CHAPTER V.

SETTING SAIL.

Their future constant companion joined the father and son, as might be expected, at Mooney’s Tavern. He had no leave-takings to subdue the boisterous spirits in which he set out on an expedition that was to make a rich man of him. His brothers and sisters were married, and had lost all interest in him long ago. They were even glad that he would no longer be a daily disgrace to them. He was very grand with Mr. Gilman’s money, and expected, of course, to drink to their success in a parting glass at Mooney’s. He had drank to it so often already that morning, that it was doubtful whether he would be fit to start on the journey. It had the effect of making him unusually good-natured, fortunately, so that he took Mr. Gilman’s refusal with only the complacent remark, “more fool he.” The stage did not make long stoppages so early in the day; away they drove again—the tavern, the post-office, the white meeting-house on the hill, disappearing in turn, and then the young traveller felt that home was really left behind.

He was very quiet, he could not help it.—The day was exceedingly cold, and the road, for miles together, dreary and uninteresting. The noisy laugh of Colcord troubled him, while he thought of his mother and the girls. This could not last long, as the stage filled up, stopping now at a farm house, where a place had been bespoken for its owner the day before, or receiving a passenger at some wayside tavern. Sam began to feel all the dignity of being a traveller himself, and particularly when he saw how much the strangers were interested, hearing that they were bound for California. Colcord talked to every one, and made himself out the commander-in-chief of the expedition. He was going to “invest,” as he called it; he expected to see the time when he could buy up the whole of an insignificant little village like Merrill’s Corner!—And then the most incredible facts were related, exaggerated newspaper reports given, as having happened to the uncle, or cousin, or friend of the speaker. When they came to a tavern, Colcord was the first man out, strutting around the bar-room, and asking all his fellow-passengers to drink with him. Even Mr. Gilman seemed ashamed of his partner, as he loudly proclaimed himself to be.

Sam went to bed at Concord that night, wondering if New-York could be larger, or have handsomer houses, and what they were doing at home. It seemed as if months had passed since bidding them good-bye. Then came the novelty of a railroad, the hurried glimpse at Manchester and Lowell, with their tall piles of brick and mortar, the loud hiss of steam, and clanking of machinery. How busy and restless all the world began to seem, and how far off the eventless village life, which had till now been a world in itself.

Colcord did not let them lose a moment’s time. He had found out on the journey, that no ship was to sail from Boston for more than a week. A week, he said, would give them a long start; as they had the money, they might as well push through to New-York, where whole columns of vessels were advertised.

The morning of the third day after leaving home, Sam found himself following his father and Colcord along the crowded wharves of this great city, going to secure their passage.

The “Helen M. Feidler,” was the unromantic name of the ship Colcord had selected. She was to sail first, and the handbills pasted along the corners, described her as nearly new—fast sailing—with every possible accommodation for freight and passengers. The owners said she would make the voyage in half the usual time, and if they did not know, who should? In fact the clerk, or agent at the office, gave such a glowing account of her wonderful speed, the excellent fare, and the rush of people to engage their berths, that Mr. Gilman was all ready to secure three cabin vacancies that happened, by the most fortunate chance in the world, to be left. He had even taken out the old-fashioned leather pocket-book, in which the bills were laid, when he saw Colcord making signs to him not to be in too much of a hurry. The clerk assured them, his warm manner growing very cold and distant, as he replaced his pen behind his ear, that the next day would probably be too late. Sam did not understand what Colcord said to his father, but almost as soon as they were in the street, they told him he had better stroll around and amuse himself; they were going to look at the ship, and see if all that had been said was true.

