CHAPTER II

DISCORD AMONG THE WHITES

THE day after the ceremony of welcome to Kataafa, Phil and Sydney again accompanied their captain on shore. Commander Tazewell took a lively interest in everything that was going on and was delighted to have such enthusiastic young supporters.

“You’ll find,” he said after they had landed and sent the boat away, “that the natives of both factions are equally friendly to us. That is a good sign and I hope it will continue.”

The highroad of Ukula was filled with half-naked muscular men and lithe, graceful, dark-eyed women. Every native exhaled the acrid odor of cocoanut oil. The men’s long hair was plastered white with lime and tied on top in the form of a topknot.

“The lime bleaches the hair red, you know,” Commander Tazewell explained, noting the lads’ curiosity at this peculiar custom. “The oil is to prevent them from catching cold. They go into the water, you see, any hour of the day, and when they come out they are as dry as ducks.”

The officers had landed at Kulinuu, the traditional residence of the Malea-Toa family, from which many kings had been chosen and to which Panu-Mafili belonged. On every hand they encountered good-natured smiling natives. “Talofa, Alii”[3] was on every lip.

“Ten thousand of these fellows are encamped in the vicinity of Ukula waiting to see who the chief justice makes their king,” the commander said. “You see,” he added, “strange as it may seem to us, two chiefs may rightfully be elected. Election depends upon quality of votes rather than upon quantity. So according to traditional Kapuan custom when two kings are elected, they decide it by having a big battle. That is the normal way, but we have persuaded the natives that arbitration is more civilized. Now the chief justice decides and the three nations support that decision.”

“It looks rather as though Herzovinia would support the judge only in case he decides for Kataafa,” Sydney said questioningly. “If that country refuses to back up the judge what will happen?”

Commander Tazewell was thoughtful for half a minute.

“According to the treaty all are required to agree,” he answered. “There is no choice. Once the decision is made that creates a king, all who oppose him are rebels. That is the law, and these foreign war-ships are here to uphold Judge Lindsay’s decision, right or wrong.”

As the three pedestrians, dressed in their white duck uniforms, white helmets protecting their heads from the tropical sun, reached the hard coral road leading along the shore of the bay, the panorama of the harbor opened and delighted the eyes of the young men.

The white coral reef, lying beneath scarcely half a fathom of water, was peopled by natives gathering shell-fish to feed the greater influx of population. On the bosom of the dark green water, beyond the inner reef, and almost encircled by spurs of a second ledge of coral, lay anchored the war-ships of three great nations. In the foreground, lying on their sides, two twisted red-stained hulls, the bleaching bones of once proud men-of-war, told of the sport of giant waves that had hurled them a hundred yards along the inner reef and drowned many of their crews. This manifestation of the power of a tropical hurricane, that might come almost unheralded out of the watery waste, prevented any relaxation of vigilance. At all times the war-ships were kept ready to seek safety at sea, clear of the treacherous coral reefs. To be caught at anchor in the harbor of Ukula when a hurricane broke could mean only another red-stained wreck upon the reef.

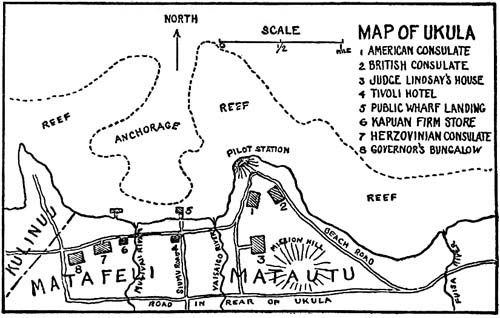

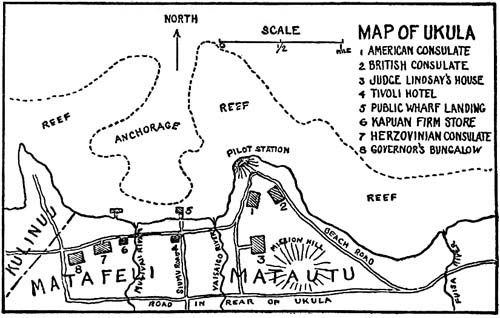

MAP OF UKULA

The road soon left the water’s edge. Now it ran several hundred yards inland through groves of cocoanut, banana and breadfruit trees. Fringing the road were many spider-like, grass-thatched native houses, similar to those they had seen among the groves at Kulinuu. Seated on mats under these shelters were numerous natives, and the Americans as they progressed received frequent cordial invitation to stop and refresh themselves from the very hospitable islanders. Commander Tazewell, during his stay in Kapua, had acquired some facility in the language, which greatly delighted the childlike natives, and they lost no opportunity to engage him to join their meetings, in order that they might listen to their own language from the lips of a “papalangi”[4] chief. But apparently the commander did not intend to stop. Both midshipmen now eyed longingly the cool interior of a large and pretentious house which they were approaching. From the entrance a stately warrior beckoned them to come and partake of the milk of a cocoanut.

