CHAPTER V.

ROSE grew very much better, almost quite well, next day. There was still a little thrill about her of the pain past, but in the mean time nothing had yet happened, no blank had been made in the circle of neighbors; and though she was still as sorry as ever, she said to herself, for poor Mrs. Wodehouse (which was the only reason she had ever given to herself for that serrement de cœur), yet there were evident consolations in that poor lady’s lot, if she could but see them. Edward would come back again; she would get letters from him; she would have him still, though he was away. She was his inalienably, whatever distance there might be between them. This seemed a strong argument to Rose in favor of a brighter view of the subject, though I do not think it would have assisted Mrs. Wodehouse; and, besides, there were still ten days, which—as a day is eternity to a child—was as good as a year at least to Rose. So she took comfort, and preened herself like a bird, and came again forth to the day in all her sweet bloom, her tears got rid of in the natural way, her eyes no longer hot and heavy. She scarcely observed even, or at least did not make any mental note of the fact, that she did not see Edward Wodehouse for some days thereafter. “How sorry I am to have missed them!” her mother said, on hearing that the young man and his mother had called in her absence; and Rose was sorry too, but honestly took the fact for an accident. During the ensuing days there was little doubt that an unusual amount of occupation poured upon her. She went with her father to town one morning to see the pictures in the exhibitions. Another day she was taken by the same delightful companion to the other side of the county to a garden party, which was the most beautiful vision of fine dresses and fine people Rose had ever seen. I cannot quite describe what the girl’s feelings were while she was going through these unexpected pleasures. She liked them, and was pleased and flattered; but at the same time a kind of giddy sense of something being done to her which she could not make out,—some force being put upon her, she could not tell what, or for why,—was in her mind. For the first time in her life she was jealous and curious, suspecting some unseen motive, though she could not tell what it might be.

On the fourth day her father and mother both together took her with them to Mr. Incledon’s, to see, they said, a new picture which he had just bought—a Perugino, or, it might be, an early Raphael. “He wants my opinion—and I want yours, Rose,” said her father, flattering, as he always did, his favorite child.

“And Mr. Incledon wants hers, too,” said Mrs. Damerel. “I don’t know what has made him think you a judge, Rose.”

“Oh! how can I give an opinion—what do I know?” said Rose, bewildered; but she was pleased, as what girl would not be pleased? To have her opinion prized was pleasant, even though she felt that it was a subject upon which she could pass no opinion. “I have never seen any but the Raphaels in the National Gallery,” she said, with alarmed youthful conscientiousness, as they went along, “and what can I know?”

“You can tell him if you like it; and that will please him as much as if you were the first art critic in England,” said the rector. These words gave Rose a little thrill of suspicion—for why should Mr. Incledon care for her opinion?—and perplexed her thoughts much as she walked up the leafy road to the gate of Whitton Park, which was Mr. Incledon’s grand house. Her father expatiated upon the beauty of the place as they went in; her mother looked preoccupied and anxious; and Rose herself grew more and more suspicious, though she was surprised into some exclamations of pleasure at the beauty and greenness of the park.

“I wonder I have never been here before,” she said; “how could it be? I thought we had been everywhere when we were children, the boys and I.”

“Mr. Incledon did not care for children’s visits,” said her mother.

“And he was in the right, my dear. Children have no eye for beauty; what they want is space to tumble about in, and trees to climb. This lovely bit of woodland would be lost on boys and girls. Be thankful you did not see it when you were incapable of appreciating it, Rose.”

“It is very odd, though,” she said. “Do you think it is nice of Mr. Incledon to shut up so pretty a place from his neighbors—from his friends?—for, as we have always lived so near, we are his friends, I suppose.”

“Undoubtedly,” said the rector; but his wife said nothing. I do not think her directer mind cared for this way of influencing her daughter. She was anxious for the same object, but she would have attained it in a different way.