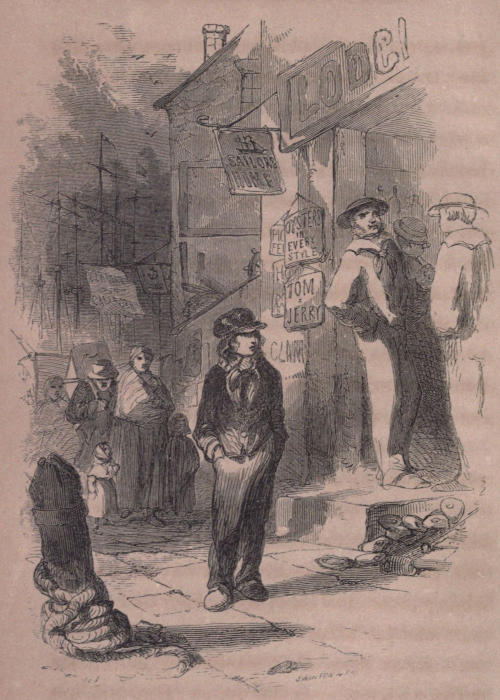

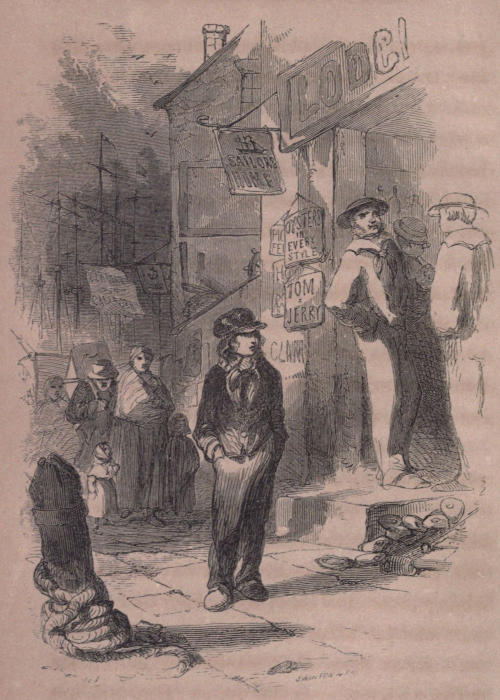

“HE STROLLED ALONG THE WHARVES.”

This was certainly very reasonable. Sam wondered, at the same time, what had made Colcord so suddenly cautious, and why they did not take him with them. However, he strolled along the wharves, where all was new to him; the inviting eating saloons, with their gayly-painted signs, the sailors in their blue and red shirts, and rolling gait, that came out and went into them, the tall warehouses of the ship-chandlers, with the piles of ropes, and what seemed to him rusty chains, and useless lumber, scattered about the lower floor. It was a bitter day, and seemed doubly cold and disagreeable in the absence of snow, which only was found in dirty and crumbling piles out on the wharves or along the edge of the frozen gutters. The signs creaked and clanked in the wind, that came sweeping with icy chillness from the river; and the bareheaded emigrants, women and children, that came trooping along the sidewalk, looked half frozen and disconsolate. Still it was new and wonderful, and so were the rows of vessels, schooners and brigs, that lined the docks, some receiving and others discharging their cargoes, with a hurry and bustle of drays, and creaking pulleys, and a flapping of the sail-like canvas advertisements, fixed to the mast, that told their destination, and their days of sailing. The black hulls and dirty decks did not look very inviting; but, of course, the wonderful Helen M. Feidler, did not in the least resemble such uncouth hulks as these!

How he did wish for Ben as he walked along, trying to shield his face from the wind, with nobody to ask a question of, or tell his discoveries and conjectures to! He wished for him more than ever when he inquired his way back to the lodging house, in which they had left their chests, and found his father had not yet returned. It was a cheap place of entertainment, and chosen by them because near the water. Sam did not think it nice nor comfortable in the uncarpeted sitting-room, scarcely any fire in the dirty stove, and nothing to look at but an old file of newspapers on the baize-covered table. But that was better than the bar-room and its unwelcome sights and sounds.

