CHAPTER XV

THE SANTA MARIA

That incident, simple as it seemed to be, immediately cast its spell over the two girls. Barbara was so upset by it, whatever it was, that she could hardly keep her mind on the quilts and tidies. Cara simply sat down in one of the big rockers—it was there for exhibition purposes only—and she declared she wasn’t going to do another thing. Louise and Ruth were so curious they didn’t know what they were doing, so that the girls’ committee became suddenly very inefficient.

“It’s too late to do anything else anyhow,” Cara declared. “Let’s go home.”

To this all gladly agreed, all but Barbara. She insisted upon staying until her father called for her, but her real motive was to fix things up quietly when her willing but excited companions had gone. Every one wanted to help, but so many around merely lent confusion, and, as chairman, Barbara felt a certain responsibility.

So it happened she was still waiting and all alone when Miss Davis—the twin Miss Davis—came along trying to hide something beneath the folds of her old-fashioned black cape.

“I brought it in spite of her,” she confided to Barbara. “Sister Tillie is such a crank. But I was determined to show it.”

“Yes?” replied Barbara questioningly.

“Our great-grandfather made it,” she went on, meanwhile bringing forth from its hiding place a small wooden ship model.

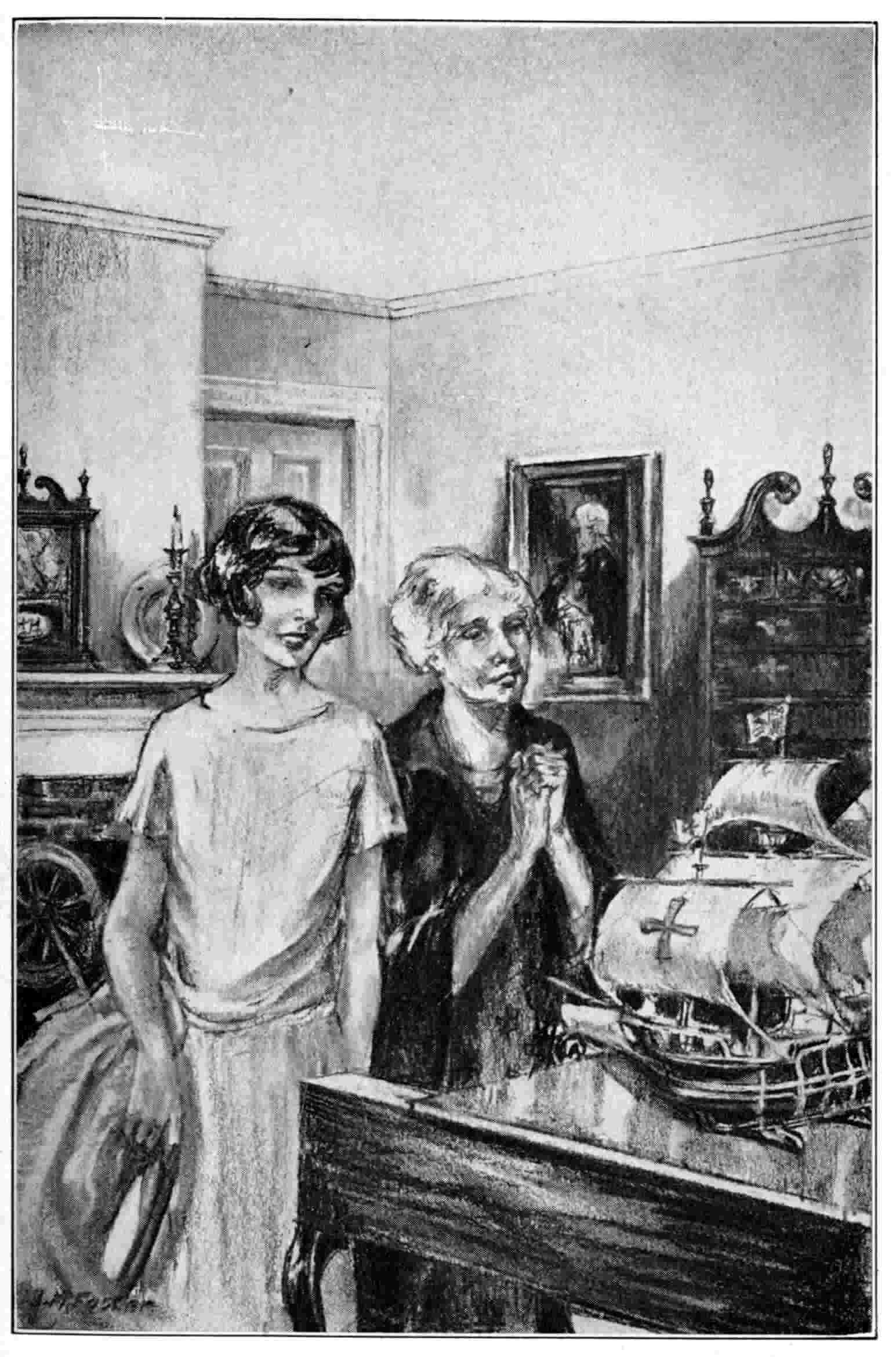

“Yes, it is lovely. And it’s priceless. It’s a model that was made in a war prison, and we have had all sorts of offers to sell it, but, of course, we would never part with it. You see, I’m so proud of it I just couldn’t miss the chance to show it off.”

“YES, IT IS LOVELY, AND IT’S PRICELESS.”

“I don’t blame you,” said Babs, still gazing with spellbound admiration at the little model. It was quite small but perfect in every detail.

“But Tillie is different. We’re twins, you know,” confessed little Miss Davis, “but never were two sisters more unlike. We never agree on anything. Where can we put the model so that it will be sure to be safe?”

“That’s a serious question,” answered Babs. “I wish all the ladies hadn’t gone. Some of them should have taken charge of this.”

“I’d trust your judgment further than I would theirs,” said Miss Davis generously. They had placed the model on the little spinet and it looked splendidly there.

