CHAPTER XXII

WAR IN EARNEST

WHEN Phil and O’Neil reached the beach, the “Sitka’s” shells were screeching angrily over their heads and exploding in the bush behind them. The sailors had been collected and formed on the beach road to repel an attack. Three officers and eight sailors were missing and a score had received wounds. The command of the force fell to a sub-lieutenant from the English cruiser. Tupper, Morrison and Patterson had been killed and left upon the field.

“There were at least a thousand of them,” Sydney exclaimed as he met Phil and grasped his hand silently, thankful for his escape, “and Scott or some white man was with them. Many of the men say they distinctly heard a white man’s voice encouraging the natives to charge us.”

The sailors were apathetic, stunned. The suddenness of the attack and their defeat had unnerved every man of them.

“If we could only have used the machine gun,” Childers moaned plaintively, “we’d have had a different story to tell.”

Little by little the men’s shattered nerves were mended. The “Sitka’s” shells yet screeched overhead, but the rebel natives had retired.

The commanding officer gave the order and put the force in motion. It was a sadly disheartened band that entered the town of Ukula an hour later.

When the doleful news reached the American admiral, he was beside himself with anger at the white men whom he firmly believed had instigated and made possible the ambush. Far from yielding, all effort was now ordered to be concentrated upon swift punishment to the rebels.

Lieutenant Gant came ashore from the British ship to command all the loyal native troops. Several hundred loyal warriors were now added, having been brought from Kulila. One thousand strong they were mustered, and all were armed with the latest patterns of the Lee Metford rifle from the British and American war-ships. The white troops, unused to bush fighting, by the admiral’s order were hereafter only to garrison the town, while offensive work was to be done exclusively by the loyal native troops. A plentiful supply of white sailors was sprinkled among the native companies, to teach them how to use their weapons and how to take cover.

Through the women the fate of the fallen officers and sailors was learned. All had been beheaded; but Kataafa when he learned of this savage act had ordered the bodies and heads to be buried and their graves marked.

Phil and Sydney were given commands in the native regiment, and O’Neil went with them.

All day and every day they drilled their men. Meanwhile the rebels were drawing their lines closer about Ukula.

The Herzovinian consul had, immediately after the unfortunate fight with the rebels, gone in person to offer his sympathy to the admiral for the sad loss of life. Admiral Spotts received him in stony silence. He listened to his words but vouchsafed no answer, nor even thanked him for his sympathy.

“Against his countrymen, whom he should control,” the admiral exclaimed to Commanders Tazewell and Sturdy, after the discomfited consul had departed, “the blood of every man killed in these islands should righteously cry out vengeance.”

Phil, who had been present, repeated the admiral’s words to O’Neil. The sailorman nodded his head in silence for several minutes.

“What were you going to say?” Phil asked quickly. He had seen a look in O’Neil’s eyes, and knew that the sailor was looking at the sad episode from a different standpoint.

“Well, sir,” O’Neil replied apologetically, “I am not saying the admiral isn’t dead right. That count and Klinger have sure brought on this war and are responsible for the men killed. But, sir,” he added, “I was here when twenty Herzovinian sailors were killed and their heads taken by this same Kataafa. They were killed by bullets furnished by Americans and Englishmen. They blamed us then—we blame them now.

“Don’t you see, sir,” he added earnestly, “the Herzovinians think we are now ‘quits.’ They lost twenty sailors; we have lost eleven, including three officers.”

“Now,” Sydney said thoughtfully, “is the time for the white men to get together and stop this useless war.”

Phil and O’Neil gazed at him in surprise.

“When we have lost our first battle,” Phil exclaimed scornfully. “Why, Syd, that is contrary to human nature. The Herzovinians might be willing to compromise, but we cannot accept a truce until we have proved that our courage has not been affected. When we have driven Kataafa away from Ukula, then we might be willing to treat for an armistice, but never before.”

“I agree with the humanitarian view of Mr. Monroe,” a voice from behind them said solemnly. The lads turned to find Judge Lindsay beside them, smiling in fatherly fashion upon them. “Now is the moment of moments to bring together the warring factions. To do so,” he added, “we must sacrifice some of our selfish pride. But we would thus spare innocent human lives.

