A Yawoo Life.

By Geoffrey Clarke

Chapter 1

Parents and Parties

‘’Yawoo, yawoo, wallahwallah wigwam! Tie him to the tree’’, screamed the mud plastered ten year old Red Indian Knollabugs who had captured me, this seven year old whiteman Mellabug from the other end of the rural town. As they fired slender privet hedge arrows into my shins, I cried copiously. The breath stopped in my lungs as I realised that there were not always Mum and Dad around to save and protect.I shook with fear and trepidation waiting for the fatal arrow shot. The wooded coppice where the attack occurred was dark and overgrown. The nearby Catholic church quiet in its unresponsive vastnessand yet distant appeal as a refuge to which to run.

‘Why are they attacking me? Maybe it’s myleather school satchel with its dried up sandwiches, or perhaps they are just bandits?’ I George, son of a local schoolteacher, wonder if it was a class privilege concern.

The gang of Yawoos stop for a short change of arrows which gives me the chance to breathe and think.

‘What are they going to do next? Are they going to hurt me more? So far it’s only my legs, but maybe they’ll aim higher to my head and chest.’

I’m only dressed in my wartime issue khaki shorts with no underpants, grey flannel shirt with no socks, and just open sandals. This is the result of nineteen-forties’ deprivation and the fag end of rationing. It gives me the chance to question why the son of a poor teacher and jaded housewife mother could be chosen for bullying. The school house was pristine, curtains in my bedroom would’ve been a luxury, and the post war standard of living very low – so why me?

There were some regional rivalries, sectarian or boundary based that caused their animosity. I knew that the town was already divided in terms of linguistic difference, Welsh versus English, and that there were before the deluge mods who hated chavs like me. Or could it have been their juvenile energies flowing with adrenaline and nowhere to go?

‘You little jerk. You couldn’t join our gang, you scruffy Mellabug. We’re Knollabugs. We rule!’

Then after a few more moments,

‘Shall we let him go, the ragged Mellabug from the wrong end of town?’

They fired a few more desultory shots, laughing out loud. Anyway, they turned and fired their last arrows, releasing me with some final whoops of pre-pubescent joy from the bully boy gang. Cut and bruised and cursing them under my breath, I limp home, legs running with blood, my face streaming tears. On reporting the incident to my Mum, Dot, she tells me to go and fight my own battles!

Leonard Jones was one of the cussed little devils who were shooting the arrows into my legs. He was the one whose family had one of the new fangled cat's whiskers wireless sets. They were rented, and the refreshed batteries were delivered by van weekly to keep them going, provided the rent was paid. Two shillings and sixpence a week, I think. Later, when grown up, he became a successful musician in a rock band touring Wales and beyond. He was a close mate of mine, but he always seemed to be distant as if he regarded me as an inferior type of person who couldn’t match his spirit of adventure, fun and fancy freedoms. Of course, we were both dressed in the almost warn out shoes and clothes of the period due to the rationing and shortages. Our favourite tipple was dandelion and burdock that came in returnable bottles full of fizz and pop. It was like an early form of Coca Cola and tasted a bit like American root beer. Spanish root was another of our favourites. We could buy a stick of it for a farthing (one quarter of a penny) and suck it until it dried up into a shrivelled yellow twig, as we went our way to our single sex, segregated schoolroom. Some of the kids in my class in 1944 were without shoes; and it was always amusing that John Davies who lived in a dilapidated terraced house next door to the school was always late while we Yawoos coming down from Hillside were on time for class.

I bumped into Leonard again at a dance for young bloods when I was a young man in my twenties, and we shared our memories of gangs and pirates, Yawoos, and sand pit builders at an age when we could have been married men. It was perplexing to see someone who you had played with as a child with whom one had shared so many childish adventures and who was now a competitor for the eligible young ladies in our peer group.

Arthur Moody, the one who did the yawoo wallah wigwam Indian battle cry was a doctor's son from Windsor Road. Arthur was one of the boys who passed the scholarship exam and went on to be a prominent surgeon like his Dad. It was ironic that I used to play in his sand pit with him and other local children getting ourselves and especially our shoes into a mess, such that his mother would chide us for bringing sand into the drawing room with its grand piano and music stool. But the cucumber sandwiches and iced teas were a bonus that George particularly relished when he was feeling deprived of food. Dot always encouraged me to play at Moody’s house, as if the cachet of association with a doctor’s family was one that she relished.

