CHAPTER V

THE ISLAND OF KHIOS

I find this fragment of memoirs written a year after the wreck of Lord Falmouth's yacht off the coast of Malta.

If I had the least literary pretension, I would not dare to say that these pages, written on the spur of the moment, depict very accurately the enchanting scenes in the midst of which I had been living for the last year in the sweetest of far-nientes.

In truth, the paradise I had created for myself seems to come again before my eyes, with its luxury of antique beauty, its palace of white marble gilded by the sunshine, its intoxicating perfumes coming from the orange groves that stand off against the blue sky that frames so magnificently the dark waters of the coast of Asiatic Europe.

That year should have been the happiest year of my life; for those few charmed days never caused me the least moral suffering. Not once did I feel any remorse, not once did I feel my heart.

But, alas! why was not the soul killed in such scenes of happiness? Why was not the mind overpowered by the senses? Why did thought survive the struggle?

Thought! that power of man! Man's true power, in fact; for it is fatal, like all powers.

Thought, that blazing crown, that burns and consumes the forehead that wears it!

According to my custom of classifying pleasant memories, I had entitled this fragment, "Days of Sunshine."

The light and careless tone that frequently appears in this souvenir offers a singular contrast to the sombre and heart-breaking events of the former chapters in this journal.

Days of Sunshine.

ISLE OF KHIOS, 20 June, 18—.

I know not what the future has in store for me, but, as I often said in my days of sadness and desolation, "one must distrust one's self more than one's destiny." I hope one day, as I read these pages, to be able to see again the smiling scenes amidst which I am now living so happily.

I write this the 20th of June, 18—, in the palace of Carina, situated on the eastern coast of the island of Khios, about a year after the loss of the yacht.

