CHAPTER XXXI

SYLVIA ASKS QUESTIONS

The Wares had asked Sylvia to dine with them on Friday evening a fortnight later, and Harwood was to call for her at the minister's at nine o'clock. Sylvia went directly to the Wares' from school, and on reaching the house learned that Mrs. Ware had not come home and that the minister was engaged with a caller in the parlor. Sylvia, who knew the ways of the house well, left her wraps in the hall and made herself comfortable in the study, that curious little room that was never free from the odor of pipe smoke, and where an old cavalry sabre hung above the desk upon which in old times many sermons had been written. A saddle, a fishing-rod, and a fowling-piece dwelt together harmoniously in one corner, and over the back of a chair hung a dilapidated corduroy coat.

It had been whispered in orthodox circles that Ware had amused himself one winter after his retirement by profanely feeding his theological library into the furnace. However true this may be, few authors were represented in his library, and these were as far as possible compressed in one volume. Shakespeare, Milton, Emerson, Arnold, and Whittier were always ready to his hand; and he kept a supply of slender volumes of Sill's "Poems" in a cupboard in the hall and handed them out discriminatingly to his callers. The house was the resort of many young people, some of them children of Ware's former parishioners, and he was much given to discussing books with them; or he would read aloud—"Sohrab and Rustum," Lowell's essay on Lincoln, or favorite chapters from "Old Curiosity Shop"; or again, it might be a review article on the social trend or a fresh view of an old economic topic. The Wares' was the pleasantest of small houses and after Mrs. Owen's the place sought oftenest by Sylvia.

"There's a gentleman with Mr. Ware: he's been here a long time," said the maid, lingering to lay a fresh stick of wood on the grate fire.

Sylvia, warming her hands at the blaze, heard the faint blur of voices from the parlor. She surveyed the room with the indifference of familiarity, glanced at a new magazine, and then sat down at the desk and picked up a book she had never noticed before. She was surprised to find it a copy of "Society and Solitude" that did not match the well-thumbed set of Emerson—one of the few "sets" Ware owned. She passed her hand over the green covers, that were well worn and scratched in places. The fact that the minister boasted in his humorous way of never wasting money on bindings caused Sylvia to examine this volume with an attention she would not have given it in any other house. On the fly leaf was written in pencil, in Ware's rough, uneven hand, an inscription which covered the page, with the last words cramped in the lower corner. These were almost illegible, but Sylvia felt her way through them slowly, and then turned to the middle of the book quickly with an uncomfortable sense of having read a private memorandum of the minister's. The margins of his books she knew were frequently scribbled over with notes that meant nothing whatever to any one but Ware himself. After a moment her eyes sought again irresistibly the inscription. She re-read it slowly:—

"The way of peace they know not; and there is no judgment in their goings; they have made them crooked paths; whosoever goeth therein shall not know peace. Tramping in Adirondacks. Baptized Elizabeth at Harris's."

It was almost like eavesdropping to come in this way upon that curiously abrupt Ware-like statement of the minister's: "Tramping in Adirondacks. Baptized Elizabeth at Harris's."

The discussion in the parlor had become heated, and occasionally words in a voice not Ware's reached Sylvia distinctly. Some one was alternately beseeching and threatening the minister. It was clear from the pauses in which she recognized Ware's deep tones that he was yielding neither to the importunities nor the threats of his blustering caller. Sylvia had imagined that the storms of life had passed over the retired clergyman, and she was surprised that such an interview should be taking place in his house. She was about to retreat to the dining-room to be out of reach of the voices when the parlor door opened abruptly and Thatcher appeared, with anger unmistakably showing in his face, and apparently disposed to resume in the hall the discussion which the minister had terminated in the library. Thatcher seemed balder and more repellent than when she had first seen him on the floor of the convention hall on the day Harwood uttered Bassett's defiance. Sylvia rose with the book still in her hand and walked to the end of the room; but any one in the house might have heard what Thatcher was saying.

"That's the way with you preachers; you talk about clean politics, and when we get all ready to clean out a bad man, you duck; you're a lot of cowardly dodgers. I tell you, I don't want you to say a word or figure in this thing at all; but you give me that book and I'll scare Mort Bassett out of town. I'll scare him clean out of Indiana, and he'll never show his head again. Why, Ware, I've been counting on it, that when you saw we were in a hole and going to lose, you'd come down from your high horse and help me out. I tell you, there's no doubt about it; that woman's the woman I'm looking for! I guessed it the night you told that story up there in the house-boat."

