CHAPTER XI.

THE FATHER AND SON.

Sam was always up at the earliest light, and busied himself about the tent, preparing breakfast, which was generally ready before Mr. Gilman woke. The first warning he had of his father’s illness was seeing him toss restlessly on the earthen floor of their tent, moaning and muttering in his sleep.

“I’d lie by to-day, if I was you, father”—he said, bringing a tin cup of coffee, as Mr. Gilman sat up with a start, and looked wildly around him. “I can wash that pile out alone, and to-morrow’s Sunday. One day’s rest will set you right up again.”

“Who’s talking about resting! I don’t want rest! I ain’t sick, I tell you, I ain’t sick, who said I was?”

Sam was still more alarmed at the quick, almost fierce, manner in which his father spoke. “Nobody said so, sir,” he answered as quietly as he could. “Only you know how tired you were last night, and you talked some in your sleep.”

“Did I? What did I say?” Mr. Gilman began dressing with trembling hands, the matted hair falling over his thin, sunburnt face, and his blood-shot eyes glaring around the tent, with the wildness of fever. “What did I say, Sam—why don’t you answer me? Did I tell you somebody had stolen every cent? Don’t let them know it, Sam, the rest of them, will you? I mean it shall be two thousand dollars before the week’s out. Some rascal or other will track it yet—I know they will. There’s Tucker, don’t tell him; he wanted to know yesterday, how things stood. His pile don’t grow so fast just by hard work,—yes, it’s all gone, every cent—ain’t it hard, Sam?”

“I guess you’re mistaken, father,” Sam said, soothingly. “It was all right last night, don’t you remember? If I was you, I’d just drink some coffee and lay down awhile—you’ll remember all about it by-and-by. It ain’t time to go to work yet, any way.”

But Mr. Gilman would not be persuaded to lie quietly. He insisted on following Sam to the pile of earth they had prepared for washing out, and plunged knee-deep into the water, as if the coolness would take way the fever heat. It was the very worst thing he could have done, for the fever was followed by chills, and though he worked more than an hour with unnatural strength, it left him at once, and he laid down as helpless as a child, in the very glare of a hot sun.

He had been muttering to himself all the while, and his wild gestures drew the notice of those working around him. Sam was bending over his father almost as despairingly as he had done on the plains, trying to rouse him, when he heard some one say—

“I thought the old man needed looking after the last two or three days. Bear a hand, and we’ll carry him where he can lie more like a Christian.”

It was a young man Sam liked best of any in the camp. He was a general favorite; for, with his careless manner, and rough ways, there was an unselfish, generous temper, shown in numberless good turns, to those less experienced or less fortunate than himself. Nobody knew his real name, but they all called him “Major.” His costume was rather peculiar, even for the mines, his red flannel drawers and shirt being girt by a crimson military sash. For the six weeks since his arrival at Larkin’s Bar, he had not been guilty of the extravagance of a pair of pantaloons; it was the only economy, however, that could be set down to his credit, as the store-keeper could testify. His eyes and teeth were almost all that could be seen of his face, a mass of brown, waving hair falling over his broad forehead, and his heavy beard reaching almost to his sash; but the eyes had always a good-natured smile, and his teeth were even and brilliantly white.

“Well, you’re not as heavy as you might be, are you, neighbor?” he said, lifting Mr. Gilman, as if he had been a child, when he found he was unable to assist himself. Sam followed with a brandy-flask, some one had brought forward; brandy was both food and medicine to most of them. He had never seen severe illness before, and was entirely ignorant of what ought to be done. There was no physician within miles of them, and no medicine except stimulants, if there had been. The brandy was, perhaps, the best thing Mr. Gilman could have taken just then—so weak and exhausted; but when the fever came back at night, more violent than ever, Sam could only bathe his forehead and hands with cold water, while he listened to his wild ravings.

The gold seemed to haunt Mr. Gilman the whole time. He assured Sam, over and over again, that it was all stolen, every cent of it, in the most pitiful tone, and then the expression of his face changed to cunning, and he would whisper—“We’ll cheat them all, Sammy, Tucker and the rest. I guess your mother can get along, don’t you? She knows how to manage, and Abby’s a smart one. I guess we won’t send just now; you don’t mean to make me, do you, Sammy? It might get lost, and none of us would be better off, would we?”—or hours of lethargy followed, from which it was impossible to rouse him, the convulsive motion of his hands, or his vacant, rolling eyes, terrifying the solitary boy.

