CHAPTER VII

THE SECRET DOCUMENT

PHIL reached the ballroom just as the music had stopped, and looked quickly about for Sydney. He saw him at the far corner of the room and hurried to his side.

“Syd, get your coat and hat and meet me at the door, quick!” he whispered excitedly. “I’ll stay to explain if necessary,” he added, glancing at Helen, the centre of a group of officers.

Sydney would have asked for an explanation, but a look at his friend’s face showed him that it was a matter of grave concern. Helen became suddenly conscious of something unusual. She had caught the danger signals in the excited faces of the midshipmen as she glanced their way just as Sydney was on the point of leaving.

Phil knew that some explanation would be necessary. “Go on, Syd,” he urged; “I’ll tell Miss Tillotson and then join you.”

Sydney had gone, picking his way across the crowded room. Helen was standing beside Phil, her eyes dilating with apprehension. “What is it?” she exclaimed in a low voice. “Has anything happened?”

Phil cast about for appropriate words to explain something which he himself could only guess.

“Where can I leave you?” he began tentatively; “for I must hurry if we are to be of any service.” The officers who a moment before were with her had gone.

“Can’t I go with you?” Her face was flushed and her eyes bright with excitement at the thought.

“I don’t even know where we are going,” he replied, his voice deprecating the idea of her accompanying them. “It might be something serious. I couldn’t think of putting you in any danger.”

Phil was relieved to see Lieutenant Winston making his way toward them. He waited impatiently until Winston reached Helen’s side and then hurried away without a word of further explanation.

Outside the brightly lighted entrance Takishima was waiting; three rikishas stood ready, and the three classmates lost no time in jumping in. Takishima quietly gave the directions, and the next moment they were rolling rapidly along the evenly paved boulevard. Takishima’s rikisha was in the lead, while Sydney and Phil trailed after in single file. The Japanese policeman ran along at Takishima’s side.

Phil was in an agony of suspense. He longed to ask what the trouble was, but to do so he would have had to shout at the top of his voice. He thought over all the things that might have happened, becoming more anxious as the minutes dragged by. He saw that his coolie was lagging behind, while Sydney’s kept close up to Takishima.

Phil called loudly the word he had heard meant hurry, “haiaku,” but the distance between Sydney and himself slowly increased.

Phil’s coolie was evidently giving out; he could not keep up the pace set by Takishima. Phil was on the point of getting down and running to catch up. He was sure he could easily overtake them.

Suddenly Phil’s rikisha stopped, and the coolie lowered his shafts to the ground, breathing heavily and wiping his face with a large handkerchief. The lad glared at the Japanese angrily and roundly berated him for his incompetence, but he soon realized that he was but wasting precious moments; his companions were now far ahead. He gazed about him anxiously. The narrow street was dark and deserted, the road ahead was empty. Takishima and Sydney had turned to the right or left, but in which direction Phil had not seen. Planting his cap firmly on his head the midshipman ran swiftly down the street.

A cry for help came feebly to his ears. The lad stopped abruptly, his heart beating wildly, for the cry was in English. He saw he was in the old business section of Tokyo; the houses were mostly two-storied. Again a cry came to him faintly, as if a man were being throttled in the house beside him. Phil sought in vain for an entrance, shouting a word of encouragement. What could it be? Was an American sailor being robbed? There was no room for further doubt; a high piercing cry of a man in mortal fear filled the air, and suddenly died abruptly away. There was evidently not a moment to lose, but where was the entrance? A dark alley caught his eye a few feet ahead, and down this narrow lane Phil turned quickly. A door on the right stood open; a flight of steep steps led to the second floor. Floundering noisily in the dark he rushed on. Reaching the landing, he perceived a light shining through a chink in the farther wall. With pulse throbbing loudly in his ears he stopped guardedly to listen. A scratching noise of a struggle came indistinctly to him.

