CHAPTER I.

BAD MANAGEMENT.

“Ain’t the stage rather late, Squire? I’ve been waiting round a considerable while now.”

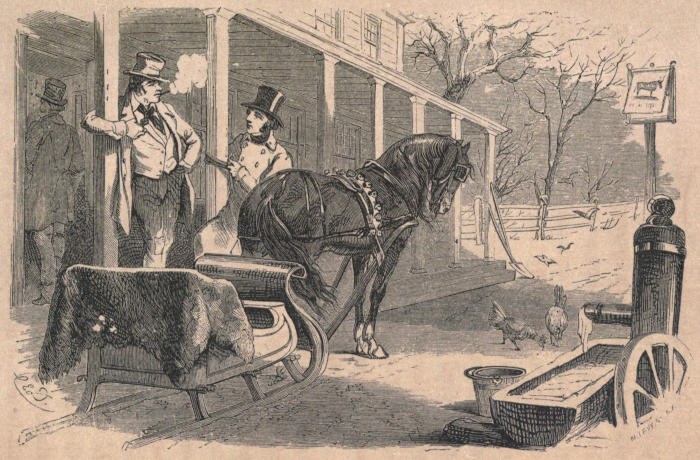

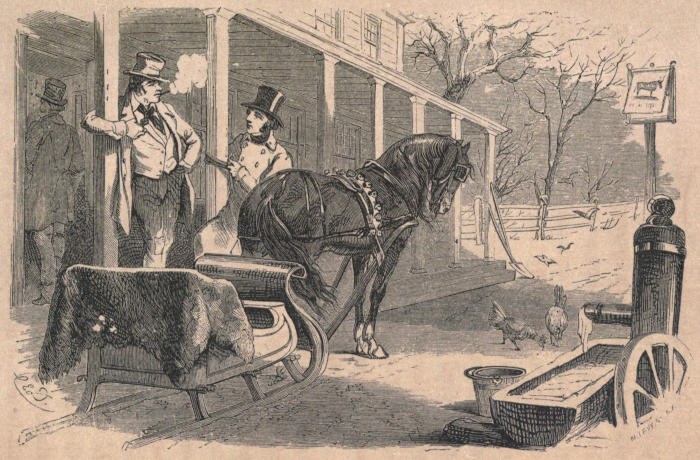

The “Squire” had just driven up to the Post Office, which was at one end of the village tavern, and a man hanging to a post that upheld the piazza addressed him.

“Perhaps it may be, I’m rather late myself; but I drove the long road past Deacon Chase’s. Do you expect any body, Gilman?”

“Well—I can’t say I do, Squire; but I like to see the newspapers, and hear what’s going on in the world, as well as most people, specially since the Californy gold’s turned up. I wouldn’t mind finding a big lump or so myself.”

Gilman chuckled as he said this, and set a dilapidated hat a little more over his eyes, to shade them from the strong light of the declining sun. No wonder they needed it; for they were weak and bleared, and told the same tale that could be read in every line of a once expressive face. The tavern bar had seen as much of him as the piazza. He knew by long experience the taste of all those fiery liquids, contained in the rows of decanters, and worse still, of many a cask of New England rum, dispensed by the landlord of “Mooney’s Tavern.”

“I’ve heard your wife’s father say there was gold buried on every farm in New Hampshire, if people only knew where to find it,” the Squire answered pleasantly, fastening his horse to the much used tying-up post; “there ought to be on what’s left of his, by this time—there’s been enough buried there.”

WAITING FOR THE STAGE.

The man, dull as his once clear mind had become, seemed to understand the allusion and the reproof it conveyed, for his face flushed even through deep unhealthy redness, as he walked off to a knot of idlers like himself. They stood with their hands in their pockets, and coats buttoned up to the chin—discussing the wonderful news that was then the only topic of conversation through the whole Atlantic coast, and even far in the backwoods, where much less of the great world’s doings came—the gold discovery in California.

At first it had been scarcely credited—many who were afterwards ready to stake life itself in gaining it, declared the whole thing a hoax, and ridiculed those who believed in it. But as month after month brought fresh arrivals, and more marvellous intelligence from the new-found El Dorado, even the endless discussion of politics was given up for this fascinating theme. So far, no one had gone from Merrill’s Corner, the name of this retired New England village; but many from neighboring towns were now on their way to “make their fortunes,” or lose their lives in “the diggings.”

