A Zloor For Your Trouble

I was sitting on the cot in the little room at the rear of my hangarage, where I keep my equipment and most of my trophies, and cleaning my .257 Roberts when the knock came at the door. It was a sharp, decisive knock. Then the door opened and I saw Westley Marks for the first time. It didn't excite me.

He said, "Mr. Napoleon Prescott?"

I began to say, "Everybody calls me Nap," but then I didn't. There was something about this guy that didn't click with me. Say what you will against snap judgments, I still take my love at first sight and enmity often the same way.

For one thing, he gave me the impression of looking for trouble; he was about six foot two and he had what he obviously thought was an aristocratic face. His nose was the type that used to be called Roman—and looked like it'd be a honey to punch. He was dressed like a million, which didn't particularly impress me either. I'm on the rugged side myself, red headed and homely to boot.

He took in the rifle I was cleaning, and his eyebrows went up questioningly. "Collector?" he asked. Somehow or other he managed to put over the impression that he thought I didn't have the intellect to have a hobby.

"Not exactly," I told him. "This is a tool, not a collector's item."

There was almost a laugh in his voice now. "You mean you use that relic in your work?"

I put the gun down, told myself to take it easy, then said, "They've made a lot of developments in weapons since this rifle was popular, but it still has advantages on certain types of jobs. For instance, if I was after a Kodiac bear, up in the Alaska National Park—"

He snorted, "I'd take a Bazook-rifle and be sure who came out on top."

"Sure you would," I told him, "and there wouldn't be enough bear left to feed your dogs. I usually work for a zoo or a museum; they either want the animal alive, or in good mounting condition. I admit that they've got guns now that one man can carry that'd sink one of the old time battleships; okay, but in my line I seldom need one."

He didn't like my tone of voice, but he dropped the point and began looking around for a place to sit.

I hadn't asked him to sit down, and I didn't now.

I said, "Was there something I could do for you?"

"I wanted to hire you for a rather lengthy period," he told me.

"I'm all booked up for the next six months."

"This is something rather special."

"It always is when somebody wants you to cancel a job with a regular client."

He didn't like me any better than I liked him, that was obvious. He said, "This comes under the heading of work for the government."

I told him, "There are other professional hunters. Some of them nearly as good as I am." The last was sarcastic.

"Possibly better," he said, "but none of them are your size."

I could feel my face approaching the color of my hair at that one. "Keep my size out of it," I snapped. I indicated with a thumb a little statuette on my desk. "The guy my mother named me after was pint size too. He got along all right."

He looked over at Bonaparte. "Ummm," he said. "Napoleon was a big name once—but he's only a bust now."

"Listen," I told him, "you're asking for a bust yourself. Why don't you run along? I'm busy."

He ignored me, found a chair that had nothing but a few magazines on it, tossed them to the floor and sat down. "Your name was brought up because you're the smallest professional hunter on Earth. It'd save a few thousand credits in getting you to Mars and back."

That stopped me. "What in kert are you talking about?" I growled.

"The government wants a specimen, at least one, of a zloor."

"A what?"

"A zloor," he repeated. "A small Martian animal."

I scowled at him. "And just why does the government want a zloor?"

"That's a secret."

"Okay. I'll tell you another secret. Somebody else can catch the government a zloor. I've never been off Earth and I haven't any particular hankering to go now." I picked up the .257 Roberts again and reached for my oil can.

He got to his feet, something just this side of a sneer on his face, and said, "I doubt if you could have got one anyway."

I said easily, "If anyone else could catch it, I could."

He reached for the doorknob, "I'd lay a thousand credits against that," he said. He began to leave.

"Wait a minute, buddy," I snapped. "Are you just sounding off or have you got a thousand credits you don't care what happens to?"

He turned and faced me. "I am willing to wager a thousand credits that you can't capture a zloor."

"How big are they?"

"About the size of a rabbit."

I glowered at him. "They very fast, or very poisonous, or what?"

He shrugged. "They can't run quite as fast as a common Terran hare, and I understand they're quite gentle."

"Then why haven't they been captured?"

