CHAPTER XVI

CARL KLINGER

AVAO appeared at the consulate one morning a few days after the count’s Siva-Siva dance, her black eyes bright with indignation.

“See,” she exclaimed as she handed to Alice a sheet of paper on which was printed a dozen or more lines.

Alice read slowly, the color mounting to her cheeks and her breath coming faster.

“They have confiscated all of Tuamana’s land,” she exclaimed, “and branded him a rebel to the king. This is the official notice posted about the town.”

Phil, in spite of the evident seriousness of this act to the native girl, could not suppress a smile.

“Kind of mixed up affair, isn’t it?” he said quietly. “Rebel Kataafa brands the loyal Tuamana a rebel.”

“This is Klinger’s work,” Alice declared. “The land is most valuable, cocoanut and banana groves, and worth a dollar a tree every year for the copra alone. There must be over a thousand trees on the land. It’s a fortune, and it is all that Tuamana’s family possesses.”

“Can nothing be done?” Sydney asked solicitously. “Where is it located?”

“Let’s go and look it over,” Phil suggested, “if it isn’t far away.”

The horses were quickly saddled and the four were soon on the way to visit the family estate of Tuamana, chief of Ukula.

It was near the sea beach, to the eastward of Matautu. As they approached the cocoanut grove they beheld a number of black boys[35] running barbed wire through new fence pales, recently set up.

“They are fencing it off already,” Alice exclaimed as they halted their ponies.

Avao pushed her pony across the wire that had not as yet been stretched, calling to the others to follow. Very soon they arrived in front of a very large native house. Several women sitting within quickly arose and greeted them.

Avao talked with them for several minutes.

“My relatives say that Missi Klinger has ordered them to move their house; that it is on the Kapuan firm’s property,” Avao said, her voice breaking in mortified anger.

They had all dismounted and several of the native men had climbed trees to gather fresh cocoanuts for their visitors.

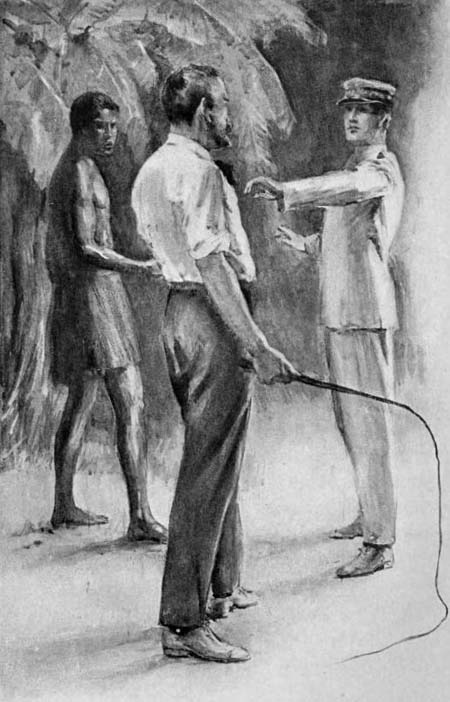

Suddenly a cry of alarm was raised, and one of the young natives slid quickly down the tree and dodged off into the bush. Phil and his friends had just reached the house when they heard a hoarse cry of anger, followed by a loud report as of a pistol discharge. Phil hurriedly moved until he could see between trees that the other native was standing at the foot of the tree into which he had climbed, and that Klinger was beating him with his slave whip. The native was silent, stoically accepting the punishment from the white man, while yet in his hands were several green cocoanuts he had just gathered.

“Who is the native boy?” Phil asked of Avao. He saw her lips were trembling.

“My cousin,” she said.

Phil, acting upon a strong impulse to protect the native, who had been acting in his own service, turned and rapidly approached the brutal scene.

“Mr. Klinger,” he exclaimed tensely, “you will please stop whipping that native at once. It’s outrageous. What has he done to deserve such punishment?”

With his whip hovering over the bruised back of the native, Klinger gazed angrily at the intruder.

“This is my method of punishing these rebels who steal my fruit,” he replied, and then the cruel whip again fell upon the native’s quivering back.

“Stop it, I say!” Phil cried determinedly. “I shan’t stand idly by and see you maltreat that poor fellow. He was gathering his own fruit for us to eat. You are the one who is stealing other people’s fruit, and what’s more,” and Phil’s voice rose high in indignation, “if you don’t get off of this place and take your slaves with you, I’ll whip you with your own rawhide.”

“YOU ARE SIMPLY A BULLY”

Klinger’s hand dropped to his side in sheer dumbfounded amazement. He gazed in bewilderment at this young man, not able to realize that such words had been addressed to him.

Phil made a sign for the native to go, and the stolid but mystified native smiled in his pain and moved out of reach of the whip.

“Now go,” Phil commanded to Klinger. “This place is private property, and you are trespassing.” He pointed the way out.

Klinger slowly recovered his balance. Then a sinister smile spread slowly over his face.