He expected his father every moment, and told the waiter so, when he asked him if they would have dinner. The afternoon came on, still lonely, dark and gloomy. He began to be anxious for fear they had lost their way, or perhaps been robbed, and carried out to sea,—he had heard of such things. Hungry, and tired and lonely, he laid down on the long, wooden settee, and fell asleep, dreaming that he saw his mother, and made her very happy by telling her that his father had resisted all Colcord’s endeavors to get him to drink, and talked about her every time they were alone together.

It was very late—nearly midnight—before the men returned. They were quarrelling violently on the stairs, and poor Sam instantly knew that his father had again been led into temptation. He did not know until the next day what a misfortune this had proved. When his father awoke, haggard and sullen, it was to charge Colcord with having robbed him of every cent the pocket-book contained, more than half of all he possessed. Colcord’s own poverty disproved this charge. Between them, there was just enough to take a steerage passage for the three, and paying their bill at the lodging house, but a few dollars were left.

They had not yet purchased the necessary tools and stores for their business; with the exception of a newly invented patent gold-washer, in which Mr. Gilman had rashly invested a third of the sum originally intended for their outfit, on their way to the wharves, there was nothing to rely upon when they should arrive out. Colcord tried to get him to exchange this for the less expensive picks and spades; but Mr. Gilman was stubborn and dogged, as he always was under the influence of strong drink, and insisted on what he considered a fortunate speculation.

It was in this way, after all his father’s pride and spirit on leaving home, that Sam, with his two still unreconciled companions, was entered as a steerage passenger on one of those very vessels that he had considered so unpromising at first sight. He tried to write a cheerful letter home, the day of sailing, describing what he had seen, but saying as little as possible about his father, or the vessel, that he could not think of without disgust. It was indeed a comfortless prospect, to be shut up for months in that dreary-looking steerage, so dark and stifling, so crowded with human beings of every grade and country.

The same glowing description was given of the speed and safety of the “Swiftsure;” but Sam began to doubt even the merits of the Helen M. Feidler, when he read column after column, in which barks, schooners and brigs up for California, were advertised to possess every advantage that could possibly be desired. It was his first great lesson that promise and reality are by no means the same thing.

Boy as he was, and hopeful as he had always been, he sat down disconsolately on his father’s chest, and tried to realize all that had befallen him. The place described in the advertisement as “large, roomy, well lighted and ventilated,” seemed to him dark, crowded, and suffocating. The space between the rows of bunks, as the slightly built berths were called, was piled with chests and boxes, over which each new comer climbed, and fell, and stumbled along, venting their annoyance in oaths and imprecations. The air was damp, at the same time so close and heavy that he could scarcely breathe. A fear of stifling when night and darkness came, made him start up and rush on deck, while it was yet possible to do so. They had already moved out of the dock in tow of a small steamboat, that was to take them down the bay, and carry back the friends of the cabin passengers, who helped fill the decks. There was scarcely an inch of plank to stand upon, or an unobstructed path to any part of the ship. Water-casks, fresh provisions for the cabin table, crates of fowls, the cackle adding to the general uproar; chests, boxes and trunks of the passengers, and freight received up to the last moment, were scattered, piled and packed in what seemed hopeless confusion. If there was dreariness and heart-sinking in the steerage, the cabin made amends with its uproar and jollity. Every one seemed to be of Colcord’s opinion, that too many parting glasses could not be, and wine and brandy flowed as freely as water.

It might have seemed a festival day to Sam, if the sun had shone and the shores been covered with summer foliage; but the sky was in those close racks of clouds, so often seen in winter, chilling the very sunlight to transient watery beams. Cakes of ice, dirty, huge and discolored, were floating in the bay, crashing against the puffing little steamboat, with every revolution of the wheel. No golden horizon could gild the chilliness of the whole scene, or make it promise brightness to come.