"Among other things, Napoleon," he rolled my name over his tongue as though he got a big laugh from it, "there have been only a few hundred persons in all that have gone to Mars. Few of them, to my knowledge, have been interested in the life forms there. The expense of freight in space is much too high for Terran zoos to transport Martian life forms—particularly alive—considering the cost of duplicating in the space craft the living conditions necessary to—"

"All right," I snapped, "just a minute." I picked up the viso-phone and dialed rapidly. In seconds, Jerry Mason's friendly pan lit up the screen.

"Listen, Jerry," I said, "Have you ever heard of a Martian zloor?"

His eyebrows went up. "Sure, what—"

"Are they particularly fast?"

"No, of course not. But—"

"Are they dangerous?"

He grinned, but he was still puzzled. "I'd say they were about the least dangerous animal I ever heard of. But, Nap—"

"Just one more question, Jerry, I'm in a hurry. Do you think I could catch one?"

"I can't think of anything you could catch easier." He started to give one of his short bursts of laughter. "But—"

"Thanks, Jerry," I told him. "See you later." I snapped off the set and turned back to Westley Marks.

"All right, answer just one question and I'll take up that bet of yours. What's secret about this?"

"If I tell you, you'll take on the job?"

"The job, and the thousand credit bet," I grated.

"Very well. It is suspected that the zloor is an alien life form."

I stared at him. "Are you around the corner?" I demanded. "Of course it's an alien life form. Didn't you just say it's a Martian animal?"

"Ummmm. But some authorities think it is alien to this solar system. At least they suspect so—that's why the government wants a specimen to dissect and thoroughly investigate. They haven't the facilities on Mars, of course, so it will be necessary to bring one back here."

I still stared at him. "Alien to the solar system? Your roof must be leaking. How would it get here?" A sudden suspicion hit me. "You mean it's intelligent? I thought there wasn't any intelligent life forms on Mars."

He shook his head. "It's a stupid herbivorous animal." He shot a glance down at his watch. "The shuttle for the space station leaves in three hours. Can you make it?"

I glared at him. "You give me plenty of time, don't you?—I'll make it all right. But first I want this bet down in writing."

"Of course," he said smoothly.

I had to hustle plenty. The zloor wasn't any bigger than a rabbit, and I knew that life forms on Mars were in general small, so I took nothing larger than my little carbine size .22 Hornet, another gun that Westley Marks probably would have sneered at but which I wouldn't have traded for all the automatics you could shake a stick at.

I didn't take much else; no clothes except the shorts I wore when I climbed into the shuttle rocket for the space station. When Marks said freight rates in space were high he just wasn't whistling, Terra Forever. I could buy clothes and any other equipment I needed a good deal cheaper on Mars than the cost of transporting them there would come to.

For one thing, when anybody left the colony planet to come back to Terra, they invariably left behind everything in the way of clothing and personal equipment; for another, a certain amount of these things were being manufactured on Mars from native raw materials in an attempt to escape the murderous space rates.

After the four G's acceleration had cut off and we were in free fall, I took the opportunity to read the contract I'd hurriedly signed with Westley Marks. On thorough reading, the contract didn't seem too bad. All my expenses to and from Mars were paid by Marks. I also got five credits a month in the way of salary—no fortune, but average pay for a Terran worker. If I caught a zloor and brought it back alive, I got a five hundred credit bonus; if I brought two back alive, a seven hundred credit bonus. If I brought a dead one back, I got a three hundred bonus. Westley Marks didn't seem to be interested in getting more than one dead one since there wasn't any provision for a larger number.

He'd given me to understand that this job was for the government, but from the way the contract read I was working for the Marks Enterprises. That irritated me for a minute or so, but I finally shrugged it off. He probably had a government contract to secure one of the things. I still couldn't figure out what his angle was—but I knew there must be one; too much money was involved to make this a routine assignment such as I usually work on for the zoos. Evidently Marks ran some sort of an expediting outfit which took on off-trail contracts.

At this point I might do a little in the way of describing my trip to the space station which circles Terra and is used as a take-off point to Luna and the planets. I might go on and tell of my journey from there to the space station in orbit about Mars, and then, further still, of my shuttling down to Fort Mars and my first impressions of landing there, of the one-sixth gravity, the thin air, the plastic dome which covers the whole little city. But the trouble is that a hundred people a lot quicker with a dicto-typer than I am have already done the job. I'll just leave that part of it and take up with my first contact with my fellow Terrans on Mars.