"Quit this business, Ed," the minister was saying; "I'm an old friend of yours. But I won't budge an inch. I'd never breathed a word of that story before and I shouldn't have told it that night. It was so far back that I thought it was safe. But your idea that Bassett had anything to do with that is preposterous. Your hatred of him has got the better of you, my friend. Drop it: forget it. If you can't whip him fair, let him win."

"Not much I won't; but I didn't think you'd go back on me; I thought better of you than that!"

Thatcher strode to the door and went out, slamming it after him.

The minister peered into the library absently, and then, surprised to find Sylvia, advanced to meet her, smiling gravely. He took both her hands, and held them, looking into her face.

"What's this you've been reading? Ah, that book!" The volume slipped into his hands and he glanced at it, frowning impatiently. "Poor little book. I ought to have burned it years ago; and I ought to have learned by this time to keep my mouth shut. They've always said I look like an Indian, but an Indian never tells anything. I've told just one story too many. Mea maxima culpa!"

He sat down in the big chair beside his desk, placed the book within reach, and kept touching it as he talked.

"I saw Mr. Thatcher," said Sylvia. "He seemed very much aroused. I couldn't help hearing a word now and then."

"That's all right, Sylvia. I've known Thatcher for years, and last fall I went up to his house-boat on the Kankakee for a week's shooting. Allen and Dan Harwood were the rest of the party—and I happened to tell the story of this little book—an unfinished story. We ought never to tell stories until they are finished. And it seems that Thatcher, with a zeal worthy of a better cause, has been raking up the ashes of an old affair of Bassett's with a woman, and he's trying to hitch it on to the story I told him about this book. He says by shaking this at Bassett he can persuade him that he's got enough ammunition to blow him out of the water. But I don't believe a word of it; I won't believe such a thing of Morton Bassett. And even if I did, Thatcher can't have that book. I owe it to the woman whose baby I baptized up there in the hills to keep it. And the woman may be living, too, for all I know. I think of her pretty often. She was game; wouldn't tell anything. If a man had deceived her she stood by him. Whatever she was—I know she was not bad, not a bit of it—the spirit of the hills had entered into her—and those are cleansing airs up there. I suppose it all made the deeper impression on me because I was born up there myself. When I strike Adirondacks in print I put down my book and think a while. It's a picture word. It brings back my earliest childhood as far as I can remember. I call words that make pictures that way moose words; they jump up in your memory like a scared moose in a thicket and crash into the woods like a cavalry charge. I can remember things that happened when I was three years old: one day father shot a deer in our cornfield and I recall it perfectly. The general atmosphere of the old place steals over me yet. The very thought of the pointed spruces, the feathery tamaracks, all the scents and sounds of summer, and the long, white winters, does my soul good now. The old Hebrews understood the effect of landscape on character. They knew most everything, those old chaps. 'I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills from whence cometh my help.' Any strength there is in me dates back to the hills of my youth. I'd like to go back there to die when the bugle calls."

Mrs. Ware had not yet come in. Ware lighted the lamp and freshened the fire. While he was doing this, Sylvia moved to a chair by the table and picked up the book. What Ware had said about the hills of his youth, the woods, the word tamarack that he had dropped carelessly, touched chords of memory as lightly as a breeze vibrates a wind harp. Was this merely her imagination that had been stirred, or was it indeed a recollection? Often before she had been moved by similar vague memories or longings, whatever they were. They had come to trouble her girlhood at Montgomery, when the snow whitened the campus and the wind sang in the trees. She was grateful that the minister had turned his back. Her hands trembled as she glanced again at the scribbled fly leaf; and more closely at the words penciled at the bottom: "Baptized Elizabeth at Harris's." Thatcher wanted this book to use against Bassett. Bassett was a collector of fine bindings; she had heard it spoken of in the family. It was part of Marian's pride in her father that he was a bookish man. When the minister returned to his seat Sylvia asked as she put down the book:—

"Who was Elizabeth?"

