CHAPTER XVII

INDECISION

AFTER seeing Helen Tillotson to the embassy, Phil and Sydney went direct to the hotel, for there was but scant time to dress and accompany Captain Rodgers to the state dinner, given that evening by the American ambassador to the visiting officers and their Japanese naval hosts.

Bursting with the important and exciting news, the two lads, heedless of Phil’s appearance in his blood-stained uniform, went straightway to Captain Rodgers’ room. There they found their commanding officer in the midst of his toilet, and they gave a gasp of surprise to see Sago, the steward, quietly aiding his master in his dressing.

“Come in,” was Captain Rodgers’ cheery answer to their inquiry through the half open door. “Why, what’s the matter?” he cried out in alarm after one glance at Phil’s blood-stained face.

Phil stood nonplussed before his captain. Sago turned pale under his parchment-like skin. Before the midshipman could speak, the steward attempted to excuse himself and withdraw, but Sydney barred his way and the two lads entered the room, closing the door behind them.

“What on earth has happened?” Captain Rodgers exclaimed sternly.

Phil saw his reflection in the glass, and the sight caused him to start in alarm. One side of his face was smeared with blood; his coat was open, and inside his white shirt there showed a red blot from the wound on his chest. He knew the hurts were not serious, but his appearance was ghastly.

“We’ve unraveled the whole plot!” Phil exclaimed, not heeding his captain’s inquiry. “Mr. Impey has deliberately misrepresented everything to us. He has fooled the Japanese too, and they have sent Captain Inaba, or at least Impey says so, and Taki corroborates it, to intercept and take the Chinese war-ships.”

Captain Rodgers threw an anxious glance in Sago’s direction. The steward had withdrawn to a corner of the room and was standing with his back to the Americans.

“Impey told us that Sago went to the Minister of War or to some one there and told that O’Neil had the missing secret document,” Phil said quickly in answering his captain’s unspoken question as to the propriety of speaking before the steward. “We can’t blame him though, sir,” he added generously. “After all, his blood is Japanese, and we had no right to the letter.”

Sago’s face beamed with gratitude as he turned toward the Americans.

“Sago very loyal to America, captain,” the Japanese steward exclaimed earnestly, coming forward timidly. “Sago very much afraid when he see the letter. Captain Inaba my old friend. I tell him where is the letter. I very sorry to offend my captain.”

Captain Rodgers looked puzzled. He glanced hastily at his watch. “Go and get yourselves ready,” he ordered suddenly. “We’ve less than an hour. When I am dressed, I’ll come in and you can tell me the whole story. I can’t understand these fragmentary descriptions.”

The lads quietly obeyed, and once in their own room Sydney carefully washed and antiseptically dressed Phil’s scars of battle. The midshipmen were struggling into their evening uniform when the captain appeared, looking very imposing in his gold lace and medals.

The lads began at the beginning and gave him minutely all the important information which they had learned since their arrival in Tokyo, and also a short account of their differences with Lieutenant Takishima which had ended so happily. Captain Rodgers took Phil seriously to task for breaking the anti-dueling rule, but he promised no further action.

“What can be the aim of this fellow Impey?” Captain Rodgers said quietly after he had admonished the lads in his severe stern official voice. “Who will benefit by a war between us and Japan?”

Captain Rodgers sat silent, thinking deeply while the midshipmen, assisted by the grateful Sago, finished their toilet.

“There’s a European country mixed up in this somewhere,” he said half to himself. “That country has a railroad in Manchuria, and is building a new road toward the valuable mining districts of Shensi Province in China.”

Phil and Sydney had stopped in their dressing, and were listening eagerly.

“When the Chinese prince was in America, our bankers closed a loan to the Chinese government of many millions of dollars; for this an American syndicate received a concession from Peking to build a railroad from Amay through Shensi Province. This road will be an outlet for the richest coal, iron, copper and silver mines in China.” Captain Rodgers again stopped and tapped the floor with his foot, a favorite habit when he was thinking deeply.

“A war between the United States and Japan, if Japan were victorious on the sea, would make void this concession. This European country is building without a concession from China, in violation of China’s right to say who shall exploit her resources. Japan victorious, America could not build the railroad; the vast riches of Shensi Province would pass over the railroad of this European country.”

“What country?” Phil asked, unable to control his curiosity longer.

Captain Rodgers smiled knowingly and shrugged his epauletted shoulders.

“If the United States were victorious,” he continued, without answering Phil’s question, “then there would be another part of China which Japan would be forced to evacuate, and this European country would be equally well off. Yes,” the captain added, as though convinced, “that must be the correct diagnosis.”

The midshipmen had drunk in every word of their captain’s able summing up, and now gazed at him eager to hear more.

“Then who is Impey?” they asked almost in a breath.

“He must be that country’s agent,” Captain Rodgers replied quickly, “and probably agent also for the shipbuilding firms who built the Chinese navy and are now wondering where they will get their money, for China is in the throes of internal strife. If these ships are bought by Japan or the United States a very fancy figure would of necessity be paid.

