CHAPTER VI

SECRET SERVICE

THREE days of steady steaming brought the “Connecticut” within the tropics.

The sea was as peaceful as the waters of a lake and the sun overhead shone down with pitiless severity.

“All hands” were now dressed in white uniforms, which made them comfortable enough on deck under the cool shade of an awning, but below decks the heat from the engines and boilers was stifling.

The two friends spent most of their leisure hours in the open air and at night rolled themselves in their blankets on the clean white deck.

One evening they had made themselves comfortable for the night and were both speculating upon what was in store for them in the land of turmoil to which they were journeying.

“Did you notice the sailorman,” asked Sydney, “who has been walking past here as if he were trying to find out who we are?”

“I didn’t notice,” replied Phil sleepily; “it’s probably one of the messengers searching for some officer who is avoiding the heat as we are doing by sleeping on deck.”

“Maybe so,” Sydney answered, “but it appeared to me he scrutinized us very closely, although he must have seen immediately who we were. That light behind us makes us plainly visible.”

“We are accustomed to the darkness,” answered Phil, with a yawn, “while he has probably just come out of the light.”

Sydney was not at all satisfied with the explanation and would have continued the argument, but Phil’s even breathing showed his companion was perfectly satisfied with the solution.

They had been asleep but a short time when one of the heavy tropical rain-storms, which seem to be ever present on the horizon in these waters, burst upon the ship, surprising the boys, who had not noticed the gathering clouds earlier in the night. They saw with regret that they must seek other shelter or else sleep the remainder of the night below in their heated stateroom.

“I am going below, Syd. I am sleepy enough to sleep even in the heat,” said Phil, gathering his bedding and disappearing down the hatchway.

He groped his way across the dark passageway, sleepily feeling for the door of his stateroom.

Suddenly he collided heavily with a figure which sent him reeling across the deck. His hand struck the side of the bulkhead and he saved himself a fall.

In the dark he could just distinguish a white figure as it dashed through the door of the mess room and disappeared under the multitude of sleeping-hammocks on the berth deck.

What could it mean? What was this man doing in his room?

Sydney came in after Phil had turned on the light and was told of the experience.

“See if any of your valuables are missing?” he suggested. “Mine are here on the bureau all in plain sight.”

Phil had been rummaging through his desk. He now turned a smiling face to Sydney.

“You were right, Syd,” he laughed, “the locket is gone. He did risk detection to gain possession of it. But it doesn’t matter, I can never forget the girl’s face. I have looked at it a hundred times in the last few days.”

“The man of the locket and the fellow who was watching us on deck are one and the same,” Sydney exclaimed, proud of his perception.

“Probably so,” answered Phil, “but that doesn’t help us; he was clever enough not to be recognized.”

The boys, in spite of the incident, soon fell asleep, and when they awakened the “Connecticut” had anchored inside the break-water at La Boca.

It was but a short time after sunrise when they stood together at the rail gazing intently on their surroundings.

“So this is South America,” said Sydney finally; “it looks just like any other country, doesn’t it?”

“Yes, but there is a difference,” answered Phil, meditatively; “for instance, see that native boatman sculling along as if he had a week to reach his destination; then look over there at the coal pile on the mole. There are nearly enough men to actually eat the coal, yet they are not doing as much work as ten good Americans. We are in the land of ‘Mañana’ (to-morrow). No one wishes to work too hard to-day, for he wishes to save enough to do to-morrow.”

“We are not the first nation to send a war-ship here, I see,” said Captain Taylor, joining the boys in their study of the harbor. “There is a German cruiser over yonder and a Frenchman is anchored just astern of us, and our wireless operator has been in communication with a British ship for some hours. She is on her way from Barbadoes. It seems we are to have an interesting time.”

Phil was impatient to ask the captain when their work would commence, but he desisted. It were better the captain should broach the subject.

“I hope you lads have the ‘lingo’ at your tongue’s tip,” the captain remarked smilingly. “You won’t find much English spoken here, and a little Spanish is a necessity.”

“Yes, sir,” they both agreed.

Phil could not contain himself longer.

“When can we start on our work, sir?” he asked.

“Such zeal I have never seen before,” answered the captain, a merry twinkle in his eyes. “Soon enough, lad,” he added gravely. “I hope nothing happens to you youngsters. I almost fear I am wrong in not sending older and maybe wiser heads to do this work.”

“Oh, no, sir,” Phil and Sydney cried together; then Phil added, “We are old enough, sir; we are nearly twenty.”