“Have you heard that Klinger has been arrested, and is now held in jail by our naval forces for the crime of instigating the rebels to attack our sailors?” he asked. The judge spoke without sign of feeling.

“I cannot see,” he said after a pause, “what evidence they have against him. He supplied guns to natives to fight natives. That they used their weapons against the white men I am sure was not his wish.”

“Begging your worship’s pardon,” O’Neil said respectfully, “Klinger was here ten years ago, and saw twenty of his countrymen killed through the work of white men of our race. Do you believe, sir, he has forgotten that? Klinger has no fear. When we stood and talked with him at Vaileli before the fight, I thought I saw a look in his face, like one who believes something for which he has long wished was about to happen. He didn’t owe us anything, and the line of talk we gave him didn’t make him feel any the more kindly toward us. I am dead sure now that he knew that Kataafa’s warriors were between us and Ukula, waiting to attack us, but the memory of the monument in Kulinuu for the martyred Herzovinian sailors kept his mouth shut tight. No, sir, he let us go to our defeat almost with joy in his heart, and somehow,” O’Neil added solemnly, almost reverentially, “when I remember that terrible day, just before the hurricane that wrecked us all, I haven’t it in my heart to blame him.”

“So you were here then,” the judge exclaimed in surprise and interest. “Well, I wish I could be the instrument to bring together the two sides, and bring peace to these beautiful islands; but I suppose the blood of our poor fellows cries out for atonement, and we must fight on.”

Lieutenant Gant with his native regiment was almost ready to take the offensive.

“We’ve got to be mighty keen about it,” he exclaimed to some of his officers. “A cable is on the way to New Zealand by the mail ship that left to-day. The Powers will soon put a stop to this show when they learn the results of our first battle.”

But before Gant could take the field to retrieve the defeat, Kataafa became suddenly bold and advanced his lines within a couple of hundred yards of the allies. They moved during the night, and strange as it may seem women did not bring the news beforehand.

Matautu was the point of attack, and the foreign resident section was swept by bullets.

The natives taunted each other from their earth intrenchments, firing wildly, but neither side made an attempt to leave the protection of their forts and attack.

Across the Fuisa River on the east of Matautu the Kataafa and Panu warriors faced each other, and here Lieutenant Gant had despatched several native companies of reënforcements to hold the road leading into Ukula.

The sailors, by order of the admiral, had been held in reserve. They were only to be used in case Kataafa undertook to rush the earthwork defenses. They held the second line of defense.

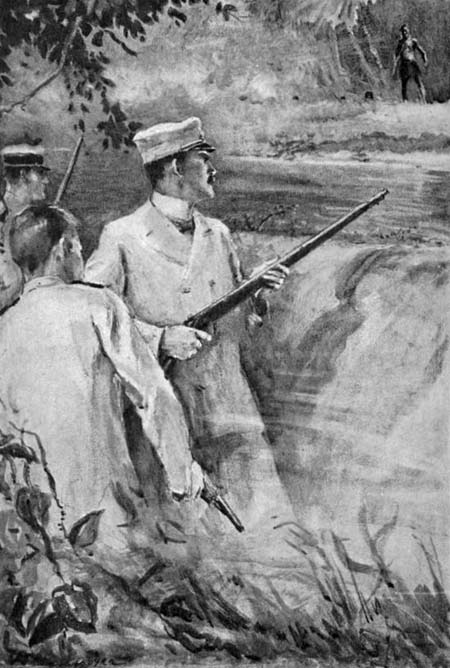

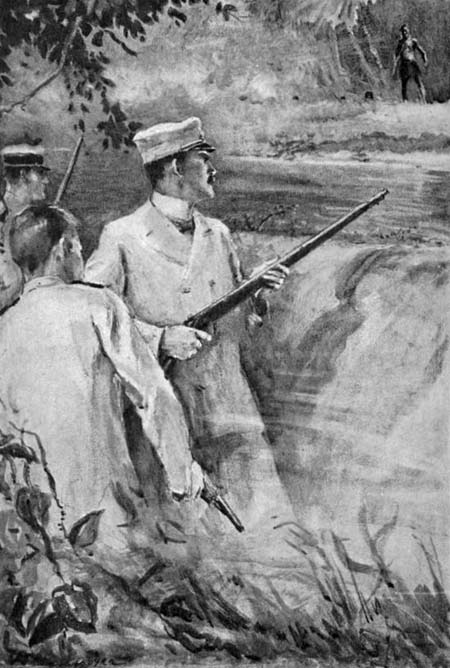

“It’s a perfect shame,” O’Neil exclaimed disgustedly, “to see these fellows throw away their ammunition. Why, a squad of sailors could have picked off twenty of those blackened faced natives across there in the last ten minutes.” He picked up the rifle that had been idly lying beside him in the trench and adjusted the sight to two hundred yards. “Watch me lay out the next fellow who gets funny and jumps on top of his fort and shakes his fist at us.”

