CHAPTER XIV.

ROSE did not go down-stairs that night. She had a headache, which is the prescriptive right of a woman in trouble. She took the cup of tea which Agatha brought her, at the door of her room, and begged that mamma would not trouble to come to see her, as she was going to bed. She was afraid of another discussion, and shrank even from seeing any one. She had passed through a great many different moods of mind in respect to Mr. Incledon, but this one was different from all the rest. All the softening of feeling of which she had been conscious died out of her mind; his very name became intolerable to her. That which she had proposed to do, as the last sacrifice a girl could make for her family, an absolute renunciation of self and voluntary martyrdom for them, changed its character altogether when they no longer required it. Why should she do what was worse than death, when the object for which she was willing to die was no longer before her; when there was, indeed, no need for doing it at all? Would Iphigenia have died for her word’s sake, had there been no need for her sacrifice? and why should Rose do more than she? In this there was, the reader will perceive, a certain change of sentiment; for though Rose had made up her mind sadly and reluctantly to marry Mr. Incledon, yet she had not thought the alternative worse than death. She had felt while she did it the ennobling sense of having given up her own will to make others happy, and had even recognized the far-off and faint possibility that the happiness which she thus gave to others might, some time or other, rebound upon herself. But the moment her great inducement was removed, a flood of different sentiment came in. She began to hate Mr. Incledon, to feel that he had taken advantage of her circumstances, that her mother had taken advantage of her, that every one had used her as a tool to promote their own purpose, with no more consideration for her than had she been altogether without feeling. This thought went through her mind like a hot breath from a furnace, searing and scorching everything. And now that their purpose was served without her, she must still make this sacrifice—for honor! For honor! Perhaps it is true that women hold this motive more lightly than men, though indeed the honor that is involved in a promise of marriage does not seem to influence either sex very deeply in ordinary cases. I am afraid poor Rose did not feel its weight at all. She might be forced to keep her word, but her whole soul revolted against it. She had ceased to be sad and resigned. She was rebellious and indignant, and a hundred wild schemes and notions began to flit through her mind. To jump in such a crisis as this from the tender resignation of a martyr for love into the bitter and painful resistance of a domestic rebel who feels that no one loves her, is easy to the young mind in the unreality which more or less envelops everything to youth. From the one to the other was but a step. Yesterday she had been the centre of all the family plans, the foundation of comfort, the chief object of their thoughts. Now she was in reality only Rose the eldest daughter, who was about to make a brilliant marriage, and therefore was much in the foreground, but no more loved or noticed than any one else. In reality this change had actually come, but she imagined a still greater change; and fancy showed her to herself as the rebellious daughter, the one who had never fully done her duty, never been quite in sympathy with her mother, and whom all would be glad to get rid of, in marriage or any other way, as interfering with the harmony of the house. Such of us as have been young may remember how easy these revolutions of feeling were, and with what quick facility we could identify ourselves as almost adored or almost hated, as the foremost object of everybody’s regard or an intruder in everybody’s way. Rose passed a very miserable night, and the next day was, I think, more miserable still. Mrs. Damerel did not say a word to her on the subject which filled her thoughts, but told her that she had decided to go to London in the beginning of the next week, to look after the “things” which were necessary. As they were in mourning already, there was no more trouble of that description necessary on Uncle Ernest’s account, but only new congratulations to receive, which poured in on every side.

“I need not go through the form of condoling, for I know you did not have much intercourse with him, poor old gentleman,” one lady said; and another caught Rose by both hands and exclaimed on the good luck of the family in general.

“Blessings, like troubles, never come alone,” she said. “To think you should have a fortune tumbling down upon you on one side, and on the other this chit of a girl carrying off the best match in the country!”

“I hope we are sufficiently grateful for all the good things Providence sends us,” said Mrs. Damerel, fixing her eyes severely upon Rose.

Oh, if she had but had the courage to take up the glove thus thrown down to her! But she was not yet screwed up to that desperate pitch.

Mr. Incledon came later, and in his joy at seeing her was more lover-like than he had yet permitted himself to be.

“Why, I have not seen you since this good news came!” he cried, fondly kissing her in his delight and heartiness of congratulation, a thing he had never done before. Rose broke from him and rushed out of the room, white with fright and resentment.