Shortly after the arrows incident, returning from segregated, single sex Junior School, I saunter home taking the route through the woods rather than through Windsor Road, past the slaughter house, the Co-operative grocery store and up Coronation Street. Reaching the Knoll pond, it appeared to have been drained, so I decide in a moment of madness to cut straight across it rather than go around and pass the changing rooms for the swimming pool section. As I run through the muddy recesses of the pond, I begin to sink further and further into the mud. Reaching my upper calves, I start to panic.

‘Shall I turn back? No. Keep going, it’s not far to the other bank’.

By now I am waistdeep in the mud, and wonder if I will be sucked down into a whirlpool of quicksand never to be found again or live to tell the tale. By some miracle I reach the other side and, covered in mud and sludge, hurry on to the schoolhouse for comfort.

My Dad,Perry, is fortunately at home when I run into the back kitchen and with his usual calm and practised hands stands me in the sink, washes me down saying,

‘Never mind. You’ll be alright in a while’.

And he kept me warm at the kitchen fire supplying me with the strong bottled coffee that he loved so much and that smelled so fine. Although I was glad he didn’t mistake the gravy browning in the similar dark brown, unlabelled bottle for it this time. The kitchen where he welcomed me was next to the outdoor privy where newspaper served for tissues, and was always scented with the smoke from the indoor stove burning away on the local anthracite coal. Clean yet efficient, the kitchen was the hearth of a healthy, happy home that could endure such misadventures. The coal was cheap and plentiful, and you could always be sure of a warming at its cracked, browning, celluloid covered portholes that seemed to ooze a kind of bronze coloured melted gum from the fire resistant material.

Three generationsin this story live, love, exist and ride rough shod over time. Set in a number of countries, humorous emotions abound, scenes and backdrops take us from Glamorgan to Tehran, from Monmouthshire to Paris and Warsaw and from home base in Metropolitan cities to deserts in the Middle East. Each of us lives in a desert which contains a small human being; physically aware of his diminutive stature, tiny, microscopic, and minute.

May Hanbury, is born in a small, grey, back to back, terraced cottage in Glamorgan, which as some may know is not the best of starts in life for a family bound on a saga to cover three generations. It ends, or at least halts temporarily, in endless wealth and freedom. And May is the smart cookie in this tale.It was as cottages go, homely and clean, warm and secure, with a steep row of steps leading up from a village dominated by the pit to a dark brown door, lovingly painted by her father. He cannot enter the story, since he had so little to contribute to May’s rich life pattern.She was much maligned by her arrogant, erstwhile father, John, who had no opinions, no thoughts, no guts, and no fame.

Whilst May was young she loved the hills of Monmouthshire. Especially the heather and the bilberry capped mountain tops, where she was once lost in a sudden mist so fierce that she feared she would never find home again. It started as thin, grisly stuff; but soon developed into pea-soup variety fog through steamy, cloudy mist to blanketing, all-embracing fog of the variety of smog so well-known to London in the fifties.

She eventually found her way down from the mountain-top by adhering to tiny rivulets of streaming springs which she knewwould lead down inexorably through the marshy, boggy area at the top, through the brooks at the back of her terraced cottage, to the river at the base of the basin where she resided.

May, however, showed from an early age a keen sense of intelligence, learning the hard way about life’s flint hard messages. She culled from valleys and brooks, clouds and streams, and seemed to absorb her wisdom by a keen intelligence and a ready humour. I remember the way I bounded up those steps to be met by a dark, huge, yet kindly Alsatian named Rex. He had met his end when, blind, he’d rushed down the same flight of steps into the path of a heavy goods wagon laden with industrial materials, long since rendered unnecessary by the path of progress, like Rex.

May had that reverend, careful, sweet nature of a working girl, but what distinguished her from others was her voice : it gratinated - until those around her froze. Why her tone could have been so off putting to a small boy may have been its originality and unusualness, coupled with an accent so back guttural that it could have cut through steel. But her sweetness conquered all. Her generosity of emotion triumphed and her hearty companionability won all over. She was of the middle stature, towards blousiness really, for at seventeen she had had dough to rub, flour to sieve and pastry to roll as well as the next girl. Yet when it came to family life, May exhibited those qualities that made her so loved and respected by close family and friends, like Perry and Dot.

