CHAPTER IV

STIRRING UP TROUBLE

“I’D like to have seen the garden fête.” The speaker arose from his seat at a desk, pushed a mass of papers aside and glanced at his watch.

“By Jove, it’s nearly over,” he added in some surprise. He put his watch back in his pocket, and took a coat and hat from a peg in the corner. “There’s my stuff on the desk. I am ashamed to be the author of it.

“Jim, I think I’ll go around and take a look at these naval officers I’ve been maligning. They’ll be coming away from the party just about the time I get there, and I’ve a card of admission here in my pocket.

“Hello! this is your coat. Why on earth don’t you have the lining sewed up? You’ll be losing something out of it before long if you don’t.”

George Randall, newspaper correspondent, hung up the other’s coat and took his own, putting it on thoughtfully.

“Jim, you haven’t any business sticking to such an uncertain game as this,” he added, a note of sympathy in his voice. “You’ve a family, and ought to be home earning honest money.”

The man addressed, probably twenty years older than the speaker, laughed uneasily.

“I was attracted by the price, the same as you were, George,” he replied regretfully. “Neither of us understood what would be expected of us, and if we weren’t so hard up we wouldn’t have accepted. But we are in it now, and there’s no turning back.”

“Some one of these mornings,” Randall said gravely, “we’re going to wake up to find we’ve been caught, and I’d hate to think what the Japs will do to us. Boil us in oil, probably. That used to be the favorite punishment for high treason in the days of the late Shoguns.

“I am frightened at Impey’s methods,” he added. “He’s playing a dangerous game, and now with this American cruiser in port he’ll have to be doubly careful.”

“Well, as long as he keeps that turbine yacht in Yokohama harbor my mind will be easy,” James Wells exclaimed, smiling at his companion’s earnestness. “The Japs don’t know that she has the speed of a torpedo boat.”

Randall’s hand was on the door-knob, but suddenly he seemed to change his mind, and walked back to where his companion was standing.

“I feel like a cur, writing the things I do when I know they are all untrue.” His voice was vehement and his young face wore a troubled look. “There’s only a filmy web of truth for all the woof of falsehood. If I were not so completely up against it, I’d chuck the whole business and go back home.”

James Wells’ face hardened slightly, and he bit his lips to suppress an emotion which the younger man’s words caused him to feel.

“Look what we’ve been doing here for the last year, nearly,” Randall continued savagely. “Arousing these slow minded Japanese to believe that the United States is sitting up nights figuring out how to rob her of her spoils from Russia. Everything that has come up we’ve turned to our ends. Those San Francisco immigrant cases we twisted about so that the Japanese believed that their people were being hung from the lamp-posts. Now we are trying to dispose of the Chinese battle-ships to the country that’s silly enough to buy them. We’ve made the Japanese believe that the American fleet is only waiting to seize them before coming north from Manila and putting Japan entirely out of business.

“The surprise to me is,” he added gravely, “that men like Captain Inaba and the Emperor’s ministers believe it.”

“When you hear a thing every day, served up to you with all kinds of fancy dressing, by and by you begin to believe there must be something to it,” Wells answered with a smile. “Your eloquence, George, is so wonderful that sometimes, ’pon my soul, I believe it myself.”

Randall smiled grimly at the implied compliment to his pen.

“It’s a low underhand game we are playing,” Randall exclaimed. “We are nice Americans to be doing such work. I’d like to see that yellow sheet, the ‘Shimbunshi,’ suppressed; then you and I would be out of a job.”

“Yes, and ten thousand a year,” Wells answered; “that’s more than we’ll ever make again; and most of mine is going to a bank at home.”

Randall heaved a sigh.

“I wish I was on to Impey’s real game,” he said thoughtfully. “He knows all the big men here. He goes up to see the Chinese ambassador and dines with him informally. He just came back from Peking the other day and let drop a remark to me in a thoughtless way that told me that he knew Lord Li, and Chang-Shi-Tung well. He learned Chinese from one of the big men there who has a seat on the Wai-Wu-Pu, the privy council to the throne of China. There’s more in it than just selling battle-ships, I’ll make a bet on that.”