“You see, Tillie wouldn’t agree that I should fetch it, but it’s as much mine as hers, and I was determined to get it here. As a matter of fact, she doesn’t know I did bring it,” confessed Miss Isabel Davis the other twin.

“Then, aren’t you afraid it will make trouble between you?” Barbara suggested.

“No doubt of it. But I don’t care about that,” Miss Davis insisted. “If I gave in in everything where’d I be? Now, let’s see where we could hide this. I wouldn’t dare to leave it on that spinet over night.”

“We’re going to have a watchman after dark,” Barbara informed little Miss Davis. “That is, the man in the next cottage has agreed to watch for us after he brings in his fish nets. He’s a fisherman, you know.”

“I’ve heard one did take that old place, but he’s a stranger around here, isn’t he?”

“The ladies seem to know him. They’ve bought fish from him and say he’s very reliable,” Barbara answered. “But I must hurry. Father will be here for me soon. Where will we hide the little galleon?”

“I’ve been looking around——”

“Here!” she exclaimed. “There’s a little cubby-hole built in the bricks back of this Dutch oven. It ought to be safe there.”

“Yes. That’s fine. You put it in. It will surely be safe there,” agreed Miss Davis, only too gladly.

Barbara picked the model up carefully and carried it over to the hearth. Then she turned on the little electric candle light that spread a soft glow over the dark bricks, opened the door of the closet and still more carefully set the war-time trophy within. Neither she nor Miss Davis spoke while all this was going on, for somehow she felt the importance of secrecy.

Then, just as Barbara turned to switch off the light, they both heard a noise.

“Some one at the window!” gasped Miss Davis.

“Yes, I heard some one,” admitted Barbara, “and it couldn’t have been Dad.”

But Miss Davis was at the door before Barbara had finished.

“There he goes,” she exclaimed. “And he’s that little Italian boy. The one whose father is in prison. Do you suppose he saw us?”

“Yes, that’s Nicky,” added Barbara, for she too was at the door and she could see little Nicky scampering along the sandy beach in full sight. “We don’t need to worry about him. He’s perfectly honest.”

“Land sakes, I hope so,” sighed Miss Davis. “For if anything happened to the Santa Maria I might as well never go back home. I couldn’t live a day under the roof with Tillie. She’s so fond of it. Perhaps, after all, I did wrong to fetch it,” she appeared to relent.