“Sago,” Captain Rodgers added, and the steward bowed low in answer, “remember the United States wishes to be Japan’s friend. Her interests and Japan’s are not really in conflict. It is these interested third parties who are forcing us to be unfriendly and maybe to fight.”

Sago bowed again and drew in his breath sharply in sign of agreement.

“Will you tell me just what was in that letter?” the captain asked.

Sago hesitated several minutes, while the three American officers waited patiently, no sign of intimidation in their attitude toward the uncertain Japanese.

“It said the United States ships in Manila will be ordered to seize the Chinese ships. That United States make law to keep all Japanese out of America and the Philippine Islands. That United States want to capture Formosa. That United States and some European countries want to make Japan give up Manchuria. It then say Japan must quick buy Chinese ships and America would be afraid to make war because Japan then be too strong.” Sago spoke jerkily and slowly, selecting his words carefully while he translated, in his mind, the characters of the secret letter.

“And all of that misinformation came to the Japanese through Mr. Impey and his agents!” Captain Rodgers exclaimed angrily. “What a wonderful imagination Impey must have! And so the Japanese have rushed away to take the Chinese ships to prevent their falling into our hands. How easily an intelligent nation’s suspicions can be aroused. The Japanese diplomats believed that letter was an accurate summing up of the situation, and in reality America has not raised a hand to acquire these vessels.

“To whom was this letter addressed and by whom signed?” Captain Rodgers asked earnestly of the steward, who seemed now only too anxious to give all the information possible.

“Addressed to the advisers of the Emperor and signed by the chief officers of naval and military services,” Sago answered unhesitatingly.

“Captain Inaba is their right hand man!” Phil exclaimed. “He probably composed the letter, and Taki said he knew the contents.”

“Only half of the secret has been unraveled,” Captain Rodgers said thoughtfully. “Impey took his garbled story of the letter to our ambassador. He probably also went to Captain Inaba with the tale that the letter was in the hands of our sailors; Captain Inaba has gone to seize the Chinese ships before our fleet in Manila can intercept them. Impey gave you this information and Takishima has confirmed it.”

Captain Rodgers was silent for a few moments, then a slight smile curved the corners of his mouth.

“Our ambassador sent a cable to the State Department giving the information which Impey brought him,” he said slowly and thoughtfully. “The ‘Shimbunshi’ claims to have received a cable saying our government had determined to take the Chinese ships. I believe the cable was pure fabrication—Impey’s imagination. Still,” he ended abruptly, “I am puzzled to explain all of his actions. At times he impressed me as being honest.”

Phil smiled in a satisfied way. Had he not suspected him from the first?

“The situation is a very grave one,” Captain Rodgers said to the lads, after they were in the carriage and driving rapidly through the streets, illuminated in honor of their visit, on their way to the American Embassy. “When two nations mistrust each other’s actions, the seizing of the war-ships of a neutral and weak power like China is very certain to precipitate a condition which will be a step toward war.”

Phil and Sydney nodded their heads in silent understanding.

“And I am afraid that the ambassador and I are quite powerless to change the situation,” he continued thoughtfully. “The only way possible would be to induce the Japanese government to refrain from this seizure.”

“Takishima said that was now impossible,” Phil exclaimed in much perturbation, for he had not believed the mere seizure of the Chinese ships by Japan would lead to war.

Further conversation was cut short as their carriage rolled up through the smooth driveway to the door of the American Embassy. The lads caught glimpses of much gold lace as they followed their captain into the brightly lighted hallway, where their capes and hats were handed over to numerous attentive servants.

Once in the large reception room, dazzled by the handsomely gowned women and the glitter of Japan’s chivalry, both military and naval, the situation dwindled in importance. Impey was there, and Phil caught his eye almost immediately upon entering the room. The lad’s face flushed and there was anger in his heart as the part Impey was playing came again into his mind.

At dinner Phil was deeply gratified to find himself between Helen and Takishima.

“Is what I heard about Mr. Impey true?” the former asked Phil in a low voice amid the loud hum of conversation about them. “Has he intentionally misrepresented the condition of affairs to father?”

Phil nodded. “Worse than that,” the lad whispered impressively. “He is responsible for all those articles in the ‘Shimbunshi’ slandering Americans. He has fooled both the Japanese and ourselves, and has brought the two countries precious near to a war.

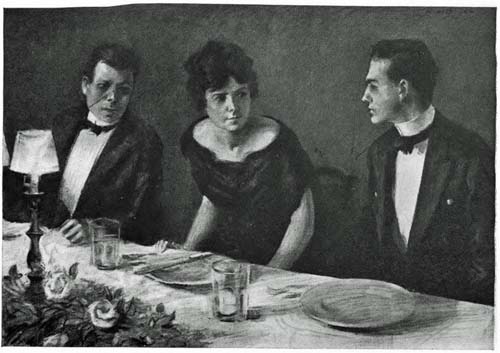

“You wouldn’t think it by looking about this table, would you?” he added in grim humor.

The entire Japanese cabinet and the highest of its naval and military officers, with the officers of the “Alaska,” were seated there in friendly conversation, as if no thought of the horrors that might come had entered their minds. Within a week, if Impey’s plans were successful, these same people might be pitted against each other in a terrible naval battle.

