VII

The Hopper, in his rôle of the Reversible Santa Claus, dropped off the car at the crossing Muriel had carefully described, waited for the car to vanish, and warily entered the Wilton estate through a gate set in the stone wall. The clouds of the early evening had passed and the stars marched through the heavens resplendently, proclaiming peace on earth and good-will toward men. They were almost oppressively brilliant, seen through the clear, cold atmosphere, and as The Hopper slipped from one big tree to another on his tangential course to the house, he fortified his courage by muttering, "They's things wot is an' things wot ain't!"—finding much comfort and stimulus in the phrase.

Arriving at the conservatory in due course, he found that Muriel's averments as to the vulnerability of that corner of her father's house were correct in every particular. He entered with ease, sniffed the warm, moist air, and, leaving the door slightly ajar, sought the pantry, lowered the shades, and, helping himself to a candle from a silver candelabrum, readily found the safe hidden away in one of the cupboards. He was surprised to find himself more nervous with the combination in his hand than on memorable occasions in the old days when he had broken into country postoffices and assaulted safes by force. In his haste he twice failed to give the proper turns, but the third time the knob caught, and in a moment the door swung open disclosing shelves filled with vases, bottles, bowls, and plates in bewildering variety. A chest of silver appealed to him distractingly as a much more tangible asset than the pottery, and he dizzily contemplated a jewel-case containing a diamond necklace with a pearl pendant. The moment was a critical one in The Hopper's eventful career. This dazzling prize was his for the taking, and he knew the operator of a fence in Chicago who would dispose of the necklace and make him a fair return. But visions of Muriel, the beautiful, the confiding, and of her little Shaver asleep on Humpy's bed, rose before him. He steeled his heart against temptation, drew his candle along the shelf and scrutinized the glazes. There could be no mistaking the red Lang-Yao whose brilliant tints kindled in the candle-glow. He lifted it tenderly, verifying the various points of Muriel's description, set it down on the floor and locked the safe.

He was retracing his steps toward the conservatory and had reached the main hall when the creaking of the stairsteps brought him up with a start. Some one was descending, slowly and cautiously. For a second time and with grateful appreciation of Muriel's forethought, he carefully avoided the ferocious jaws of the bear, noiselessly continued on to the conservatory, crept through the door, closed it, and then, crouching on the steps, awaited developments. The caution exercised by the person descending the stairway was not that of a householder who has been roused from slumber by a disquieting noise. The Hopper was keenly interested in this fact.

With his face against the glass he watched the actions of a tall, elderly man with a short, grayish beard, who wore a golf-cap pulled low on his head—points noted by The Hopper in the flashes of an electric lamp with which the gentleman was guiding himself. His face was clearly the original of a photograph The Hopper had seen on the table at Muriel's cottage—Mr. Wilton, Muriel's father, The Hopper surmised; but just why the owner of the establishment should be prowling about in this fashion taxed his speculative powers to the utmost. Warned by steps on the cement floor of the conservatory, he left the door in haste and flattened himself against the wall of the house some distance away and again awaited developments.

Wilton's figure was a blur in the star-light as he stepped out into the walk and started furtively across the grounds. His conduct greatly displeased The Hopper, as likely to interfere with the further carrying out of Muriel's instructions. The Lang-Yao jar was much too large to go into his pocket and not big enough to fit snugly under his arm, and as the walk was slippery he was beset by the fear that he might fall and smash this absurd thing that had caused so bitter an enmity between Shaver's grandfathers. The soft snow on the lawn gave him a surer footing and he crept after Wilton, who was carefully pursuing his way toward a house whose gables were faintly limned against the sky. This, according to Muriel's diagram, was the Talbot place. The Hopper greatly mistrusted conditions he didn't understand, and he was at a loss to account for Wilton's strange actions.

THE FAINT CLICK OF A LATCH MARKED THE PROWLER'S PROXIMITY TO A HEDGE

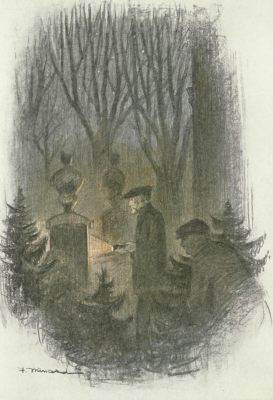

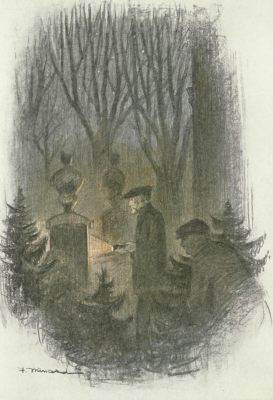

He lost sight of him for several minutes, then the faint click of a latch marked the prowler's proximity to a hedge that separated the two estates. The Hopper crept forward, found a gate through which Wilton had entered his neighbor's property, and stole after him. Wilton had been swallowed up by the deep shadow of the house, but The Hopper was aware, from an occasional scraping of feet, that he was still moving forward. He crawled over the snow until he reached a large tree whose boughs, sharply limned against the stars, brushed the eaves of the house.