Commander Tazewell waved a solemn acknowledgment. “That’s Tuamana, the chief of Ukula,” he said to his companions. “We’ll stop for just a minute. It was he,” the commander added as they approached the delighted chief, “who saved so many lives during the hurricane when those two war-ships were thrown up bodily on the reef, and several others were wrecked at their moorings.”

Tuamana grasped each by the hand in turn and then led them to mats laid upon the pebbly floor. He clapped his hands, and almost at once from behind the dividing curtain of “Tapa”[5] cloth, two native girls glided, gracefully and with outstretched hands, to the side of the “papalangis.” Seating themselves the girls began industriously fanning the heated officers. Phil soon appreciated the reason for this delicate attention; swarms of flies hovered about them, to fight which alone would soon exhaust one’s patience.

Commander Tazewell and Chief Tuamana engaged in quiet conversation in Kapuan while the chief’s talking man, a native educated at one of the mission schools, came frequently to their aid when the commander’s limited native vocabulary gave evidence of being inadequate.

Phil and Sydney were thus left free to enjoy the novelty of their surroundings.

The two young girls fanned and giggled in turns until Phil, unused to such delicate attention from the opposite sex, insisted upon taking the cleverly wrought banana leaf fan, and much to the amusement of the two girls began fanning himself and the girl too. After a few moments this young lady arose, bowed and disappeared behind the screen convulsed with laughter.

“You’ve offended her,” insisted Sydney. “Haven’t you learned yet to give women their own way?”

But Phil’s gallantry was to receive its reward. A third graceful Kapuan girl, her high caste face beaming upon them, glided through the tapa screen. Bowing low before Commander Tazewell, she took the vacant place at Phil’s side.

Commander Tazewell made a jesting remark in Kapuan, which caused every one to laugh except the two midshipmen.

“This is Tuamana’s daughter Avao,” the commander said. “I told her she’d have a difficult time making a choice between my two handsome aides; but I see she has made up her mind already.”

Avao had taken the fan from Phil’s hand and was now efficiently fanning him.

A half hour later as they were standing, bidding good-bye to their hosts, Commander Tazewell announced to Phil that the chief’s daughter had paid him a signal honor.

“She wants you to be her felinge,”[6] he said, his grave eyes sparkling. “It’s a Tapau’s[7] privilege to choose. Your obligation is to present her with soap, tooth powder, in fact, anything she fancies that you can get in the ship’s store. For this you are privileged to drink as many cocoanuts and eat as much fruit as you desire at her father’s house. She will even send you presents of fruit, tapa and fans. If I were Mr. Monroe, I’d envy you your luck, for Avao is the belle of Ukula.”

Avao blushed under her bronze and playfully struck the commander with her fan.

“Leonga Alii!”[8] she exclaimed abashed.

“She understands and speaks English as well as I do,” he said, laughing at the girl’s sudden shyness. “Once I thought she’d make me her felinge, but I suppose youth takes rank.”

Once more on the road Commander Tazewell became again serious.

“That affair yesterday is taking on a darker aspect,” he confided. “Tuamana says that every one knows among the natives that if Judge Lindsay decides for Panu-Mafili then Kataafa has been persuaded by the Herzovinians to make war.

“Tuamana, of course,” he added, “is a loyal man. He is on Panu’s side, but will be loyal to whom Judge Lindsay decides is really the king.”

In front of the big wooden store in the Matafeli district of the town, Commander Tazewell stopped. Many natives were gathered there. The porch was crowded, while within the store there seemed to be only standing room.

“What mischief is going on here?” he exclaimed, a perplexed frown on his face.

Suddenly Klinger and the stranger of yesterday darkened the doorway. The stranger gazed coldly upon the Americans but gave no sign of recognition. He and Klinger continued to talk in their guttural Herzovinian tongues.

Phil suddenly observed that the air of friendliness they had noted earlier was now lacking. The natives no longer greeted them. Instead in the native eye was a sheepish, sullen look.