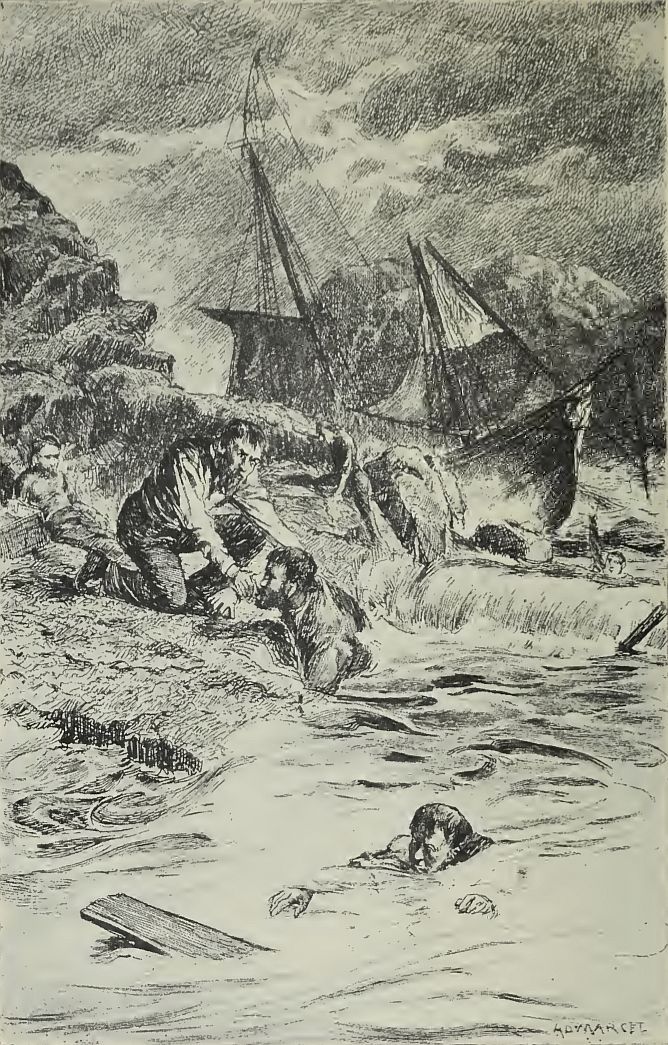

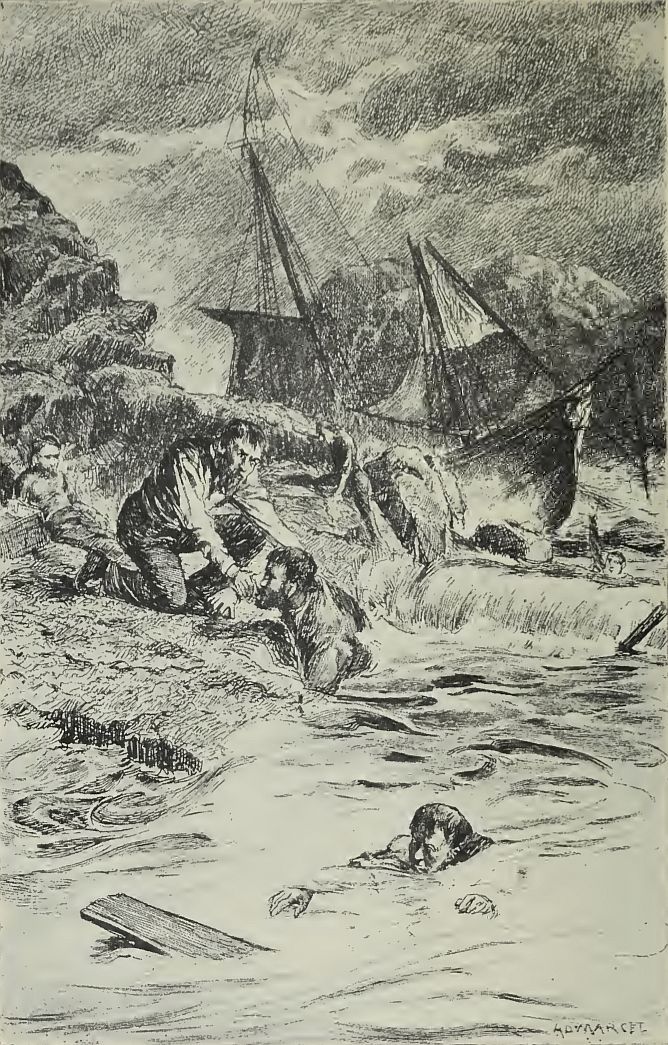

In that great peril, poor Henry saved my life. In spite of his wound, he was swimming vigorously towards shore, when, seeing me about to drown, for I could scarcely use my left arm, he seized me with one hand, and, fighting the waves with the other, he landed me on the shore in a dying condition.

My strength was quite exhausted by the excitement of the combat, by my wound, and by my desperate efforts at the time of the wreck; for I was for many long days a prey to burning fever and wild delirium from which I was restored to health by the excellent care of the doctor whom Falmouth had left behind.

I was so dangerously ill that I had to be carried to Marsa-Siroco, a little Maltese suburb, near the coast where the yacht had gone ashore. I remained in that village until my complete recovery, when the fever left me, and I was able to converse; the doctor told me the circumstances I have just recorded, and handed me a letter from Falmouth, which I copy in this journal.

"After all, my dear count, I prefer having saved you from drowning, to having put a bullet in your head, or perhaps having received from you a similar proof of friendship.

"I hope that the vigorous douche that you have received will have a good effect on you, and save you from another fit of insanity.

"My plans are changed, or rather become what they were at first. I desire more than ever to satisfy my fancy about that incendiary, Canaris; but as that diabolical piratical pilot (May he come to the gallows!) has wrecked my poor yacht, I have chartered a vessel at Malta, and am off for Hydra.

"Good-bye. If we ever meet again we will laugh at all this.

H. FALMOUTH."

"P. S. I leave you the doctor, for the Maltese doctors are said to be detestable. He will hand you a letter of recommendation to the lord governor of the island.

"Send me the doctor when you have no further need of his services."

I have become so stupid from the life of pleasure I have been leading, that I scarcely remember the effect this sarcastic letter had on me.

When I arrived at Malta I called on Lord P——, who showed me great courtesy. He caused active search to be made for the pretended pilot. That wretch had actually been at one time a member of the Royal Navy, but, for two years past, he had given up his position as pilot in the island of Malta.

A description of him was sent throughout the whole Archipelago, where he was supposed to be engaged in piracy.

At Lord P——'s I met a certain Marquis Justiniani, a descendant of that ancient and illustrious family, the Justiniani of Genoa, which had given dukes to Venice and sovereigns to some of the Grecian islands. The marquis owned many country places in the island of Khios, which had just been ravaged by the Turks. He spoke to me about a palace called the Carina Palace, built towards the end of the sixteenth century by the Cardinal Angelo Justiniani. The marquis had for a long time rented the palace to an aga. The description of the palace and the climate seduced me, so I proposed to go to Khios, to visit the palace and the park, and to rent or buy the place if it suited me.

We left together, and disembarked here after a three days' voyage. The Turks had left bloody traces of their passage everywhere; they were in garrison in the castle of Khios.

As I was a Frenchman, thanks to the firm attitude of our navy and our consuls in the Orient, I would be in perfect security in case of my deciding to dwell in Khios.

I inspected the palace, it suited me, and the business was settled.

The next day my interpreter brought to me a renegade Jew, who proposed that I should purchase a dozen beautiful Grecian slave girls, the spoils of the last Turkish raid in the islands of Samos and Lesbos.

Of these twelve girls, the eldest of whom was only twenty, there were three who were too refined and delicate to be put to work, and were therefore suitable for companionship.

The nine others, tall, robust, and very beautiful, could work either in the garden or in the house. He only demanded two thousand piastres apiece, about five hundred francs of our money.

In order to induce me to buy them, the renegade told me, confidentially, that a Tunisian officer, purveyor of the Bey's harem, had made him an offer; but that he liked to see his slaves well treated and so preferred selling them to me, knowing what harsh treatment the poor creatures would receive on board the Barbary chebek that was to take them to Tunis.