The Hopper was aroused, tremendously aroused, by the unaccountable actions of Muriel's father. It flashed upon him that Wilton, in his deep hatred of his rival collector, was about to set fire to Talbot's house, and incendiarism was a crime which The Hopper, with all his moral obliquity, greatly abhorred.

Several minutes passed, a period of anxious waiting, and then a sound reached him which, to his keen professional sense, seemed singularly like the forcing of a window. The Hopper knew just how much pressure is necessary to the successful snapping back of a window catch, and Wilton had done the trick neatly and with a minimum amount of noise. The window thus assaulted was not, he now determined, the French window suggested by Muriel, but one opening on a terrace which ran along the front of the house. The Hopper heard the sash moving slowly in the frame. He reached the steps, deposited the jar in a pile of snow, and was soon peering into a room where Wilton's presence was advertised by the fitful flashing of his lamp in a far corner.

"He's beat me to ut!" muttered The Hopper, realizing that Muriel's father was indeed on burglary bent, his obvious purpose being to purloin, extract, and remove from its secret hiding-place the coveted plum-blossom vase. Muriel, in her longing for a Christmas of peace and happiness, had not reckoned with her father's passionate desire to possess the porcelain treasure—a desire which could hardly fail to cause scandal, if it did not land him behind prison bars.

This had not been in the programme, and The Hopper weighed judicially his further duty in the matter. Often as he had been the chief actor in daring robberies, he had never before enjoyed the high privilege of watching a rival's labors with complete detachment. Wilton must have known of the concealed cupboard whose panel fraudulently represented the works of Thomas Carlyle, the intent spectator reflected, just as Muriel had known, for though he used his lamp sparingly Wilton had found his way to it without difficulty.

The Hopper had no intention of permitting this monstrous larceny to be committed in contravention of his own rights in the premises, and he was considering the best method of wresting the vase from the hands of the insolent Wilton when events began to multiply with startling rapidity. The panel swung open and the thief's lamp flashed upon shelves of pottery.

At that moment a shout rose from somewhere in the house, and the library lights were thrown on, revealing Wilton before the shelves and their precious contents. A short, stout gentleman with a gleaming bald pate, clad in pajamas, dashed across the room, and with a yell of rage flung himself upon the intruder with a violence that bore them both to the floor.

"Roger! Roger!" bawled the smaller man, as he struggled with his adversary, who wriggled from under and rolled over upon Talbot, whose arms were clasped tightly about his neck. This embrace seemed likely to continue for some time, so tenaciously had the little man gripped his neighbor. The fat legs of the infuriated householder pawed the air as he hugged Wilton, who was now trying to free his head and gain a position of greater dignity. Occasionally, as opportunity offered, the little man yelled vociferously, and from remote recesses of the house came answering cries demanding information as to the nature and whereabouts of the disturbance.

The contestants addressed themselves vigorously to a spirited rough-and-tumble fight. Talbot, who was the more easily observed by reason of his shining pate and the pink stripes of his pajamas, appeared to be revolving about the person of his neighbor. Wilton, though taller, lacked the rotund Talbot's liveliness of attack.

An authoritative voice, which The Hopper attributed to Shaver's father, anxiously demanding what was the matter, terminated The Hopper's enjoyment of the struggle. Enough was the matter to satisfy The Hopper that a prolonged stay in the neighborhood might be highly detrimental to his future liberty. The combatants had rolled a considerable distance away from the shelves and were near a door leading into a room beyond. A young man in a bath-wrapper dashed upon the scene, and in his precipitate arrival upon the battle-field fell sprawling across the prone figures. The Hopper, suddenly inspired to deeds of prowess, crawled through the window, sprang past the three men, seized the blue-and-white vase which Wilton had separated from the rest of Talbot's treasures, and then with one hop gained the window. As he turned for a last look, a pistol cracked and he landed upon the terrace amid a shower of glass from a shattered pane.

A woman of unmistakable Celtic origin screamed murder from a third-story window. The thought of murder was disagreeable to The Hopper. Shaver's father had missed him by only the matter of a foot or two, and as he had no intention of offering himself again as a target he stood not upon the order of his going.

He effected a running pick-up of the Lang-Yao, and with this art treasure under one arm and the plum-blossom vase under the other, he sprinted for the highway, stumbling over shrubbery, bumping into a stone bench that all but caused disaster, and finally reached the road on which he continued his flight toward New Haven, followed by cries in many keys and a fusillade of pistol shots.

Arriving presently at a hamlet, where he paused for breath in the rear of a country store, he found a basket and a quantity of paper in which he carefully packed his loot. Over the top he spread some faded lettuce leaves and discarded carnations which communicated something of a blithe holiday air to his encumbrance. Elsewhere he found a bicycle under a shed, and while cycling over a snowy road in the dark, hampered by a basket containing pottery representative of the highest genius of the Orient, was not without its difficulties and dangers, The Hopper made rapid progress.

Halfway through New Haven he approached two policemen and slowed down to allay suspicion.

"Merry Chris'mas!" he called as he passed them and increased his weight upon the pedals.

The officers of the law, cheered as by a greeting from Santa Claus himself, responded with an equally hearty Merry Christmas.