The miners came to offer any service, with their sincere, hearty kindness, but there was nothing to be done, and their time was too precious to be wasted. The Major came oftener than any of the rest, and all that he advised Sam tried to do. It was a relief to be busy about something, for though he did not think his father’s life was in danger, it was very hard to see him suffer so. The Major talked as encouragingly as he could, and told him not to be down-hearted; but the next week dragged very slowly, and he could not help being discouraged, as the fever and chills continued. Mr. Gilman’s frame wasted, and his sunken eyes and haggard face were painful to look at, even when at rest,—and then came that last awful change, which all but the love-blinded watcher had foreseen from the first.

Poor, lonely boy! He could not believe it was death, though the wan, shadowy look startled him, as he stooped down to moisten the parched lips with water. He left the sick man alone for the first time, while he went to call assistance, for night was coming, and he thought something might be done or wanted before daylight.

It was too late for earthly help. The men knew it was death, they were only too familiar with that fixed and rigid expression. They spoke in low voices to each other, and did all that was to be done, almost as tenderly as women, thinking, perhaps, that their turn might come soon. Sam watched them, following every motion, but he did not hear half they said to him, or scarcely understand what they were doing. The shock was too sudden for boyish grief or fear.

They went away again when all was arranged for the simple burial; for even the kind-hearted young man who had been with him most, felt it was best to leave the boy alone. The moonlight came in through the opening of the tent, and made every thing dimly visible, as he sat on the ground, by that stiff, motionless form. He put his hands over his face, and tried to think. His father was dead. He had heard them say so. His mother’s husband,—Abby’s father—Hannah’s father! They could not see him again. They were thinking about his coming home, and they would look for him, but it was no use. He felt it would kill his mother, when she came to know about it, and it seemed as if he could hear Abby’s passionate crying, and sobs, when she heard the dreadful news. She had always been her father’s favorite, without any jealousy from the others, since the first moment that her soft baby arms were wound around his neck.

He wished that it was him, instead of his father, who had gone, since one of them must die; it would not have made half so much difference at home. Then he lifted up his head from between his knees, and looked at his father’s face again,—only to sink down and rock his body slowly, as he thought on, and on.

If his father had died at home, how different it would have been. The whole neighborhood would have known Mr. Gilman had a fever. The doctor and the minister, and his mother, would have been by, and he might have known them, and talked about Heaven, and some one would have prayed.

Then Sam thought, what was living, after all, and what use was it to come into the world so full of trouble? Perhaps the thought was a prayer, for the answer came in the recollection of many things that he had read and studied in his Bible. His mother had explained to them again and again, how Our Father in Heaven permits us to have trials and troubles as long as we live, so that we shall not forget there is a better and a higher life. And there every one is told so plainly what is right and what is wrong; those who do right being happy, even in sickness or poverty. It was only natural in Sam to think for an instant, how much better it would have been for them all if his father had been as good and contented as their mother was, but that feeling was lost in the bitter one, that it was all over now, life was ended, nothing could be changed.

“Oh, mother, mother, mother,” the boy groaned, and he longed, as if his heart was breaking, to lay his head on her knee, and look up for comfort to her face, as he had often done in his childish troubles. “Dear, dear mother!” and the tears came at last, raining through his fingers, and taking away that dull stupor of pain from his heart. He was exhausted with his long and anxious watch, and a strange heaviness came over him, which he struggled against in vain. He did not mean to sleep, but he must have done so, for he roused himself up and looked around with a sobbing start. He had not forgotten that his father was lying dead beside him, that he was keeping watch for the last time—but he thought he had heard a stealthy footstep outside the tent, and that the shadow of a man fell across the entrance. But no one came, and there was no sound but the fretting of the river, as the moon sank behind the hills, and left him in darkness and solitude.

There was not time for grieving over the dead, or for more than the simplest burial rites, in that rude mountain life.

The men came again, at earliest light, and found the boy sitting where they had left him, his long hair falling over his face, bowed down upon his knee. Sam understood why they had come, and rose to follow them, though no one spoke a word to him, as they wrapped Mr. Gilman in the blanket on which he laid, and carried him away. His was not the only grave they had prepared at midnight, for other low mounds of earth marked a little slope, half way up the bluff. And here they laid him, with kindly, not loving, hands,—he was a stranger to them all, and but one solitary mourner stood near. There was no audible prayer, though no one can tell what thoughts or wishes passed through their minds, as the men stood silently for a moment, with uncovered heads, when their task was finished. It was but a moment, and then their voices, and their footsteps sounded down the hill, as quick and as careless, as if death could not reach them.

Sam thought they had all gone, but some one came and laid a hand on his shoulder. It was the Major, who said cheerfully—

“Come, come, my boy, don’t give up; you’ve got a long life before you yet.”