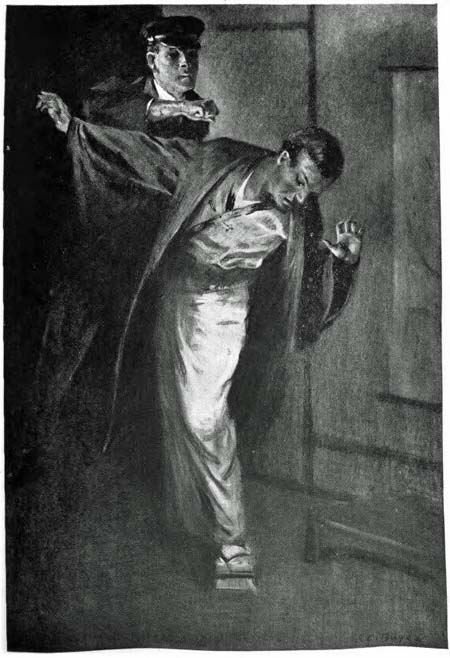

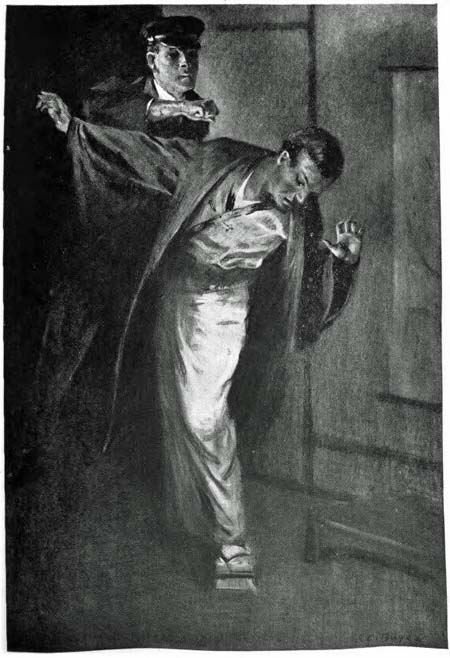

What should he do? How many ruffians must he face? The lad suddenly remembered that he carried no arms, while the robbers inside must be well provided. While he yet hesitated a door suddenly opened, and the hallway was flooded with light. On the floor of a large room two men were struggling, while on the threshold stood a Japanese quietly watching the unequal battle. His back was turned to Phil. Spellbound, stupefied, the youngster stood scarcely out of arm’s reach of this trim, stocky figure, garbed in the usual costume of a man of the middle class. Phil saw that he must act. To retreat would only cause his discovery and then the little Japanese would be forced to attack. Phil held himself rigid.

Silently he edged nearer the unconscious observer of the struggle; the man on the floor was now lying almost motionless, while the figure above him clung closely to him. Phil had reached the very edge of the door, and his victim was yet unconscious of his presence. For the fraction of a second the lad hesitated. A thought as terrifying as unbidden had come into his mind. Were these men detectives? If so he would be assaulting the Japanese police. Then all precaution was swept aside, for he remembered the cry for help was in English. He could not tell whether the victim on the floor was a sailor or not, but his spirit of chivalry spurred him on to take the part of the weaker.

THE JAPANESE GENTLEMAN

WENT DOWN

A loose board under Phil’s feet suddenly creaked with a ghastly sound, causing the man at the door to start and turn his face toward the hall. In that fleeting second Phil read authority and character in the quiet aristocratic face, and the next moment the Japanese gentleman went down under a sledge-hammer blow from Phil’s fist. The midshipman had mapped out his battle plan. He saw the man who had nearly squeezed out the life of the victim on the floor was powerful, and in a hand-to-hand fight Phil with all his muscular development might be worsted. The lad could take no chances. The first blow had been delivered so quietly that the second man had not divined what was going on behind him until a blow on the head from a heavy chair in the midshipman’s hands caused him to relax his muscular fingers from the blackened throat of Robert Impey.

Phil gazed terrified about him. Three men lay motionless on the floor, while two of them had been stricken by his own hands. The first to fall lay deathly pale on the floor. Phil leaned over and listened for his heart beat. He had delivered a blow which he knew could hardly kill, but in the stillness of the room he would not trust his own judgment. At the man’s side, as if it had fallen from his hand, lay a large white envelope. Phil grasped it eagerly. The seal was broken, and inside lay a dozen official sheets of Japanese writing. On the outside were great black characters and the gold seal of the Emperor, now torn and mutilated.

Phil’s heart rose in his throat as he suddenly realized the meaning of the attack on Impey. These men whom he had just rendered senseless were employees of the navy department—secret service men. They had tracked Impey, believing he had the stolen document. The lad, in a fever of dread, crossed to the table and extinguished the light, and then he crept away down the creeking dark stairs, his brain in a tumult. Reaching the street, he gazed fearfully about him. The place was deserted. He walked a block and then broke into a run, fleeing from the horror behind him. Not knowing which way to turn, he kept straight on until he saw several rikishas coming toward him, when he abruptly turned to his right and ran faster.

“Phil! Hold up! Wait!” came joyfully to him as he slackened speed and allowed his companions to overtake him.

“We’ve wasted nearly a quarter of an hour looking for you!” Sydney exclaimed as Phil trotted breathlessly at his side. “What have you been doing?”

Phil evaded the question, breathing heavily as an excuse for not talking. A terrible guilt was on his mind. The secret and important letter lost by the messenger Oka, containing that which if known by America might strain the relations between the two countries, lay next his rapidly beating heart.