“I can show you that you and your friends are the trespassers,” he said evenly. “Here is my title to the property, signed and executed by the court.” He drew forth a paper from his coat pocket.

Phil gazed squarely into Klinger’s face unwaveringly. “You heard what I said,” the young midshipman replied. “I saw the way you horsewhipped that inoffensive native; if I were he I would wait my chance and give you back two blows for every one received. You are a brutal coward! Your kind don’t fight. You are simply a bully!”

Klinger, fairly aroused, was now stung to action; again he raised his cruel whip, slinging the long lash behind him and retreating a step to give the blow fair play. Phil did not budge. He saw the long leash raise itself as if alive from the ground; he heard it sing in the air above him, expecting it to wrap itself stinging and biting about his neck. But it passed harmlessly a few inches from his shoulder and fell upon the ground at his feet with a dull report. Then he could hardly believe his eyes, for his antagonist was rolling on the ground, a naked brown body clinging desperately to him.

Phil was transfixed in astonishment. His first intention, to go to the aid of the native, he saw was unnecessary. The supple native boy had found his strength and was slowly choking the breath from the manager’s body. Klinger’s face had turned purple before Phil could persuade the injured native to desist. The boy was fairly delirious with savage joy over his wonderful achievement. Klinger lay insensible upon the ground. Phil stooped, the manager’s whip in his own hands, and tore the man’s shirt at the neck and felt for his heart. He feared that some permanent injury might have been done him.

Sydney and the others were now at Phil’s side. Avao openly praised the native boy for his prowess, and Phil learned that a command from her had sent this young bundle of steel muscles to protect him from the manager’s cruel whip. The native grinned for joy. He had discovered his own manhood and protected a papalangi friend of the queen of his clan from a ruffianly slave driver.

“He’s nearly choked to death,” Phil announced as he rose to his feet. “That boy has the strength of a young gorilla in his hands. Look at those marks on Klinger’s neck.”

The manager’s neck was a sorry sight; the cords and muscles had been twisted and almost pulled bodily from the broad throat.

“He’ll have an awfully sore throat when he wakes up,” Sydney said quietly.

“We must get him to a doctor at once,” Phil exclaimed. “Avao, call to those slave boys. We must have him carried to town.”

The Tapau called, and several of the blacks started toward them.

Then Phil thought of the native boy who had come to his aid. He feared for him. He knew that some cruel and unheard-of punishment would be given to the native that dared to so roughly handle the manager of the Kapuan firm. Death even was not impossible, especially as the native was a relative of Tuamana.

“Avao,” he whispered, “tell the boy to go away far and not come back until you send him word.”

“He knows, Alii,” Avao replied. The boy pressed his forehead hurriedly to the girl’s hand, and then murmuring, “Tofa, Alii,”[36] with a cheerful grin vanished into the “bush,” just as the first of the Solomon Islanders arrived to raise their fallen master.

With Klinger carried on the shoulders of several black boys, and with the Americans bringing up the rear, the party proceeded toward the town.

Fortunately a carriage was hitched at the British consulate and the driver sitting in the shade near by. They put Klinger inside, while Phil and Sydney remained to support him, and thus they drove hurriedly to Klinger’s residence back of the store.

“This isn’t going to improve the kind feeling between us and the ‘de facto’ government,” Phil said.

“I’m glad you are not responsible,” Sydney declared.

“But I was,” Phil insisted. “I goaded him on to strike me. I had an irresistible desire to take his whip and give him a plentiful taste of his own medicine. He would have struck me, too. I saw it in his eyes. He has an ungovernable temper, and was clean off his head.”

“Why will you be so rash?” Sydney asked affectionately. “Some day you’re going to get into serious trouble.”

“I can’t help it, Syd,” Phil answered soberly. “Such acts as that, beating an inoffensive native, make my blood boil, and I’m thankful I have the courage and strength to interfere. You would have done it too, Syd,” he exclaimed, “if you had seen it before I did.”

Sydney shook his head. “No,” he replied. “My blood is more sluggish than yours. You did exactly right though, Phil.”

Phil was silent for a moment. Klinger’s face was now regaining its color, but his body was still limp and his eyes closed.

“Syd,” Phil said quietly, “you are really more solid than I. You reflect before you act. I too frequently act upon impulse without reflection.”

“You act, though, only upon good impulses,” Sydney replied.

The carriage stopped in front of the Kapuan firm’s store, and a couple of bystanders were impressed to carry the injured man inside.

“Go tell the ‘fomai,’” Phil instructed a native woman, and she departed quickly to obey.

“Shall we wait?” Phil asked nervously. This part of the ordeal was trying for the midshipman.

“I guess we must,” Sydney replied. “We shall have to explain how it happened.”

Phil frowned. “I’m not going to reveal the identity of that native boy. Maybe Klinger did not recognize him.”

The manager had been carried into his own room, while Fanua, his native wife, hovered over him anxiously. She gazed in open distrust upon the two officers.

