CHAPTER IX

MORE DISCOVERIES

O’NEIL and Marley decided that they had best leave Tokyo for the present. Their uniforms, which had been neat and trim when they arrived, were now in the bright light of morning in a deplorable state, torn and stained with dirt from their struggle in the theatre the night before.

“We are certainly hard-looking citizens, Bill,” O’Neil remarked sadly as they rapidly clothed themselves in their tattered remnants, “and a whole day more leave to our credit, too.”

Both sailors knew their first duty was to give to the midshipmen the information which they had been directed to get from the injured messenger, and this duty was now all the more urgent, for O’Neil carried within his torn uniform blouse the much sought document itself.

He had picked it up on the stage of the theatre. At the hotel they were told that the midshipmen had gone, and believing they had returned to the “Alaska,” they were just in time to catch a fast train for Yokohama.

“Bill, how would you like to fight these little Japs, eh? It wasn’t such hard work last night, was it?” O’Neil asked.

“No,” Bill answered conditionally. “They had a look in their eyes, though, that wasn’t no way pleasant. It seemed to tell you: ‘Go ahead and down me; there’s lots more anxious to take my place.’”

“Right you are, Bill,” O’Neil smiled grimly. “They’re fatalists; it ain’t nothing for them to die, no more than for you to get a tooth pulled. When a man is killed in battle here his family have a big celebration and invite all their friends in to help them.”

“Have they got as good ships as ours?” Marley questioned.

“Ain’t you ever been on board a Jap battle-ship?” O’Neil asked in surprise. Marley shook his head. “Well, the next time we go ashore we’ll go down to the dockyard at Yokoska. They are mighty perticular, but I reckon we can get tickets through that Jap officer friend of Mr. Perry’s. But mind, Bill, you don’t let your fishy eyes rest too long on anything you see, and leave your kodak on board ship.”

Marley’s face wore a disgusted and pained expression. “You know, Jack, that I ain’t none of these long-haired, mushroom sailors with a ‘snap me quick’ over his shoulder.”

O’Neil laughed loudly. The idea was amusing. Then he caught sight of a familiar figure, just passing their compartment.

“Hello, you old parchment-faced pirate,” he called, and Sago, the Japanese steward, entered bowing and smiling.

“What did you mean by taking us into that hornet’s nest last night?” the sailor continued banteringly. “You might have known my friend Bill here would have ‘started something’; he usually does.”

Marley let the remark go. He was ever a lap or two behind Jack O’Neil in his train of thought.

“Bill, could you recognize again the fellow who carried the flag?” O’Neil suddenly asked. “If we could lay our hands on that gentleman we might find out something useful. Did you hear Mr. Perry tell us that he and the little Jap lieutenant believe it was a fixed up game to start a row with our men?”

“It’s all too mixed for me. I can unmoor ship from an elbow or a cross, but when my cables are all tangled up in knots, then I am done.”

Marley had lapsed into a sailor metaphor indicating that the devious ways of diplomatic intrigue were beyond his simple comprehension.

“Sago, what does your methodical brain tell you is the real game being played here in Japan?” O’Neil directed his eloquence upon the silently complacent steward. “Do these one time countrymen of yours want to annex the United States?”

“No.” Sago was emphatic in his negative. “Japanee very funny, all time want to learn something. American they don’t understand. They think Japanee very curious.”

“Say, Sago,” O’Neil turned on him suddenly, and the little old man started in mild surprise, “suppose we had a war with Japan. What would you do? Skip back here and go in the Jap navy?”

Sago was indignant. “I wouldn’t ever fight against the United States,” he declared positively. “Sago think Japan no want to fight. Plenty soldiers and sailors, but no money.”

“Strike me blind, if there ain’t that yellow villain what carried the flag.” Marley was half out of his seat, his eyes staring at what appeared to be a Japanese servant by his dark blue livery. In his hands were several valises, and in front of him, just entering a compartment in the same car as our friends, were two Europeans.

“Our friend Randall,” O’Neil exclaimed as he laid a detaining arm about Marley’s waist. “Hold fast, Bill, there may be something in this. Just sit tight and wait. They ain’t going to get away until we reach Yokohama, because this is an express.”

“You got that paper there, Jack?” Marley asked as he saw O’Neil’s hand down inside his blouse.

“She’s safe anchored here,” O’Neil replied, “and I can’t keep my hands off it. I’ll bet a month’s pay it’s the same one that little Jap messenger lost.”

The two sailors had examined it the night before in their room by the faint light of a Japanese dip and the markings were the same as that described by Oka.

O’Neil drew a letter stealthily from his pocket, while Marley put his back against the door to ward off interruptions.