I expressed a desire to see the slaves.

The marvellous type of Grecian beauty has been so well preserved in this favoured clime, that, out of these twelve girls of every sort and condition, there was not one who was not really pretty, and three of them were perfectly beautiful women.

The bargain concluded, I sent the twelve women to the Carina Palace with two negro dwarfs, who were so deformed as to be positively picturesque, that the renegade presented me with by way of a contrast. They were all under the surveillance of an old Cypriote, that the Jew recommended as a housekeeper.

This sudden resolution to go to the Isle of Khios, and there to live at leisure, forgetting all things and every one, had been suggested to me a year ago, by the torturing remembrance of the great sorrow that overwhelmed me.

After my quarrel with Falmouth, whom I had so basely provoked, fully aware that I was unworthy of all generous affection, since I was constantly seeking the meanest motives, I believed that a perfectly sensual life would admit of neither these fears nor doubts.

What had made me so unhappy until now? Was it not from a dread of being deceived by my feelings? The dread of being mistaken should I allow myself to love? What, then, should I risk in devoting the remainder of my life to material love?

Nature is so rich, so fecund, so inexhaustible, that I can never weary of admiring her marvels, from henceforth I would doubt of nothing.

The perfume of a beautiful flower is not imaginary, the splendours of a magnificent landscape are real, beautiful forms are not deceptive. What interested motive could I impute to the flower that perfumes the air, the bird that sings, the wind murmuring softly through the leaves, the sea breaking on the beach, to nature, that unfolds so many treasures, colours, melodies, and fragrances?

It is true I will be all alone to enjoy these marvels, but solitude pleases me. I possess a deep sense of material beauty, which will be sufficient to make up for my want of faith in moral beauty.

The sight of luxuriant nature, of a fine horse or dog, a flower or a beautiful woman, or even a lovely sunset, has always given me exquisite pleasure, and though religious faith is unfortunately lacking in me, when I behold the splendours of creation I always feel transports of heartfelt gratitude towards the unknown power that heaps such treasures on us.

Regretting the faculties of which I am deprived, I will at least make the most of those I possess; and since I can not be happy through the mind, let me be so through the senses.

This I said to myself, and I was not mistaken, for never have I enjoyed such perfect happiness.

Falmouth was the best, the noblest of men. I know it. But when I compare my present life of felicity with the life of study and politics that Henry depicted in such glowing colours, the only thing I regret is the friendship that I destroyed by my awful suspicions.

Henry was quite right when he said that idleness was the source of all my miseries; so I have spent my time in the making of living pictures on which I can at all times gaze. It has taken much toil, and even study, to surround myself with all these marvels of creation, to get together all the scattered riches of this Garden of Eden.

Sages may tell us that these are but childish pleasures, but it is their simplicity that constitutes their pleasantness.

Serious immaterial joys are but perishable, while the thousand little pleasures a youthful nature can always discover in his reveries, though trifling and momentary, are constantly being renewed, for the imagination that produces them is inexhaustible.

Now that I have lived in such adorable independence, the life of society, with its exigencies, appears to me as a sort of order whose rules are as strict as those of the "Trappists."

I do not know which I would prefer, to be comfortably clothed in a serge gown, or cramped up in a tight coat; to breathe the pure fresh air of the garden I cultivated or the stifling atmosphere of a crowded salon; to kneel through the service of matins, or to stand all evening at some reception. In fact, I think I should as willingly choose the meditative silence of the cloister as the chatter of the salon; and say with about as much interest, "Brother, we must die," of the religious order, as "Brother, we must amuse ourselves," of the social order.

One thing only astonishes me, it is that I have been so long without knowing where true happiness lies.

When I think of the burdensome, obscure, and narrow life that most men impose upon themselves, through routine, in unhealthy cities, in damp climates, with hardly a ray of sunshine, without flowers, without perfume, surrounded by a degenerate, ugly, and sickly race, when they could live as I do without a care, as a monarch among the exquisite beauties of nature in a marvellous climate, I sometimes fear that my paradise will suddenly be invaded.

Thus I congratulate myself every day on my determination, my cup runs over with pleasure, my most painful remembrances fade away from my mind, and my soul has become so dulled from intoxicating joys, that the past has become a mere dream of misery.

Hélène, Marguerite, Falmouth, the remembrance of you is growing dim, far away, hidden under a beautiful cloud. I sometimes wonder how we could have caused each other so much suffering.

But what do I hear under my windows? It is the sound of the Albanian harp. It is Daphné, who invites Noémi and Anathasia to dance the national dance, the Romaïque.

May this description of all that surrounds me, the smiling scene that I gaze on while writing these lines, here in Khios, in the Carina Palace, remain on these unseen pages as a faithful picture of a charming reality.

No doubt these details would seem childish to any other than myself, but it is a portrait I wish to paint, and a portrait by Holbein, seen and painted with scrupulous fidelity; for, if ever I should happen to regret this happy period of my life, every stroke of the brush would be of inestimable value to me.