“Oh, how dared he! how dared he!” she cried, rubbing the spot upon her cheek which his lips had touched with wild exaggeration of dismay.

And how angry Mrs. Damerel was! She went up-stairs after the girl, and spoke to her as Rose had never yet been spoken to in all her soft life—upbraiding her with her heartlessness, her disregard of other people’s feelings, her indifference to her own honor and pledged word. Once more Rose remained up-stairs, refusing to come down, and the house was aghast at the first quarrel which had ever disturbed its decorum.

Mr. Incledon went away bewildered and unhappy, not knowing whether to believe that this was a mere ebullition of temper, such as Rose had never shown before, which would have been a venial offence, rather amusing than otherwise to his indulgent fondness; or whether it meant something more, some surging upwards of the old reluctance to accept him, which he had believed himself to have overcome. This doubt chilled him to the heart, and gave him much to think of as he took his somewhat dreary walk home—for failure, after there has been an appearance of success, is more discouraging still than when there has been no opening at all in the clouded skies. And Agatha knocked at Rose’s locked door, and bade her good night through the keyhole with a mixture of horror and respect—horror for the wickedness, yet veneration for the courage which could venture thus to beard all constituted authorities. Mrs. Damerel herself said no good night to the rebel. She passed Rose’s door steadily without allowing herself to be led away by the impulse which tugged at her heart to go in and give the kiss of grace, notwithstanding the impenitent condition of the offender. Had the mother done this, I think all that followed might have been averted, and that Mrs. Damerel would have been able eventually to carry out her programme and arrange the girl’s life as she wished. But she thought it right to show her displeasure, though her heart almost failed her.

Rose had shut herself up in wild misery and passion. She had declared to herself that she wanted to see no one; that she would not open her door, nor subject herself over again to such reproaches as had been poured upon her. But yet when she heard her mother pass without even a word, all the springs of the girl’s being seemed to stand still. She could not believe it. Never before in all her life had such a terrible occurrence taken place. Last night, when she had gone to bed to escape remark, Mrs. Damerel had come in ere she went to her own room and asked after the pretended headache, and kissed her, and bade her keep quite still and be better to-morrow. Rose got up from where she was sitting, expecting her mother’s appeal and intending to resist, and went to the door and put her ear against it and listened. All was quiet. Mrs. Damerel had gone steadily along the corridor, had entered the rooms of the other children, and now shut her own door—sure signal that the day was over. When this inexorable sound met her ears, Rose crept back again to her seat and wept bitterly, with an aching and vacancy in her heart which it is beyond words to tell. It seemed to her that she was abandoned, cut off from the family love, thrown aside like a waif and stray, and that things would never be again as they had been. This terrible conclusion always comes in to aggravate the miseries of girls and boys. Things could never mend, never again be as they had been. She cried till she exhausted herself, till her head ached in dire reality, and she was sick and faint with misery and the sense of desolation; and then wild schemes and fancies came into her mind. She could not bear it—scarcely for those dark helpless hours of the night could she bear it—but must be still till daylight; then, poor forlorn child, cast off by every one, abandoned even by her mother, with no hope before her but this marriage, which she hated, and no prospect but wretchedness—then she made up her mind she would go away. She took out her little purse and found a few shillings in it, sufficient to carry her to the refuge which she had suddenly thought of. I think she would have liked to fly out of sight and ken and hide herself forever, or at least until all who had been unkind to her had broken their hearts about her, as she had read in novels of unhappy heroines doing. But she was too timid to take such a daring step, and she had no money, except the ten shillings in her poor little pretty purse, which was not meant to hold much. When she had made up her mind, as she thought, or to speak more truly, when she had been quite taken possession of by this wild purpose, she put a few necessaries into a bag to be ready for her flight, taking her little prayer-book last of all, which she kissed and cried over with a heart wrung with many pangs. Her father had given it her on the day she was nineteen—not a year since. Ah, why was not she with him, who always understood her, or why was not he here? He would never have driven her to such a step as this. He was kind, whatever any one might say of him. If he neglected some things, he was never hard upon any one—at least, never hard upon Rose—and he would have understood her now. With an anguish of sudden sorrow, mingled with all the previous misery in her heart, she kissed the little book and put it into her bag. Poor child! it was well for her that her imagination had that sad asylum at least to take refuge in, and that the rector had not lived long enough to show how hard in worldliness a soft and self-indulgent man can be.

