CHAPTER XII

SMUGGLED ARMS

AS the Americans had ridden their ponies through the throngs of natives in the street of the town of Saluafata, the cheery “Talofa, Alii” had been conspicuous by its absence. Instead Phil’s interested glance was met upon all sides by haughty and sullen stares from the dark-eyed natives.

“They’re up to some mischief,” O’Neil whispered, “and they don’t like our being here. That’s sure.”

The road or street led now along the sea beach. The schooner “Talofa” lay anchored a few hundred yards distant. Nearly a dozen long narrow-flanked war canoes hovered near or alongside.

“Guns,” Sydney exclaimed excitedly. “Look, they are being passed down by hand into those boats alongside.” One very large canoe manned by nearly forty naked savages had just shoved off from the schooner. Its crew was singing a stirring song, keeping perfect time with their paddles as they propelled the canoe slowly down the beach.

“They’ve blackened their faces,” O’Neil declared anxiously. “You know what that means?”

Phil nodded, his heart beating rapidly, and a thrill passed through him at the thought. To blacken the face was a declaration of war.

“Ride straight on,” Phil commanded, as they suddenly made a turn, in following the street which now ran at a sharper angle toward the beach, and saw before them Klinger and the count surrounded by natives in chief dress. “I can see the British launch. She’s just at the reef near the entrance to the harbor.”

“There’s Kataafa himself,” O’Neil exclaimed excitedly in a low voice. “The old man with white hair and moustache.”

The midshipmen gazed upon him in awe mixed with admiration. They had not seen him at such close range before. They saw a man straight and sturdy, despite his sixty odd years of age. His countenance was not fierce as they had expected to find it, but instead benevolent and kingly. Every other face turned toward them showed upon it only too plainly distrust, anger and resentment, but the high chief Kataafa alone simply smiled a welcome and as they drew near said “Talofa, Alii, Meliti.”[31]

All three horsemen doffed their caps.

“Talofa, Alii, Kataafa,” Phil returned.

“Call up the boat, O’Neil,” Phil said; his voice was unsteady. “Say Kataafa has guns, and warriors have blackened their faces.” They were now on the sandy beach close to the water.

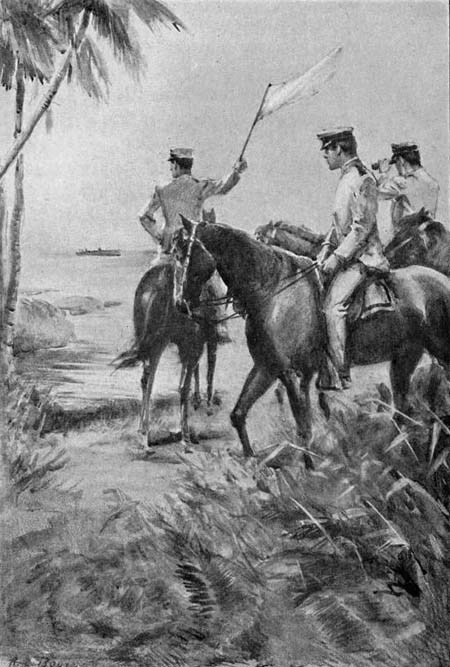

O’Neil drew from his stirrup leather the red wigwag flag which he had brought along for the purpose of sending news quickly back to Ukula by the steam launch. He began at once to wave it over his head and scarcely a second elapsed before a similar flag appeared in the bow of the tiny launch nearly a mile away.

“They were on the job,” Sydney exclaimed, while O’Neil went to work rapidly to send the signal given him a moment before by Phil.

HE BEGAN AT ONCE TO WAVE IT

“Sent and received, sir,” he reported as he flourished the flag in a farewell signal and then calmly rolled it up, sticking it back into his boot leather. Then for the first time the sailor noted the menacing attitude of the people about them.

A woman’s voice was calling them from the edge of the crowd. She was endeavoring to reach their side.

“Missi Klinger say you better ride back quick,” she cried, her handsome face ashen with fear for the papalangis. “Come quick with me; it might be death to stay longer.”

Fanua put forth her most eloquent English. She had been educated at the mission school, but like most natives was shy in speaking a foreign language. She had taken Phil’s bridle rein, and now led his horse through the crowd while the other two followed.