Here, however, Mr. Incledon himself appeared with as much demonstration of delight to see them as was compatible with the supposed accidental character of the visit. Mr. Incledon was one of those men of whom you feel infallibly certain that they must have been “good,” even in their nurse’s arms. He was slim and tall, and looked younger than he really was. He had a good expression, dark eyes, and his features, though not at all remarkable, were good enough to give him the general aspect of a handsome man. Whether he was strictly handsome or not was a frequent subject of discussion on the Green, where unpleasant things had been said about his chin and his eyebrows, but where the majority was distinctly in his favor. His face was long, his complexion rather dark, and his general appearance “interesting.” Nobody that I know of had ever called him commonplace. He was interesting—a word which often stands high in the rank of descriptive adjectives. He was the sort of man of whom imaginative persons might suppose that he had been the hero of a story. Indeed, there were many theories on the subject; and ingenious observers, chiefly ladies, found a great many symptoms of this in his appearance and demeanor, and concluded that a man so well off and so well looking would not have remained unmarried so long had there not been some reason for it. But this phase of his existence was over, so far as his own will was concerned. If he had ever had any reason for remaining unmarried, that obstacle must have been removed; for he was now anxious to marry, and had fully made up his mind to do so at as early a date as possible. I do not know whether it could be truly said that he was what foolish young people call “very much in love” with Rose Damerel; but he had decided that she was the wife for him, and meant to spare neither pains nor patience in winning her. He had haunted the rectory for some time, with a readiness to accept all invitations which was entirely unlike his former habits; for up to the time when he had seen and made up his mind about Rose, Mr. Incledon had been almost a recluse, appearing little in the tranquil society of the Green, spending much of his time abroad, and when at home holding only a reserved and distant intercourse with his neighbors. He gave them a handsome heavy dinner two or three times a year, and accepted the solemn return which society requires; but no one at Dinglefield had seen more of his house than the reception-rooms, or of himself than those grave festivities exhibited. The change upon him now was marked enough to enlighten the most careless looker-on; and the Perugino, which they were invited to see, was in fact a pretence which the rector and his wife saw through very easily, to make them acquainted with his handsome house and all its advantages. He took them all over it, and showed the glory of it with mingled complacency and submission to their opinion. Rose had never been within its walls before. She had never sat down familiarly in rooms so splendid. The master of the house had given himself up to furniture and decorations as only a rich man can do; and the subdued grace of everything about them, the wealth of artistic ornament, the size and space which always impress people who are accustomed to small houses, had no inconsiderable effect, at least upon the ladies of the party. Mr. Damerel was not awed, but he enjoyed the largeness and the luxury with the satisfaction of a man who felt himself in his right sphere; and Mr. Incledon showed himself, as well as his house, at his best, and, conscious that he was doing so, looked, Mrs. Damerel thought, younger, handsomer, and more attractive than he had ever looked before. Rose felt it, too, vaguely. She felt that she was herself somehow the centre of all—the centre, perhaps, of a plot, the nature of which perplexed and confused her; but the plot was not yet sufficiently advanced to give her any strong sensation of discomfort or fear. All that it did up to the present moment was to convey that sense of importance and pleasant consciousness of being the first and most flatteringly considered, which is always sweet to youth. Thus they were all pleased, and, being pleased, became more and more pleasant to each other. Rose, I think, forgot poor Mrs. Wodehouse altogether for the moment, and was as gay as if she had never been sad.

The house was a handsome house, raised on a slightly higher elevation than the rectory, surrounded by a pretty though not very extensive park, and commanding the same landscape as that which it was the pride of the Damerels to possess from their windows. It was the same, but with a difference; or, rather, it was like a view of the same subject painted by a different artist, dashed in in bolder lines, with heavier massing of foliage, and one broad reach of the river giving a great centre of light and shadow, instead of the dreamy revelations here and there of the winding water as seen from the rectory. Rose gave an involuntary cry of delight when she was taken out to the green terrace before the house, and first saw the landscape from it, though she never would confess afterwards that she liked it half so well as the shadowy distance and softer, sweep of country visible from her old home. Mr. Incledon was as grateful to her for her admiration as if the Thames and the trees had been of his making and ventured to draw near confidentially and say how much he hoped she would like his Perugino—or, perhaps, Raphael. “You must give me your opinion frankly,” he said.

“But I never saw any Raphaels except those in the National Gallery,” said Rose, blushing with pleasure, and shamefacedness, and conscientious difficulty. It did not occur to the girl that her opinion could be thus gravely asked for by a man fully aware of its complete worthlessness as criticism. She thought he must have formed some mistaken idea of her knowledge or power. “And I don’t—love them—very much,” she added, with a little hesitation and a deeper blush, feeling that his momentary good opinion of her must now perish forever.

