CHAPTER XIX

A REËNFORCEMENT

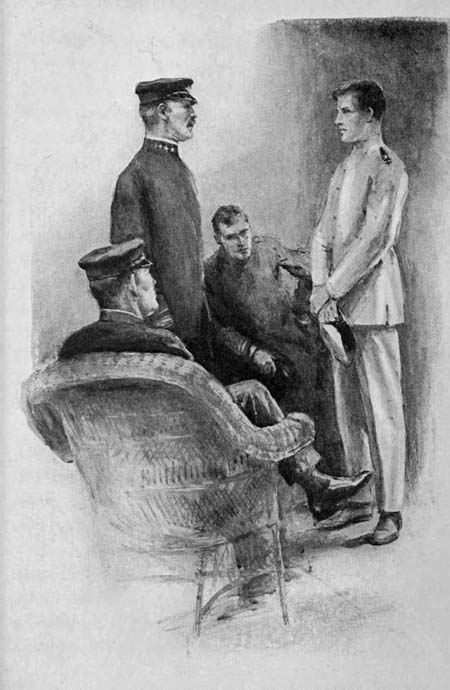

REAR ADMIRAL SPOTTS, whose flag was flown at the masthead of the cruiser “Sacramento,” wasted no time in drawing from Phil the complete story of everything that had happened in Kapua.

The captain of the flag-ship and the admiral’s flag-lieutenant were both present in the cabin and followed the lad’s narrative with great interest and amazement.

Phil told of the decision by the chief justice for Panu-Mafili, and then the attack upon Ukula by Kataafa and his warriors, armed with guns purchased apparently from the Kapuan firm, of the appointment of Count Rosen as governor, and the appeal for annexation to Herzovinia.

“I think I can now see,” the admiral declared, “why the Washington government sent a revenue cutter post-haste from San Francisco to Honolulu to order me to proceed with my flag-ship to Kapua. A great wrong,” he added earnestly, “has been done the treaty, and my duty is clearly to set it right, by force if necessary. I shall consider this Count Rosen an adventurer.

“Yet,” he said after a few thoughtful minutes, “you say the count is prepared against my coming. When those of the ‘de facto’ government see our ship approaching, they are ready to take the responsibility of hoisting the Herzovinian flag over Kapua. Then I shall be powerless; only an order from Herzovinia can remove the badge of annexation. What we do after that will not be an act against the government of Kapua. It will be against the sovereignty of Herzovinia.”

A plan had suddenly flashed through Phil’s mind. The admiral was quick to see the sudden eagerness in the midshipman’s face. A kindly smile spread slowly over his own grizzled countenance.

“You have something rash and daring in mind, I am sure,” he said, half in amusement, but half seriously. “You have the local color and inspiration of contact. Tell us your plan.”

“IS IT QUITE CLEAR?” THE ADMIRAL ASKED

The humor of the situation suddenly struck Phil, and he blushed to the roots of his hair. “Pardon me, sir, for being so bold,” he replied apologetically. “The same thing must have also struck you, sir, and that is the ‘Sacramento’ must enter Ukula harbor at night and secretly and Commander Tazewell must meanwhile prevent the hoisting of the Herzovinian flag.”

All three of his hearers gave an ungrudging assent. The admiral took out his watch. “It’s now a little after one o’clock,” he said. “We are thirty odd miles from Ukula. You can probably be there by dark. I’ll enter the harbor at ten o’clock to-night and shall have my entire force of three hundred men ashore within ten minutes after we anchor. Tell Commander Tazewell I shall leave all details to him, for he knows the situation better than I. Tell him my decision is to uphold the law of the chief justice under the existing treaty until our government orders me to do otherwise.”

Phil thrilled with joyful excitement as he listened to the admiral’s quiet but decided voice.

“Is it quite clear?” the admiral asked.

“Perfectly, sir,” Phil assured him.

“Then I must speed the parting guest.” The admiral smiled, and put out his hand.

Phil shook the hand warmly.

“Happy is he who brings young men to his council table,” the admiral quoted.

With Phil on board, the “Talofa” lost no time in squaring away for Ukula. The “Sacramento” was seen to turn and head out to sea, so as not to be in danger of discovery from shore. Phil told the plan to his shipmates.

