CHAPTER XVI

"STOP, LOOK, LISTEN"

Bassett and Atwill held a conference the next day and the interview was one of length. The manager of the "Courier" came to the office in the Boordman Building at eleven o'clock, and when Harwood went to luncheon at one the door had not been opened. Miss Farrell, returning from her midday repast, pointed to the closed door, lifted her brows, and held up her forefinger to express surprise and caution. Miss Farrell's prescience was astonishing; of women she held the lightest opinion, Dan had learned; her concern was with the affairs of men. Harwood, intent upon the compilation of a report of the paper-mill receivership, was nevertheless mindful of the unwonted length of the conference. When he returned from luncheon, Bassett had gone, but he reappeared at three o'clock, and a little later Atwill came back and the door closed again. This second interview was short, but it seemed to leave Bassett in a meditative frame of mind. Wishing to discuss some points in the trial balance of the receiver's accountant, Harwood entered and found Bassett with his hat on, slowly pacing the floor.

"Yes; all right; come in," he said, as Harwood hesitated. He at once addressed himself to the reports with his accustomed care. Bassett carried an immense amount of data in his head. He understood bookkeeping and was essentially thorough. Dan constantly found penciled calculations on the margins of the daily reports from the paper-mill, indicating that Bassett scrutinized the figures carefully, and he promptly questioned any deviation from the established average of loss and gain. Bassett threw down his pencil at the end of half an hour and told Dan to proceed with the writing of the report.

"I'd like to file it personally so I can talk over the prospect of getting an order of sale before the judge goes on his vacation. We've paid the debts and stopped the flow of red ink, so we're about ready to let go."

While they were talking Miss Farrell brought in a telegram for Harwood; it was the summons from Mrs. Owen that he had been waiting for; she bade him come to Montgomery the next day. He handed the message to Bassett.

"Go ahead. I'll go over there if you like and find you the necessary bondsmen. I know the judge of the circuit court at Montgomery very well. You go in the morning? Very well; I'll stay here till you get back. Mrs. Bassett will be well enough to leave the sanatorium in a few days, and I'm going up to Waupegan to get the house ready."

"It will be pleasant for Mrs. Bassett to have Mrs. Owen there this summer. Anybody is lucky to have a woman of her qualities for a neighbor."

"She's a noblewoman," said Bassett impressively, "and a good friend to all of us."

On the train the next morning Harwood unfolded the day's "Courier" in the languidly critical frame of mind that former employees of newspapers bring to the reading of the journals they have served. He scanned the news columns and opened to the editorial page. The leader at once caught his eye. It was double-leaded,—an emphasis rarely employed at the "Courier" office, and was condensed in a single brief paragraph that stared oddly at the reader under the caption "STOP, LOOK, LISTEN." It held Harwood's attention through a dozen amazed and mystified readings. It ran thus:—

It has long been Indiana's proud boast that money unsupported by honest merit has never intruded in her politics. A malign force threatens to mar this record. It is incumbent upon honest men of all parties who have the best interests of our state at heart to stop, look, listen. The COURIER gives notice that it is fully advised of the intentions, and perfectly aware of the methods, by which the fair name of the Hoosier State is menaced. The COURIER, being thoroughly informed of the beginnings of this movement, whose purpose is the seizure of the Democratic Party, and the manipulation of its power for private ends, will antagonize to the utmost the element that has initiated it. Honorable defeats the party in Indiana has known, and it will hardly at this late day surrender tamely to the buccaneers and adventurers that seek to capture its battleflag. This warning will not be repeated. Stop! Look! Listen!