“That was Count Rosen,” Commander Tazewell said as they again moved onward. “Klinger, of course, is active and sides with Kataafa. Klinger’s wife is a native, you know, a close relative of the high chief. I suppose he’d like to have royalty in the family.”

“The store looked like a recruiting station,” Phil suggested.

Commander Tazewell nodded gravely. “It may be,” he replied.

The Matautu section of Ukula, set aside for the official residences of the consuls of England and the United States, was being approached.

At the gate of the American consulate, Mr. Lee hailed them. The consul was naturally a peace loving man, and the fact that he had with him in Kapua his two daughters was an added argument for peace.

“Come in, commander,” he called from his doorway.

They turned in through the gateway.

“All manner of war rumors,” Mr. Lee exclaimed, as he shook hands, “are going the rounds. The latest is that a paper has been found written by Herzovinian statesmen some years ago declaring their country would never, never permit Kataafa to be king. The Kapuans believe that this will make Judge Lindsay decide for Panu-Mafili. Until that disgraceful affair of yesterday, and the rumor of this paper, we all thought that whatever the decision the three consuls would unite to prevent war. Panu-Mafili has said openly he and his followers would abide by the decision. Kataafa appeared willing, but has as yet made no statement.

“The situation is alarming, commander,” Mr. Lee added gravely, “and I for one am at a loss what should be done.”

“Arrest the white men who are inciting Kataafa to revolt in the event of an adverse decision and ship them from Kapua; that’s my remedy,” Commander Tazewell answered promptly.

“Count Rosen and Klinger,” the consul exclaimed. “Impossible!”

Commander Tazewell shrugged his shoulders.

“It’s the one way to prevent war,” he said.

“The Herzovinian consul, after agreeing to stand with us and prevent a war, has now assumed a mysterious air of importance and we can get nothing definite from him,” Mr. Lee complained bitterly. “If my advice had only been followed and Kataafa kept away until after a new king had been crowned, this perplexing state could not have existed.”

Commander Tazewell was thoughtful for several minutes.

“Mr. Lee,” he said gravely, “I believe that bringing Kataafa back at this time was a Herzovinian plan. The chief has been in exile for five years and in a Herzovinian colony, and I hear was treated as a prince instead of a prisoner. Although his warriors killed Herzovinian sailors in the last revolt, now he favors that nation. Once he is king of Kapua he will advance all Herzovinian interests. They may hope even for annexation, a dream long cherished by Klinger and his countrymen.

“Yes, if the judge decides against Kataafa there will be war,” he concluded solemnly.

Phil and Sydney listened eagerly. Though these native affairs were not easy to understand, yet they could not interrupt and ask for explanations.

At this time there came an interruption in the serious talk between Commander Tazewell and Mr. Lee. It was the arrival of the two young ladies. They had been out in the “bush,” as the country back of the sea beach is called in Kapua. They appeared, their young faces glowing with health from their recent exercise and their arms full of the scarlet “pandanus” blossoms.

Margaret, the older girl, was a woman in spite of her nineteen years. She greeted the newcomers to Kapua with a grace that won the midshipmen at once. Alice, two years her junior, caught the boyish fancy of the lads instantly. She seemed to carry with her the free air of the woods, and exhaled its freshness. She had scarcely a trace of the reserve in manner of her older sister. Her greeting was spontaneously frank and unabashed.

While Margaret presided at the tea table, around which Commander Tazewell and the consul gathered, Alice impressed the willing midshipmen into her service, and with their arms loaded with the pandanus flowers, led them to the dining-room. Here she placed the brilliant blossoms into numerous vases, giving to the room with its paucity of furniture a gala aspect.

“Do you care for tea?” she said questioningly, implying clearly a negative answer, which both lads were quick to catch.

“Never take it,” Phil replied quickly. “Do you, Syd?”

Sydney smiled and shook his head.

“Because if you don’t, while the others are drinking it, we can climb Mission Hill back of the town and enjoy the view of the harbor. It’s not far,” she added glancing at the spotless white uniform of the young officers.

She led them at a rapid pace across the garden and by a narrow path into a thickly wooded copse. The path was apparently one not frequently used and was choked with creepers and underbrushes. After a score of yards the path led at a steep angle up the wooded side of one of the low surrounding hills, which at Matautu descended almost to the harbor’s edge. Here the shore is rocky and dangerous.

Alice climbed with the ease of a wood sprite, while the midshipmen lumbered after her in their endeavor to keep pace.

“Here we are,” she cried joyfully as she sprang up the last few feet of incline and seated herself in the fork of a small mulberry tree.