“That’s a corker!” O’Neil exclaimed gleefully. “There’s just one thing you haven’t mentioned,” he added seriously. “They’ll see the ‘Sacramento’ coming in from the pilot station and maybe from Mission Hill. The Herzovinian war-ship will also be on the lookout.”

Phil nodded. “Yes,” he said questioningly.

“Then, sir,” the sailorman declared, “we must prevent those at the pilot station sending the news, and blind the other two. A couple of our men can fix the pilot station, and our search-lights can do the rest. They can’t see the cruisers with those big glims in their eyes.”

“Fine suggestion, O’Neil,” Phil exclaimed. “I’ll certainly give it to the captain. And by the way, I have a thought,” he added eagerly, as the “Talofa” raced toward the distant land, all sails spank full and sheets straining. “We’ll get on board the launch, leaving the ‘Talofa’ outside to come in later after dark. It will create less curiosity. Stump and a couple of men can hold her.” He looked at Sydney questioningly. “I reckon, Syd,” he said apologetically, “you’ll have to miss the fun on shore and stand by the schooner.”

Although the midshipman felt somewhat disappointed he did not show it.

“That’s natural,” he said. “I’ll bring her in after dark, all right, and be in time in case there’s a row.”

They found the steam launch awaiting them about fifteen miles from the harbor, and quickly transferred to her all but Sydney, Stump and two sailors, who remained to sail the schooner into Ukula.

“Don’t pile her on the reef,” Phil cautioned banteringly, as the steam launch shoved off from the “Talofa’s” side and headed at full speed for Ukula.

“We should be in by five o’clock,” Phil said as he looked at his watch. “Now,” he added, “these are going to be exciting times, eh, O’Neil? I wonder what’s coming out of it all?”

“It looks as if that count was getting cold feet,” the boatswain’s mate replied. “If he’d had more nerve the Herzovinian flag would have been flying on the flagstaff at Kulinuu right now.”

Phil shook his head. “It’s a pretty big undertaking to annex a kingdom unless you are sure you’re going to be backed up,” he said.

“It didn’t take our admiral long to make up his mind,” O’Neil reminded. “And he doesn’t know he’s going to be backed up, either.”

“That’s different,” Phil replied. “He is only restoring a king to a throne under a law that he considers yet binding. And he has sufficient force to do it.”

Chief Tuamana had shown evident and outward signs of great joy when Phil told him that the American admiral was going to uphold the chief justice’s decision, and passing a big Kapuan canoe filled with natives, the delighted chief raised his voice to taunt his enemies, some of whom he recognized, when Phil by main force drew him down and told him forcefully to keep his counsel to himself.

“They’re just like schoolboys with a secret, sir,” O’Neil said. “Those natives are on their way home, aren’t they?” he asked of Tuamana. The launch was not over three miles from the harbor. The “Talofa’s” sail was barely in sight on the horizon.

The chief shook his head.

“Going to Vaileli for a dance,” he answered in very broken English. “Chief Tuatele is there in that boat; he ask me to go along. He make fun of me.” The chief grunted in contempt.

“Do you mean there’s going to be a big Siva-Siva there to-night?” Phil asked eagerly.

Tuamana replied in the affirmative. “This day big day at Vaileli plantation. Very big ‘Siva-Siva’ and ‘Talola.’”[38]

As they drew nearer the harbor they saw large numbers of war canoes filled with natives, all dressed in gala attire, paddling out through the break in the reef, confirming Tuamana’s information.

“That’s a lucky stroke,” Phil exclaimed. “Probably the count and Klinger will both be at the Vaileli plantation, and if so, there’ll be no trouble carrying out the admiral’s plan. I’m going to find out for sure,” he added as an extra large canoe holding nearly forty men and women passed them, its crew shouting and singing in high glee.

“Run up close,” Phil said quietly to O’Neil. Then to Tuamana, “Say nothing of our plans,” he cautioned, “only find out what’s actually going to happen.”

The canoe paddlers stopped their efforts and waited. Twoscore eager smiling faces were turned upon the Americans, and from all the musical greeting of “Talofa, Alii” was given.

Tuamana rose and with solemn dignity spoke to the people in the canoe. He was answered by an elderly warrior sitting in the stern of the canoe. Both Tuamana and the Kataafa warrior addressed maintained a haughty but dignified bearing toward each other.

Finally Tuamana nodded, and the old patriarch gave a command. The song again broke forth, and in perfect time the paddles were dipped and the canoe shot on her way.