From internal evidence Harwood placed the authorship readily enough: the paragraph had been written by the chief editorial writer, an old hand at the game, who indulged frequently in such terms as "adventurer" and "buccaneer." It was he who wrote sagely of foreign affairs, and once caused riotous delight in the reporters' room by an editorial on Turkish politics, containing the phrase, "We hope the Sultan—" But not without special authority would such an article have been planted at the top of the editorial page, and beyond doubt these lines were the residuum of Bassett's long interview with Atwill. And its aim was unmistakable: Mr. Bassett was thus paying his compliments to Mr. Thatcher. The encounter at the Country Club might have precipitated the crisis, but, knowing Bassett, Dan did not believe that the "Courier's" batteries would have been fired on so little provocation. Bassett was not a man to shoot wildly in the dark, nor was he likely to fire at all without being sure of the state of his ammunition chests. So, at least, Harwood reasoned to himself. Several of his fellow passengers in the smoking-car were passing the "Courier" about and pointing to the editorial. All over Indiana it would be the subject of discussion for a long time to come; and Dan's journalistic sense told him that in the surrounding capitals it would not be ignored.

"If Thatcher and Bassett get to fighting, the people may find a chance to sneak in and get something," a man behind Dan was saying.

"Nope," said another voice; "there won't be 'no core' when those fellows get through with the apple."

"I can hear the cheering in the Republican camp this morning," remarked another voice gleefully.

"Oh, pshaw!" said still another speaker; "Bassett will simply grind Thatcher to powder. Thatcher hasn't any business in politics anyhow and doesn't know the game. By George, Bassett does! And this is the first time he's struck a full blow since he got behind the 'Courier.' Something must have made him pretty hot, though, to have let off a scream like that."

Harwood was interested in these remarks because they indicated a prevalent impression that Bassett dominated the "Courier," in spite of the mystery with which the ownership of the paper was enveloped. The only doubt in Harwood's own mind had been left there by Bassett himself. He recalled now Bassett's remark on the day he had taken him into his confidence in the Ranger County affair. "I might have some trouble in proving it myself," Bassett had said. Harwood thought it strange that after that first deliberate confidence and his introduction to Atwill, Bassett had, in this important move, ignored him. It was possible that his relations with Allen Thatcher, which Bassett knew to be intimate, accounted for the change; or it might be due to a lessening warmth in Bassett's feeling toward him. He recalled now that Bassett had lately seemed moody,—a new development in the man from Fraser,—and that he had several times been abrupt and unreasonable about small matters in the office. Certain incidents that had appeared trivial at the time of their occurrence stood forth disquietingly now. If Bassett had ceased to trust him, there must be a cause for the change; slight manifestations of impatience in a man so habitually calm and rational might be overlooked, but Dan had not been prepared for this abrupt cessation of confidential relations. He was a bit piqued, the more so that this astounding editorial indicated a range and depth of purpose in Bassett's plans that Dan's imagination had not fathomed. He tore out the editorial and put it away carefully in his pocketbook as Montgomery was called.

A messenger was at the station to guide him to the court-house, where he found Mrs. Owen and Sylvia waiting for him in the private room of the judge of the circuit court. Mrs. Owen had, in her thorough fashion, arranged all the preliminaries. She had found in Akins, the president of the Montgomery National Bank, an old friend, and it was her way to use her friends when she needed them. At her instance, Akins and another resident freeholder had already signed the bond when Dan arrived. Dan was amused by the direct manner in which Mrs. Owen addressed the court; the terminology pertaining to the administration of estates was at her fingers' ends, and there was no doubt that the judge was impressed by her.

"We won't need any lawyer over here, Daniel; you can save the estate lawyer's fees by acting yourself. I guess that will be all right, Judge?"

His Honor said it would be; people usually yielded readily to Mrs. Owen's suggestions.

"You can go up to the house now, Sylvia, and I'll be along pretty soon. I want to make a memorandum for an inventory with Daniel."

At the bank Akins gave them the directors' room, and Andrew Kelton's papers were produced from his box in the safety vault. Akins explained that Kelton had been obliged to drop life insurance policies for a considerable amount; only one policy for two thousand dollars had been carried through. There were a number of contracts with publishers covering the copyrights in Kelton's mathematical and astronomical textbooks. The royalties on these had been diminishing steadily, the banker said, and they could hardly be regarded as an asset.