“What does that mean?” said Mr. Incledon. He was walking on with her through, as she thought, an interminable vista of rooms, one opening into the other, towards the shrine in which he had placed his picture. “There is something more in it than meets the ear. It does not mean that you don’t like them”—

“It means—that I love the photograph of the San Sisto, that papa gave me on my birthday,” said Rose.

“Ah! I perceive; you are a young critic to judge so closely. We have nothing like that, have we? How I should like to show you the San Sisto picture! Photographs and engravings give no idea of the original.”

“Oh, please don’t say so!” said Rose, “for so many people never can see the original. I wish I might some time. The pictures in the National Gallery do not give me at all the same feeling; and, of course, never having seen but these, I cannot be a judge; indeed, I should not dare to say anything at all. Ah, ah!”

Rose stopped and put her hands together, as she suddenly perceived before her, hung upon a modest gray-green wall with no other ornament near, one of those very youthful, heavenly faces, surrounded by tints as softly bright as their own looks, which belong to that place and period in which Perugino taught and Raphael learned—an ineffable sweet ideal of holiness, tenderness, simplicity, and youth. The girl stood motionless, subdued by it, conscious of nothing but the picture. It was doubly framed by the doorway of the little room in which it kept court. Before even she entered that sacred chamber, the young worshipper was struck dumb with adoration. The doorway was hung with silken curtains of the same gray-green as the wall, and there was not visible, either in this soft surrounding framework, or in the picture itself, any impertinent accessory to distract the attention. The face so tenderly abstract, so heavenly human, looked at Rose as at the world, but with a deeper, stronger appeal; for was not Mary such a one as she? The girl could not explain the emotion which seized her. She felt disposed to kneel dawn, and she felt disposed to weep, but did neither; only stood there, with her lips apart, her eyes abstract yet wistful, like those in the picture; and her soft hands clasped and held unconsciously, with that dramatic instinct common to all emotion, somewhere near her heart.

“You have said something,” said Mr. Incledon, softly, in her ear, “more eloquent than I ever heard before. I am satisfied that it is a Raphael now.”

“Why?” said Rose, awakening with great surprise out of her momentary trance, and shrinking back, her face covered with blushes, to let the others pass who were behind. He did not answer her except by a look, which troubled the poor girl mightily, suddenly revealing to her the meaning of it all. When the rest of the party went into the room, Rose shrank behind her mother, cowed and ashamed, and instead of looking at the picture, stole aside to the window and looked out mechanically to conceal her troubled countenance. As it happened, the first spot on which her eye fell was the little cottage at Ankermead, upon which just the other evening she had looked with Edward Wodehouse. All he said came back to her, and the evening scene in which he said it, and the soft, indescribable happiness and sweetness that had dropped upon her like the falling dew. Rose had not time to make any question with herself as to what it meant; but her heart jumped up in her bosom and began to beat, and a sudden, momentary perception of how it all was flashed over her. Such gleams of consciousness come and go when the soul is making its first experiences of life. For one second she seemed to see everything clearly as a landscape is seen when the sun suddenly breaks out; and then the light disappeared, and the clouds re-descended, and all was blurred again. Nevertheless, this strange, momentary revelation agitated Rose almost more than anything that had ever happened to her before; and everything that was said after it came to her with a muffled sound, as we hear voices in a dream. A longing to get home and to be able to think took possession of her. This seemed for the moment the thing she most wanted in the world.

“If ever I have a wife,” Mr. Incledon said, some time after, “this shall be her boudoir. I have always intended so; unless, indeed, she is perverse as my mother was, who disliked this side of the house altogether, and chose rooms which looked out on nothing but the park and the trees.”

THE GIRL STOOD MOTIONLESS, SUBDUED BY IT.

“I hope, as everything is ready for her, the lady will soon appear,” said Mrs. Damerel; while poor little Rose suddenly felt her heart stop in its beating, and flutter and grow faint.

“Ah!” said Incledon, shaking his head, “it is easier to gild the cage than to secure the bird.”

