a cap and apron,—and the little nigger was easy. The pink satin fairy-page was different, of course. Teddy and Gus, in pink and blue, look sweet.”

“They are rather fetching,” condescended Austin. “And Max’s idea of letting Teddy and Lilla sing the opening duet was a jolly good one. I’m not gone on babies, but Lilla’s a picture in that old-world thing her mother has dressed her up in.”

“She’s a picture as a fairy too,” said Frances; “though I think the minuet will be the most picturesque bit of the play. Florry is a lovely fairy god-mother, isn’t she? I do think she’s clever enough to act at the Lyceum!”

“The play’s the thing, undoubtedly, as Mr. Hamlet of Denmark remarked. Just wait till you see our Travesty, though. I flatter myself we’ll make Woodendites sit up. Max and I have worked out a splendid blood-curdling duel, with that drop-lunge Mr. Carlyon taught us for a finish. You didn’t see it at rehearsal yesterday?”

“No, I was called away; but I’m sure it will be capital. Max is funny, as Laertes. And Frank Temple is a fine King. How lucky it is he had that lovely dress of red velvet and ermine!”

“It is a real stage-dress. Frank had an uncle who went on the stage and became a famous actor. The regal robes belonged to him.”

“Fancy! That is interesting. I wonder what he would say if he knew they were going to be worn in the Hamlet Travesty.”

“He’d think it jolly cheek.”

“We never could have done the Travesty without Mr. Carlyon. Of course, it was his plan that we should act it; so I suppose that’s why he has been so much interested in it. And Miss Carlyon has stage-managed Florry’s play for us: she said it was her duty as president of the Altruists.—There’s Betty Turner, Austin. Make haste, and we’ll catch her up.”

The active pair soon caught up Betty, who was exceedingly plump, and was never seen in a hurry. She looked at her friends in mild amazement as they pelted down the hill and pulled up one on each side of her.

“How you two do excite yourselves!” she observed languidly. “Francy’s cheeks are as red as beet-root, and Austin will have no breath left for his song.”

“We shouldn’t enjoy anything if we didn’t get enthusiastic!” laughed Frances. “And isn’t this the great occasion—the Altruists’ field-day?”

“I shall have to leave the club, you make me so hot!” chuckled Betty. “I feel like building a snow-man when I look at you. At least, somebody else might build him for me, while I watched. The sensation would be equally cooling.”

“And not nearly so fatiguing,” said Austin. “Won’t you enjoy filling a hundred tea-cups twice over, Betty?”

“Catch me, indeed! I sha’n’t do the pouring out—that’s for May and Violet. They like it. Especially May. She has a genius for mathematics, and will be able to solve the problem of how many spoonfuls of tea to the pot, and how many pots to the tea-tableful of old women.”

“Give ’em plenty,” urged Austin. “Tibby Prout told me she hadn’t tasted tea this winter.”

“Tibby Prout!” repeated Betty meditatively. “I’ll keep my eye on Tibby: she shall have six cups. Just write her name here, Austin.” Betty pulled a notebook and pencil from her pocket. “It is so tiring to remember names.”

“You’ll have to remember to look in your notebook; and then you’ll have to remember why the name of Tibby Prout is written there; and then you’ll have to remember why I, and not you, have written it.”

“So I shall!” agreed Betty mournfully; and with an air of great depression she turned in at the school-house gate.

“‘A plump and pleasing person’,” whispered Austin mischievously in his sister’s ear. “It’s a good thing she’s amiable, as there’s so much of her!”

The boy ran off, laughing, to greet Max, who was just coming up to the gate. In his company came “Harry” the giant, a broad grin on his stolid face.

“See whom I’ve brought!” exclaimed Max, when greetings and confidences had passed between the chums. “You needn’t worry any longer about the benches, Frances. Harry has promised to arrange them all, just as you like.”

“That is kind of you, Harry,” said the girl, looking at the rustic with the frank kindliness which acted like a charm on her poorer neighbours, and made them her faithful allies. “I just wanted somebody very strong and rather patient. It will take a good while to move the benches, but it would have taken the boys twice as long as it will take you.”

“Never fear, Miss,” said the giant heartily; “I’ll turn this ’ere place upside-down in ’arf an hour, if so be as you want it.”