One of the old gags is to the effect that when Greek meets Greek they start a restaurant. Okay, maybe, but I do know this, that when man in general starts up a new colony one of the first buildings he puts up is a bar.

At any rate, as soon as I was settled at the Biltless Hotel—the name, of course, is a gag, but the place lived up to it—I made my way to Sam's.

Now, there's something that invariably happens to people who get around. It's happened to you, if you're one of us. Maybe you're walking through the Congo Game Preserve, figuring there isn't another man, white or otherwise, within a hundred kilometers. Suddenly you run into another party and somebody yells, "Hello Nap! What in kert are you doing here?" The last time you saw him was in San Francisco. Or maybe you're doing some solitary drinking in some obscure bar in Guatemala. The guy next to you looks over and says, "Say, aren't you Nap Prescott, the brother of—" and, of course, you are.

Well, that was it. I hadn't any more got up to the bar and told Sam, "Let me have some of this Martian woji I've been hearing so much about," when I heard somebody yelp, "It's Nap! I'll be a grinning makron if it isn't Nap!"

I turned around and there was Mike Holiday, as big as life and twice as drunk.

He waddled his bulk over to me—Mike always waddles when he's soused—from the table where he'd been sitting.

"By the Holy Jumping Wodo," he crowed, "I'll bet my left arm you came to get a zloor."

I'd been grinning and holding out my hand to clasp his, but that stiffened me.

He saw it and began to laugh uproariously. "Another joiner of the club!" he yelped. "Come on over and meet your fellow members. You got one of them Westley contracts too?"

That did it.

I went over and met the boys. Mike Holiday wasn't the only acquaintance of mine in Fort Mars. In fact, it was like a convention of the outstanding professional hunters of Earth.

They all shouted their greetings, some of them laughing so hard tears rolled down their cheeks. Evidently they got a big kick every time a newcomer was added to their ranks. I shook hands with some, but most were too hilarious to go through the ceremony.

Blackie Conover yelled, "I'll bet anybody two to one he brought a .22 Hornet to shoot himself a zloor. Two to one!"

"Do we look like suckers?" Mike yelled back at him.

I sank into a chair and took it for awhile. "I can wait," I growled at them. "Sooner or later somebody'll get around to telling me what goes on."

"He can wait, he says," Doughbelly fairly yelped in delight. "Brother, he ain't just a whistlin' Terra Forever, he can wait! Bring on the woji! Start the initiation!"

I woke up in the morning in Mike Holiday's apartment. I groaned and told myself that I was sworn off of woji for all time.—I didn't know then that Terra-side liquor sold for ten credits a bottle.

Mike was grinning down at me. "You'll get used to woji," he said.

"I should live so long," I moaned. Then I sat up suddenly in the bed. "You guys wouldn't tell me anything last night," I said. He was still grinning. "That's part of the initiation into the Zloor Club. What'd'ya want to know, Nap?"

I swung my feet over the side of the bed and came to a sitting position. I groaned and shook my head in an attempt to clear it.

"What are half the professional hunters I know doing on Mars?"

He spun a chair around so that the back faced me, and straddled it, his arms resting on the top rung. "Same thing you are, Nap. Being suckers for that makron Westley Marks."

I started to say something there but he interrupted me with a wave of a hand. "This is what it boils down to. Marks has a contract with some branch of the government to bring back one or more zloors. And don't ask me why he doesn't go out and catch one himself—he's tried."

"He has, eh?"

"Yeah, he has. Had a whole crew up here. What makes it nice for him is that he's on a cost plus basis. If he never succeeds, it'll still be money in his pocket; if he does, he gets a whopping big bonus. Every time he sends another man up here to take a crack at getting a zloor, he makes money. No doubt the way he told you the story, you'd think you were the only one trying."

I snorted, "He told me I'd been picked because I was the smallest pro hunter in the game."

Mike Holiday grinned. "He picked me because I was so big.—I could stand the rigors of life on Mars, he said."

"Well, if it's a racket, why doesn't everybody go home on the next ship?"

"Probably for the same reason you won't. That sharper made me so sore I bet him five hundred credits I could catch a zloor."

"I bet him a thousand," I groaned.

Mike whistled. "Where'd you ever get a thousand credits, Nap?"