“Nearly twenty,” roared the skipper in merriment. “You are both mere infants in the wicked ways of these people here, but it will be an excellent lesson for you. When I was your age,” he added, “it was during the Civil War, many times I did work that in these days of peace never comes to men of your age.”

The captain left them to receive the foreign officers who were coming alongside to pay the customary visit of courtesy to a senior commanding officer.

Some hours later Phil and Sydney received orders to prepare themselves to accompany Captain Taylor ashore to pay his respects to the United States Minister to Verazala.

As they left the ship in the speedy “Vidette,” our lads felt that a new and interesting life was opening before them. Were they not to have a hand in the affairs of their great nation?

They found the minister’s carriage awaiting them at the landing, and were driven rapidly amid staring crowds of natives through the narrow streets of the city.

The carriage drew up at a large house on a hill overlooking the harbor. The coat of arms, emblazoned on the door, was enough evidence that inside was the inviolable territory of the United States of America.

“Ah, captain,” cried the Honorable Robert Henderson, as he grasped the hands of the three officers in turn, “your fine ship carrying that grand old flag was a welcome sight when we awoke this morning. A great weight has been lifted from my mind.”

“We came down at full speed, sir,” replied Captain Taylor, courteously, “and now we are at your service, every man of us. You have but to command me.”

The old diplomat swallowed a lump in his throat before replying.

“Captain Taylor, you cannot imagine the delight it gives us exiles to feel that we have so many brave American hearts so near at hand. I pray there will be no need to resort to force, but affairs appear to be more serious than I should wish. The rebel army is but a league from the city, and awaits an opportunity to attack. Their leader, General Ruiz, is a cutthroat and unfit for the high office of president of the republic. My most trustworthy informant tells me the rebels are losing strength daily and so I have informed the State Department, but affairs lately have led me to believe that their strength has been underestimated. I should greatly deplore the city being taken by these brigands, for I fear much valuable property will be destroyed by their undisciplined followers.”

“There seems nothing for us to do, save await developments?” asked the captain, having followed closely the minister’s explanation of the situation.

“No, there is nothing,” he answered promptly. “I have a faithful vice-consul, who keeps me well informed of the movements on both sides. He is a naturalized American citizen. His name is Isidro Juarez. He has lived here many years and seems to have friends in both armies. I trust him implicitly. I shall keep you daily informed so that we may act promptly in an emergency.”

“Does the minister know that arms for the insurgents are coming from the United States?” asked Phil of the captain as they drove back to the boat landing.

“He made no mention of it,” he answered. “If his information is really trustworthy, he must know it.”

On arriving on board ship, Phil was called upon to make a boarding call to the American mail steamer, just arrived from New York.

Buckling on his sword, the badge of official duty, he descended the gangway. As he was about to step into the “Vidette” alongside, he glanced up and saw O’Neil was at the helm.

“Well,” he cried with pleasure, “so you have had a promotion too; I am mighty glad to see you in my boat. This is going to be my boat while here,” he confided in a lower tone, “and I know of no one whom I would rather have than you, O’Neil.”

The coxswain beamed with pleasure.

“Thank you, Mr. Perry,” he answered abashed. “It’s a great honor you are paying me, sir.”

After getting alongside the anchored merchantman, Phil mounted the gangway ladder to the main deck.

There he was received cordially by her captain.

“Glad to be acquainted with you,” he said, shaking the lad’s hand. “It does me good to see our fine big ships in foreign ports. These dagos here are a hundred per cent. more civil already.”

He led the way to his cabin and gave Phil the information which the custom of the naval service requires be obtained upon visiting American merchantmen in foreign ports.

“No, you cannot be of any assistance to me,” answered the captain to Phil’s inquiry; “but it’s great to see her over there. Why, she could blow this whole town into pieces in a half hour, and she would, too, if it were necessary, wouldn’t she?” the captain interrogated, warmed to his theme.

A uniformed official appeared at this moment to speak to him.

“Come in, Baldwin. This is a young officer from the battle-ship,” the captain announced; “Mr. Baldwin is our purser.”

“The legation steam launch is alongside for the minister’s freight,” the purser reported. “Mr. Juarez is in her to sign the receipts for the bills of lading. Shall I deliver it at once? There are about twenty heavy packages.”