"Life insurance two thousand, contracts nothing, and the house is worth two with good luck. Take it all in—and I reckon this is all—we'll be in luck to pinch a little pin-money out of the estate for Sylvia. It's more than I expected. You think there ain't anything else, Mr. Akins?"

"The Professor talked to me about his affairs frequently, and I have no reason to think there's anything more. He had five thousand dollars in government bonds, but he sold them and bought shares in that White River Canneries combination. A lot of our Montgomery people lost money in that scheme. It promised fifteen per cent—with the usual result."

"Yes. Andrew told me about that once. Well, well!"

"He had money to educate his granddaughter; I don't know how he raised it, but he kept it in a special account in the bank. He told me that if he died before she finished college that was to be applied strictly to her education. There is eight hundred dollars left of that."

"Sylvia's going to teach," said Mrs. Owen. "I've been talking to her and she's got her plans all made. She's got a head for business, that girl, and nothing can shake her idea that she's got a work to do in the world. She knows what she's going to do every day for a good many years, from the way she talks. I had it all fixed to take her with me up to Waupegan for the summer; thought she'd be ready to take a rest after her hard work at college, and this blow of her grandpa dying and all; but not that girl! She's going to spend the summer taking a normal course in town, to be ready to begin teaching in Indianapolis next September. I guess if we had found a million dollars in her grandpa's box it would have been the same. When you talk about health, she laughs; I guess if there's a healthy woman on earth it's that girl. She says she doubled all her gymnasium work at college to build herself up ready for business. You know Dr. Wandless's daughter is a Wellesley woman, and keeps in touch with the college. She wrote home that Sylvia had 'em all beat a mile down there; that she just walked through everything and would be chosen for the Phi Beta Kappa—is that right, Daniel? She sort o' throws you out of your calculations, that girl does. I'd counted on having a good time with her up at the lake, and now it looks like I'd have to stay in town all summer if I'm going to see anything of her."

It was clear enough that Mrs. Owen was not interesting herself in Sylvia merely because the girl was the granddaughter of an old friend; she admired Sylvia on her own account and was at no pains to disguise the fact. The Bassett expectations were, Dan reflected, scarcely at a premium to-day!