Randall shook himself very much as a big dog would after coming out of the water, as he exclaimed feelingly:

“Of course there’s more in it. Impey’s stirring up a war between our country and Japan, and what attracts me is the risk we run. It’s stimulating to know that if we’re ever caught a Japanese prison and rice three times a day will be our reward. And then you see, Jim, if we can bring on this war, we’re right on the ground for war correspondents. That’s an inducement for even an old shell-back newspaper man like you.”

“The world owes each of us a living, I suppose,” Wells answered sadly. “The more risks, the better pay.”

He picked up Randall’s “copy” from his desk and glanced carelessly over it. Then a spark of interest showed in his sombre face, almost immediately supplanted by oblivious concentration. Randall gave an impatient shrug and, seeing that his friend would be absorbed for quite half an hour, he threw himself in a chair to wait patiently until the reading was over.

The minutes ticked away on the big clock opposite him, and he drummed nervously with his finger nails on the arm of his chair. His glance roamed from his companion and back to the clock.

“I told Impey I’d go to the garden fête.” His voice was in a half aside. “I don’t know how he worked it to get me an invitation.” He took it from his pocket and glanced at the big black Japanese letters with the golden chrysanthemum at the top. “I suppose it reads, ‘His Majesty the Emperor of Japan requests the extreme pleasure of Mr. George Randall’s company to a garden fête to meet Her Majesty the Empress.’ I hope the dear lady was not greatly disappointed when I didn’t appear.” His face broke into a happy smile at the ridiculousness of his thoughts. “With all the viscounts and barons, to say nothing of counts and sirs, I hope it was really a relief to Her Majesty to find I had not come.

“I wonder if I should write her and explain there was no offense, but that I became so absorbed in something I was doing, to put it plainly, to make trouble for her government, that I quite forgot the time of day. But I am sure Impey made up for my absence. That fellow is a wizard, the way he pulls the wool over people’s eyes. He’s as thick as fleas with the American ambassador—and, by Jove!” Randall stopped his spoken introspection to whistle softly, “even the ambassador’s daughter has been taken in. He has a picturesque part in this show. I believe I’d like to take his end. I am not allowed to see; I only write from notes furnished me, like a blind novelist.”

“What’s all that rot you’re talking?” Wells had finished his reading and was regarding Randall, a half smile of amusement on his earnest face. “Do you know, George, you ought to be doing something worth while. This thing,” tapping the manuscript he was reading, “is a gem. How can you do it? The ‘Shimbunshi’ will make a big hit in its morning edition, and just at the time when Japan is entertaining our officers. To-morrow the American captain is to lunch with His Majesty.”

Randall heaved a sigh and rose from his chair. “Jim, if I could get out of this thing honorably, I’d do it to-day, but I can’t go back to that little old town in Indiana without money. They’ve got me here solid. Good-bye, Jim; I am going down the street and talk to some of those clean looking American sailors I saw this morning. I am just hungry to hear them talk. You’re such an old musty bookworm that you don’t know what it is to pine for the latest slang from little old New York.”

After his companion had gone, James Wells sat silent at his desk. His mind was reviewing the last few years of his life, conjured out of the almost forgotten past by Randall’s boyish outburst.

Little by little his friend was making him see their calling through younger eyes. He was himself an old newspaper man. All news to him was merchandise to sell to the highest bidder. To highly color it, to make it more readable, was part of the game. No idea of being a traitor to his country or a spy had ever entered his even, methodical, sober thoughts until this youngster had sowed the insidious seeds. Was he really harming his country? He had never thought of it in that light. Every country was advancing in military and naval development and he had been put at the head of the Tokyo office of a newspaper syndicate whose avowed purpose was to collect all manner of news affecting the armaments and also the political relations between countries. If he thought that this syndicate had for its aim to strain the relations to the breaking point of two naturally friendly countries, one of which he still considered his own, why then he would quit, and go back to a minor position on a big New York paper which he knew would always be open for him. He had not always been shown the effusions of Randall. His work was to systematically arrange the information received so that Impey and Randall could use it. He picked up George’s manuscript and let his eyes wander slowly over the scrawl.