“Give us the dope of this in United States, Sago,” O’Neil ordered as he held out the official document to the awe-struck steward. Sago’s eyes were as big as saucers.

“Where you get him?” the Japanese asked, making a quick grab for the letter and in his excitement forgetting to speak good English.

“Belay there!” O’Neil cried angrily. “I’ll hold it right here and you can read it backward[2] to us.”

“This very serious,” Sago exclaimed fearfully. “If some one see us we all go to Japanese jail. That Emperor’s letter. More better you take quick back to Tokyo.”

“Not on your life. I am going to know what these officers were so anxious about,” O’Neil declared while Marley wagged his head in confirmation of his chum’s sentiment. “If you’re as good an American as you try to make us believe you are, you’d read it instead of trembling there like a Chinaman about to get his head chopped off.”

Sago read the letter slowly to himself. After his first surprise his natural sagacity asserted itself. He knew that the real contents of this letter should not be told the sailors. He trembled at the thought of knowing it himself. He must satisfy these two determined men and then endeavor to get the letter into his captain’s hands. Sago saw that a military secret had been taken from a nation which prided itself upon its power to keep such secrets.

“That say nothing.” Sago had expelled the anxiety from his voice.

“Read it,” O’Neil demanded.

“It says that next month Japanese navy will have very big drills and that all ships will be present to be reviewed by the Emperor.”

Sago looked up, his face now quite composed. “There is plenty more, but all orders of the admiral what each ship is to do.” Sago had made this up quickly and O’Neil and Marley saw no reason to doubt the honesty of his translation.

“If I’d known that was all there was to it, I wouldn’t have taken the trouble of throttling that little Jap for it last night,” O’Neil exclaimed in disgust. “I’d let him have it, for I suppose that’s what he was after when he was hunting through my clothes.”

“Where?” Sago asked quickly.

“In that joint of a hotel where Bill and I put up. They searched our room while we was asleep, but this was next to me under my shirt.”

Sago looked worried.

“Where you get him?” he asked excitedly, touching the letter with his hand.

“I found it on the stage of that theatre after the row last night,” said O’Neil placidly. “I was goin’ to hand it to Mr. Perry, but he got away before I could slip it to him on the quiet.”

O’Neil had made up his mind to know more of the movements of Randall, and with this intention in mind he placed himself deliberately in his path on the station platform when the train had arrived at Yokohama, a good-natured smile on his Irish face.

Randall appeared nervously apprehensive as he gazed about him, while his older companion and the half-breed servant hurried ahead in the direction of the entrance to the station.

“Going away?” O’Neil asked shortly, falling into step at Randall’s side.

“Taking a little trip for my health,” was the answer.

“Where you going?” O’Neil insisted.

Randall turned upon him, an angry frown on his face.

“I don’t see, stranger, as that’s any of your concern,” he replied shortly.

“Just a little friendly question, Mr. Randall,” O’Neil said evenly. “May I inquire if Mr. Impey is going with you?”

Randall’s face turned suddenly pale, and the hand holding the morning paper shook perceptibly.

“You know entirely too much,” he cried unguardedly.

“Oh, ho!” O’Neil exclaimed, “and the yellow boy there off the stage. I see he’s in the party too, eh?”

Randall had stepped between the shafts of a rikisha into which he was about to enter, with one foot on the step.

After all, what had he to fear from this American sailor? The jig was up, and perhaps he could be made useful. Why then make an enemy of him?

“I am going to the English Hatoba,”[3] he replied quickly; “meet us there and I’ll answer your questions.”

When O’Neil and Marley arrived at the landing Randall and his friends were already in a little naphtha launch.

“Get in,” Randall invited.

The sailors waved good-bye to Sago, who was waiting for the “Alaska’s” steamer, and were soon alongside a trim little sea-going yacht anchored just inside the breakwater.

“That isn’t my flag,” Randall exclaimed in a relieved voice as he stepped over the side, and pointing to the British ensign at the yacht’s gaff, “but it gives me a nice comfortable feeling of security. I have been jumping at my shadow for the last six months.”

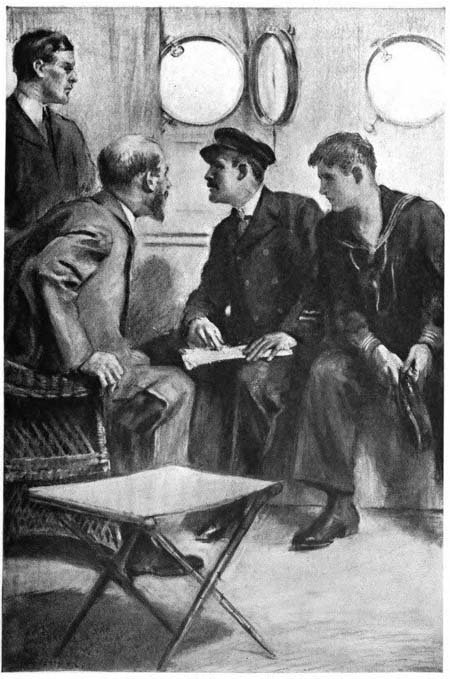

Randall led the way into the forward cabin. After the two Americans were seated he surveyed them for several minutes in silence.