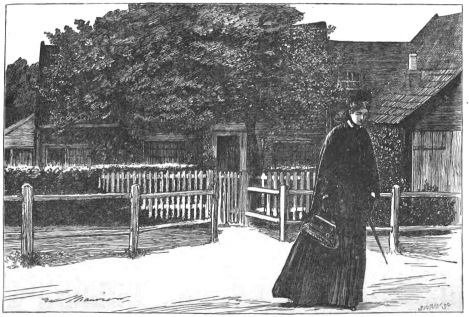

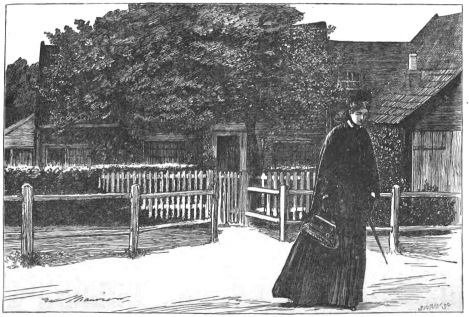

Rose did not go to bed. She had a short, uneasy sleep, against her will, in her chair—dropping into constrained and feverish slumber for an hour or so in the dead of the night. When she woke, the dawn was blue in the window, making the branches of the honeysuckle visible through the narrow panes. There was no sound in heaven or earth except the birds chirping, but the world seemed full of that; for all the domestic chat has to be got over in all the nests before men awake and drown the delicious babble in harsher commotions of their own. Rose got up and bathed her pale face and red eyes, and put on her hat. She was cold, and glad to draw a shawl round her and get some consolation and strength from its warmth; and then she took her bag in her hand, and opening her door, noiselessly stole out. There was a very early train which passed the Dingle station, two miles from Dinglefield, at about five o’clock, on its way to London; and Rose hoped, by being in time for that, to escape all pursuit. How strange it was, going out, like a thief into the house, all still and shut up, with its windows closely barred, the shutters up, and a still, unnatural half-light gleaming in through the crevices! As she stole down-stairs her very breathing, the sound of her own steps, frightened Rose; and when she looked in at the open door of the drawing-room and saw all the traces of last night’s peaceful occupations, a strange feeling that all the rest were dead and she a fugitive stealing guiltily away, came on her so strongly that she could scarcely convince herself it was not true. It was like the half-light that had been in all the rooms when her father lay dead in the house, and made her shiver. Feeling more and more like a thief, she opened the fastenings of the hall door, which were rusty and gave her some trouble. It was difficult to open them, still more difficult to close it softly without alarming the house; and this occupied her mind, so that she made the last step almost without thinking what she was doing. When she had succeeded in shutting the door, then it suddenly flashed upon her, rushed upon her like a flood—the consciousness of what she had done. She had left home, and all help and love and protection; and—Heaven help her!—here she was out of doors in the open-eyed day, which looked at her with a severe, pale calm—desolate and alone! She held by the pillars of the porch to support her for one dizzy, bewildered moment; but now was not the time to break down or let her terrors, her feelings overcome her. She had taken the decisive step and must go on now.

Mrs. Damerel, disturbed perhaps by the sound of the closing door, though she did not make out what it was, got up and looked out from the window in the early morning, and, at the end of the road which led to the Green, saw a solitary figure walking, which reminded her of Rose. She had half forgotten Rose’s perverseness, in her sleep, and I think the first thing that came into her mind had been rather the great deliverance sent to her in the shape of uncle Ernest’s fortune, than the naughtiness—though it was almost too serious to be called naughtiness—of her child. And though it struck her for the moment with some surprise to see the slim young figure on the road so early, and a passing notion crossed her mind that something in the walk and outline was like Rose, yet it never occurred to her to connect that unusual appearance with her daughter. She lay down again when she had opened the window, with a little half-wish, half-prayer, that Rose might “come to her senses” speedily. It was too early to get up and though Mrs. Damerel could not sleep, she had plenty to think about and this morning leisure was the best time for it. Rose prevailed largely among her subjects of thoughts, but did not fill her whole mind. She had so many other children, and so much to consider about them all!