"I broke into my piggy bank," I growled. "It's every cent I had in the world."

"Well, we're all in the same boat. He made bets with all the boys. If we go back, we lose. As long as we stay here we make five credits a month, plus expenses.—And, besides, all of us are just conceited enough to think we can figure out eventually how to get one of the things home."

"Now we're getting to the point," I told him. "What's so hard about catching a zloor?"

He began to grin again. "Nothing," he said. "And that's all I'll tell you now. Go out and find the gruesome details yourself."

I went over to the wash basin and filled the bowl and dipped my head into the water. I didn't say anything else to him until I'd dried myself and climbed into my clothes.

"All right," I said then. "Where do I go to see about getting equipment and men for an expedition to the zloor country?"

He laughed. "All you need in the way of equipment is your feet, that is, besides a plastic oxygen mask when you leave the dome." He pointed out the window. "Just head for the nearest rocky area, there's lots of it; you won't have any trouble finding a zloor. In fact, they're numerous—no natural enemies."

I scowled at him. "What keeps them down then?"

"Insufficient forage, I guess. You'll see."

I picked up my .22 Hornet rifle and started for the door. "No time like the present to—" I began to say.

Mike was still grinning in the irritating manner he'd been displaying ever since the night before. "You won't need that gun," he told me.

"I'll just take it along anyway," I snapped.

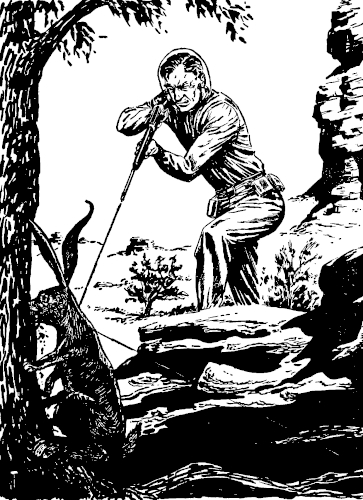

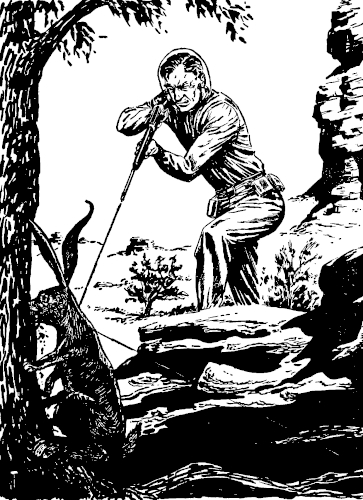

After leaving the dome through one of the airlocks, I headed out onto the surface of Mars, weighted down with my leaded boots, standard equipment for cutting down some of the effect of the one-sixth gravity of the planet.

Over to the westward, possibly three miles away, seemed to be a barren, rocky area. I knew that Mike Holiday wouldn't have deliberately lied to me, that was where zloors were to be found. I made my way in that direction.

"About the size of a rabbit," I muttered. "And half the hunters on earth can't bring one back."

I made the rocky area and found myself a suitable prominence from which to look around. In less than fifteen minutes, I'd spotted one of the things. They were about the size of a rabbit all right, and what was more they looked considerably like one of the earth type rodents—long ears, nub of a tail. I watched it for some time through the small glass I'd borrowed from Mike.

It was evidently eating the bark, and possibly the wood as well, of a stunted, rugged looking Martian tree which seemed to be growing out of almost solid rock.

The boys had said that there were a lot of zloors around so I didn't have to worry about conversion. I took up the rifle, aimed carefully through the scope and squeezed the trigger. I was interested, eventually, in getting a live zloor, but it wouldn't hurt to have a closer look at one of the things to help me in planning my campaign.

The gun snapped and I could see the tiny bullet spank into the little animal's side. I'd got him!

But something didn't look right. I took up the telescope again and peered through it. The zloor was still eating.

That stopped me. I could have sworn that I'd hit it, right amidships.

I aimed even more carefully this time, for its head, and squeezed gently. That shot, too, hit dead center.

But the zloor didn't bother to stop its feeding.

I sat there a long time staring at it. Finally I snorted inwardly. Obviously, this was what had been stopping the others—this animal had some very effective natural body armor. Well—there is more than one way of skinning a zloor, as well as a cat.