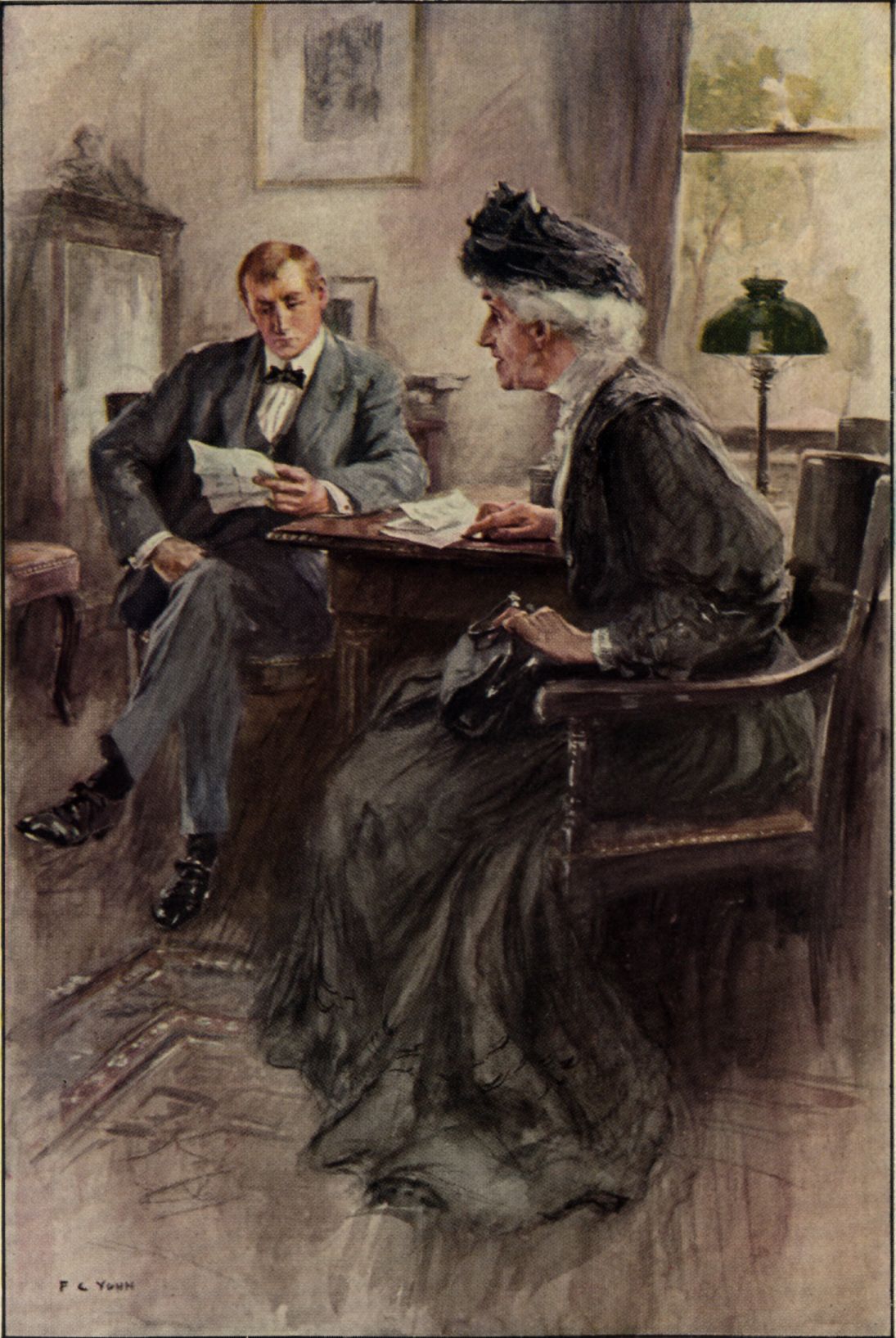

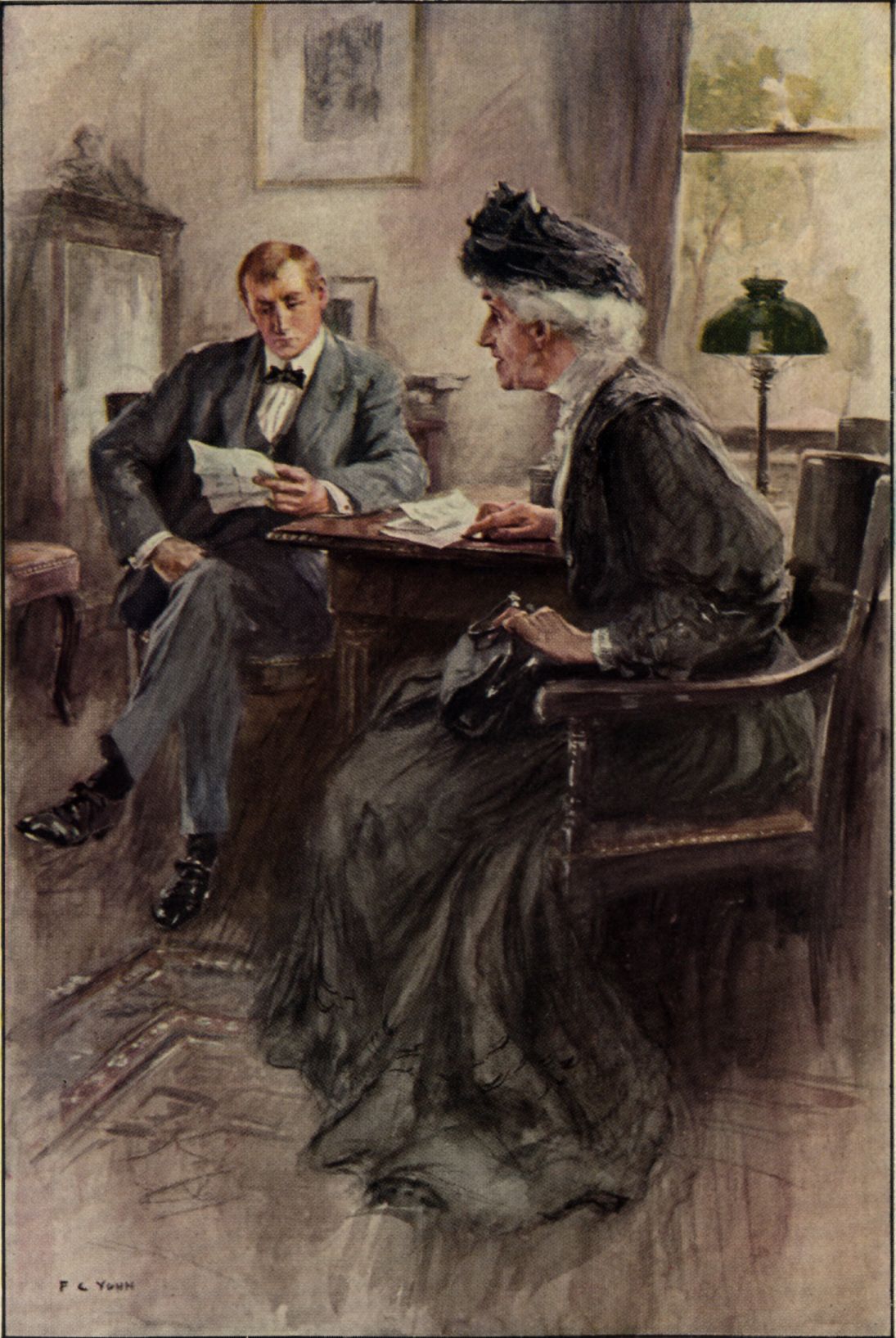

Mr. Akins returned the papers to the safety box, and when Mrs. Owen and Harwood were alone, she closed the door carefully.

"Now, Daniel," she began, opening her hand-satchel, "I always hold that this is a funny world, but that things come out right in the end. They mostly do; but sometimes the Devil gets into things and it ain't so easy. You believe in the Devil, Daniel?"

"Well, my folks are Presbyterians," said Dan. "My own religion is the same as Ware's. I'm not sure he vouches for the Devil."

"It's my firm conviction that there is one, Daniel,—a red one with a forked tail; you see his works scattered around too often to doubt it."

Dan nodded. Mrs. Owen had placed carefully under a weight a paper she had taken from her reticule.

"Daniel,"—she looked around at the door again, and dropped her voice,—"I believe you're a good man, and a clean one. And Fitch says you're a smart young man. It's as much because you're a good man as because you've got brains that I've called on you to attend to Sylvia's business. Now I'm going to tell you something that I wouldn't tell anybody else on earth; it's a sacred trust, and I want you to feel bound by a more solemn oath than the one you took at the clerk's office not to steal Sylvia's money."

She fixed her remarkably penetrating gaze upon him so intently that he turned uneasily in his chair. "It's something somebody who appreciates Sylvia, as I think you do, ought to know about her. Andrew Kelton told me just before Sylvia started to college. The poor man had been carrying it alone till it broke him down; he had never told another soul. I reckon it was the hardest job he ever did to tell me; and I wouldn't be telling you except somebody ought to know who's in a position to help Sylvia—sort o' look out for her and protect her. I believe"—and she put out her hand and touched his arm lightly— "I believe I can trust you to do that."

"Yes, Mrs. Owen."

She waited until he had answered her, and even then she was silent, lost in thought.