“They won’t harm us,” O’Neil declared comfortingly, although he did not believe his own words. “The signal has roused their distrust of us, that’s all.”

“We’re spies,” Sydney exclaimed. “Is it unnatural for them to wish to harm us?”

“There’s no war, sir,” O’Neil said, “so we can’t be spies. And besides, we’re in uniform.”

“Then under the laws of war,” the midshipman replied, “they can take us prisoners.”

“The news will get through just the same,” O’Neil said gladly, “and Commander Tazewell will have warning in time to carry out whatever plan he has decided upon.”

Klinger had left his companions and had advanced to meet the returning Americans. He walked beside Phil’s horse, while Sydney and O’Neil pushed forward their ponies to hear. The manager’s face was the color of his white clothes.

“Don’t stop,” he warned anxiously. “Even the king Kataafa could not hold his people if a fanatic should raise the cry to kill you.”

Phil did his best to look haughty and unconcerned, but he could feel his knees tremble against his pony’s flanks.

“You’ve started your war, I see,” he mustered his voice to say, endeavoring to put into it a note of scorn and defiance.

Klinger did not reply to the accusation.

The Americans were not slow to obey Klinger’s directions. Count Rosen scowled darkly as they passed him. The chiefs gazed upon them with angry eyes. Even Kataafa no longer wore his welcoming smile, but his eyes were still mild and kindly. To Phil’s surprise the high chief fell into step alongside his pony and trudged silently beside them; the other chiefs closed in after O’Neil and quietly followed. Fanua, the native woman, darted back to her house, upon the steps of which the count was left alone.

Upon reaching the top of the hill, Kataafa and his chiefs stopped while the high chief waved a dignified salutation. “Talofa, Alii,” he said. Klinger went on a short distance farther. He had by this time regained his self-control. The danger had passed.

“Tell your captain,” he said earnestly to Phil, “that Kataafa has nearly every native in Kapua on his side. Tell him I say don’t let the English throw sand in his eyes. He has the one chance in his career to do something for his country. If he throws over the English and supports us, Tua-Tua and the island of Kulila might be given to America, and Kataafa will be king without bloodshed.”

“I know nothing of my captain’s plans,” Phil replied distantly, “but I will deliver your insulting message. I hope to be able,” he added still haughtily, but with a forced smile, “some day to repay your civility to us in Saluafata.” He saluted stiffly and put his pony to a trot.

The Americans trotted their steeds until the little animals were breathing heavily from their exertions. Then Phil allowed his pony to walk. They were passing through a native village. Beyond the reef the first of the war canoes was in sight, and an occasional shout from an overwrought warrior as he paddled came distinctly to their ears. A curl of smoke at the entrance of Vaileli Bay in the general direction of Ukula marked the progress of the returning steam launch.

It was nearly two in the afternoon before Phil and his party reached town. In the road before the British consulate they saw drawn up a company of British sailors, while on the lawn others were setting up their white tents. The British captain and his consul hailed them from the porch.

“We were getting worried about you,” he called, waving a greeting. “You see we’ve acted upon the information you secured.”

Phil stopped and told the Englishmen briefly what they had seen, and then continued toward the landing.

Alice Lee spied the horsemen and ran out joyfully to meet them.

“I began to be frightened,” she owned. “I am deathly afraid of a Kapuan when he blackens his face.”

Phil could now smile easily, but he acknowledged that the sensation of being surrounded by a swarm of excited warriors, bent upon war, had not been a pleasant one.

The midshipmen were brought into the consulate, while O’Neil continued to the landing. He had caught sight of the American sailors marching up the road, and as he was in the landing detail, he feared some one might replace him unless he returned to claim his rights.

Commander Tazewell and the consul were on the porch, and the consul’s daughters, looking slightly pale over the exciting news brought by the steam launch, which had arrived an hour earlier, led the newcomers forward to tell their story.

“The chief justice gave his decision a very short time after you left town,” Alice told them breathlessly. “The news was taken to Kataafa by a fast canoe. I watched it from my ‘lookout’ until it went inside the reef off Vaileli.”

“Kataafa and Klinger must have known it when we saw them, then,” Phil said to Sydney. “Klinger thought we knew it, too; that’s why he gave us the message.”

“What was it?” Alice asked eagerly, overhearing Phil’s aside.