HE DID NOT FIRE

The midshipmen watched him interestedly, for O’Neil was a dead shot.

Suddenly a fine looking warrior leaped upon the trench, brandishing his gun and head knife, using the forceful but picturesque Kapuan tongue in boasts and taunts, hurling them upon all those of his enemies across the river.

O’Neil calmly raised his gun, but he did not fire. He dropped it into the hollow of his arm.

“It’s too much like murder,” he said, and both midshipmen breathed a sigh of relief.

“This isn’t war,” Phil complained bitterly. “We are fighting children. I’d as soon shoot a schoolboy showing himself in bravado from the top of his snow fort as to shoot at those joyful warriors. To them fighting is fun. They do not realize that they are uselessly destroying human life.”

“Look!” Sydney exclaimed in admiration, as a Kataafa warrior was seen to rush into the river a few hundred yards above them and endeavor to reach the body of a native whom he had slain. A rain of bullets fell all around him, and as he reached the side of his victim, his head axe raised, he fell dead. So excited had both sides become that no thought of personal safety was given. Both sides stood upon the top of their trenches and uttered their savage cries of defiance. The Kataafa men who had cheered on their hero, exulting in the prospect of a trophy, saw themselves suddenly exposed to a disgrace.

“We ought to stop it,” Sydney exclaimed. “Look at our men exposing themselves needlessly.”

“You might as well try damming Niagara first,” Phil returned. “It would be an easier job.”

“There’s the real thing for you,” O’Neil cried, bringing his rifle up to his shoulder as a lithe Kataafa native darted across the intervening water scarcely half waist deep, swung the dead body of his friend upon his back and returned to his trenches unscathed.

“If they don’t stop this foolishness,” the sailor said, “I’m going to teach ’em a lesson.” He lowered his rifle from his shoulder. “I could have dropped him a half a dozen times,” he complained, “and yet these wild savages have wasted a barrel of lead shooting at him, and not a single hit.”

The excitement along the Fuisa River began to die down after this last piece of bravado. O’Neil and the midshipmen had sent word to the chiefs in their vicinity to save their ammunition.

About three o’clock those at the Fuisa River were much concerned over heavy musketry fire behind them and on the right flank of the allied position. A woman came along the road from Ukula, carrying fruit for her relatives in the trenches.

O’Neil spoke to her, inquiring the cause of the firing. She answered quite calmly and passed on down the trench.

“She says she heard Kataafa would attack along the Siumu road, and supposed that was the cause of the firing,” O’Neil explained. “There goes the artillery,” he exclaimed, as all distinctly heard the crash from the village in their rear where some English howitzers were mounted. “They must have driven the natives back. Look out!” he cried suddenly.

There was no need for further warning. The midshipmen, glancing up over the top of the trench, saw the Kataafa warriors were beyond their trench and advancing toward the river, firing, gesticulating, taunting, dancing and singing. A hail of bullets met them from the Panu side; but nothing seemed able to stop the movement.

The contending factions were about equal in numbers. The Kataafa men having willingly abandoned their trench to fight in the open, their enemy, not to be outdone in chivalry, bravely mounted on top of their own earthworks and awaited the attack. Meanwhile both sides fired blindly. Neither side took time to aim. Even with such poor fire direction, however, many men on both sides were being hit.

O’Neil and the two midshipmen had gotten suddenly over their hesitancy in shooting down a native enemy, and their example was being followed by about fifty white men, after endeavoring in vain to keep their natives under cover.

“Pick out the leaders,” O’Neil exclaimed. “I got that fellow. I am sorry! he was such a fine looker.” Again he fired, and each time his exclamations told the result of his shot.