It was late in the afternoon when the steamboat cast loose from them, and the ship, with every sail set to the strong breeze, went on her way alone. The friends of the cabin passengers departed with cheers on each side, while some on ship-board went below to write one more hasty word of farewell to still dearer ones left behind. The pilot, bearer of these messages, resigned his brief command to their captain, and left them last of all. The low line of coast—the Neversink highlands—that last glimpse of home became indistinct in the wintry twilight, as the swell that bore them on sank into the long, rolling, foam-crested waves—the boundless expanse of ocean.

The discomforts of the inevitable sea-sickness past, Sam began to find even the steerage endurable. It was crowded to be sure, and his fellow-voyagers were many of them quite as disagreeable as Colcord, who formed quantities of new acquaintances, and was so good as to trouble them very little with his society. After daylight,—and once accustomed to the rolling of the vessel, Sam slept as sound in his bunk as when his mother came to tuck in the bed-clothes in the garret chamber,—he saw very little between decks, until night came again. He made friends with the cook in the galley, and the sailors in the forecastle, where he was a welcome visitor. There was a never-ceasing interest in the long yarns which the sailors told of their various voyages in every quarter of the globe, and their numerous adventures in port; some of which did not speak much for their morality, I am sorry to say. It was as good as six volumes of Sinbad, as many of Munchausen, and libraries of Gulliver. Sam watched all their ways with the most lively interest, and considered them the best fellows that ever were born. “How he should like to astonish Ben!” he used to think, as he sat on deck, watching them unravelling the tarred ropes for “spun-yarn,” or in the dim light of the forecastle, while they cut and made, and mended their wide pantaloons, or overhauled the thick clothes provided for their passage round the Horn, a prospect that did not seem very agreeable to them. He found himself adopting their peculiar gait, and practising from a large collection of sea-phrases. They taught him to climb the rigging, the names of the different sails and ropes, and the meaning of the curious orders sung out by the captain or mate, that at first had seemed like a foreign language. It was all so new and exciting, particularly when he came to understand the working of the ship, that he wondered what people meant when they talked of the “monotony of sea-life.” It doubtless was monotonous to the young men in the cabin, who slept, and ate, and drank, and lolled around the deck, sometimes with a book, sometimes hanging over the ship’s sides in perfect lack of occupation, “like cows in a pasture”—Sam used to say. He managed to get up a great feeling of superiority and pity, when he saw them turn out on deck after breakfast, looking so languid and sleepy. He had been up since sunrise, and seen the decks washed down and cleansed, seated in some part of the rigging, above the unceremonious flood that followed his promenade on deck. It was his delight to follow the sailors to the galley for their kids of beef and cans of coffee—what an appetite he always had for the “hard tack,” and meat almost as unimpressible to the teeth, that fell to his own share! The poor fellows in the cabin were starving by their own account, and thought as longingly of the abundance and variety of the tables at Delmonico’s and the Astor, as ever the children of Israel in the desert did of the flesh-pots of Egypt!

Many good mothers would have been troubled at this constant companionship with men they are accustomed to think of as degraded beings; but for a boy with Sam’s disposition, it was far preferable to the example of the more refined circle in the cabin. Sam knew that the oaths and honestly told “scrapes” of the sailors were wrong. There was no concealment intended, and it was easy to distinguish good and evil, when so broadly marked.

The twenty cabin passengers, mostly young men, who had led idle and dissipated lives in large cities, had a code of morals, that would have had a more secret and fatal influence.—Their conversation over the card table, the unending games, in which money was always staked to make it exciting, would have had a much worse effect. Sam knew that almost any sailor would drink when it was possible to do so, and had heard the habit spoken of as the worst which they were given to. He might have thought his mother was mistaken in the harm, after all, if he had seen the daily excesses of the captain’s table, and educated men boasting of the quantity of wine they had, or could carry, without being considered intoxicated. Their recklessness of any thing good and holy was appalling, and Sam would not have wondered so much at one of them, who used to go aloft to the cross-trees every fair day, and read or muse hours over his Bible, if he had heard how jestingly the sacred volume was named by the rest.