The cottage was a two up, two down miner’s cottage with an outside lavatory and no inside running water. The miners would have to crack the ice on the outside tap before washing themselves in the morning before the early shift down at the pit. The front room was kept meticulous for visits from the vicar and the like. That was where the best furniture, linen and Swansea china,usually a flower patterned bowl and jug, and some delightful figurines in a glass cabinet, carefully stood on display for the attention of any admirers who cared to see them. The doorstep was highly scrubbed and kept clean by the housewife on a regular basis There was the same, charming, endless air of sentiment in the raw there. On the landing there stood a melodious musical box that played the Jangling tunes that were contained in its rolls. I don’t wish to imply that the boot blackened Dutch oven or the delightful, tuneful, acidulous tones of the mechanical musical box were what contributed to it. However, the heat of emotion was apparent to a small child of six, as I was then. Mixed irrevocably with the smell of cabbage cooking on the roaring coal stove (incidentally, a tonne of anthracite coal was delivered free to miners) and the pungent aroma of the floor polish. When the miners came home from their early morning shift by four o’clock, covered in grime and coal dust and stinking of sweat and toil, they would take a bath. Only the whites of their eyes were untouched by the coal dust and their clothes and body were totally covered with the results of eight hours underground hewing at the side of the coal face. The wife would wash the man’s back in a tin bath normally hung up outside the kitchen door. In front of a raging fire, he would flannel off the grime and muck of his stinking occupation.

Returning to May, the young nurse, who was her contemporary, had that stout hippiness of the British nurse. She was built like a brick chicken house, really as a result of all the standing, I suppose, and she could go like a stuffed rabbit when it came to it. Dot herself, unfortunately, was at the worst end of a serious accident which occurred when, leaving her cycle parked at the top of a steep terraced street, she returned, after rain, to carry on to her next Queen’s Nurses call. Finding the brakes inoperative, she careered on downhill until she dashed herself and her bike into the wall of the skin specialist’s at the junction of Pantyfelyn Hill.

This event put paid to her career as a nurse for over a year and during this period she met Perry, the middle aged physiotherapist who had to tend daily to her rehabilitation. Dot had actually preferred another man she had met shortly before the accident, named Ted, but his lack of concern during her enforced idleness at Gwent General Hospitalled to the realisation of his inadequacy. Perry, however, the dogged, faithful type, met Dot out of hospital hours and soon cemented a regular relationship.

‘Would you like to go to the pictures at Cardiff on Friday evening?’ he asks commiseratingly.

‘Yes, I’d love that.’

‘Can Ted come too?’

‘Of course’, replies Perry, and off they go to the first local showing of Al Johnson’s ‘The Jazz Singer’ the movie with a sound track, not just pictures.

Ted had no real interest for Dot since the bike crash.

‘Sorry I couldn’t come to see you’ confessed Ted, lugubriously.

‘That’s no matter, I was well looked after.’

And so the relationship with Perry developed. He had to be prompted to ask her out to a café the following week, and had to be encouraged all the way along the line.

‘Perry, why don’t we go to Bindles on Barry Island on Sunday?’

‘Alright, I could get some time off from the hospital on a Sunday afternoon, I suppose.’

‘Well, we could always go for a walk along the beach...’

‘No, that’s alright. Dancing will be fine.’

The tea dances at Bindles were the highlight of the social calendar. They did the ‘Black Bottom’ with puritanical reserve and followed up with ‘Saratoga Rag’ to the restrained airs of Syd Sylvester and his ballroom orchestra. No one could say that the young generation of working couples in that part of the world were either abandoned or exotic.

‘Having fun?’ Dot enquires.

‘Yes, thanks…’ he adds, with no real enthusiasm.

‘Let’s leave early and take that walk along the beach.’

So they walk outside into the cool evening air and slip onto the esplanade for a romantic, moonlit stroll.

‘It’s a lovely evening.’

‘Yes, I’m sure you are enjoying it.’