“To cut loose from the English and join his country in supporting Kataafa,” Phil told her. “He would like to see America disregard the chief justice’s decision.”

“That looks as if Klinger and his crowd were worried over the outcome,” Alice said thoughtfully, while the midshipmen nodded their heads in agreement.

Mr. Lee seemed very uneasy while Phil as spokesman gave a minute account of their ride to Saluafata. He told of the hostile attitude of the warriors and Klinger’s fears for their safety, and he spoke admiringly of the old high chief Kataafa, who had acted as their personal body-guard until the edge of the town had been reached. Phil also did not hesitate to deliver Klinger’s message which he had haughtily scorned but agreed to repeat to his captain.

Commander Tazewell listened gravely, but to outward appearance was unmoved.

“Klinger has shown us his game,” he said after Phil had ended.

The midshipmen would not accept the invitation to stay longer. They were hungry and dusty after their long ride, and pined for a bath and clean clothes.

As they proceeded toward the boat landing, they gazed admiringly at their sailors, pitching tents, erecting shelters and making all arrangement for a protracted stay on shore. Lieutenant Morrison stopped them to hear the news they had brought from the Kataafa camp. The lieutenant was in command of the American sailors landed to protect American lives and property that would be in grave danger when the rebels attacked Ukula. Ensign Patterson, a big raw-boned young man, with a happy, irresponsible disposition, but greatly loved by all for his generous nature and rash fearlessness, was Lieutenant Morrison’s assistant. He waved a joyful greeting from a mass of luggage, the assorting of which he was busily directing.

“It certainly looks like business,” Sydney exclaimed as they left the busy scene behind and arrived in sight of the landing, where they found a boat was awaiting them.

They did not tarry long on the ship, but were soon again on their way ashore.

As the midshipmen passed again through the American camp, half-way between the landing and the American consulate, they espied O’Neil’s soldierly figure mustering the guard to be posted for the protection of the west end of the Matautu district of the town. The English sailors were guarding the eastern end.

The boatswain’s mate brought his men to attention, and gravely saluted the passing young officers.

Lieutenant Morrison and Ensign Patterson were inspecting their position. A Colt gun commanded the main road and another the road leading inland along the Vaisaigo River. Temporary barricades were being built back of the camp, facing the bush, behind which a stand could be made if by chance the attack should come from that direction. This, however, was unlikely, owing to the dense underbrush and the boggy soil.

Phil and Sydney greatly envied the officers with the sailors. They were sure that there would be fighting soon, and very much feared that they would find themselves out of it. However, Commander Tazewell had shown the midshipmen that he trusted them and was willing to give them hazardous and important duty, and they had reason to congratulate themselves that the duty had been performed to their captain’s satisfaction.

“What about Captain Scott and the ‘Talofa’?” Sydney suddenly asked. “I thought the captain was bent upon capturing him.”

Phil shook his head. “I suppose he figures there are more important things for us to do than to chase the ‘Talofa.’ He’s landed his guns and gotten away by this time. Stump is still on board the ‘Sitka,’ eating his head off.”

“Captain Scott certainly played his game well,” Sydney declared. “He’s a Yankee, all right. No one else would have been able to get so handily out of the mess occasioned by Stump’s navigation.”

At the consulate they found only the consul’s daughters.

“They are having a meeting to decide what is to be done,” Alice told them. “The new king Panu-Mafili and his chiefs just came to ask protection. They have scarcely five hundred warriors, and Avao says many of those are disloyal, and all their guns are old and rusty. They bury them, you know, during peace, so they won’t be stolen.”

“Imagine that,” Phil exclaimed, “and in this damp soil. But where’s the meeting?”

“At the house of the chief justice. The Herzovinian consul sent word he was ill and couldn’t attend,” Alice replied. “Of course that means he won’t agree with anything we decide to do.”

The meeting apparently did not last long. The midshipmen saw the young king, accompanied by several chiefs, among them the loyal Tuamana, in company with Mr. Lee and Commander Tazewell, approaching. At the consulate gate the natives solemnly bowed and departed.

“Kataafa has sent in word,” Commander Tazewell told the lads, “that he will enter Ukula and reëstablish his government at Kulinuu. The king, Panu, desires to abdicate to prevent fighting, and has asked our advice.”