“A hard one,” Sam said, turning away his face even from those friendly eyes, and leaning his head against a tree. No wonder his voice sounded hopeless, for he was yet a boy, and thousands of miles from any one who knew him or cared for him, in the first great trouble of his life.

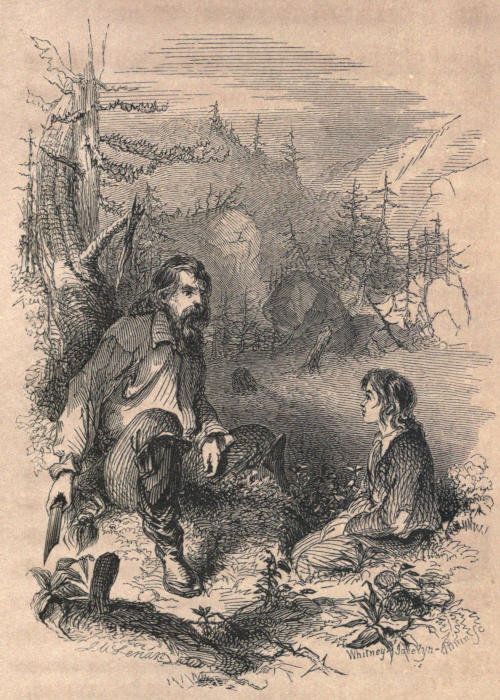

“It’s hard enough, anyhow, for that matter, but there’s no use crying over it. I suppose you think I’m a jolly dog—most people do.—Well, I haven’t seen the day for these six years, that I couldn’t thank any body who’d help me out of it. Let’s sit down here a minute and talk it over. Do you suppose any body is really happy?”

“Any body!” Sam repeated wonderingly, but he sat down on the grass beside his stranger friend, who began hacking the root of the tree with his knife as he talked. He forgot his own troubles, wondering what such a good-hearted, careless man could be miserable about.

But the Major did not seem disposed to talk any more about himself; only he said—

“I never had a brother. I don’t know how I’d feel towards one; but if there’s any thing I can do for you let me know it. I’d advise you to go home, if you’ve got enough to take you there. California’s not the place for boys like you.”

“I don’t know that I am different from other boys,” Sam began to say.

SAM AND THE MAJOR.

“Oh, yes, you are,” the other interrupted. “You don’t swear, and you don’t drink, you don’t gamble,—now I’d like to know what other boy of your age, would stand a voyage round the Horn, and three months in California, without being as bad as the rest of us. Boys are worse I think.”

“Not if they had such a mother as I’ve got!” and then Sam thought that his mother was all now,—and his heart sank down again, for there was the new-made grave,—he was fatherless and she a widow.

“I wish I had a mother—I wish I had any body to care for me, or any thing to live for. Go home, and take care of your mother, my boy—stay by her as long as she lives. You!—yes, go home and comfort her. See what gold’s done for your father—see what it’s doing for all of us, here in the mines. We live like savages, and we die like sheep. Your father was taken care of, and buried decently, that ought to make you thankful. I’ve seen men lie down by the road-side, with no one to give them a drop of water—with racking pain and thirst. And they’d die so, and nobody knew even their names, or where they came from. You must go home.”

Sam had not thought of what he was to do; but he did not need such urging to decide. He could go now,—he was free, his labor of love was ended! He almost caught his breath with the recollection, that there was nothing to keep him one day longer away from all the comforts of life, and among bad men. He was almost happy again—even when looking back to his father’s grave, for would he not leave death, and toil, and care behind him, and have a home, and be a boy once more!

“Well, good-bye, if I never see you again,” the Major said, when he found the boy was fairly roused. Sam had not noticed till then that he seemed to be ready for a journey, and a pack, such as a New-England pedler might carry, laid under a bush near them. His companion raised it, and secured it, with the long red sash, over his shoulder.

“I’m off, you see, I don’t know exactly where. If I did, I’d ask you to travel with me. You’d better start with the next team that comes in from Sacramento, and try a steamer this time if you can. I would anyway, I’ve had enough of the Horn.”

It was a brief, abrupt leave-taking, and Sam had not known him long, yet he felt as if the only friend he had in the country was gone, as he watched the tall figure disappear over the bluff above him. A little kindness had made him feel a great interest in this strange, roving man. But there are many such in California, who seem to have no settled plans, and nothing to live for, but the whim of the moment. Sam was thankful even in his loss, that he had so great a duty and pleasure before him, as to make his mother happy, and take care of his sisters. He was their only protector now. He was learning in boyhood what some live a lifetime to find out,—that the greatest happiness we can ever have in this world, is thinking more and doing more for other people than ourselves.