I picked up the rifle and headed down toward the tree and the animal that was devouring it, figuring to get as close as possible with the idea of getting a really good look at the bulletproof beastie. I wished, now, that I'd brought my .257 Roberts instead of the .22 Hornet.

At first I was careful in my approach, slipping from cover to cover; but as I got closer it became evident that the zloor wasn't particularly timid and that as far as it was concerned I could come as near as I wanted.

I stood off about five feet and watched it for a long time. Once it looked up and over at me, but then went back to the tree in which it was making a respectable hole.

I tried once again with the rifle, aiming carefully right behind its ear. The gun snapped, and the bullet thudded—but the zloor ignored it.

"Holy Wodo," I snorted. "He's really bulletproof."

In fact, he was more than just bulletproof. The shock of the impact of the high powered twenty-two hadn't even bothered him, it wasn't just a matter of the bullet's inability to penetrate the hide.

"Well," I told myself. "Let's see just how close I can come before it runs off."

I walked up to him cautiously. He didn't move. In my surprise, I even prodded him gently with my shoe. He still didn't move. He looked up at me again, his eyes a wistful yellowish color, then went back to his meal.

I shook my head, wondering if I was still suffering from the effects of the woji binge, or what. This was just too easy—maybe it was a sick one or something.

I reached down and grasped it by the ears and started to pick it up.

Have you ever tried to pick up something and found out it either weighed considerably more, or was fastened to the floor? That's what happened to me. With Martian gravity what it is, I figured I'd have a weight of possibly one earth pound of lift. Instead, I nearly broke my back—and the zloor still didn't budge.

I put more pressure to bear, all my strength—and the zloor complacently went on eating.

Hands on hips, I stood above the rabbit-like animal and stared at it.

Finally, I muttered, "More than one way to bring home a zloor," and, taking my gun by the barrel, I swung it viciously down at the gentle looking little animal—feeling like a heel as I did it.

I might have saved my feelings, because two seconds later I was gazing wide-eyed at the shattered stock of my rifle and the zloor was still eating away at the tree.

I tried just one more experiment before I called it a day. I put the rifle barrel under him and tried to pry him off the ground. The zloor still ignored me, but the steel barrel bent under the pressure. The animal hadn't budged.

Without knocking, I walked back into Mike Holiday's room. He was lying stretched out on the bed, his hands behind his head, staring at the ceiling.

He didn't need to look at me. He said, "Nap, you are now a full-fledged member of the zloor club."

"What does one of those things weigh?" I snapped.

"Hey, red-head," he grunted, "don't take it out on me, I didn't invent them. Far as I know, nobody's ever weighed one, but it's been estimated that they go about five tons here on Mars. Six times that on earth."

"That's insane!"

"Sure is. That's why the government wants one so badly. Just isn't natural for such an animal to develop in the solar system."

"Or anywhere else!"

He got up on one elbow and grinned over at me. "The theory is that it's a life form from some planet belonging to a white dwarf star. Some time ago a guy named Adams at the Mount Wilson observatory, back on Earth, estimated that the density of some of the white dwarfs was two thousand times greater than platinum. I'm not much up on it myself."

I scowled down at him. "How'd it get here?"

He was serious now. "That's the reason the government wants one so badly, Nap. They want to get it to their laboratories and find out everything they can. There only seems to be one possibility, though."

"What's that?"

"If it is alien to the solar system and from a white dwarf's planet, it might have been brought here deliberately and left as a guinea pig."

I began to say something there but he held up a hand to stop me. "Possibly an exploring spaceship from the alien planet was looking for colony sites. When it got to our solar system it left some of these animals with the idea of coming back in a few thousand years or so to see if the zloors were able to adapt themselves to the conditions existing here."

I ran my tongue over suddenly dry lips. "You mean that if the zloors can live in our solar system, then these more intelligent aliens would figure they could use our sun system for a colonizing project?"

He nodded.

"Holy Wodo," I said. "No wonder they want some specimens to work on back on Earth."

He relaxed again. "Well, at the rate we're going, it'll be a long time before earth laboratories ever have the opportunity to mess around with our pal the zloor."

I got a chair and sat down facing him and said seriously, "Mike, brief me on what you and the other fellows have tried."