"Professor Kelton didn't know, Daniel," she began gravely, "who Sylvia's father was." She minimized the significance of this by continuing rapidly. "Andrew had quit the Navy soon after the war and came out here to Madison College to teach, and his wife had died and he didn't know what to do with his daughter. Edna Kelton was a little headstrong, I reckon, and wanted her own way. She didn't like living in a country college town; there wasn't anything here to interest her. I won't tell you all of Andrew's story, but it boils down to just this, that while Edna was in New York studying music she got married without telling where, or to whom. Andrew never saw her till she was dying in a hospital and had a little girl with her,—that's Sylvia. Now, whether there was any disgrace about it Andrew didn't know; and we owe it to that dead woman and to Sylvia to believe it was all right. You see what I mean, Daniel? Now that brings me down to what I want you to know. Somebody has been keeping watch of Sylvia,—Andrew told me that."

She was thinking deeply as though pondering just how much more it was necessary to tell him, and before she spoke she picked up the folded paper and read it through carefully. "When Andrew got this it troubled him a lot: the idea that somebody had an eye on the girl, and took enough interest in her to do this, made him uneasy. Sylvia never knew anything about it, of course; she doesn't know anything about anything, and she won't ever need to."

"As I understand you, Mrs. Owen, you want some friend of hers to be in a position to protect her if any one tries to harm her; you want to shield her from any evil that might follow her from her mother's errors, if they were indeed errors. We have no right to assume that she had done anything to be ashamed of. That's the only just position for us to take in such a matter."

"That's right, Daniel. I knew you'd see it that way. It looks bad, and Andrew knew it looked bad; but at my age I ain't thinking evil of people if I can help it. If a woman goes wrong, she pays for it—keeps on paying after she's paid the whole mortgage. That's the blackest thing in the world—that a woman never shakes a debt like that the way a man can. You foreclose on a woman and take away everything she's got; put her clean through bankruptcy, and the balance is still against her; but we can't make over society and laws just sitting here talking about it. I reckon Edna Kelton suffered enough. But we don't want Sylvia to suffer. She's entitled to a happy life, and we don't want any shadows hanging over her. Now that her grandpa's gone she can't go behind what he told her,—poor man, he had trouble enough answering the questions she had a right to ask; and he had to lie to her some."

"Yes; I suppose she will be content now; she will feel that what he didn't tell her she will never know. She's not a morbid person, and won't be likely to bother about it."

"No; I ain't afraid of her brooding on what she doesn't know. It's the fear it may fly up and strike her when she ain't looking that worries me, and it worried the Professor, too. That was why he told me. I guess when he talked to me that time he knew his heart was going to stop suddenly some day. And he'd got a hint that somebody was interested in watching Sylvia—sort o' keeping track of her. And there was conscience in it; whoever it is or was hadn't got clean away from what he'd done. Now I had a narrow escape from letting Sylvia see this letter. It was stuck away in a tin box in Andrew's bedroom, along with his commissions in the Navy. I was poking round the house, thinking there might be things it would be better not to show Sylvia, and I struck this box, and there was this letter, stuck away in the middle of the package. I gave Sylvia the commissions, but she didn't see this. I don't want to burn it till you've seen it. This must have been what Andrew spoke to me about that time; it was hardly before that, and it might have been later. You see it isn't dated. He started to tear it up, but changed his mind, so now we've got to pass on it."

She pushed the letter across the table to Harwood, and he read it through carefully. He turned it over after the first reading, and the word "Declined," written firmly and underscored, held him long—so long that he started when Mrs. Owen roused him with "Well, Daniel?"

He knew before he had finished reading that it was he who had borne the letter to the cottage in Buckeye Lane, unless there had been a series of such communications, which was unlikely on the face of it. Mrs. Owen had herself offered confirmation by placing the delivery of the dateless letter five years earlier. The internal evidence in the phrases prescribing the manner in which the verbal reply was to be sent, and the indorsement on the back of the sheet, were additional corroboration. It was almost unimaginable that the letter should have come again to his hand. He realized the importance and significance of the sheet of paper with the swiftness of a lightning flash; but beyond the intelligence conveyed by the letter itself there was still the darkness to grope in. His wits had never worked so rapidly in his life; he felt his heart beating uncomfortably; the perspiration broke out upon his forehead, and he drew out his handkerchief and mopped his face.