And then, little by little, in his abrupt way, he told the story, much as he had told it that night on the Kankakee, with pauses for which Sylvia was grateful—they gave her time for thought, for filling in the lapses, for visualizing the scene he described. And the shadow of the Morton Bassett she knew crept into the picture. She recalled their early meetings, that first brief contact on the shore of the lake; their talk on the day following the convention when she had laughed at him; that wet evening when they met in the street and he had expressed his interest in Harwood and the hope that she might care for the young lawyer. With her trained habits of reasoning she rejected this or that bit of testimony as worthless; but even then enough remained to chill her heart. Her hands were cold as she clasped them together. Who was Elizabeth? Ah, who was Sylvia? The phrase of the song that had brought her to tears that starry night on the lake when Dan Harwood had asked her to marry him smote her again. Her grandfather's evasion of her questions about her father and mother, and the twinges of heartache she had experienced at college when other girls spoke of their homes, assumed now for the first time a sinister meaning. Had she, indeed, come into the world in dishonor, and had she in truth known that far hill country, with its evergreens and glistening snows?

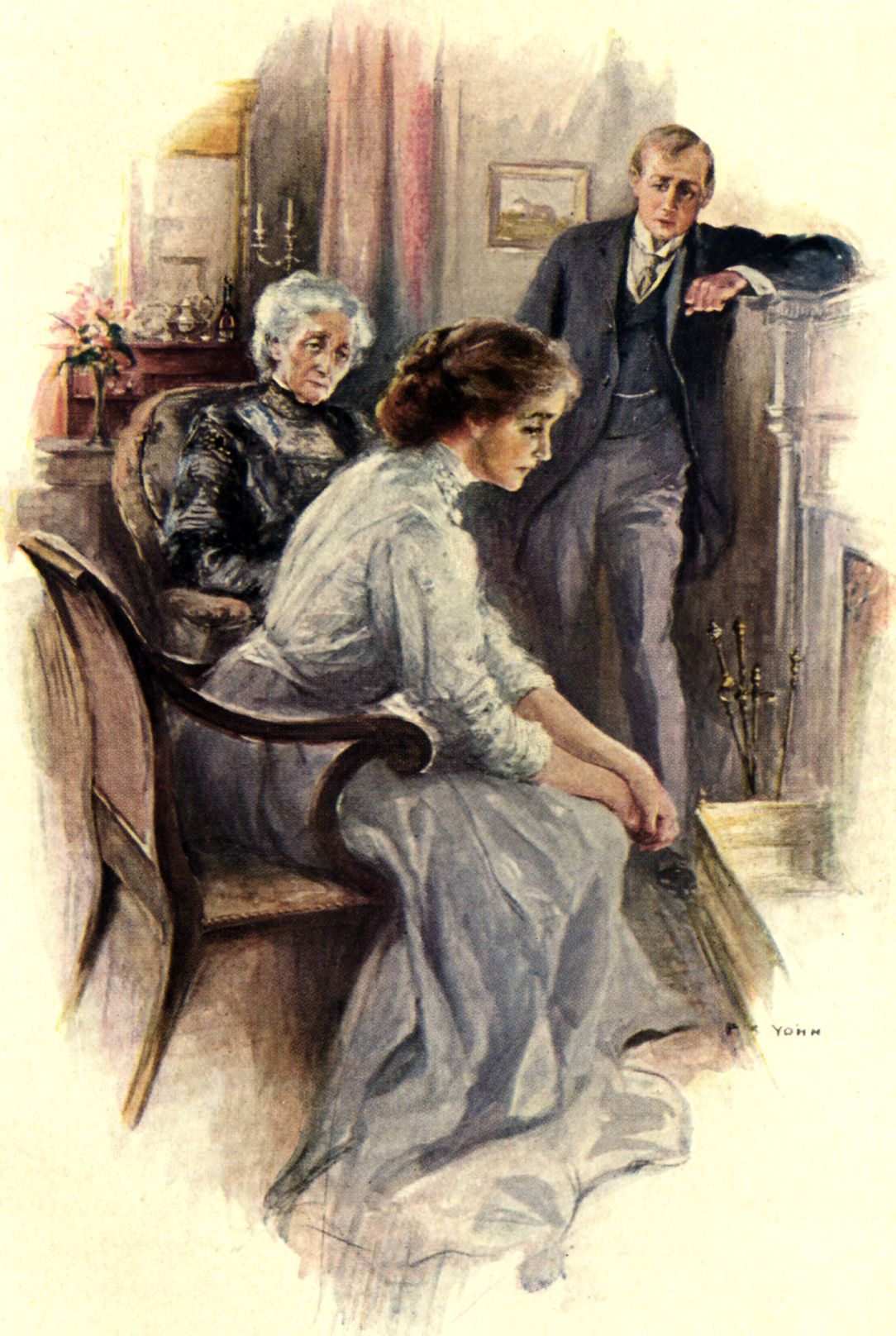

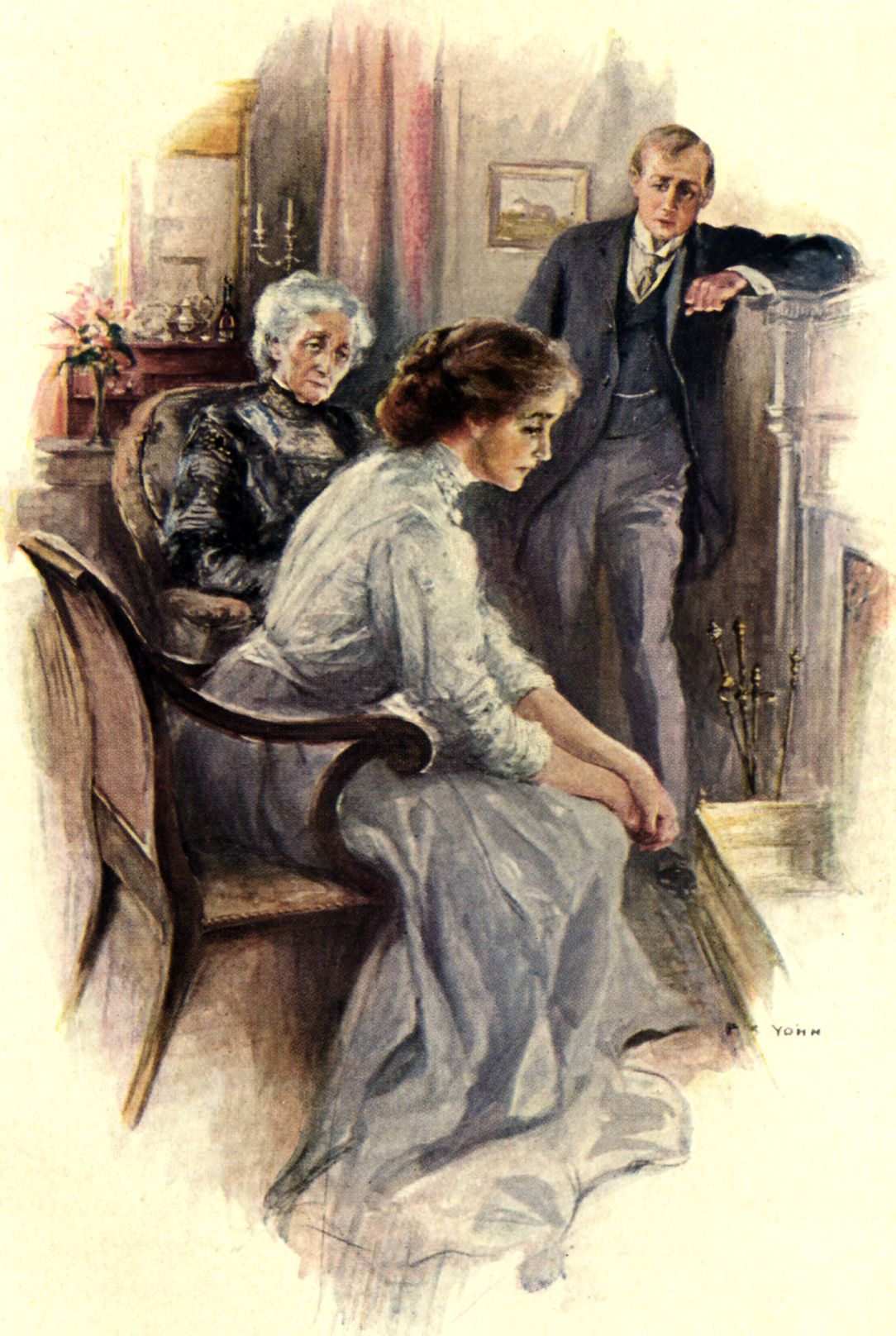

Ware had finished his story, and sat staring into the crackling fire. At last he turned toward Sylvia. In the glow of the desk lamp her face was white, and she gazed with unseeing eyes at the inscription in the book.