“Where is it? What is it?”

“Taki says it’s a riot,” Sydney returned. “There you are!” he exclaimed, pointing. They had emerged into the lighted thoroughfare, and Phil’s question was answered. Scarcely four blocks down the street a great crowd could now be seen completely filling the street.

Phil’s pulses beat faster. A riot—and American sailors the cause! At this time it might lead to grave consequences.

Takishima had stopped precipitously; it was too dark to see his face, but his voice expressed quite distinctly the anxiety he felt.

“How has this happened? Some one shall suffer for this blunder!” he exclaimed angrily.

The mob was pressing toward the brightly lighted entrance to the theatre, but the doors were closed, barring its entrance. Though there were many policemen present, they seemed unable to control the ever-increasing crowd, whose angry voice could be heard, raised ever louder and louder.

“This is a case for soldiers!” Takishima had cried out in English, and in his excitement talking to the little guide, who stood mute and mystified.

Across the street Takishima darted, telling the midshipmen to wait where they were.

“With all their training for discipline, the Japs are just like any one else.” Sydney’s voice betrayed his excitement, but he felt he must say something to relieve the tension. “Winston should be here to see this. No riots in Japan!”

Phil gulped hard. “What’s happening inside?” he gasped. All thoughts of the two men he had rendered unconscious were forgotten.

“There are two hundred of our men in Tokyo; if they hear of this they will come on a run from all over the city.” Sydney’s diagnosis was not reassuring.

“A fight between our men and a mob would mean indemnity, for some of them would be sure to be killed and wounded,” Phil said tensely. “Do you recall the Chile trouble, when we nearly came to war over just this same kind of thing?” Phil’s thoughts were pessimistic. Both lads were aware of the terrible possibilities. They thoroughly understood the workings of their sailors’ minds. Once they heard their companions were in trouble the American sailormen would flock to the rescue. “My countrymen—right or wrong,” is ever their motto.

The impatient midshipmen could stand the strain of inaction no longer.

“Where is Taki? Why doesn’t he return? Where did he go?”

Forgetting in their excitement the inability of their guide to speak English, they were pulling him violently by the arm toward the rioters, but the little policeman had received his orders, and remained firmly planted where Takishima had left him.

The naval officer suddenly reappeared.

“I have telephoned,” was his reassuring greeting. “There’s a back entrance to the theatre.”

The four were retracing their steps. An alley, dimly lighted and deserted, opened before them and, led by Takishima, they rushed down and through its many turnings. A heavy door barred their further progress. With hearts beating tumultuously they listened to the babel of angry voices from within.

The door was locked. The combined effort of the four failed to discover a weakness in the solid wood.

The midshipmen gazed wildly about for a means of breaking the lock.

Takishima soon solved the difficulty. The policeman, agile as a cat, was scaling the side of the house. Above him was a window through which a light was shining. Breathlessly and impatiently they waited while he climbed slowly upward. Then he disappeared through the window and after a few anxious moments the door was opened and they rushed within, securely locking the door after them. Up the stairs they ran, and then suddenly the full magnitude of the situation burst upon them.

A score or more of American sailors had captured the theatre stage and, with clubs and sticks stripped from the scenery, were holding at bay several hundred infuriated Japanese.

Phil recognized O’Neil and Marley in the foremost ranks of the defenders, and his heart sank, for he realized that O’Neil would not abet a fight without real provocation.

“You go to your men. I’ll hold the crowd in check until the soldiers come,” Takishima exclaimed, as he threw off his cape and stood in full evening uniform, his golden epaulettes glistening brightly and his war medals sparkling on his breast. He walked out fearlessly between the sailors and the clamoring crowd. Phil and Sydney had placed themselves between him and their own men to protect him from a chance blow.

“Back, men, all of you. Do you realize what you are doing?” Sydney’s and Phil’s voices were tense with anger and excitement as they pressed the sailors away from their foes. “You, O’Neil, leading this disgraceful row!” Phil cried out accusingly and in tones that at the same time expressed the lad’s bitter disappointment upon seeing the boatswain’s mate involved in what appeared to him to be a disorderly fight against well-intentioned Japanese citizens.

“It wasn’t O’Neil, sir, what started it.” Bill Marley’s voice was raised excitedly. “This is what they was dragging on the stage, sir, wiping their clogs on, and the man what carried it wasn’t no Jap. I can take my oath on that. He ‘beat it’ when he seen there was a row on.”

The midshipmen opened their eyes in amazement as Marley showed the tattered American flag in the defense of which the American sailors from all over the theatre had collected.

“Never mind that now!” Phil waved for silence as several excited voices were raised expressing forcibly the desire to be allowed to clean out the place and revenge the insult to their flag.