"You don't have to ask. That goes with membership in the club," he grinned. "Among other things, we've tried building a steel box around one of them with the idea of putting wheels on it later."

"That sounds good."

"Uh huh. The trouble was that when the zloor felt like moving he walked right through the side of the steel box like you or I'd walk through a wall of tissue paper."

"How about poisoning one?" I rapped. "You could get a dead one back a lot easier than—"

"They don't poison," he said, "and from what we can figure they're practically immortal. We have never found a dead one."

"What'd'ya mean, they don't poison?"

"Just that. Nap, that animal can eat anything organic and thrive on it. Evidently, no poison that nature has ever produced affects it. At least, none of us have been able to dream one up."

"How about narcotics, something to dope it?"

He shook his head. "To begin with, some of these Martian plants produce narcotic effects that make the products of our poppy look like food for babes; but the zloor takes them in its stride. It's really got a cast iron stomach. We've never been able to locate anything it won't eat and enjoy eating."

I didn't say anything for a long time. Then, "A Bazook-rifle would kill one."

"Sure," he said, "and splatter it all around the scenery at the same time. The laboratories need a good specimen."

There was another long silence. Finally I said, "Why in the name of Wodo don't they sink into the ground if they weigh as much as all that?"

"They would, only they make a point of walking on rock. That must be one of the things that limits their spreading even more widely. They have to be able to forage on ground that supports very little vegetation."

"You could lift one with a derrick."

He said, "This is the fifth time I've been through this. Every guy that Westley Marks sends up here asks the same questions. Sure you could lift it with a derrick if the derrick was big enough. Do you have any idea of what it'd cost to bring a derrick of that size to Mars?

"And that's not the only thing, either. These zloors are gentle as lambs, but they hate to be confined against their will. That derrick'd have to have some awfully strong equipment to keep the zloor from breaking loose and ambling off. There's other angles there, too. Suppose your derrick did lift him into the shuttle. When you got the shuttle up to the space station, how'd you move the zloor from the shuttle to the station and then from the station to the rocket for Terra?"

He go up from the bed and went over to a little table to return with a bottle and a couple of glasses. He poured two drinks and handed me one. "Here," he said, "you look like you could use a quick one. Have a hair of a dog that's going to bite kert out of you before you ever leave Mars."

I grated, "I could stand the rest of it, but what burns me up is that makron Westley Marks. Here he is getting rich on the project. Besides what he makes from the government, he's bet every one of us so much that we'll all be out our life savings when we go back."

"Brother Nap, you have said it," Mike Holiday said feelingly. He tilted the glass to his lips and drank deeply. I was right behind him.

It was more than two years later when I walked into the office of Westley Marks. I noted with pleasure that he still looked as aristocratic as ever.

"Ah," he said, "Mr. Napoleon Prescott. As I recall, the last time we met you objected to my calling your namesake a 'bust.' Don't tell me that we have an additional bust in—"

I loved it. I loved every word of it. And he must have seen that I did.

"What are you grinning about?" he barked. It was the first time I had seen his poise disturbed.

"Frankie," I told him, "is at the spaceport right now. Johnny will be down on the next shuttle. As you can imagine, the shuttle was pretty well strained to capacity to bring even one at a time. It was no trouble in space of course, since they were weightless in free fall, but entering the gravitational—"

He put his hands on the top of the desk and half came to his feet. His eyes were wide. "Who are Frankie and Johnny?"

I feigned surprise. "Frankie and Johnny are sweethearts—a couple of zloors, in this case. Remember? You sent me for them. I thought a male and a female would be best."

He slumped back in his chair. "You aren't lying?"

I didn't say anything.

"How ... did you do it?"

"With peach pits," I said.

"Peach pits!"

"Peach pits. They like apricot pits too, and sometimes prune seeds."

"What in the world are you talking about, Prescott? Have you lost your mind?"

I opened the humidor on his desk, took out a cigar, smelled it, bit off the end, lit it, and took a deep puff before answering him. I settled down into a comfortable chair and pointed the lighted end of the cigar in his direction.

"Between one or the other of us we had tried everything, everything. I realized finally that it would have to be an entirely different approach."

I took another satisfying drag on the cigar, then went on. "I tried lettuce, cabbage, corn, string-beans—everything in fact that the hydroponic tanks on Mars could supply in the way of earth type