“Here comes the little doctor,” Sydney exclaimed in relief, as the same fat, middle-aged man that had before restored the injured Klinger after his earlier encounter with Phil pushed his way through the crowd of inquisitive natives, and entered the room.

Klinger had opened his eyes. The pain in his throat made him cry out weakly.

The doctor examined the injured man’s neck in silence.

“A black boy run ‘amuck’[37]?” he asked after he had finished the examination. “It looks as if a whole gang had risen against him.”

Klinger tried to speak, but his voice failed.

“We’ll leave now,” Phil returned. His nerves were under tension. He felt no sympathy for Klinger, yet wished to avoid a disagreeable scene with the injured man. “I shall be ready to give my story whenever it is asked for. Good-day, sir.”

Sydney followed Phil from the room.

“It’s a relief to get away,” Phil declared.

They went at once to the ship and told their story to Commander Tazewell.

“That isn’t the only land grabbing the Kapuan firm has been indulging in,” he informed them. “Our lease of land at Tua-Tua in Kulila has been declared illegal by Kataafa and affirmed by the acting chief justice, Count Rosen. The Kapuan firm, I hear, brought in evidence of a prior claim of purchase. Of course it’s a trick, but we can’t prove that before an interested judge.”

The midshipmen drew in their breath in surprise. Evidently the land grabbing was not confined to property owned by uninfluential natives.

“I have searched all morning,” the commander exclaimed annoyedly, “for the lease signed by Moanga, the chief of Tua-Tua, who owns the property. I took it from the safe yesterday and thought I had returned it there, but it is not in the regular envelope. Probably it is only mislaid, and I shall find it among my other papers. I’m afraid I’m getting careless. A natural effect of this torrid climate.”

“Are you going to dispute the claim?” Phil asked.

“That was my intention,” Commander Tazewell replied, “but the lease is a private one between Chief Moanga and myself. It must be confirmed at home before money is appropriated. Of course I acted under instructions from the Navy Department. It’s embarrassing not to find the paper, because I cannot register an appeal very well without it.”

“Do you believe it has been stolen?” Phil asked earnestly. His thoughts had gone to the orderly Schultz.

“That isn’t likely,” the commander said, shaking his head. “No one has access to my cabin while I’m not here except a few trusted men who keep it clean, and my orderlies, and all of them are men with excellent records. No,” he added certainly. “It’ll turn up; it’s probably in a wrong envelope, and I’ll find it after more search.

“So Klinger has again come to grief through you,” he said to Phil suppressing a smile of gratification. “I am glad you did not carry out the threat you made. I wouldn’t care to have my officers engage in fights with civilians. It doesn’t look well outside, even though it may have been justified.”

Phil acknowledged the mild rebuke.

“I know I’m too hasty,” he said humbly.

The next day news came from ashore that all the male relatives of Tuamana had been arrested for the assault on Klinger and thrown into jail. The house the midshipmen had visited the day before had been demolished by order of Klinger, and the women turned off the place.

Alice was keyed to a high pitch of excitement when the lads saw her in the afternoon.

“They tried to arrest Avao, too,” she exclaimed, “but she ran away and managed to reach the consulate, where they dared not touch her. All the land belonging to Panu’s family in Matafeli has been claimed by Klinger for his firm,” she told them almost in a breath. “Where will it all stop?”

“It won’t stop,” Phil replied savagely, “until the present outfit are put out and the legal government is put in. The treaty is being violated right and left. I can’t see what this man Count Rosen expects to gain by it. The three great Powers when they hear what is going on down here must decide that the high-handedness of Rosen and Klinger have only made things more difficult to adjust.”

“Maybe that’s where the count expects to gain,” Alice said seriously. “Maybe their country wishes to make difficulties—to show the other nations that three countries cannot together run one little group of islands without war and bloodshed.”

“I, for the life of me,” Sydney declared, “cannot see why the United States and England don’t pull up stakes and leave the islands to Herzovinia. I know we have our eyes on the fine harbor of Tua-Tua, but I can’t see when we are going to use it.”

“Maybe you can’t see!” Phil replied sarcastically, “and one reason you can’t see is that you haven’t given it a minute’s thought. Herzovinia has a body of intelligent men in her government whose duty it is to study such questions. It is quite evident those men have advised their nation to endeavor to acquire Kapua, and this is her way of trying to acquire it. The captain of the British war-ship told us the other day that he had seen their machinery of annexation work over in Africa.

“First comes the merchant, pushing his way in by brute strength and awkwardness, shoving out all other merchants by staying close to his job. Then a row between the merchants and the natives, followed closely by the arrival of a war-ship. Then a punitive expedition against the natives who have dared to resent the oppression of the merchants. Then diplomatic correspondence assuring other nations there is no thought of acquisition of territory and then all of a sudden up goes the Herzovinian flag, and the thing has been accomplished. As I said before,” Phil ended his impromptu speech, “I can’t see why the count hesitates about hoisting his flag. We can’t stop him. We haven’t men enough.”