“It seems peculiarly paradoxical that a cruiser of the United States navy, commanded by an officer who until recently was at the head of the Bureau of Naval Intelligence, should be sent to Japan just at the time when the American battle-ship fleet having sailed for the Orient via the south of Africa, has arrived in Manila Bay. And is it less of a paradox that one of her officers is the inventor of a torpedo which is rumored to have the greatest range of any yet tried in any navy? Again another officer is known to be an experienced aeronaut, having been until recently the instructor with naval flying machines at Washington. If one will take the roster of officers and give it a close scrutiny he doubtless will discover that every method of prying into the naval preparedness of Japan for war is represented by an expert.”

Wells looked up from his reading and there was a flash of fire in his steel-gray eyes. “George is a darned hypocrite. He had the nerve to write this, and then preach to me about our dishonorable trade.

“I wonder how much of this is true. Impey doubtless furnished him with the data.” He seized the sheets, and read on while the clock ticked the seconds slowly away. Finally he finished, put the copy into an envelope, and struggled into his coat. “This must be in the ‘Shimbunshi’s’ office this afternoon if it is to make the sensation intended,” he muttered grimly to himself as he pulled his slouch hat over his thick hair. “I’ll make sure and take it myself,” he ended decidedly as he shoved the letter into his inside overcoat pocket and buttoned it tight before he issued forth into the street.

About the same time two sailormen were striding along one of the main thoroughfares of Tokyo. They both towered head and shoulders above the people about them.

“It’s been nearly five years since I first visited our little Japanese brothers. They’re a curious lot, but, Bill, there ain’t nothing soft about ’em.”

Boatswain’s Mate John O’Neil glanced as he spoke at his companion, Seaman Bill Marley, both from the “Alaska.”

“In that war with the Ruskis they were right up to snuff,” he continued, as they strolled along aimlessly. “They saw their work and they went for it, and stayed on the job until it was finished.”

The two man-of-war’s men had come to Tokyo on the special train for a forty-eight hours’ liberty in that Eastern capital, and were enjoying themselves thoroughly. Everywhere they met welcoming smiles, and even the little urchins playing in the streets stopped, and raising their tiny hands aloft, cried “Banzai” as they passed.

The day was balmy; the air laden with perfume of many flowers. In the shops they had seen many beautiful things and had spent a portion of their slender pocket money on such articles as took their fancy, marveling the while upon the smallness of the price.

“Say, Jack, look here; all this war talk is soap-suds, ain’t it?” Bill Marley asked.

O’Neil contemplated the back of a man a half a block or so farther up the street before replying.

“He’s in a big hurry about something,” he muttered half aloud, and Bill Marley asked, “What’s that?” for he had heard O’Neil speak, and thought it might be an answer to his question.

“Oh, about this war talk,” O’Neil responded, his mind reverting from the stranger ahead, whom he made out to be a European in a big hurry to get somewhere. “I don’t take no stock in it. There ain’t nothing that I can see we’ve got to fight for, unless it’s just to see who’s the best man. This war business cost too many people too much money. These Japs are nice little fellows; they like us and they want to show us they like us. They are mighty proud of their knowledge of fighting, too, and they’ve got a code of honor they call ‘Bushido,’[1] or something like it, which means, as far as I can find out, ‘If any one insults you, and you can’t lick him, cut yourself open with a sharp knife.’ Now fellows with ideas like that ain’t to be monkeyed with. If we treat ’em square and be careful about treading on this ‘Bushy porcupine,’ they’ll continue to yell ‘banzai’ at us, but if we get funny and put it over them in some way, they’re apt to tackle even us.”

“And if we lick them,” Bill Marley asked, “then I suppose they’ll take to the tall timbers and disembowel themselves?”

“That’s about the situation,” O’Neil replied, “but as far as I can see there ain’t no sense in fighting. Can’t we leave these little fellows alone with their troubles? Ain’t we got enough to do in those South American republics, with them at each other’s throats every month?”