“What do you know about me and Mr. Impey?” he asked finally.

“Bill and I saw you go away with him in his motor yesterday after you left us at Billy Williams’,” the sailor answered, “after telling us that you didn’t know him.”

“I don’t tell all I know to every chance acquaintance,” Randall returned; “but now as it’s all over with us I don’t mind answering your question. Mr. Impey owns this yacht, and is taking Mr. Wells and me for a little trip for our health.” Randall wore a good-natured grin upon his face as he continued.

“Mr. Impey found a very important letter yesterday, or at least Wells found it and gave it to him, and then he got robbed and was left senseless in his house last night after he had broken the seal and read it. That’s why we are changing our climate. Japan is getting a little too hot for our comfort.”

“What kind of looking letter was it?” O’Neil asked seriously, his hand in his blouse where the Japanese document was concealed. “Was it in English?” he asked.

“No, in Japanese, of course, and sealed with the big red seal of the Mikado,” Randall replied.

“Who read it?” O’Neil asked. “I thought you said it was in Japanese.”

“So I did. Mr. Impey read it. He knows their fly tracks by heart; he’s a wizard on Oriental languages,” Randall answered quickly.

“What did your letter say?” O’Neil asked earnestly. His fingers had closed upon the one hidden in his blouse.

“I don’t know all, but something about seizing or buying the Chinese battle-ships; also a lot of talk about what the United States was doing—most of it untrue and furnished by Impey and company, that’s us, you know,” including himself and Wells in a sweep of his hand. Then Randall’s eye fell upon the letter which O’Neil had drawn forth.

“Hurrah!” Randall had jumped to his feet and was hugging the astonished sailor. “That’s the very letter. Impey thought the Japs had taken it, and we were all ‘beating it’ in the yacht.”

“Well,” O’Neil’s voice was sarcastic, “some one’s been stringing you. This letter talks about a naval review of the fleet by the Emperor and a lot of other unimportant stuff.”

It was Randall’s turn to be sarcastic.

“I suppose you’ve translated it offhand yourself?” he asked, “or maybe your friend there has an intimate knowledge of Japanese classics. He looks like a scholar.”

“None of your high-brow jaw!” O’Neil’s eyes flashed; he could chaff his friend if he liked, but he resented it from a stranger. “It was read to us by a Jap steward from the ‘Alaska.’”

“Well, he did it intentionally. He was probably afraid to tell you what was really in it. But where and how did you get it?” Randall asked. Then he turned and cried aloud up the hatch to Wells who had gone to meet a boat that had come alongside, “Say, Jim, here’s the lost letter, snug enough, in this sailor’s hand!”

O’Neil explained how he had obtained it. Randall shook his head in sign of mystery.

“THIS LETTER TALKS

ABOUT A NAVAL REVIEW”

“It beats me,” he said, “how it got to the theatre. I witnessed the theatre row and afterward found Mr. Impey knocked out on the floor of his room; both happened about the same time.

“Jim lost a paper in the crowd when the man was run over,” he continued, “and one of your officers picked this up near the wheels of the motor, and Wells took it thinking it was the one he had lost.”

“So you fellows are the authors of that pack of lies about our ship? Bill there got your yellow journal dope for the Jap newspaper.” O’Neil’s face was black with anger; he saw it all now. These were the men who had aroused the Japanese nation, who had embittered them against everything American. “And you call yourself an American, too!” O’Neil’s fists were clenched tightly. “I’ve a good mind to give you a good thrashing here and now,” he cried, advancing menacingly upon the surprised journalist.

Randall was between the two threatening sailors and the hatchway, with the heavy mahogany table between. He put up his hands as if he would appease the two angry sailors, and then with the agility of a cat cleared the ladder in one bound, and the surprised sailors heard the iron hatch above them close shut with a loud report. They rushed madly up the ladder and with their combined strength attempted to force the steel door, but it withstood their combined attack.

“Shanghai’d, by Jove!” O’Neil’s voice was tearful with anger.

A tramping of feet overhead and the sound of hurried orders given in a loud voice, then a clanking of chain, came to their ears.

“We’re off, Bill,” O’Neil said sadly, “and just when things was about to get interesting. We’re playing in hard luck, sure.”