Meanwhile Rose went on to the station, like a creature in a dream, feeling the very trees, the very birds watch her, and wondering that no faces peeped at her from the curtained cottage windows. How strange to think that all the people were asleep, while she walked along through the dreamy world, her footsteps filling it with strange echoes! How fast and soundly it slept, that world, though all the things out-of-doors were in full movement, interchanging their opinions, and taking council upon all their affairs! She had never been out, and had not very often been awake, at such an early hour, and the stillness from all human sounds and voices, combined with the wonderful fulness of the language of Nature, gave her a strange bewildered feeling, like that a traveller might have in some strange star or planet peopled with beings different from man. It seemed as if all the human inhabitants had resigned, and given up their places to another species. The fresh air which blew in her face, and the cheerful stir of the birds, recovered her a little from the fright with which she felt herself alone in that changed universe—and the sight of the first wayfarer making his way, like herself, towards the station, gave her a thrill of pain, reminding her that she was neither walking in a dream nor in another planet, but on the old-fashioned earth, dominated by men, and where she shrank from being seen or recognized. She put her veil down over her face as she stole in, once more feeling like a thief, at the wooden gate. Two or three people only, all of the working class, were kicking their heels on the little platform. Rose took her ticket with much trepidation, and stole into the quietest corner to await the arrival of the train. It came up at last with a great commotion, the one porter rushing to open the door of a carriage, out of which, Rose perceived quickly, a gentleman jumped, giving directions about some luggage. An arrival was a very rare event at so early an hour in the morning. Rose went forward timidly with her veil over her face to creep into the carriage which this traveller had vacated, and which seemed the only empty one. She had not looked at him, nor had she any curiosity about him. The porter, busy with the luggage, paid no attention to her, for which she was thankful, and she thought she was getting away quite unobserved, which gave her a little comfort. She had her foot on the step, and her hand on the carriage door, to get in.

SHE TOOK HER BAG IN HER HAND AND NOISELESSLY STOLE OUT.

“Miss Damerel!” cried an astonished voice close by her ear.

Rose’s foot failed on the step. She almost fell with the start she gave. Whose voice was it? a voice she knew—a voice somehow that went to her heart; but in the first shock she did not ask herself any questions about it, but felt only the distress and terror of being recognized. Then she decided that it was her best policy to steal into the carriage to escape questions. She did so, trembling with fright; but as she sat down in the corner, turned her face unwittingly towards the person, whoever it was, who had recognized her. He had left his luggage, and was gazing at her with his hand on the door. His face, all flushed with delight, gleamed upon her like sudden sunshine. “Miss Damerel!” he cried again, “you here at this hour?”

“Oh, hush! hush!” she cried, putting up her hand with instinctive warning. “I—don’t want to be seen.”

I am not sure that she knew him at the first glance. Poor child, her heart was too deeply preoccupied to do more than flutter feebly at the sight of him, and no secondary thought as to how he had come here, or what unlooked-for circumstance had brought him back, was within the range of her intelligence. Edward Wodehouse made no more than a momentary pause ere he decided what to do. He slipped a coin into the porter’s ready hand, and gave him directions about his luggage. “Keep it safe till I return; don’t send it home. I am obliged to go to town for an hour or two,” he said, and sprang again into the carriage he had just left. His heart was beating with no feeble flutter. He had the promptitude of a man who knows that no opportunity ought to be neglected. The door closed upon them with that familiar bang which we all know so well; the engine shrieked, the wheels jarred, and Rose Damerel and Edward Wodehouse—two people whom even the Imperial Government of England had been moved to separate—moved away into the distance, as if they had eloped with each other, sitting face to face.

Her heart fluttered feebly enough—his heart as strong as the pulsations of the steam-engine, and he thought almost as audible; but the first moment was one of embarrassment. “I cannot get over the wonder of this meeting,” he said. “Miss Damerel, what happy chance takes you to London this morning of all others? Some fairy must have done it for me?”

“No happy chance at all,” said Rose, shivering with painful emotion, and drawing her shawl closer round her. What could she say to him?—but she began to realize that it was him, which was the strangest, bewildering sensation. As for him, knowing of no mystery and no misery, the tender sympathy in his face grew deeper and deeper. Could it be poverty? could she be going to work like any other poor girl? A great throb of love and pity went through the young man’s heart.

“Don’t be angry with me,” he said; “but I cannot see you here, alone and looking sad—and take no interest. Can you tell me what it is? Can you make any use of me? Miss Damerel, don’t you know there is nothing in the world that would make me so happy as to be of service to you?”