Then they all set busily to work. The school-house contained one large room, of which the upper part possessed a platform which was used for all sorts of village entertainments, such as penny-readings and magic-lantern shows. The young Altruist carpenters had rigged-up a plain screen of wood above and at the sides of the platform, and this, when hung with drapery, took the place of a proscenium, and was fitted with a curtain which would draw up and down. There were two entrances, right and left of the stage, and simple appliances to hold the simple scenery. Not much scope was given, perhaps, for elaborate effects; but Miss Carlyon as stage-manager, and Florry as dramatist, had used their wits, and some of their contrivances were wonderfully ingenious. They had availed themselves, too, of such opportunities as were offered by the command of a passage running from one stage-door to the other, outside the room. Here they marshalled their processions, and assembled their hidden choir, and even found room for one or two members of the orchestra when these were wanted to discourse music at moving moments of the performances.

Owing to the length of the programme, the proceedings were to begin at four o’clock, with a generous tea. Before the hour arrived the Carlyons made their appearance, and were immediately in the thick of everything. Edward, his long coat flying behind him, dashed hither and thither in response to agonized calls from boys in difficulties; while Muriel gave helping hands to her girls, until the preparations for tea were complete.

Every Altruist wore a crimson badge, and a similar one was presented to every guest on entrance. The stage-hangings were crimson; the Christmas greetings hung up on the walls were fashioned in crimson letters on a white ground. Of course the room was prettily decorated with green-stuffs and berries, and the long tables grouped in the background were ornamented with lovely flowers. Altogether, the aspect of the room was distinctly festive when, as the clock struck four, the doors were thrown open and the guests began to pour in. Men, women, and children—all had been invited; and for once the denizens of Lumber’s Yard mingled with the better-class cottagers. Bell Baker, still pale, and poorly-clad, was brought under the care of the Doctor himself, who had borrowed a bath-chair, and packed his suffering charge into it. With Bell came her three eldest children; the baby was being cared for by an enterprising cottage-woman, who had decided to stay at home from the Altruist Feast and “take in” babies at a penny the head! The resulting fortune in shillings was a satisfactory consolation to her for the loss of her treat.

The Altruist fund might have fallen short of the demands made on it for the expenses of the grand entertainment, had it not been amply supplemented by those well-to-do inhabitants of Woodend who were interested in the undertaking. The feasts proper—both tea and supper—were “entirely provided by voluntary contributions”, as Frances had proudly announced at the last meeting of the Society. The rector offered fifty pounds of beef; Miss Carlyon’s cookery-class made a score of plum-puddings and a hundred mince-pies, the materials coming from the kitchens of Altruists’ mothers; the oranges and apples and almonds and raisins, with such trifles as bon-bons and sweets, were sent in by various Altruists’ fathers. Mrs. Morland promised fifty pounds of cake, and as Austin was allowed to do the ordering it was as plummy as Christmas cake knows how to be. In this way gifts rapidly mounted up; and by the time it became necessary to reckon up the funds, Frances found that she had only sugar to provide!

This was very cheering to the young leader of the Altruists, who had dreaded having to check the bounding ambition of her associates. The sewing-meetings had done great things with scarlet flannel and crimson wool; but in this direction, also, the grown-ups were kind. Mrs. Morland, who had quietly assumed the headship of Woodend society, dropped polite hints at dinner-parties and distributed confidences at “At Homes”. It became generally understood that all contributions of new and useful clothing would be thankfully received in the club-room. Perhaps Mrs. Morland’s patronage did less for the cause than did the popularity of her daughter. Frances was everybody’s favourite; and the pleasure of receiving her earnest thanks, and seeing the joyful light in her grave gray eyes, sent many a Woodend matron and maid to the making of shirts.

The Carlyons had determined privately to run no risk of usurping the credit which belonged of right to the originators of the entertainment; and they kept very much behind the scenes during the evening, except when sharing the labours of the party told off to preserve order and see that all the guests were comfortably placed. Tea over, and the tables cleared, the orchestra struck up a lively medley of popular tunes, while the company were ranged on the benches that Harry had set in two rows, facing the stage, in the upper part of the long room. Behind these benches was a small space, and then a few rows of chairs for the families and friends of the Altruists, who were to be permitted to view the performances in consideration of their liberal help.