The silence was still unbroken when a few minutes later Mrs. Ware came in with Harwood, whom she had met in the street and brought home to dinner.

Dan was full of the situation in the legislature, and the table talk played about that topic.

"We're sparring for time, that's all, and the people pay the freight! The deadlock is clamped on tight. I never thought Thatcher would prove so strong. I think we could shake loose enough votes from both sides to precipitate a stampede for Ramsay, but he won't hear to it. He says he wants to do the state one patriotic service before he dies by cleaning out the bosses, and he doesn't want to spoil the record by taking the senatorship himself. Meanwhile Bassett stands fast and there's no telling when he'll break through Thatcher's lines."

"Thatcher was here to see me to-day—the third time. He won't come back. You know what he's after?" said Ware.

"Yes; I understand," Dan answered.

"There won't be anything of that kind, will there, Dan?"

Dan shrugged his shoulders, and glanced at Sylvia and Mrs. Ware.

"Mrs. Ware knows about it; I had to tell her," remarked the minister, chuckling. "When Ed Thatcher makes two calls on me in one week, and one of them at midnight, there's got to be an explanation. And Sylvia heard him raving before I showed him out this afternoon."

Sylvia's plate was untouched; her eyes searched those of the man who loved her before she spoke.

"That's an ethical point, Mr. Ware. If it were necessary to use that,—if every other resource failed,—would you use it?"

"No! Not if Bassett's success meant the utter destruction of the state. I don't believe a word of it. I haven't the slightest confidence in Thatcher's detective work, and the long arm of coincidence has to grasp something firmer than my pitiful little book to convince me."

Dan shook his head.

"He doesn't need the book, Mr. Ware. I've seen the documents in the case. Most of the evidence is circumstantial, but you remember what your friend Thoreau said about circumstantial evidence—something to the effect that it's sometimes pretty convincing, as when you find a trout in the milk."

"But has Thatcher found the trout?"

"Well, no; he hasn't exactly found the trout, but there's enough, there's altogether too much!" ended Dan despairingly. "The caucus doesn't meet again till to-morrow night, when Thatcher promises to show his hand. I'm going to put in the time trying to persuade Ramsay to come round."

"You might take it yourself, Dan," suggested Mrs. Ware.

"Oh, I'm not eligible; I'm a little shy of being old enough! And besides, I couldn't allow Ramsay to prove himself a better patriot than I am. There are plenty of fellows who have no such scruples, and we've got to look out or Bassett will shift suddenly to some man of his own if he finds he can't nominate himself."

"But do you think he has any idea what Thatcher has up his sleeve?" asked Ware.

"It's possible; I dare say he knows it. He's always been master of the art of getting information from the enemy's camp. But Thatcher has shown remarkable discretion in managing this. He tells me solemnly that nobody on earth knows his intentions except you, Allen, and me. He's saving himself for a broadside, and he wants its full dramatic effect."

Sylvia had hardly spoken during this discussion; but the others looked at her curiously as she said:—

"I don't think he has it to fire; it's incredible; I don't believe it."

"Neither do I, Sylvia," said the minister earnestly.