Phil and Sydney realized that it was not a matter of choice. That rush had to be stopped, even if the entire force against them was wiped out, and they loaded and fired eagerly, but carefully, every shot bringing down an enemy.

“They’ve had enough!” Sydney cried joyously. Those near had turned and were fleeing back across the stream. Once the panic had seized them, the entire Kataafa force was fleeing for cover.

“Now after them,” O’Neil suggested to the midshipmen, and this same thought had apparently come to every white sailor along the loyal line. An English sub-lieutenant some hundred yards above had begun the sortie, and presently the whole line was in the river advancing rapidly after their fleeing foe.

Breathless, Phil found himself in the enemy’s trenches. The natives had dashed on into the bush to pursue their broken foe.

The trench made by Kataafa was quickly razed and again the loyal warriors were quietly, yet joyously, back in their own forts.

It was not until this lull in the fighting that the midshipmen realized the extent of the attack upon the center of the allies’ position along the Siumu road. The firing seemed closer and in greater volume. The howitzers had been reënforced by Gatlings and pom-poms, or one-pounder automatic cannon, from the English ship.

“I say, that looks as if the big attack were down there,” the sub-lieutenant exclaimed anxiously. He had come down to talk with the midshipmen. “Suppose you take your company and see if they need help. After that rush I think we have more than plenty to keep them off here.”

Phil, Sydney and O’Neil led forth about one hundred excited natives on a run through Matautu. In front of the legations two companies of American sailors, forming the reserve for the flank which the midshipmen had just left, hurriedly joined on behind.

Ahead, in front of the Tivoli Hotel, the artillery could be seen firing down the Siumu road. The air was full of flying bullets, apparently coming from all directions. The entire stretch of road from the American consulate was bullet swept. Phil saw that it was deserted, but he could not stop to take cover. It was evident that on the Siumu road the biggest attack was being made. As the natives and sailors approached Phil saw several companies of white men advancing from the other direction. He soon recognized the English from Kulinuu, coming to reënforce the center.

Lieutenant Gant, mounted upon a pony, in all that hail of bullets came galloping toward the midshipmen.

“Go straight down the road,” he ordered. Phil marveled at his calmness. “They’ve driven our natives back almost into the town. The guns are shelling behind them. It’s only making noise. We can’t shoot into them for fear of hitting our own.”

The extra three hundred arriving turned the tide of battle. The Panu natives, encouraged by their white officers and sailors from the war-ships, now turned and charged their enemy. The impetus of the reënforcements carried them through the front ranks of the enemy and into the middle of the horde. Out in the jungle the natives spread out, and each line was quickly reënforced by squads of sailors.

By four o’clock the attack had been repulsed, and the loyal natives and their allies were again withdrawn into their forts. All the Kataafa forts taken had been destroyed.

Many heads were brought into the town, but these were ordered buried, and the natives, after some grumbling, finally complied.

Phil and Sydney saw the heads collected by native chiefs appointed by Lieutenant Gant. One head in the gruesome pile gave him a start that he will always remember. It was that once proudly carried by Captain “Bully” Scott. The grayish whiskers and long matted locks of once black hair, but now turning gray. The usually sun-brown face had turned to an ashen pallor. Yet the likeness in death was as vivid as in life.

Phil had the head taken up and wrapped in tapa cloth, and then carried it to Commander Tazewell.

In front of the Tivoli Hotel they found him.

Phil quickly explained his mission.

All retired inside the hotel while a box was ordered brought.

Phil laid his ghastly relic on the floor and gingerly unwrapped it.

All gazed upon it in silence. Commander Tazewell nodded, and Phil rewrapped the head carefully and placed it within the box.

As they left the hotel O’Neil brought up the native who claimed to have taken the head.

“He says he didn’t kill him,” O’Neil said, “but I think probably he did, and is afraid to say so. He thinks we are displeased because it was a white man.”

“Who did it? Ask him,” Phil ordered.

“He says a white man shot him. He saw it, and when the white man didn’t take the head, he did,” O’Neil replied, after a short conversation.

The native so closely questioned by these white officers was becoming very much concerned. His eyes rolled from side to side seeking apparently somebody to take his part. Finally he leaped away and grabbing a man by the arm dragged him excitedly toward his inquisitors.

It was Stump.

“He kill! He kill!” the native cried out pointing his finger at the surprised white man.