When all were seated, and quiet reigned in the neighbourhood of the empty tea-tables, the orchestra ceased to make melody, and Miss Carlyon, slipping round from the back, took her place before the piano, the fifteen-year-old Pianist of the band retiring modestly to a three-legged stool that she shared with the fourteen-year-old First Violin. The footlights were turned up, the gas in the auditorium was turned down; on the whole audience fell the hush of expectancy. Miss Carlyon played a few bars of a simple children’s song; then the curtain swayed backward a little to allow two performers to step before it.

“A STORY WE BRING YOU FROM FAËRY LAND.”

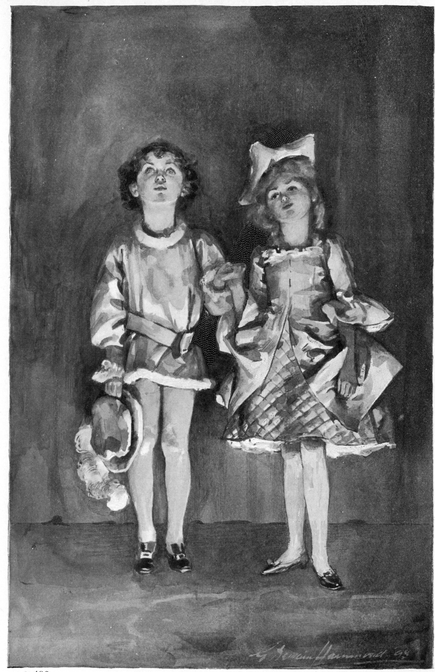

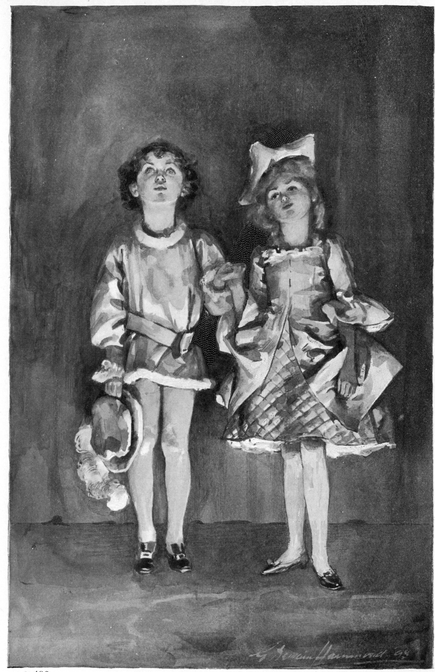

First came Teddy Bevers, beautiful to behold in his pink satin tunic trimmed with swansdown, lace ruffles, pink silk stockings, and buckled shoes. His dark curls bobbed merrily all over his little head, as, holding his pink hat with its white plume behind him, he bowed low to another small figure tripping after him. Lilla Turner was a tiny, slender maiden, just the opposite of plump Betty, her sister and slave; she wore a short petticoat of quilted white satin, and a Watteau bodice and panier of white and gold brocade. Lilla returned Teddy’s bow with a sweeping curtsey, then took his offered hand, and the little pair paced solemnly to the front and made a profound salute to the audience. Both sang prettily; and Miss Carlyon’s careful teaching had given them a clear enunciation, which made the words of their prologue audible throughout the room:

“A story we bring you from Faëry Land,

A story of gallant, and maiden, and sprite;

And we ask you to lend us a favouring hand,

While we tell it, and sing it, and act it to-night.

List, list to our story of maiden and fay,

Of prince, knight, and peasant; oh, listen, we pray!”

Teddy and Lilla continued, through three verses, to entreat the indulgence of an audience already disposed to be more than kind; then the salutes were sedately repeated, and the little couple vanished amid enraptured applause. The beauty and grace of the small actors had warmed the hearts of the workaday folk to whom they sang, and the Woodend villagers demanded an encore with all their hands and tongues.

The programme was long enough already; and, besides, Florry’s sense of dramatic fitness made her look on a repetition of her prologue as something like barbarism. So Teddy and Lilla were told to go on again and bow their acknowledgments; which they did, kissing their hands ere they finally retired.

They had paved the way admirably for the others, and the fairy play was throughout a brilliant success. The curtain was rung down on a most picturesque tableau, while Max burned red fire at the wings, and the orchestra discoursed sweet music. Three times the curtain was raised before the audience would be satisfied; and even then there were calls for the “author”, and Florry was pulled on to the stage by a group of enthusiastic little fairies.