“Have you just come home?” she asked.

“This morning; I was on my way from Portsmouth. And you—won’t you tell me something about yourself?”

Rose made a tremendous effort to go back to the ordinary regions of talk; and then she recollected all that had happened since he had been away. “You know that papa died,” she said, the tears springing to her eyes with an effort of nature which relieved her brain and heart.

“I heard that: I was very, very sorry.”

“And then for a time we were very poor; but now we are well off again by the death of mamma’s uncle Ernest; that is all, I think,” she said, with an attempt at a smile.

Then there was a pause. How was he to subject her to a cross-examination? and yet Edward felt that, unless something had gone very wrong, the girl would not have been here.

“You are going to town?” he said. “It is very early for you; and alone”—

“I do not mind,” said Rose; and then she added quickly, “when you go back, will you please not say you have seen me? I don’t want any one to know.”

“Miss Damerel, something has happened to make you unhappy?”

“Yes,” she said, “but never mind. It does not matter much to any one but me. Your mother is very well. Did she know that you were coming home?”

“No, it is quite sudden. I am promoted by the help of some kind unknown friend or another, and they could not refuse me a few days’ leave.”

“Mrs. Wodehouse will be very glad,” said Rose. She seemed to rouse out of her preoccupation to speak to him, and then fell back. The young sailor was at his wits’ end. What a strange coming home it was to him! He had dreamt of his first meeting with Rose in a hundred different ways, and rehearsed it, and all that he would say to her; but such a wonderful meeting as this had never occurred to him; and to have her entirely to himself, yet not to know what to say!

“There must be changes since I left. It will soon be a year ago,” he said, in sheer despair.

“I do not remember any changes,” said Rose, “except the rectory. We are in the White House now. Nothing else has happened that I know—yet.”

This little word made his blood run cold—yet. Did it mean that something was about to happen? He tried to overcome that impression by a return to the ground he was sure of. “May I speak of last year?” he said. “I went away very wretched—as wretched as any man could be.”

Rose was too far gone to think of the precautions with which such a conversation ought to be conducted. She knew what he meant, and why should she pretend she did not? Not that this reflection passed through her mind, which acted totally upon impulse, without any reflection at all.

“It was not my fault,” she said, simply. “I was alone with papa, and he would not let me go.”

“Ah!” he said, his eyes lighting up; “you did not think me presumptuous, then? you did not mean to crush me? Oh! if you knew how I have thought of it, and questioned myself! It has never been out of my mind for a day—for an hour”—

She put up her hand hastily. “I may be doing wrong,” she said, “but it would be more wrong still to let you speak. They would think it was for this I came away.”

“What is it? what is it?” he said; “something has happened. Why may not I tell you, when I have at last this blessed opportunity? Why is it wrong to let me speak?”

“They will think it was for this I came away,” said Rose. “Oh! Mr. Wodehouse, you should not have come with me. They will say I knew you were to be here. Even mamma, perhaps, will think so, for she does not think well of me, as papa used to do. She thinks I am selfish, and care only for my own pleasure,” said Rose with tears.

“You have come away without her knowledge?”

“Yes.”

“Then you are escaping from some one?” said Wodehouse, his face flushing over.

“Yes! yes.”

“Miss Damerel, come back with me. Nobody, I am sure, will force you to do anything. Your mother is too good to be unkind. Will you come back with me? Ah, you must not—you must not throw yourself upon the world; you do not know what it is,” said the young sailor, taking her hand, in his earnestness. “Rose—dear Rose—let me take you back.”

She drew her hand away from him, and dried the hot tears which scorched her eyes. “No, no,” she said. “You do not know, and I want nobody to know. You will not tell your mother, nor any one. Let me go, and let no one think of me any more.”

“As if that were possible!” he cried.

“Oh, yes, it is possible. I loved papa dearly; but I seldom think of him now. If I could die you would all forget me in a year. To be sure I cannot die; and even if I did, people might say that was selfish too. Yes, you don’t know what things mamma says. I have heard her speak as if it were selfish to die,—escaping from one’s duties; and I am escaping from my duties; but it can never, never be a duty to marry when you cannot—What am I saying?” said poor Rose. “My head is quite light, and I think I must be going crazy. You must not mind what I say.”