The talk at the Wares' went badly that evening. Harwood's mind was on the political situation. As he sat in the minister's library he knew that in upper chambers of the State House, and in hotels and boarding-houses, members of the majority in twos and threes, or here and there a dozen, were speculating and plotting. The deadlock was becoming intolerable. Interest in the result was keen in all parts of the country, and the New York and Chicago newspapers had sent special representatives to watch the fight. Dan was sick of the sight and sound of it. In the strict alignment of factions he had voted with Thatcher, yet he told himself he was not a Thatcher man. He had personally projected Ramsay's name one night in the hope of breaking the Bassett phalanx, but the only result was to arouse Thatcher's wrath against him. Bassett's men believed in Bassett. The old superstition as to his invulnerability had never more thoroughly possessed the imaginations of his adherents. Bassett was not only himself again, but his iron grip seemed tighter than ever He was making the fight of his life, and he was beyond question a "game" fighter, the opposition newspapers that most bitterly opposed Bassett tempered their denunciations with this concession. Dan fumed at this, such bosses were always game fighters, they had to be, and the readiness of Americans to admire the gameness of the Bassetts deepened his hostility. The very use of sporting terminology in politics angered him. In his mind the case was docketed not as Thatcher versus Bassett, but as Thatcher and Bassett versus the People. It all came to that. And why should not the People—the poor, meek, long-suffering People, the "pee-pul" of familiar derision—sometimes win? His pride in the state of his birth was strong; his pride in his party was only second to it. He would serve both if he could. Not only must Bassett be forever put down, but Thatcher also; and he assured himself that it was not the men he despised, but the wretched, brutal mediæval system that survived in them. And so pondering, it was no wonder that Dan brought no joy to John Ware's library that night. The minister himself seemed unwontedly preoccupied; Sylvia stared at the fire as though seeking in the flames answers to unanswerable questions. Mrs. Ware sought vainly to bring cheer to the company:

Shortly after eight o'clock, Sylvia rose to leave.

"Aunt Sally got home from Kentucky this afternoon, and I must drop in for a minute, Dan, if you don't mind."

Sylvia hardly spoke on the way to Mrs. Owen's. Since that night on the lake she had never been the same, or so it seemed to Dan. She had gone back to her teaching, and when they met she talked of her work and of impersonal things. Once he had broached the subject of marriage,—soon after her return to town,—but she had made it quite clear that this was a forbidden topic. The good comradeship ship and frankness of their intercourse had passed, and it seemed to his despairing lover's heart that it could never be regained. She carried her head a little higher; her smile was not the smile of old. He shrank from telling her that nothing mattered if she cared for him as he believed she did. She gave him no chance, for one thing, and he had never in his bitter self-communing found any words in which to tell her so. More than ever he needed Sylvia, but Sylvia had locked and barred the doors against him.

Mrs. Owen received them in her office, and the old lady's cheeriness was grateful to both of them.

"So you've been having supper with the Wares, have you, while I ate here all by myself? A nice way to treat a lone old woman,—leaving me to prop the 'Indiana Farmer' on the coffee pot for company! I had to stay at Lexington longer than I wanted to, and some of my Kentucky cousins held me up in Louisville. I notice, Daniel, that there are some doings at the State House. I must say it was a downright sin for old Ridgefield to go duck shooting at his time of life and die just when we were getting politics calmed down in this state. When I saw that old 'Stop, Look, Listen!' editorial printed like a Thanksgiving proclamation in the 'Courier,' I knew there was trouble. I must speak to Atwill. He's letting the automobile folks run the paper again."

She demanded to know when Dan would have time to do some work for her; she had disposed of her Kentucky farm and was going ahead with her scheme for a vocational school to be established at Waupegan. This was the first that Dan had heard of this project, and its bearing upon the hopes of the Bassetts as the heirs apparent of Mrs. Owen's estate startled him.

"I want you to draw up papers covering the whole business, Daniel, but you've got to get rid of your legislature first. I thought of a good name for the school, Sylvia. We'll call it Elizabeth House School, to hitch it on to the boarding-house. I want you and Daniel to go down East with me right after Christmas to look at some more schools where they do that kind of work. We'll have some fun next spring tearing up the farm and putting up the new buildings. Are Hallie and Marian in town, Sylvia?"

"No, they're at Fraserville," Sylvia replied. "And I had a note from Blackford yesterday. He's doing well at school now."

"Well, I guess you did that for him, Sylvia. I hope they're all grateful for that."

"Oh, it was nothing; and they paid me generously for my work."

"Humph!" Mrs. Owen sniffed. "Children, there are things in this world that a check don't settle."

There were some matters of business to be discussed. Dan had at last received an offer for the Kelton house at Montgomery, and Mrs. Owen thought he ought to be able to screw the price up a couple of hundred dollars.