A big sigh of satisfaction seemed to come from everybody; and the onlookers were still assuring each other that nothing could beat the fairy play, when the orchestra struck up a familiar melody. All the boys on the benches began to hum appreciatively; and the curtain slowly rose, while across the stage in a couple of bounds sprang the First Little Nigger. His age was twelve, his face and hands were sooty-black; he wore a costume of scarlet-and-white striped cotton jacket, green knickerbockers, one scarlet and one white stocking, a white collar of enormous proportions, and a lovely horse-hair wig. After him came his nine brothers, in similar raiment, and in gradations of size, which ended in Teddy Bevers, who informed his hearers that he was the “Tenth Little Nigger Boy!”

Mr. Carlyon had written a new version of the historic ditty—a version strictly topical, and full of harmless local allusions, which won peals of laughter from the benches. The actors had been taught some amusing by-play; and their antics drew shrieks of delight from small boys and girls, who had gaped in uncomprehending wonderment at the Fairy Godmother. It was of no use to try to refuse an encore for the Ten Little Niggers, so Mr. Carlyon sent them on again to repeat their fun and frolic for the benefit of the little ones in front.

The niggers had brought the younger portion of the audience into such an uproarious condition that the feelings of the First Violin were sadly tried by the hubbub amid which she stepped on to the platform. But now, if ever, Woodend was on its good behaviour; and, as the elders wanted to “hear the music”, they coaxed and scolded the juniors into a restless silence. However, the melting strains of Raff’s “Cavatina” were not beyond the appreciation of anybody; and those who did not admire her plaintive performance for its own sake, were full of wonder at the skill of the First Violin. The next item on the programme was a vocal duet by Frances and her brother. Austin sang well in a charmingly fresh treble, with which his sister’s alto blended very prettily; and the pair had practised most conscientiously. This was the only number of the programme in which Frances’s name appeared. The girl had declined to be put down for anything which would give her prominence, because she knew her mother would prefer to see Austin to the fore, and Frances had a delicate instinct which warned her not to court jealousy by claiming too much for the Morland family. Austin had played one of the best parts in the fairy piece, was to play Hamlet in some scenes selected by Mr. Carlyon from Poole’s “Travesty”, and besides his duet with Frances, had a solo to sing. Nobody grudged the bright, good-natured boy his many appearances, but Frances felt that they ought to suffice for both.

The concert swung gaily on its way. The First Little Nigger, still sooty of face and brilliant of attire, sang Hard times come again no more to his own banjo accompaniment, and was rewarded by the sight of many pocket-handkerchiefs surreptitiously drawn forth. There was a flute solo from Guy Gordon, a musician whose fancy usually hovered between the jew’s-harp and the concertina; but on this occasion he gave a “Romance” for his more classical instrument, and moved to emulation every rustic owner of a penny whistle. Three little lads, dressed as sailor-boys, were immensely popular in a nautical ditty, which cast a general defiance at everybody who might presume to dispute the sovereignty of The Mistress of the Sea; and three little girls with three little brooms joined in a Housemaid’s Complaint, which set forth in touching terms the sufferings of domestics who were compelled to be up by ten, and to dine on cold mutton and fried potatoes. Songs, humorous and pathetic, filled up the concert programme, until it terminated in a costume chorus, How to make a Cake.

This item was an exemplification of the picturesque possibilities of familiar things. A table in the middle of the stage was presided over by Betty, attired in print frock, cap, and apron. In front of her on the table stood a big basin. To her entered a train of boy and girl cooks, carrying aloft bags and plates containing materials for cake-making. A lively song, descriptive of the action, accompanied Betty’s demonstration of the results of her cookery studies; the cake was mixed, kneaded, disposed of in a tin, and proudly borne off to an imaginary stove by Guy Gordon, the biggest baker. The song continued, descriptive of the delightful anticipations of the cake-makers; and when Guy returned carrying a huge plum-cake, this was promptly cut into slices by Betty and distributed among her helpers, who, munching under difficulties, marched round the stage to a triumphant chorus of “We’ll show you how to eat it!”

Max was to appear as Laertes in the Travesty, and had hitherto taken no more distinguished part in the entertainment than the playing of what it pleased him to call “twentieth fiddle” in the orchestra. But he now found greatness thrust upon him. No sooner had the cooks acknowledged their call and vanished, than Harry the giant uprose in his place, and boldly addressed Mr. Carlyon.