“Yes,” Bill Marley acknowledged thoughtfully. “Why does any one want to spoil a nice place like Japan by going to war? I’d rather make a liberty here than any place I know—outside of the Bowery.”

O’Neil paid this answer but scant attention. He had seen the European ahead fairly run down the street and become lost within the crowd. Upon approaching nearer, a piece of white paper caught the sailor’s eye as it lay on the tiny sidewalk, almost on the edge of the crowd. Had it been dropped by the European in his haste? The sailors picked it up, and Marley shoved it down the bosom of his shirt for safe-keeping. It was a long white envelope addressed to the “Editor of the ‘Shimbunshi.’” O’Neil had read the inscription as Marley held it toward him.

“That’s for a yellow journal published in Tokyo. Hold on to it, Bill,” he instructed. “There’s a row on here,” he added excitedly as they pushed their way forward.

The two men soon realized that this crowd was more than a simple assemblage on a street corner. From a swaying motion inside it appeared that a struggle was in progress at its centre. They now again saw the stranger pushing his way through, his head towering above the shorter Japanese around him.

“I hope it ain’t a rikisha fight,” Bill said eagerly, as he hurried after his companion. “These rikisha coolies is mighty mean when you don’t give ’em three times the fare.”

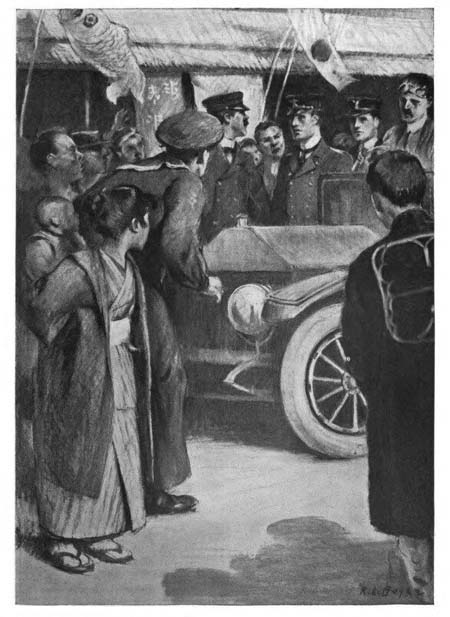

“Come on, Bill, quick,” O’Neil exclaimed, but there was scant need for urging. Both had seen enough to know that what was happening was a great deal more serious than a rikisha fight. The midshipmen were in danger from a mob.

“Put your shoulder in the small of my back and shove,” O’Neil cried excitedly, as he dived into the crowd thickest about the machine, scattering the people left and right. They were at the wheel of the motor car before the mob could take in the meaning of this human battering-ram.

“What’s the row, sir?” O’Neil asked hurriedly, turning toward the crowd and pulling up his sleeves in a businesslike way.

“We ran over a man,” Phil replied in a nervous voice. “I hope he isn’t dead. They took him from under the wheels and carried him over there,” indicating a small house about the door of which many curious people had collected. “Can’t we persuade the crowd to let him go on?” he added anxiously. “They would have killed him a moment ago.”

“WHAT’S THE ROW, SIR?”

O’Neil raised his voice and shouted “Junsa” at the top of his lungs several times. Immediately the crowd moved backward. Three or four policemen (Junsa) appeared suddenly as if they had leaped from within the earth and cleared the way in front of the machine.

“Tell them we’ll answer for his appearance before the authorities,” Phil said to O’Neil, in his excitement, believing that O’Neil could interpret for him. However, he was not far wrong, for the sailor’s sign language was quite clear enough.

“Blow your horn and beat it, mister,” O’Neil sharply directed the driver of the car. “It’s getting to be a habit with you, I see,” he added maliciously to Impey. “The man in such a hurry too,” he murmured as he recognized the man on the front seat next the driver.

Impey made a hasty recovery, and with his horn blowing, the car glided cautiously away, leaving the Americans to grapple with the situation.