The door of the post office had scarcely closed upon Squire Merrill, when the jingling of sleigh-bells and the quick tread of horses was heard coming up the hill. It was the stage-sleigh, that passed through from Concord every afternoon, bringing the eagerly expected mail and a few travellers, farmer-looking men, who were glad to spring out, and stamp their benumbed feet, the moment it drew up. One of them threw a morning paper into the knot of questioners, telling them rather abruptly to “look for themselves,” as they asked the invariable question, “what’s the news?” and Gilman, who was so fortunate as to seize it, was instantly surrounded as he unfolded the sheet.

The expected arrival was announced, in huge letters, at the top of the paper:—

ONE MONTH LATER FROM CALIFORNIA!!

ARRIVAL OF THE CRESCENT CITY.

HALF A MILLION IN GOLD DUST!!!

NEW DISCOVERIES MADE DAILY.

PROSPECTS OF THE MINERS CONSTANTLY IMPROVING!

And with a voice trembling with eagerness, the wonderful particulars were read aloud, interrupted only by exclamations of astonishment, more expressive than elegant.

Lumps of gold, according to these wonderful accounts, were to be picked up for the stooping. Some men had made a fortune in a single month, from steamer to steamer.

Every remarkable piece of good fortune was exaggerated, and the sufferings and privations, even of the successful, barely touched upon. There was scarcely enough shade to temper the dazzling light of this most brilliant picture. No wonder that it had all the magic of Aladdin’s wonderful lamp to these men, who had been born on the hard rocky soil of the Granite State, and, from their boyhood, had earned their bread by the sweat of the brow. If it dazzled speculators in the city, men who counted their gains by thousands, how much more the small farmer, the hard-working mechanic, of the villages, whose utmost industry and carefulness scarcely procured ordinary comforts for their families.

Just as the stage was ready to drive off again Squire Merrill came out on the piazza with several newspapers in their inviting brown wrappers, a new magazine, and one or two letters. There was of course a little bustle as the passengers took their seats, and the driver pulling on his buckskin gloves, came from the comfortable bar-room, followed by the tavern-keeper.

“More snow, Squire, I calculate,” remarked the sagacious Mr. Mooney, nodding towards a huge bank of dull-looking clouds in the west. “What’s your hurry?”

“All the more hurry if you’re right, Mr. Mooney,—I think you are; and somehow I never find too much time for any thing. Going right by your house, Gilman; shall I give you a lift?”

“Well I don’t care if you do,” answered Gilman, to the surprise of his fellows, and especially the hospitable Mr. Mooney. He had not yet taken his daily afternoon glass, and just before one of them had signified his intention of standing treat all round, to celebrate the good news from California.

The Squire seemed pleased at the ready assent, for it was equally unexpected to him, knowing Gilman’s bad habits. He did not give him time to withdraw it, for the instant the stage moved off, followed, in the broad track it made through the snow, the bells of both vehicles jingling cheerfully in the frosty air. It may seem strange to those unaccustomed to the plain ways of the country, especially at the North, that a man of Squire Merrill’s evident respectability should so willingly make a companion of a tavern lounger. But, in the first place, the genuine politeness of village life would make the neighborly offer a matter of every day occurrence, and besides this, the Squire had known Gilman in far different circumstances. They played together on the district school-ground, as boys, and their prospects in life had been equally fair. Both had small, well cultivated farms, the Squire’s inherited from his father, and Gilman’s his wife’s dowry, for he married the prettiest girl in the village. Squire Merrill, with true New England thrift, had gone on, adding “field to field,” until he was now considered the richest man in the neighborhood, and certainly the most respected. His old school-fellow was one of those scheming, visionary men, who are sure in the end to turn out badly. He was not industrious by nature, and after neglecting the business of the farm all the spring, he was sure to see some wonderful discovery that was to fertilize the land far more than any labor of his could do, and give him double crops in the fall; or whole fields of grain would lie spoiling, while he awaited the arrival of some newly invented reaping machine, that was to save time and work, but which scarcely ever answered either purpose. Gradually his barn became filled with this useless lumber, on which he had spent the ready money that should have been employed in paying laborers—his fences were out of repair, his cattle died from neglect.

Mr. Gilman, like many others, called these losses “bad luck,” and parted with valuable land to make them up. But his “luck” seemed to get worse and worse, while he waited for a favorable turn, especially after he became a regular visitor at Mooney’s. Of late he had barely managed to keep his family together, and that was more owing to Mrs. Gilman’s exertions than his own.