“All Ukula go Vaileli, to-night,” Tuamana said, after the launch had again been headed for the harbor. “Big ‘Talola’ and ‘Siva’ to Missi Klinger.”

“Fine business!” O’Neil exclaimed. “They’ll come back in the morning to find a new king at Kulinuu.”

“Kataafa go too,” the chief added.

Phil could hardly suppress his joy. Things were certainly coming their way.

As Phil ascended the ladder of the “Sitka,” Commander Tazewell anxiously awaited him. But before the commander could ask a question, Phil hurriedly but guardedly outlined the news, and followed his captain into his cabin.

“Schultz has deserted us,” the captain told him. “He got ashore during the night—probably let himself down over the side into a waiting canoe. So you can speak out.” Phil had been conversing in guarded tones.

The entire situation from beginning to end was discussed, the executive officer and most of the important officers of the cruiser being present.

“The ‘Sacramento’ will be here at ten o’clock,” Commander Tazewell said after all points had been discussed. “Captain Sturdy and his British sailors will hold all roads leading into Ukula west of the Mulivaii River while we garrison Matautu to that river. A squad will take care of the pilot station, and guards must be furnished all the consulates in Matautu.”

All listened eagerly. The time all had looked forward to was fast approaching.

“Lieutenant Morrison will command our men,” the captain added, as he rose to his feet in sign of dismissal. “We may of course have opposition, but we must guard against precipitating the fighting. Our duty is only to hold and not to advance. When the admiral arrives he will of course tell us what to do next.

“Tents, rations and supplies will be landed to-night after the sailors are ashore,” he added.

Phil remained behind after the officers had filed out of the cabin, having been detained by a word from his captain.

“I want you to take the news to Mr. Lee at once,” Commander Tazewell said to the lad, “and show him the necessity for secrecy. No one must know until we are ashore.”

Phil made himself presentable, and then was conveyed to the shore by the captain’s boat, which on its return carried a letter from Commander Tazewell, addressed to Commander Sturdy of the British war-ship, acquainting him of the change in the situation and the plan for the night.

Mr. Lee and Judge Lindsay were both jubilant over the turn of affairs, while Alice fairly danced with joy. Miss Lee, quiet and dignified, rather shrank from the thought of possible bloodshed. There was only one drop of bitterness in Alice’s joy. Phil insisted that Avao should not be told until after the “Sacramento” had entered the harbor, and landed her men. He feared the fatal custom of women’s gossip among the Kapuans.

“I sincerely hope this strong stand of our admiral will have the required effect, and that we shall have no further bloodshed,” Mr. Lee said solemnly.

“There can be no lasting peace in Kapua, Lee,” the judge exclaimed earnestly, “so long as the islands are administered by three rapacious beasts and animals of prey. A lion and two eagles can never act in harmony. It is best for the people that only one should govern. Herzovinia has the greatest interests on this island; she should govern it. Our presence is but a stick in the molasses.”

“I agree with you in principle, judge,” Mr. Lee replied, “but even you are not willing to see one nation, in deliberate disregard of the treaty rights of others, seize what is not hers.”

“That, my dear sir, is not a matter of politics, but of morals,” the judge answered. “Let us decide the justice of the situation; but after that is determined then I am anxious to see this triple government at an end.”

When Phil left the consulate the two officials were yet deep in their discussion. As he hurried toward the landing he noted that the town was almost deserted of the usual crowd that gathered along the main thoroughfare at this time of the early evening. The “Talola” at Vaileli was going to be popular.

As Phil’s boat rounded to alongside of the gangway, the “Talofa” had just anchored within a few cables’ length of the “Sitka.”

Preparations were being carried forward with great expedition on board both the American and British war-ships, but everything was being done so quietly that no suspicion had so far been aroused on board the other cruiser anchored only a short distance away from each of the allies.

As the ship’s bell sounded two strokes (nine o’clock) a long line of boats filled with armed sailors shoved off from the two ships and were towed by steam launches swiftly toward the shore. Phil and Sydney accompanied Commander Tazewell in their towing steam launch. The “Talofa” had been turned over to a squad of sailormen under a petty officer, to prevent the native crew from attempting to take her out of the harbor.