“Can’t you see by Marley’s evidence that it was fixed up on you?” Phil exclaimed, grasping at a straw. “The man with the flag was not a Japanese. Who was he? A sneaking, cowardly foreigner, anxious to bring about a conflict between you American sailors and the citizens of Japan.” Phil was eloquent in his anger and mortification. “And you, led into the trap like lambs. Aren’t you ashamed of yourselves?”

“What could we’ve done, sir?” An oppressive silence had descended upon the sailors; but a single one mustered up courage to half defend his companions’ actions. “We couldn’t just sit tight and watch; now could we, sir?” This last was said appealingly.

“No. I suppose it was natural,” Phil admitted grudgingly, “but now you know that you’ve been ‘buncoed,’ just turn about there and we will try to smuggle you out without another disturbance.”

Takishima was at a loss to understand the cause of the trouble. His great fear was that it had come about through the general ill feeling being spread broadcast in Japan by the Japanese newspaper, the “Shimbunshi.” As Marley called the midshipmen’s attention to the flag, the lieutenant turned about hastily, his face showing perplexity.

“An American flag,” he exclaimed in English. “I can’t understand. This is a scene from our last war. Could it have been a plot? You say the man who carried it was a foreigner. Yes, it was a plot, devised to bring on a fight between you and our people.”

Meanwhile Impey, as he lay unconscious on the floor of his office with the two men who had endeavored to take from him the stolen document, themselves senseless near him, might, if he had known, felt proud of the plot which had all but succeeded in precipitating a riot. While the events at the theatre were taking place the two defeated secret service men slowly came to consciousness. Impey lay inert, half dead on the floor. They rose defeated, mystified, for neither had seen his assailant. The precious document had gone. They quietly slunk off down the stairs to lay before their chief, Captain Inaba, the sad story of their failure after having the lost paper within their grasp.

The American sailors on the stage were lost in admiration at the dignified manner in which Lieutenant Takishima stemmed the tide of anger. At first beyond control, threatening to attack the score of sailormen who had outraged the spirits of those who had fallen in their last war, the crowd grew quieter until the people suddenly became silent, intently listening to the lieutenant’s calmly spoken words. What he was saying the Americans did not know, but they saw that he held their attention upon an order worn upon the breast of his full dress uniform. It was the order of the rising sun; the sacred emblem of their Emperor was the mystic talisman that cast an hypnotic spell over that vast assemblage and forced them to listen to reason.

“That’s the most marvelous thing I’ve ever seen.” Sydney’s excited whisper brought forth what was almost a cheer from the astounded Americans.

The Japanese audience gave way; moving as one man back toward their seats, their upturned faces were again good-natured.

Loud cheers of “banzai” echoed through the theatre, while several strong voices were raised at different points of the house, followed by cries of agreement from the multitude.

Takishima had turned toward the Americans, and was speaking to them in English.

“My people are sorry that this has occurred, and desire to say that they honor the Americans for their patriotism. They did not understand the reason for the interruption, but now that they see, they wish to beg the pardon of the sailors.” Phil as spokesman answered by proposing three cheers for the Japanese nation, which were given with a will, and the irrepressible Marley waved his flag, which had been the innocent cause of the trouble, high in the air.

The audience filed out of the theatre in orderly fashion, and as the wide doors were thrown open the midshipmen saw drawn up across the street a company of regular soldiers, those who had been summoned by Takishima.

“I would advise getting your men out by the back entrance.” Takishima was smiling, but his face was pale and his dark eyes bright with suppressed excitement. The lads noticed that the hand which raised his cloak trembled violently. Then they realized for the first time that the ordeal through which this youngster, scarcely a year older than themselves, had passed, had been one requiring every ounce of his nerve and grit. One mistake and the tide might have been turned against him, and the sacred order on his breast, the “rising sun of the second class,” would have been defiled and himself dishonored in the eyes of his brother officers.

“Although Taki speaks our language the working of his mind is as different from ours as is the East from the West,” said Sydney. “What have we in our country symbolic of majesty or power?” he asked in a low voice. “If you or I had attempted to quell a disturbance in a New York theatre what could we use to bring the scattered ideas of the vast assemblage together?”

Phil silently pointed to the flag as yet firmly clutched in Marley’s hand. Sydney nodded, half convinced only that his countrymen’s patriotism could be aroused by it to the point of obedience to a stripling’s orders.

A blush of shame crept into Phil’s face as he suddenly remembered the secret document in his pocket. Would it not be a courteous act to give it over at once to Takishima to restore it to those who were anxiously searching through the entire city and who would be forever disgraced if it fell into the hands of the agents of a foreign power?