The light sleigh “cutter,” as it was called, glided swiftly over the snow, past gray substantial stone walls, red barns, and comfortable-looking farm houses. The snow was in a solid, compact mass, filling the meadows evenly, and making this ordinary country road picturesque. Sometimes they passed through a close pine wood, with tall feathery branches sighing far away above them, and then coming suddenly in sight of some brown homestead, where the ringing axe at the door-yard, the creaking of the well-pole, or the bark of a house-dog made a more cheerful music. There are many such quiet pictures of peace and contentment on the hill-sides of what we call the rugged North, where the rest of the long still winter is doubly welcome after the hard toil of more fruitful seasons.

Squire Merrill seemed to enjoy it all as he drove along, talking cheerfully to his silent companion. He pointed out the few improvements planned or going on in the neighborhood, and talked of the doings of the last “town meeting,” the new minister’s ways, and then of Mrs. Gilman and the children. Suddenly the other broke forth—

“I say it’s too bad, Squire, and I can’t make it out, anyhow.”

“What’s too bad, Gilman?”

“Well, the way some people get richer and richer, and others poorer and poorer the longer they live. Here I’ve hardly got a coat to my back, and Abby there—nothing but an old hood to wear to meetin’, and you drive your horse, and your wife’s got her fur muff, and her satin bonnet! That’s just the way, and it’s discouraging enough, I tell you.”

“My wife was brought up to work a good deal harder than yours, Gilman, and we didn’t have things half as nice as you when we were married.”

“I know it—hang it all—”

“Don’t swear—my horse isn’t used to it, and might shy—. Well, don’t you think there must be a leak somewhere?”

“Leak—just so—nothing but leaks the whole time! Hain’t I lost crop after crop, and yours a payin’ the best prices? Wasn’t my orchard all killed?—there ain’t ten trees but’s cankered! And hundreds of dollars I’ve sunk in them confounded—beg pardon, Squire—them—them—outrageous threshing machines.”

The Squire chirruped to his horse—“Steady, Bill—steady! Haven’t you been in too much of a hurry to get rich, Gilman, and so been discontented when you were doing well? You always seemed to have more time than I. I don’t believe I ever spent an afternoon at Mooney’s since I was grown up. I’ve worked hard, and so has my wife.” “Yours has, too,” he added, after a moment. “I don’t know of a more hard-working woman than Abby Gilman.”

“True as the gospel, Squire, poor soul!” and the fretful, discontented look on the man’s face passed away for a moment. A recollection of all her patient labor and care came over him, and how very different things would have been if he had followed her example, and listened to her entreaties.

“Why don’t you take a new start?” said the Squire, encouragingly, for he knew that if any thing could rouse his old companion it would be the love for his wife. “You’ve got some pretty good land left, and ought to be able to work. We’re both of us young men yet. My father made every cent he had after he was your age; and there’s Sam, quite a big boy, he ought to be considerable help.”

“Yes, he’s as good a boy as ever lived, I’ll own that—but hard work don’t agree with me. It never did.”

Gilman was quite right. It never had agreed with his indolent disposition. There are a great many children as well as men who make the same complaint.

“If a body could find a lump of gold, now, Squire, to set a fellow up again.”

“I do believe you’d think it was too much trouble to stoop and pick it up,” Mr. Merrill said, good-naturedly. He saw that California was still uppermost in his companion’s mind. “And just look at that stone wall, and your barn—it wouldn’t be very hard work to mend either of them, and I don’t believe a stone or a board has been touched for the last two years, except what Sam has contrived to do.”

Gilman looked thoroughly ashamed. With the evidence of neglect staring him in the face, he could not even resent it. He seemed relieved when the Squire drew up before the end door, to think that the lecture was over. There, too, were broken fences, dilapidated windows, every trace of neglect and decay. The place once appropriated to the wood-pile was empty, and instead of the daily harvest of well-seasoned chips, hickory and pine, a few knotted sticks and small branches lay near the block. One meagre-looking cow stood shivering in the most sheltered corner of the barn-yard, without even the cackle of a hen to cheer her solitude. The upper hinges of the great barn door had given way, but there was nothing to secure it by, and it had been left so since the cold weather first came. Every thing looked doubly desolate in the gray, fading light of a wintry day, and the blaze that streamed up through the kitchen window was too fitful to promise a cheerful fireside. Yet fifteen years ago, this very homestead had been known for miles around for its comfort and plenty.