Phil’s eyes were upon the dark outlines of the Herzovinian war-ship as they passed close alongside of her. There was a grim smile of satisfaction in Commander Tazewell’s face as he heard loud voices raised in the guttural Herzovinian tongue, apparently the officer of the watch berating the men on lookout for their slackness. Then came a hurrying of footsteps upon the deck and finally a hail in broken English.

“Is there trouble on shore?” the voice called hesitatingly.

Commander Tazewell waited several seconds before replying.

Once more the voice was raised, this time more loudly. He had apparently just discovered a second line of boats on the other side of his ship, ladened deeply in the water with sailormen.

“Has there been a fight on shore? Why are you landing your men?”

“Just a precautionary measure,” Commander Tazewell’s clear-cut voice answered. “Is your captain on board?”

“No, sir,” came back the answer. “He has gone to Vaileli.”

“It’s no matter,” Commander Tazewell replied. “When he returns I will explain everything to him.”

“Thank you, sir,” said the voice, but it was plainly noted that the speaker was greatly perplexed.

“Only a young officer left on board,” Commander Tazewell said quietly to the midshipmen, “and taken off his guard, he doesn’t know what to do.”

“What could he do?” Phil asked excitedly.

Commander Tazewell shook his head doubtfully. “He might land his men too, but that could not defeat our purpose. With the English and American sailors in military control of Ukula, it would take a stronger man than Count Rosen to annex the islands.”

The boats glided alongside the wharf at the foot of the Siumu road and the sailors, their accouterments rattling musically, scrambled upon the dock and quickly formed their companies. But few commands were given. Each officer knew his station already.

The English commander, fairly beaming with joy, joined Commander Tazewell on the dock.

“I say, that admiral of yours is a jolly good sport, and we’re behind him with every man and gun,” he exclaimed effusively, “and we’re not much beforehand, either,” he added. “The natives all say that the Vaileli ‘Talola’ was arranged by Count Rosen in order to inform Kataafa and his warriors that the islands will be annexed as soon as their war-ship, hourly expected, arrives. It’s a sort of informal annexation, don’t you know. And they’ll come back and then, as you Americans say, they’ll ‘wake up.’”

Commander Tazewell joined in the laugh. The dock was clear. All the men landed had gone to their stations, and their boats had been towed back to their ships to be filled with tentage and provisions.

“By now,” he said grimly, “there probably are many eager messengers hurrying to acquaint those at Vaileli of what is happening on the beach of Ukula.”

Phil was suddenly aware of Avao’s presence at his elbow.

“Kataafa’s men all take guns,” she whispered guardedly. “Mary Hamilton, she go too to Vaileli. What are sailors going to do?” she asked excitedly.

“You’ll see to-morrow, Avao,” Phil replied evasively.

“Too few men,” Avao persisted anxiously. “Kataafa many thousand.”

“What does she say?” Commander Tazewell asked, suddenly noting the eagerness in the girl’s manner.

Avao repeated what she had told Phil.

“We’ll have about three hundred more inside a half hour, Avao,” Commander Tazewell assured her. “Don’t you think we can stand off an attack with those?”

“Fa’a moli-moli,”[39] she said humbly; “but, Alii, I know my people, and I afraid bad men may tell them fight. Suppose I go to the count and say do not permit armed natives to come to-night back to Ukula. If they come maybe have big fight.”

“There seems to be something in what the girl says, Tazewell,” Commander Sturdy exclaimed. “Of course our plan is to refuse them entrance, and open fire if they persist. Yet we’d like to prevent a fight if we can win without it.”

Commander Tazewell remained silently thoughtful for several minutes. To him the plan savored too much of asking the count a favor. However, it was in the cause of humanity. If word was to be sent the girl could not take it alone. An officer from his command must go. He turned his eyes toward the midshipmen, standing silently awaiting the decision.

“Perry, will you go to the count at Vaileli plantation?” he said quietly. “Explain the situation and see if he will agree to prevent bloodshed. To-morrow we can treat with him. Monroe,” he added hurriedly, “please take my gig and tell the executive officer of the ‘Sitka’ about using the search-lights beginning at fifteen minutes of ten.”

Sydney saluted, gulped down his disappointment and turned toward the waiting boat. He had been on the point of asking to go with Phil.

“You and Avao can get mounts at the consulate,” Commander Tazewell continued, turning to Phil, who stood like a sprinter ready to run or a hunting dog about to be unleashed.