"I'm all ready to close the estate when the sale is completed," said Dan. "Practically everything will be cleaned up when the house is sold. That Canneries stock that we inventoried as worthless is pretty sure to pan out. I've refused to compromise."

"That's right, Daniel. Don't you compromise that case. This skyrocket finance is all right for New York, but we can't allow it here in the country where folks are mostly square or trying to be."

"It seems hard to let the house go," said Sylvia. "It's given Mary a home and we'll have to find a place for her."

"Oh, that's all fixed," remarked Mrs. Owen. "I've got work for her at Elizabeth House. She can do the darning and mending. Daniel, have you brought the papers from Andrew's safety box over here?"

"Yes, Aunt Sally; I did that the last time I was in Montgomery. I wanted to examine the abstract of title and be ready to close this sale if you and Sylvia approved of it."

"Well, well," Mrs. Owen said, in one of those irrelevances that adorned her conversation.

Dan knew what was in her mind. Since that night on Waupegan, blessed forever by Sylvia's tears, the letter found among Professor Kelton's papers had led him through long, intricate mazes of speculation. It was the torn leaf from a book that was worthless without the context; a piece of valuable evidence, but inadmissible unless supported and illuminated by other testimony.

SYLVIA MUST KNOW JUST WHAT WE KNOW

Sylvia had been singularly silent, and Mrs. Owen's keen eyes saw that something was amiss. She stopped talking, as much as to say, "Now, if you young folks have anything troubling you, now's your time to come out with it."

An old clock on the stair landing boomed ten. Mrs. Owen stirred restlessly. Sylvia, sitting in a low chair by the fire, clasped her hands abruptly, clenched them hard, and spoke, turning her head slowly until her eyes rested upon Dan.

"Dan," she asked, "did you ever know—do you know now—what was in the letter you carried to Grandfather Kelton that first time I saw you—the time I went to find grandfather for you?"

Dan glanced quickly at Mrs. Owen.

"Answer Sylvia's question, Daniel," the old lady replied.

"Yes; I learned later what it was. And Aunt Sally knows."

"Tell me; tell me what you know about it," commanded Sylvia gravely, and her voice was clear now.

Dan hesitated. He rose and stood with his arm resting on the mantel.

"It's all right, Daniel. Now that Sylvia has asked, she must know just what we know," said Mrs. Owen.

"The letter was among your grandfather's papers. It was an offer to pay for your education. It was an unsigned letter."

"But you know who wrote it?" asked Sylvia, not lifting her head.

"No; I don't know that," he replied earnestly; "we haven't the slightest idea."

"But how did you come to be the messenger? Who gave you the letter?" she persisted quietly.

"Daniel never told me that, Sylvia. But if you want to know, he must tell you. It might be better for you not to know; you must consider that. It can make no difference now of any kind."

"It may make a difference," said Sylvia brokenly, not lifting her head; "it may make a great deal of difference. That's why I speak of it; that's why I must know!"

"Go on, Daniel; answer Sylvia's question."

"Mr. Fitch gave it to me. It had been entrusted to him for delivery by a personal friend or a client: I never knew. He assured me that he had no idea what the letter contained; but he knew of course where it came from. He chose me for the errand, I suppose, because I was a new man in the office, and a comparative stranger in town. I remember that he asked me if I had ever been in Montgomery, as though to be sure I had no acquaintances there. I carried back a verbal answer—which was stipulated in the letter. The answer was 'No,' and in what way Mr. Fitch passed it on to his client I never knew."

"You didn't tell me those things when we found the letter, Daniel," said Mrs. Owen reproachfully.

The old lady opened a drawer, found a chamois skin, and polished her glasses slowly. Dan walked away as though to escape from that figure with averted face crouching by the fire. But without moving Sylvia spoke again, with a monotonous level of tone, and her question had the empty ring of a lawyer's interrogatory worn threadbare by repetition to a succession of witnesses:—

"At that time was Mr. Bassett among the clients of Wright and Fitch, and did you ever see him in the office then, or at any time?"

Mrs. Owen closed the drawer deliberately and raised her eyes to Dan's affrighted gaze.

"Daniel, you'd better run along now. Sylvia's going to spend the night here."

Sylvia had not moved or spoken again when the outer door closed on Harwood.