Out of breath, their white trousers and white canvas shoes stained with the juice of entangling vines, and with perspiration streaming in little rivulets down their crimson faces, the two young men looked with amazement at their slim pace-maker; she was not even out of breath.

“Isn’t it worth coming for?” she exclaimed, perfect enjoyment in her girlish voice. “See, the town and the harbor and all the ships lie at our feet; and everything looks so very near;” then she added whimsically, “I sometimes pretend I am queen and order everything and every one about—no one else ever comes here,” she explained quickly. “My sister Margaret came once, but never came again.”

“It’s not easy to get here,” Sydney said, panting slightly, “but it would more than be worth the trouble if by coming one could really know the feeling of being a king or a queen. I haven’t sufficient imagination. What should you do if you were queen?” he asked of Alice.

She drew her brows down thoughtfully.

“I don’t know all that I should do,” she replied earnestly, “but the very first thing would be to send away every papalangi.”

“The war-ships too?” Phil inquired. “I call that hospitable!”

“I might keep you,” indicating both lads by a wave of her free hand, “as leaders for my army, but every one else would be sent away and leave these children of nature free to live their lives as God intended they should.” A deep conviction in the girl’s voice was not lost upon the midshipmen.

“Suppose you tell us of Kapua,” Phil said gently, after a short silence.

“Yes, do,” Sydney urged eagerly.

“Tell you of Kapua Uma,”[9] Alice said wistfully. “I have lived here now three years, and I feel as if the people were my people. They are gentle, generous and lovable, except when they are excited by the papalangi. The white men have brought only trouble and sorrow to the islands. No Kapuan has ever broken his word, except when the white men have betrayed him. In all their wars they have been generous to their foes. They never harm women and children. The white men incite war, but are free from injury, except when they attack the Kapuans first.

“Once all the rich land near the sea belonged to Kapua. Now white men have stolen it away by fraud and deceit.” Alice’s eyes flashed indignantly, while her hearers were thrilled by the fervor in her young voice. “The foreign firm of which Klinger is manager, called the ‘Kapuan Firm,’ owned by Herzovinian capital, is no ordinary company of South Sea traders,” she added. “It is the feet of the Herzovinian Empire, holding the door of annexation open. The firm’s business grows greater every year. They import black labor from the Solomon Islands and hold them to work as slaves. The treaty gives the Kapuans the right to choose their king, but the firm will sanction no king who will not first agree to further the interests of the Kapuan firm.

“Kataafa once fought against the firm and won, but he was exiled by the Herzovinian government. Now a majority of people again wish him for king, and this time the firm is not only willing but anxious that he should be made king. England and America represented in Kapua see in this a bid for annexation. Judge Lindsay will soon decide between Kataafa and Panu-Mafili. Panu has given his word he will not fight. Kataafa signed a sworn agreement in order to obtain the consent of the three Powers to his return from exile, that he would never again take up arms.”

Alice stopped breathless. “There you have the full history of Kapua in a nutshell,” she added laughingly as she slipped down from her seat.

“Poor Panu-Mafili is only a boy. His father, you know, was the late king Malea-Toa or ‘Laupepe,’ a ‘sheet of paper,’ as the natives called him, because he was intellectual. Panu begged to be allowed to go away and study,” she said, “but our great governments need him as a big piece in the political chess game.”

“More aptly a pawn,” Phil corrected.

Alice was gazing wistfully seaward.

“Out there,” she said after a moment’s silence, “is a sail. It’s probably the ‘Talofa,’ a schooner from the Fiji. The natives say ‘Bully’ Scott and the ‘Talofa’ scent out wars in the South Seas and arrive just in time to sell a shipload of rifles.”

The midshipmen saw the tops of a “sail” far out on the horizon.

“If Kataafa needs guns to defy the chief justice, there they are,” she added.

“Isn’t it against the law to sell guns to the natives?” Sydney asked.

Alice regarded him with high disdain.

“‘Bully’ Scott knows no law nor nationality,” she replied. “To give your nationality in Kapua is a disadvantage, because then your consul interferes with your business. When you’re trading in ‘blacks’ and guns, it’s best to deprive yourself of the luxury of a country. ‘Bully’ Scott is from the world.”

“How do you know that is the ‘Talofa’?” Phil asked incredulously, but all the same greatly interested.

“I don’t know,” she answered gayly as she led the way toward home; “but the ‘Talofa’ is a schooner, and the natives believe she will come. And that’s a schooner.”

Her logic was not convincing to the midshipmen, but then they had not lived three years in Kapua. Schooners were not frequent visitors at Ukula.