How glad she was when they were out again in the open air, walking home! How delightful it was to be going home, to get off this dangerous ground, to feel that there was a safe corner to fly to! Nobody said anything to her, fortunately for Rose, but let her walk off her excitement and the flutter of terror and dismay which had come over her. “Easier to gild the cage than to secure the bird.” The poor little bird felt already as if she had been caught in some snare; as if the fowler had got his hand upon her, and all her flutterings would be of no avail. How little she had thought that this was what was meant by their flattering eagerness to have her opinion about the Perugino! She kept close to her mother till they got safely out of the park, for Mr. Incledon attended them as far as the gates, and Rose was so much startled that she did not feel safe near him. It seemed to her that the plot must be brought to perfection at once, and that there was no escape except in keeping as far off as possible. She resolved to herself as she went along that she would never approach him if she could help it, or let him speak to her. Her sensations were something like those with which a startled hare might, I suppose, contemplate from beneath her couch of fern the huntsman gathering the hounds which were to run her down. Rose had no sense of satisfaction such as an older woman might have felt, in the love of so important a personage as Mr. Incledon. She was neither flattered nor tempted by the thought of all the good things she might have at her disposal as his wife—his beautiful house, his wealth, his consequence, even his Perugino, though that had drawn the very heart out of her breast—none of these things moved her. She was neither proud of his choice, nor dazzled by his wealth. She was simply frightened, neither more nor less—dead frightened, and eager to escape forever out of his way.

It was now afternoon, the most languid hour of the day, and the village roads were very hot, blazing, and dusty, after the soft shade of Whitton Park. Mr. Damerel, who was not much of a pedestrian, and hated dust, and abhorred all the irritations and weariness of excessive heat, came along somewhat slowly, skirting the houses to get every scrap of shade which was possible. They were thus quite close to a row of cottages when Mr. Nolan came out from the door of one so suddenly as almost to stumble over his rector.

“Just like a shot from a cannon is an Irishman’s exit from a visit,” said Mr. Damerel, peevishly, though playfully. “Nolan, you salamander, you who never feel the heat, you may at least have some pity upon me.”

“You are the very man I want,” said the curate, whose brow was clouded with care. “The poor creature’s dying. You’ll go and say a word to her? I was going to your house, wondering would I find ye? and lo! Providence puts ye here.”

“I hope I shall feel as much obliged to Providence as you do,” said the rector still more peevishly. “What is it? Who is it? What do you want?”

“Sure it’s only a poor creature dying—nothing to speak about in this dreary world” said good Mr. Nolan; “but she has a fancy to see you. I have done all I could to pacify her; but she says she knew you in her better days.”

“It is old Susan Aikin,” said Mrs. Damerel, in answer to her husband’s inquiring look. “She has always wanted to see you; but what good could you do her? and she has had a bad fever, and it is a miserable place.”

“Not that you’ll think twice of that,” said Nolan hurriedly, “when it’s to give a bit of comfort to a dying creature that longs to see you;” though indeed it would puzzle the world to tell why, he added in his heart.

“Certainly not,” said the rector—a quantity of fine wrinkles, unseen on ordinary occasions, suddenly appearing like a net-work on his forehead. His voice took a slightly querulous tone, in spite of the readiness with which he replied. “You need not wait,” he said, turning to his wife and daughter. “Go on gently, and perhaps I may overtake you if it is nothing important. What is it, Nolan; a case of troubled conscience? Something on her mind?”

“Nothing but a dyin’ fancy,” said Mr. Nolan. “She’s harped on it these three days. No, she’s a good soul enough; there’s no story to tell; and all her duties done, and life closing as it ought. It’s but a whim; but they will all take it as a great favor,” said the curate, seeing that his superior officer looked very much in the mind to turn and fly.

“A whim,” he said, querulously. “You know I am not careless of other people’s feelings—far from it, I hope; but my own organization is peculiar, and to undergo this misery for a whim—you said a whim”—

“But the creature’s dying!”

“Pah! what has dying to do with it? Death is a natural accident. It is not meritorious to die, or a thing to which every other interest should yield and bow. But, never mind,” the rector added, after this little outbreak; “it is not your fault—come, I’ll go.”