“And we advised him to yield,” Mr. Lee added.

“There’s nothing else we can do,” Commander Tazewell said sorrowfully. “If we had sufficient force we could support him, because he is the rightful king; but two hundred sailors are not enough to hold the town, much less be able to seek for and attack the rebels, numbering many thousands and all well armed with new and modern rifles.”

“Then there will be no fighting after all,” Phil exclaimed. And the evident disappointment in his voice caused a general laugh.

Commander Tazewell shook his head. “Some of the chiefs, among them Tuamana, declared they would not submit, and would defend Kulinuu, but I believe when they find themselves outnumbered their ferocity will subside. We shall guard the Matautu district, and I’ve sent word for all peaceful people to come here for protection.”

The midshipmen were further told by their captain that Mr. Lee had given over a wing in his big house, and he was sending word to his steward to bring over a hand-bag of clean clothes, so the midshipmen scribbled a note to one of their messmates to send along a valise full of necessities.

“It will give my daughters and myself,” Mr. Lee said gratefully, “a feeling of great security to house you under our roof, and I hope we can make up in our hospitality for the lost comforts you enjoy on board ship.”

Phil and Sydney exchanged amused glances. Their little two-by-four cabin compared to a big, airy bedchamber on shore was certainly funny.

The Herzovinian sailors that had been landed to guard Klinger’s store were now reënforced and camped near their own consulate in the Matafeli district of the town. A flagpole had been erected, and the Herzovinian flag floated alongside the Kapuan standard not far away at Kulinuu.

“One’s afraid and the other dare not,” Sydney exclaimed as he and Phil lounged luxuriously in the capacious wicker chairs in their big bedroom. “Herzovinia thinks she isn’t strong enough to back Kataafa openly and we know we are not numerous enough to resist him.”

“I don’t think the native enters into the question, really,” Phil declared. “You see, Syd, a fight in which the white people might be arrayed on both sides would certainly mean a diplomatic rupture at home. That’s what the consuls and naval commanders are trying to avoid. Herzovinia is deeply involved in this game. Commander Tazewell hasn’t said so, but I believe he thinks that Count Rosen is really a diplomatic agent sent here to create an intolerable situation. His government is tired of this triumvirate control and wants to own Kapua herself.”

“I wish the English and Americans had taken the bull by the horns and sent word to Kataafa that if he attacked Ukula they would fire him out by force. I don’t believe then he would dare attempt it.” Sydney’s eyes flashed.

“Those natives we saw to-day,” Phil replied, “didn’t look as if they could be so easily intimidated. I believe the decision made is the best. We have a big cruiser coming with an admiral on board. When she arrives we may have strength enough to uphold the decision of Judge Lindsay. One nation has broken the treaty. Consul Carlson, in refusing to help the other two consuls to uphold the decision, has shown that he is partial to Kataafa.”

At dinner that evening nothing but Kapuan affairs could be discussed. No one thought of anything else. The district of Matautu appeared like an armed camp. Hundreds of natives had arrived for refuge, bringing in all their valuables. The balmy air reeked with cocoanut oil, and the musical songs of men and women as they squatted under their hastily constructed shelters were heard on every side. The terrors of war rested lightly upon their childlike minds. To them war was only a festival, an occasion for song, dancing, kava drinking and visiting.

Before eight o’clock that evening many wild rumors were brought into the camp by the women. Some of the refugee women had husbands on one side and some on the other. Among the Kapuans, women are neutral, and are free to go freely between the hostile camps.

Alice and the midshipmen mingled with the natives in order to gather all the news brought in. All indications showed that Kataafa would be as good as his word, and would attack that night.

The first part of the evening, however, dragged on and everything seemed quiet in the direction of the native town and Kulinuu where a few hundred loyal natives had undertaken unaided to uphold the rights of their chosen king against the attack of the rebel hordes.

Suddenly the startling rattle of musketry drifted down on the light breeze from the other side of the bay. Shouts and cries of defiance and anger could be distinctly heard through the still night air. Kataafa had broken his sworn pledge made solemnly and in writing never again to resist the constituted authority of Kapua. Three hundred odd sailors of three great nations listened to the raging of the unequal struggle. Among savages, might is always right. There was no doubt who would be king of Kapua when the day dawned, Judge Lindsay and the treaty notwithstanding.