But Dot had longings for a more florid and tempestuous affair.However, Perry was stolidly loyal and needed no prompting to suggest a further excursion the following week.

‘Let’s take the train up to Mountain Ash station and walk on the mountain’, he suggests.

‘That would be ravishing’, gushes Dot, not seeing the pun, and bites back her desires for concerts, operas and cinemas.

The walk turns out to be pleasant, relaxing and without incident. It isn’t very long before the conversation turns to the subject of a more permanent future. But it has to be remembered that the times were not easy and, even for a man over thirty-five, with alittle capital, it would be tough to find a place to live and have enough money to make a secure home.

The years that follow remain long -lasting months of hard saving and long suffering economies in order to obtain the deposit on a house. Perry worked evenings as a prison service physio to earn extra money and Dot went back to her nursing. The announcement of the engagement, after seven years of steady, regular courtship in the old manner, went into the local paper. The marriage takes place in a tinny church near Cardiff on the eve of the second world war.

Perry, his age against him, gets turned down for military service and spends the war years as an ARP and school physiotherapist. The marriage turns out to be happy and uneventful and a child is born to the couple in the early months of the war at a makeshift hospital in barrack buildings at Bridge Road.

My earliest (repressed) memory is reported to be that I walk up Cimla Hill on foot at the age of fifteen months to reach the school house at the top when the family moves from Ponty to Cimla. I suppose my first real memories must be of sitting up in a pram in the garden of that suburban home and of long hours spent in the snow and wind despite all weathers. Mother was a fanatic for the current child- rearing theories of fresh air, sun and sleep.

A steel table had been delivered to the oddly red painted front room of the school house for protection from bombs that were potentially to fall from German aircraft on their way to a blitzkrieg on the nearby docks of Port Margam. That was me, during one of the frequent power outages, diving under the table screaming and moaning:

‘Mummy, Mummy. Are the Germans coming?’

‘Finish your homework by the candlelight’ was my Mum’s cool response.

Sometime later, Perry took me aged twenty months up to the fields overlooking the schoolhouse and pointed west towards the red flame filled skies above the port that had been repeatedly bombed over three nights by the German Luftwaffe.

‘Look. Look, son, Swansea’s burning!’

Swansea was bombed for three consecutive nights. Only London and Swansea suffered bombing on three nights in a row. The centre of the city around the Plaza cinema were mounds of rubble and debris. They were bulldozed away making an impassable barrier into Henrietta Street from the Kingsway down to St Helen’s Road. Even in the ‘fifties the bomb site hadn’t been cleared and it was an appalling reminder of the horrors of war. Why the Germans decided to bomb Swansea is not sure, but one of the intentions of the enemy was to demoralise the population. According to Geoff Brooks, the sirens went off at 7.32 p.m.

on Wednesday, 19 February 1941. The populace were only expecting a night raid, but it continued for over three hours on each of the nights with eighty planes involved. Fifty-six thousand incendiary bombs were unleashed onto the city. One thousand two hundred high explosives were sent crashing to the ground by the bomb aimers. The destruction around the port was less than that in the city centre, as if the bombs actually missed their target. Weaver’s Flour Mill on the dockside was their target site – a huge monolith structure made from reinforced concrete. There were parachute flares and fire bombs. The whole place was lit up and visible from our home eight miles away.

The rationing of food during the Second World War meant we were kept on a pretty tight shopping budget with four ounces of fat, four ounces of meat and a corresponding limit on items like cheese and butter. But the schoolhouse has an ample garden and the family gather red currants, raspberries, gooseberries, peas, beans and the like. My sister, Jane Marie, would scuttle along the rows eating fruit and veg as she went along. Blackberries were the highlight, and we would scour the fields, when they were in season, picking copious amounts of the luscious fruits that Mum would convert into jams, stews, pies and tarts.

She would roll out her pastry on a wooden board with awooden rolling pin. Ever frugal, she would chop off the ends of the pastry on the pie dish and keep it for later. She would never tell me when she knew the baking was ready. But I supposed it was by her sense of smell in that hot kitchen atmosphere. One of her secrets was to put a broken, Chinese patterned cup under the top layer of pastry to stop it from sinking. She’d add a topping of milk to the pastry, to prevent it from burning in those last vital minutes, when she was assessing the readiness of the cooking. These tarts and pies were the delight of Perry, who had the disconcerting habit of spitting out those tiny, pesky blackberry seeds that had become lodged in his teeth.