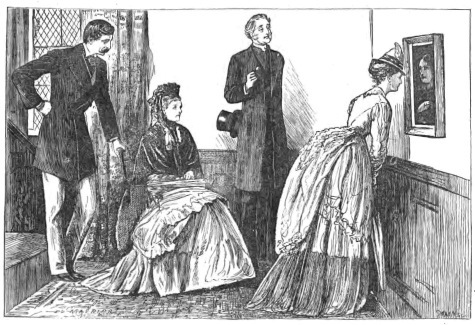

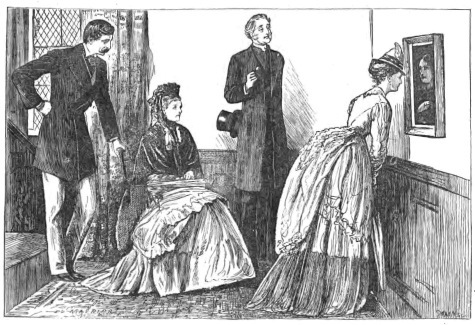

Rose and her mother had lingered to hear the end of the discussion; and just as the rector yielded thus, and, putting as good a grace as possible on the unwillingly performed duty, entered, led by Mr. Nolan, the poor little cottage, the ladies were joined by Mrs. Wodehouse and her son, who had hurried up at sight of them. Mrs. Wodehouse had that reserved and solemn air which is usual to ladies who are somewhat out of temper with their friends. She was offended, and she meant to show it. She said “Good morning” to Mrs. Damerel, instead of “How do you do?” and spoke with melancholy grandeur of the weather, and the extreme heat, and how a thunderstorm must be on its way. They stood talking on these interesting topics, while Rose and Edward found themselves together. It seemed to Rose as if she was seeing him for the first time after a long absence or some great event. The color rushed to her face in an overwhelming flood, and a tide of emotions as warm, as tumultuous, as bewildering, rushed into her heart. She scarcely ventured to lift her eyes when she spoke to him. It seemed to her that she understood now every glance he gave her, every tone of his voice.

“I almost feared we were not to meet again,” he said hurriedly; “and these last days run through one’s fingers so fast. Are you going out to-night?”

“I do not think so,” said Rose, half afraid to pledge herself, and still more afraid lest her mother should hear and interpose, saying, “Yes, they were engaged.”

“Then let me come to-night. I have only four days more. You will not refuse to bid a poor sailor good-by, Miss Damerel? You will not let them shut me out to-night?”

“No one can wish to shut you out,” said Rose, raising her eyes to his face for one brief second.

I do not think Edward Wodehouse was so handsome as Mr. Incledon. His manners were not nearly so perfect; he could not have stood comparison with him in any respect except youth, in which he had the better of his rival; but oh, how different he seemed to Rose! She could not look full at him; only cast a momentary glance at his honest, eager eyes; his face, which glowed and shone with meaning. And now she knew what the meaning was.

“So long as you don’t!” he said, eagerly, yet below his breath; and just at this moment Mrs. Damerel put forth her hand and took her daughter by the arm.

“We have had a long walk, and I am tired,” she said. “We have been to Whitton to see a new picture, and Mr. Incledon has so many beautiful things. Come, Rose. Mr. Wodehouse, I hope we shall see you before you go away.”

“Oh, yes, I hope so,” the young sailor faltered, feeling himself suddenly cast down from heaven to earth. He said nothing to her about that evening, but I suppose Mrs. Damerel’s ears were quick enough to hear the important appointment that had been made.

“My dear Rose, girls do not give invitations to young men, nor make appointments with them, generally, in that way.”

“I, mamma?”

“Don’t be frightened. I am not blaming you. It was merely an accident; but, my dear, it was not the right kind of thing to do.”

“Must I not speak to Mr. Wodehouse?” she asked, half tremblingly, half (as she meant it) satirically. But poor Rose’s little effusion of (what she intended for) gall took no effect whatever. Mrs. Damerel did not perceive that any satire was meant.

“Oh, you may speak to him! You may bid him good-by, certainly; but I—your papa—in short, we have heard something of Mr. Wodehouse which—we do not quite like. I do not wish for any more intimacy with them, especially just now.”

“Do you mean you have heard some harm of him?” said Rose, opening her eyes with a sudden start.

“Well, perhaps not any harm; I cannot quite tell what it was; but something which made your papa decide—in short, I don’t want to take too much notice of the Wodehouses as a family. They do not suit your papa.”

Rose walked on with her mother to the rectory gate, silent, with her heart swelling full. She did not believe that her father had anything to do with it. It was not he who was to blame, whatever Mrs. Damerel might say.