“Axing parding, sir, if I may make so bold, there’s some of us ’ere—me and my mates—wot knows as ’ow the young Doc’ can sing a rare good song. And we takes the liberty of askin’ Master Max to favour us.”

Harry’s speech created an immediate sensation; but his sentiments were upheld by prolonged applause from his “mates” and the audience generally.

Edward Carlyon successfully maintained a strict impartiality in his dealings with his pupils; but in his heart of hearts he kept a special corner for Max Brenton. Well pleased with Harry’s request, he leant towards the “twentieth fiddle”, and said:

“You hear, Max? You’re honoured by a distinct invitation; so up with you to the platform and let’s hear what you can do!”

Max, covered with blushes, was pushed forward by the entire orchestra, while Carlyon seated himself in front of the piano.

“What shall it be, lad?—The Old Brigade, I think. Muriel, will you tell the boys and girls behind to provide Max with a chorus?”

Max plucked up courage, and obeyed. His slight figure, in its trim Eton suit, stood out bravely on the platform, reminding Harry and one or two others of another evening when the boy had sung “against time” to save a woman from suffering.

All the Altruists knew The Old Brigade, and had chimed in with a chorus many a time when the Carlyons’ young choristers had held their merry practices in the boys’ school-room. So the gallant song went with splendid spirit, and when it reached its last verse the chorus was reinforced by the greater number of the audience, who proceeded rapturously to encore themselves.

Max’s song was an excellent finish to the concert; and then the onlookers were allowed a few minutes to recover their breath and discuss the performance, while the stage was made ready for the Travesty.

In front reigned mirth, satisfaction, and pleasing hopes of more good things to come. Behind, the aspect of affairs had changed suddenly. At the end of Max’s song a letter was handed to Carlyon, whose face, as he read, became a proclamation of disaster. He was in the little room at the end of the passage, which had been made ready for the use of the performers when off the platform; and round him had gathered the boys and girls who were to figure in the Travesty.

“Bad news, youngsters,” said Carlyon dismally. “The first hitch in our evening’s entertainment. I wondered why Frank Temple was so late in arriving. This letter—which evidently ought to have reached me before—is to tell me that Mr. and Mrs. Temple have been summoned by telegram to Mr. Temple’s home, where his father is lying dangerously ill. The boy was named in the telegram—his grandfather had asked for him; so of course he has gone with his parents. Now,” continued Carlyon, looking at the blank faces before him, “I know that all of you will feel very much for Frank; but just at present we must think also of the poor folk in the school-room, who are waiting patiently for your appearance. What shall we do? Shall we give up the Travesty? Or will someone go on and read the part of the King?”

“Oh, don’t stop the play! Let’s act!” cried some.

“Max and Austin’s fencing-match is so funny!” cried others.

“Well, I think myself we ought to proceed, and do our best. The question is, who can read the King? It must be someone who knows something about the piece—”

“Frances!” exclaimed Max immediately. “Frances has been at all the rehearsals; and she has often read the King’s part when she was hearing Austin and me say ours!”

Frances at first held back; but when she saw that she was really the best person to fill the breach, she made no more ado, but began to look about for a costume.

“If only Frank had thought of sending his,” said Max, regretful of the crimson velvet and ermine. “It would have done quite nicely for Frances. The tunic would have covered her frock.”

“We can hardly borrow it without leave, though. Well, I must let you settle the knotty point of costume for yourselves, youngsters, while I help my sister with the stage.”

Carlyon rushed off, nodding encouragingly to Frances, who had her eyes on the play-book and on every corner of the room in turn. Suddenly she darted over to a table covered by a crimson cloth.

“Hurrah!” she cried. “Here’s my tunic. A little ingenuity will soon drape it gracefully about my kingly person.”

Frances had seized the table-cover; and now, amid peals of laughter, she began, with Austin’s assistance, to pin herself into it. Max vanished from the room, returning in three minutes with two articles borrowed from friends among the Altruists’ relations in the audience.

“See, Frances! This fur-lined cape will make you a lovely cloak, and this fur tippet, put on back to front, will be your regal collar. About your neck and waist we will dispose the fairy prince’s gold chains, and he shall lend you his sword, likewise his cap.”

“Not his cap,” amended Austin, who was dancing a triumphant jig round his sister. “Frank left his crown here yesterday after rehearsal, and Frances can wear that.”

“And her sleeves will look all right. What a good thing your frock is of black velvet, Frances!”