"It's certainly very curious, very curious indeed," he said with all the calmness he could muster. "But it doesn't tell us much."

"It wasn't intended to tell anything," said Mrs. Owen. "Whoever wrote that letter, as I told you, was troubled about Sylvia. I reckon it was a man; and I guess it's fair to assume that he felt under obligations, but hadn't the nerve to face 'em as obligations. Is that the way it strikes you?"

WHOEVER WROTE THAT LETTER WAS TROUBLED ABOUT SYLVIA

"That seems clear enough," he replied lamely. He made a pretense of rereading the letter, but only detached phrases penetrated to his consciousness. His imagination was in rebellion against the curbing to which he strove to subject it. When he had borne his answer back to Fitch's office and been discharged with the generous payment of one hundred dollars for his services as messenger, just what had been the further history of the transaction? He had so far controlled his agitation that he was able to continue discussing the letter formally with the kind old woman who had placed the clue in his hands. He was little experienced in the difficult art of conversing with half a mind, and a direct question from Mrs. Owen roused him to the necessity of heeding what she was saying. He had resolved, however, that he would not tell her of his own connection with the message that lay on the table before them. He needed time in which to consider; he must not add a pebble's weight to an avalanche that might go crashing down upon the innocent. His training had made him wary of circumstantial evidence; after all it was possible that this was not the letter he had carried to Professor Kelton. It would be very like Mrs. Owen, if she saw that anything could be gained by such a course, to go direct to Fitch and demand to know the source of the offer that had passed through his hands so mysteriously; but Fitch had not known the contents of the letter, or he had said as much to Harwood. There was also the consideration, and not the lightest, that Dan was bound in honor to maintain the secrecy Fitch had imposed upon him. The lawyer had confided the errand to him in the belief that he would accept the mission in the spirit in which it was entrusted to him, and his part in the transaction was a matter between himself and Fitch and did not concern Mrs. Owen in any way whatever. No possible benefit could accrue to Sylvia from a disclosure of his suspicion that he had borne the letter to her grandfather. Mrs. Owen had given him the letter that he might be in a position to protect Sylvia, and there was nothing incompatible between this confidence and his duty to Fitch, who continued to be a kind and helpful friend. He dreaded the outcome of an interview between this shrewd, penetrating, and indomitable woman and the lawyer. The letter, cold and colorless in what it failed to say, and torn half across to mark the indecision of the old professor, had in it a great power for mischief.

While Harwood's mind was busy with these reflections he had been acquiescing in various speculations in which Mrs. Owen had been indulging, without really being conscious of their import.

"I don't know that any good can come of keeping the letter, Daniel. I reckon we might as well tear it up. You and I know what it is, and I've been studying it for a couple of days without seeing where any good can come of holding it. You might burn it in the grate there and we'll both know it's out of the way. I guess that person feels that he done his whole duty in making the offer and he won't be likely to bother any more. That conscience was a long time getting waked up, and having done that much it probably went to sleep again. There's nothing sleeps as sound as a conscience, I reckon, and I shouldn't be a bit surprised if mine took a nap occasionally. Better burn that little document, Daniel, and we'll be rid of it and try to forget it."

"No; I don't believe I'd do that," he said slowly. "It might be better to hold on to it, at least until the estate is closed up. You can't tell what's behind it." And then, groping for a plausible reason, he added: "The author of the letter may be in a position to annoy Sylvia by filing a claim against the Professor's estate, or something of that kind. It's better not to destroy the only thing we have that might help if that should occur. I believe it's best to hold on to it till the estate's settled."

This was pretty lame, as he realized, but his caution pleased her, and she acquiesced. She was anxious to leave no ground for anyone to rob Sylvia of her money, and if there was any remote possibility that the letter might add to the girl's security she was willing that it should be retained. She sent Dan out into the bank for an envelope, and when it was brought, sealed up the letter and addressed it to Dan in her own hand and marked it private.

"You take good care of that, Daniel, and when you get the estate closed up you burn it."

"Yes, it can do no harm to hold it a little while," he said with affected lightness.