“Very well, Baldwin, go right ahead,” replied the captain. Then turning to Phil, as the purser withdrew: “A diplomatic officer has a privilege which no one else has; his freight can be landed direct; everything else must go through the custom-house ashore and be inspected.”

The captain excused himself shortly but insisted that Phil should make himself at home.

“Take a look about the ship,” he said proudly; “she’s not as big as yours yonder, but she is a stanch one for this trade.”

Phil was glad to have an excuse to remain. He had heard something to arouse his curiosity.

“I shall have a look at this Juarez and his boxes,” he mused as he followed the captain on deck.

Stepping to the high rail, he glanced down on a large launch, lying alongside the ship abreast her forward cargo hatch. Big boxes were being hoisted out of the hold by the ship’s derrick and landed on the smaller vessel’s deck. Phil saw a short heavily built man, dressed in white clothes, with a wide brimmed panama set over a massive head. He was superintending the landing of the boxes.

This man Phil knew must be Juarez, the minister’s confidential vice-consul.

Phil descended to the lower deck in order to be nearer the work of landing the cargo. He also wanted to have a better look at this man.

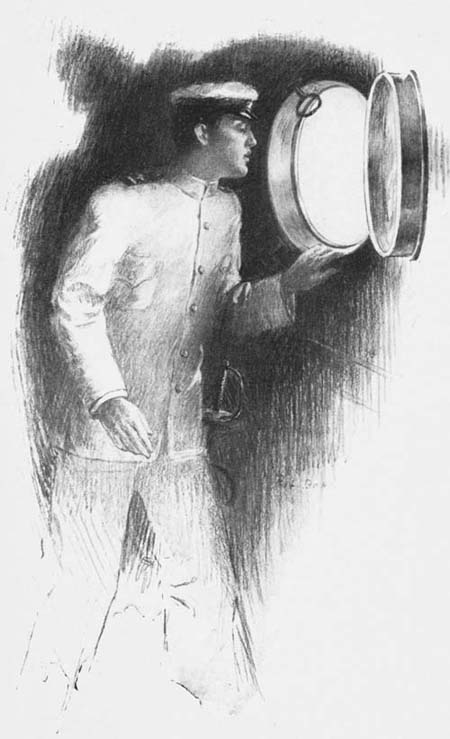

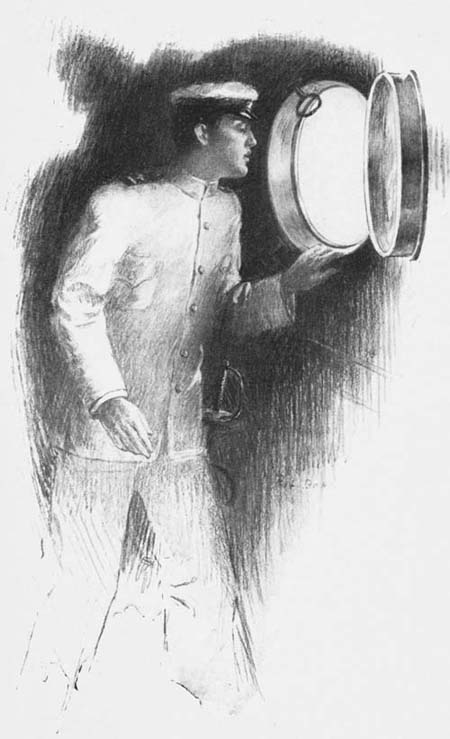

He found a convenient air port not ten feet from the launch, where he could see unobserved by those on board it.

There were a number of very heavy packages and the small natives on the deck of the launch strained and pulled to find deck space for them all.

HE FOUND A CONVENIENT

AIR PORT

Phil saw a small native fishing-boat, her sail flapping idly in the gentle breeze, move slowly and with deliberation over the tranquil water, edging in toward the launch.

The vice-consul seemed not to observe it, but Phil saw the eagerness on the fisherman’s face. He watched the scene with rising pulse.

The boat drifted foot by foot to within ten feet of the launch.

Juarez busied himself at the strap of a large box in the stern of the launch nearest the fisherman.

Phil saw the fisherman make a swift move with his hand, and saw a white object fall on the launch’s deck at Juarez’s feet. Juarez lifted one foot carelessly and placed it fairly on the object.

The fisherman put his helm over and hauled taut his sheet. The sails quickly filled and the boat glided swiftly toward the harbor’s mouth.

Juarez stooped down and rising, thrust his hands in his pockets.

Phil felt every nerve thrill. His secret service had begun under a lucky star.