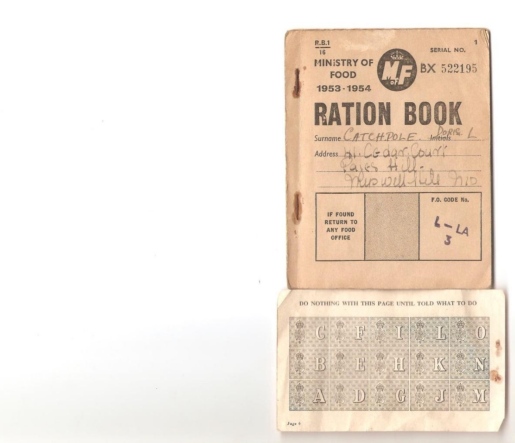

Figure 1 My Aunty Doris's ration book.

It’s funny how the proclivity to accidents seems to run in families. Looking out of the sitting room window, suddenly I see Jane Marie hurtling down the slope outside the schoolhouse on her three wheeled contraption, a trike. She Is out of control. She’s screaming blue murder, and I rush out the front door to see if I can help.

‘What happened, Jane?’

‘I don’t know’ she says, tears streaming down her face, blood pouring from her knee. ‘It isn’t my fault. The brakes don’t work’.

Like mother, like daughter.

Anyway, Mum’s a nurse and she cleans her up with the usual warm water with a measured, economical dose of Dettol.

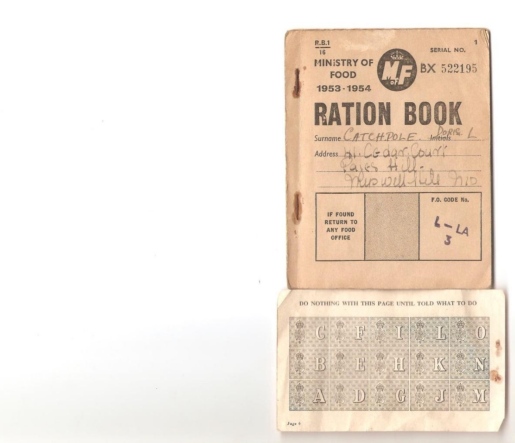

Figure 2 Note the allowances used up for each portion.

My father, Perry was a saintly chap. He never argued, but somehow always got his own way. He subtly managed Dot by a superior intellect, wisdom and native cunning. For example, he liked strong tea, so on pouring out it would be:

‘You first, Dot, have your cup of tea before me.’

And he would thereby end up with the stronger one. But if Perry wanted something he would get it by patient waiting and dogged determination to be the one to prevail, but Dot didn’t seem to notice that he always ended up winning. His self composure was remarkable perhaps due to his earlier background in mining electrics where safety and self command underground were paramount. He was what you might call a man with not a hair out of place, and who commanded respect by his modesty, good humour and constant pleasantness.

‘Do you believe we may see the end of the war soon’ he puts to Dot, naively.

‘Well, depends who bombs whom the most, I suppose.’

‘Don't think it will last beyond 1940’, he says.

Nipper was fighting of course, at least in the Educational Corps as agym instructor. Nipper, Perry’s cousin, agile, wiry and handsome with muscles to match appeared to be the equivalent of a modern - day American wrestler - the charisma much the same. He and Perry could and would vault over any five-bar gate with ease; hop, step and jumping, then placing the whole forearm on the top bar and vaulting up and over like a ballet dancer.

Come 1945, and me now nearing six years, I experience the first major traumatic event in my life. I can clearly recall at the end of the war reading (for I could read newspaper headlines at the age of four), that Japan had surrendered after the horrors of the mushroom cloud. The paper boy had tossed the newspaper into the front garden that afternoon, and I vividly see in my mind's eye a picture of a large, bulbous balloon of smoke and dust, the relevance of which I really didn't quite understand.