“Does father know this?” the girl asked anxiously. “I thought of telling him what I had overheard at that unfortunate affair between you and Lieutenant Takishima, but I was afraid I had not heard aright, and I was too much agitated afterward to ask you to explain.”

“I shall tell him to-night,” Phil replied, “unless Captain Rodgers does. I have told our captain everything except——” Phil stopped abruptly while Helen raised her eyes to his face in inquiry.

“Except what?” she asked quickly.

“EXCEPT WHAT” SHE ASKED

“Oh, nothing,” Phil began, and then after a second’s thought he changed his mind. Why should he not tell? Every one near them was busy talking and no one could possibly overhear. “Impey said that he had an order signed by the Wai-Wu-Pu, to turn over the Chinese squadron to the Americans, and wanted me to take his yacht, the ‘Sylvia,’ and beat the Japanese ships south. You know that we think they have gone with Captain Inaba to seize the Chinese squadron off Singapore Straits.”

“Why don’t you tell that to father?” she asked.

“Impey assured us that your father already knew of this letter from the Wai-Wu-Pu,” Phil returned.

Before the girl could answer, her neighbor on the other side claimed her attention, much to Phil’s chagrin, and he unconsciously frowned in the direction of Lieutenant Winston, the intruder.

“Our friend Impey has been watching you very closely, Perry,” Takishima said in a low voice as Phil turned away from Helen’s averted face.

“Watching us both, I imagine,” he replied. “A much colored account of our little misunderstanding this afternoon will probably figure prominently in the ‘Shimbunshi’ to-morrow,” he added in concern.

“I’ve seen to that,” Takishima assured him. “The ‘Shimbunshi’ has been suppressed by the prime minister’s order. And all cablegrams from the country are being censored, and nothing can be sent in cipher.”

“I wish you could persuade your minister to recall Captain Inaba,” Phil urged earnestly. “Captain Rodgers believes that if he seizes the ships a war may still be the outcome.”

After the dinner was over Phil and Sydney maneuvered to have a quiet talk with Takishima. A bold plan, the seed of which had been sown in Phil’s mind by Impey’s proposal to use the yacht, had occurred to the midshipman. Phil was not sure the “Sylvia” would be allowed to leave Yokohama harbor, but a word from the Japanese lieutenant would be enough.

Helen was taken into the conspiracy, and with the three classmates quietly stole away to a sun parlor in the back of the legation.

“No one will find us here,” Helen whispered breathlessly, her face showing keen excitement.

Phil, remembering Takishima’s promise to be open and frank with him, began by asking the question that seemed to be the most important to clear up.

“Have your war-ships been given orders to prevent the sailing of the ‘Alaska’?”

Takishima’s eyes opened in mild surprise.

“How could you believe that Japan would be so impolite?” he replied. “Who is responsible for such a rumor?”

“Impey, of course,” Phil returned, smilingly, “the source of all our misinformation.

“But,” Phil persisted, “if the ‘Alaska’ should leave now and send a wireless to the American fleet in Manila to take the Chinese ships, Captain Inaba’s mission would fail.”

Takishima was thoughtful.

“We should not stop the ‘Alaska,’” he said decidedly. “What steps our Minister of Marine would take afterward I cannot say, but of course you know we would take all steps possible to insure Captain Inaba’s success.”

“If you were sure America did not want the Chinese ships, your minister would be willing to have Captain Inaba fail, wouldn’t he?” Phil asked.

“Yes, certainly,” Takishima answered without a moment’s hesitation.

“Impey, as the agent of the builders of these ships, desires them to go to either the United States or Japan.

“That is Captain Rodgers’ opinion,” Phil continued. “The ships were built for China, but as yet not paid for. Impey declares he has in his pocket an order from the Chinese council for the throne, the great Wai-Wu-Pu, to turn the ships over to the American government. If he were not the agent how could he get such an order?”

Takishima shook his head in sign of mystery.

“Cannot we manage to prevent either nation from getting them?” the midshipman asked excitedly. “Then all would be settled amicably.”

“How could we do the impossible?” Takishima asked, his dark eyes sparkling.

“Get this order from Impey. Use the ‘Sylvia’ and take the Chinese ships into Manila Bay,” Phil replied quickly. “Our admiral would look out for them and convey them back to China.”

Takishima drew himself up stiffly.

“What do you mean?” he gasped. “That I should betray my country, and deliver the ships into your admiral’s hands?”

Phil in his earnestness had certainly made a blunder.

“Phil means to put the Chinese ships out of the reach of both nations,” Sydney hastened to explain, and Phil nodded gratefully.

“I can’t see how that can be done,” Takishima replied, after several minutes’ thought. “I am very sorry, but as a Japanese naval officer I cannot take any action that would defeat the aim of the Emperor. His Majesty has made his decision; that decision cannot be changed.”

“Then you refuse to help us to avert this war!” Phil exclaimed.

“There is nothing else honorable for me to do,” Takishima answered.