“It would have served him right if they had given him a sound beating,” Sydney cried indignantly a few moments later as they looked down upon the white face of the victim lying on a mat within a tiny store opposite the scene of the accident. “Has a doctor come?” he asked solicitously; but the Japanese addressed only shook his head, saying something in his own language which Sydney interpreted correctly to mean that he did not understand.

“Why doesn’t some one get a doctor?” he exclaimed. The strain of helplessly watching the sufferer was becoming unbearable. “Are you a doctor?” he asked as a uniformed naval officer forced his way through the curious throng and knelt at the injured man’s side.

With fascinated eyes the lads watched this grave little Japanese examine the injured man. They saw his nervous hands move quickly over the senseless form, resting momentarily here and there to make sure before passing on to other parts of the crushed victim’s body. Finally he rose to his feet while ready hands tenderly lifted the silent figure to carry him away.

“He will not die; luckily the wheels did not pass over him. Only contusion of the head and a broken leg,” the little doctor said in studied English and with a very impressive professional smile, as he shook hands with the midshipmen. “I was in the navy department building, and came as soon as I was informed. He is an employee in one of the offices, and was out with a message.”

The midshipmen followed the doctor into the hallway of the navy building, where the injured man had been taken. They were quickly surrounded by naval officers, asking for the story of the accident. Phil found himself talking to Lieutenant Takishima, while behind him stood Captain Inaba listening eagerly. There seemed to be much concern over the deplorable affair. Several officers went out hurriedly and soon returned, their faces grave, to make their report to Captain Inaba. What was the meaning of so much concern over the mishap to a mere employee?

“Can I not give him something, poor man?” Phil inquired anxiously, producing his purse. “Of course, Mr. Impey will provide for him, but maybe a little money would aid his family.” He innocently attempted to put the bank-note into the victim’s pocket, but much to his surprise his arm was held tightly by Captain Inaba. A look into the naval man’s face convinced him that the attitude of those about them was not friendly. Did they then blame Sydney and him for the accident? Surely they could not be so unfair.

The midshipmen quietly withdrew, seeing that their presence was a source of embarrassment. They found O’Neil and Marley waiting for them, having engaged and held four rikishas. All thoughts of the ambassador’s reception had quite passed out of the lads’ minds, so they were soon on their way to their hotel as quickly as their coolies could carry them, the sailors bringing up the rear.

“What is it, Marley?” Sydney asked as Marley signed them to stop as they alighted and were entering the hotel.

“We’ve got something important to show you,” O’Neil said mysteriously, his face grave, while Marley nodded soberly.

“Come along then,” Phil answered, leading the way through a side entrance which opened on the court near the rooms assigned the American naval officers.

O’Neil closed the door quietly, while Marley nervously put his hand within his sailor blouse and produced the big envelope which he had hidden within.

Phil took the proffered letter in silence.

“The ‘Shimbunshi,’” he read aloud. “Why, that’s for a Japanese newspaper published in Tokyo. Where did you get it?” he asked.

Marley had turned red and was stammering incoherently. O’Neil came to his rescue.

“It was lying in the street just before we hit the crowd, sir, and Marley picked it up. I advised him to keep it snug.”

“But we must send it to its address; we have no right to keep it.” Phil’s voice was indignant.

“Just as you say, sir,” O’Neil answered without emotion. “You notice, sir, it is unsealed.”

Phil was devoured with curiosity to read the contents. The scene in the hallway of the navy building now took on a new aspect. The injured man was Inaba’s messenger. So ran Phil’s thoughts. He had been entrusted with this letter. He had lost it. That surely was the cause of the perturbation of the Japanese naval men. Some naval secret, perhaps, but undoubtedly in Japanese, which they could not read. The more honorable thing to do would be to go back post-haste and deliver the letter to the Japanese navy department.

“It’s in English, sir, and it’s about us.” Marley had found his tongue during the silence. “I stole a look while you were in the building.”

Phil’s curiosity had beaten down all scruples of honesty, and his eyes were running rapidly over the words of the letter. At first only amusement showed in his face, but it soon gave place to surprised indignation and anger.