By the time the young costumiers had finished they had turned out quite an effective King. Frances’s dark hair, waving to her shoulders, was pronounced “a first-rate wig” when the regal crown had been fitted on. The Carlyons declared the new King to be admirably attired; and Frances, relieved of anxiety about her costume, entered fully into the fun.

“I’m a ‘king of shreds and patches’ like Shakespeare’s man,” she chuckled; “but so long as my various garments hold together, I don’t mind! Max, if I could get a few minutes to look through this long speech, I believe I could manage without the book. I’ve heard Frank say his part ever so often.”

“You’ve helped everybody, Frances,” said Max, remembering gratefully his own indebtedness, “and now you’re going to shine yourself. You’ll have time to read up your part before you go on.”

The spirit of true burlesque is rare among amateurs; but youngsters who act for the fun of the thing, and not merely to “show off”, are often capable of excellent comedy. Carlyon had chosen with care the boys and girls who were to perform in the Travesty, and had trained them sufficiently but not too much. Entering completely into the humour of parody, one and all acted with plenty of vigour and without a trace of self-consciousness. Max and Austin had arranged a serio-comic fencing-match, which was brought to a melodramatic finish by a clever rapier trick. Frances’s play with the poisoned cup sent Betty, the lackadaisical Queen, into a series of private giggles, which she was compelled to conceal by an unexpectedly rapid demise. At last the curtain rang down on Austin’s farewell speech.

The boys and girls who during the long evening had figured on the platform assembled in the green-room for a brief chatter over their experiences. They were in high spirits and honestly happy; for they felt that they had done their best, and that their best had given several bright and pleasant hours to folks whose lives were but dull and gray.

Buns, sandwiches, and lemonade provided the Altruists’ modest refreshment. They had thoroughly earned their supper, but they hurried through it in order to make an appearance at the feast-tables of their guests. There was neither time nor place for change of dress; so the actors in their motley garb now mingled with their audience, greatly to the latter’s delight. Sweets and bon-bons tasted twice as good when handed round by Teddy in pink satin, and Lilla in white; and a whole troop of little fairies dispensed almonds and raisins at a lavish rate. The movement of the guests to the supper-tables at the end of the room was the signal for the retirement of upper-class Woodend to the neighbourhood of the platform, whence it watched its young people justifying their motto, “Help Others”.

“Austin,” whispered Frances, “aren’t you sorry poor Jim isn’t here?”

“Jim?” questioned her brother. “Why, wouldn’t he have been a cut above these good folk?”

“Oh, yes, of course. He wouldn’t need anyone to give him supper or a woollen comforter, I suppose. But he could have seen the acting, and he would have helped us.”

“Really, Frances, you are ridiculous. You have such a fancy for Jim—as though we could have had a fellow like that tagging on to us all the evening.”

“I could have put up with him very well,” returned Frances calmly; “and he would have been very useful. Don’t you be ridiculous, Austin.”

Austin muttered something about not wanting “loafing cads” in his vicinity; and was called so severely to task for his unmannerly epithet that he retired to grumble mildly in Max’s ear. But Max, too, liked Jim, and regretted the lad’s absence and the cause of it. He was sure that Frances was thinking pitifully of Jim’s lonely Christmas, and his sympathy was with Frances, not with her brother. Austin saw that his grumble must seek another sympathizer, and while looking for one, he noticed an old man’s empty plate, and flew to fulfil the duty of an Altruist host.

Supper was followed by a distribution of gifts. The presents numbered two for each person, and the ambition of the society had decreed that they should be strictly useful and of a kind to give some real comfort to the recipients. Thus, flannel shirts, knitted vests and socks, and cardigan jackets were handed to the men; while the women received warm skirts, bodices, and petticoats, “overall” aprons, and woollen shawls. Crimson was the hue of most of the clothing, and Max’s prophecy concerning the Altruist village seemed on the way to fulfilment. Thanks came heartily and in full measure from the delighted guests; and when their best spokesman had been put forward to offer the gratitude of the poor of Woodend to “the young ladies and gentlemen what had shown them a kindness they’d never forget”, good-byes became general, the village-folk trooped out, and the happy evening was really over.

Mrs. Morland went home alone in her carriage, promising to send it back for Frances and Austin, who were to take Max with them and set him down at his father’s gate. A wonderful amount of consideration from Woodend invalids had left Dr. Brenton free for a whole e