The press-picture of the Hiroshima mushroom cloud that signalled the end of WW II was an appalling and inexplicable image for a young child's mind to comprehend. It was a cataclysmic event that put an end to the second world war, but the loss of life, health concerns and appalling radiation problems persist to this day in Japan. However, I ran up the grass bank to a front door lovingly polished by Dot. Nearby bushes of wisteria and fuchsia seemed as magical as anything I had yet seen in my early life. Apart from a small accident with a radio which followed a long loving bath attended by mother, there was little to worry about.

‘The gurgles in the bathroom wall

Are heard, but never seen at all

Who put the water in the taps?

The most industrious, little chaps’

she would recite, and regale me with tales of Bluebeard and his seven wives, and how he murdered his first wife. Was there any subtext there, I wonder?

I come downstairs wrapped in towels. I open the door. The flex of the wireless is loosely strewn across the corner of the room. I run across to listen to another exciting episode of ‘Dick Barton: Special Agent’. I trip over and break the radio. A piece of Bakelite is lying on the floor. It smelled strangely chemical and cloying. Dun darun darun durun went the theme tune of Dick Barton always at 6.45 p. m. after which it was bedtime. Exciting episodes with Jock Anderson and Snowy White as his mates and companions. There were a total of 711 episodes with maximum audiences of 15 million. Its end was marked by a leading article in ’The Times’. It excited me for adventure, travel, and stories of derring-do, which might account for some of my more nefarious activities to be recounted in this book. The radio play recounted the adventures of ex-commando captain Richard Barton MC who, solved all kinds of crimes, escaped from dangerous spots and saved the UK from disaster time and time over.

Commenting on the broken Bakelite cover of the valve operated wireless, ‘Never mind’ coos Dot, but Perry turns a little edgy and raises his voice manfully at me,who, as delicate as a soap bubble from his bath, cries miserably. As a physical specimen Perry was outstanding, handsome and Russian looking, probably the result of ancestors like Count Leo Tolstoy, Warren Buffet and Alexander Hamilton, the founding father of the USA, according to our DNA. He was very hairy and olive skinned. His hair Bryllcreamed, sleeked back and centre- parted. He had a nobility and bearing that people took to be foreign, yet he was steeped in English forebears like Lippiatt his mother, Gould, his grandfather, and his grandmother née Bartlett; proud stock emanating from Wiltshire and Somerset. Yet, period photos of the time do seem to mark him out as having a swarthy foreign complexion. His accent was pure Rhondda, for he would pronounce ‘whole’ as ‘whool’ and reservoir as ‘reservoy’. It was always accentuated on the final syllable like the ‘p’ in trip.

‘Drat it, Perry. Can't you organise the electrical stuff in this house’ barks Dot.

‘Doh’, for that's what he called her in tighter moments,

‘For the sake of peace, I shall’.

Surely enough Perry carefully, methodically changes the electrical wiring with his horny hands exacting a penalty from contact with electrical tape and shorn cable. When he pushes it down the edges of the carpet, it buries itself.

‘Perry. I know it’s late, but let's for God's sake do something about this lighting’, she nags on.

Dot was shorter than her other cousins, one of whom, Marjorie, is still alive as I write in 2015 at the age of 94. She was busty and well proportioned, bossy and highly efficient as a housewife, district nurse, and later Matron of a large care home. She possessed violet coloured eyes and brown tawny hair and sheer white skin, altogether different from Perry. Always maintaining pretensions, even though we were as poor as church mice, Dot had an elegance and an unparalleled dress sense. Her favourite maxim was Blue and green should never be seen Except upon a Fairy Queen.

When dawn broke on this quarrel, I find myself ready for action. But the war is a long, red – skied image, not a reality.

There were street parties to mark VE (Victory in Europe) Day. My speciality was the eating of the marzipan layer of the cakes that other kids didn’t like. I could get down about five helpings without being sick. We sat in rows out in the street faced with jelly, custard, cakes and lots of ‘pop’- fizzy drinks that we got in returnable glass bottles that rewarded you tuppence (about 5p.) when you took them back. We were recyclists, too.

On one street party day, probably for VJ (Victory in Japan) Day, it came on to rain and Mum spiritedly invited everyone back to the schoolhouse. There were people in the bedrooms, in the kitchen, and the sitting roo