“If you feel that way about it you can come and get it again tomorrow,” suggested Babs, quite weary of the whole affair. “But I’m sure it would be lovely to have it in the exhibit. You know, the idea is to get materials that may be used in a little museum here eventually,” she explained.

“That’s just what I thought. And the Santa Maria belongs in a museum,” declared Miss Davis. “It’s perfectly foolish to have it locked up in our old cabinet. Yes, I’ll leave it and talk it over with Tillie. She’s as changeable as the wind, and perhaps I can talk her around. There’s that boy stopping at the fisherman’s place,” she interrupted herself. “He must know him.”

“Very likely, for Nicky knows the lighthouse keeper and others around here. He’s a busy little fellow and runs errands, you know,” concluded Barbara. “Well, here’s Dad. I just have to lock this door—everything else is locked. Won’t you ride out with us, Miss Davis?” she invited the small woman who was really very agreeable, and eager to help Barbara with the locking up or anything else left to be done.

“I’d be glad to, for I am tired,” admitted Miss Davis. “You see, I had to wait so late to get rid of Tillie. She was going in town all afternoon but I thought she’d never get started.”

Dr. Hale was waiting now, and it took but a few minutes for Babs and Miss Davis to climb into the car.

“Everything all right, daughter?” he asked solicitously, after greeting the guest.

“Oh, yes, Dads, all right,” Barbara replied a little wearily. “Miss Davis and I have a secret, something really wonderful to exhibit and we had quite a time hiding it,” she told her father briefly.

He laughed at that. “I don’t imagine the pirates will come ashore tonight,” he joked. “It is too beautifully clear for their black deeds, so I guess your treasure will be safe,” he ended pleasantly.

“Oh, there’s little Nicky, Dads,” Barbara exclaimed, as Nicky did emerge from behind some boxes that were piled at the side of the fisherman’s cottage. “I must speak to him.”

Dr. Hale pulled his car up as short as his brakes allowed, and Nicky stood for a few moments as if waiting for them to reach him. Then, suddenly and without a cause which could be thought of by Barbara, he turned, ducked behind the boxes again and was as completely out of sight as if they had never seen him.

“I wonder what he did that for?” Babs exclaimed in astonishment.

“He didn’t want to see you, evidently,” replied Dr. Hale, throwing his car into gear again.

“Those youngsters can’t be depended upon,” said Miss Davis sagely. “They have no one to teach them anything so they pick up what is wrong.”

“Not Nicky,” defended Barbara. “He’s a fine little fellow.”

“Do you know him so well?” queried the woman, in surprise.

“Yes, I do,” stoutly declared Barbara. “And I know him to be—just splendid,” she finished, after an agitated pause.

“You see, Miss Davis,” said Dr. Hale politely, “my daughter is something of a philanthropist. She is always doing something for the neglected ones,” and he continued to talk in that strain for some minutes. But Barbara was not hearing a word he said.

She was wondering what was the matter with Nicky. Long before Miss Davis spoke of hearing a noise around the Community House, Barbara had caught a glimpse of Nicky. He was evidently trying to find out whom she was talking to, and he must have seen both her and Miss Davis with the little model craft, and also he must have seen where they hid it.

“But that couldn’t make any difference,” Barbara told herself, for she would even have trusted Nicky to do the hiding if he had been there, in the long old-fashioned room when she pried open the cupboard door.

“And so you and Miss Davis have a state secret,” the doctor interrupted her thoughts, as he pulled up to the porch of Miss Davis’ cottage.

“Yes,” said Barbara simply. She couldn’t seem to find her tongue, as Dora might have said.

“Don’t talk about secrets around here,” whispered Miss Davis, for her sister Tillie was just then coming to the door to see who might be arriving.

On the way home the doctor noticed Babs’ distraction.

“Anything go wrong with the show, girlie?” he asked gaily.

“Oh, no, why?” evaded Babs.

“You seem to have an awful lot on your mind for the first day,” replied her father.

“I have,” admitted Babs, still inattentive.

“I hope you are not going to have worries about the thing,” he said more decidedly, for none knew better than he that only worry could bring that blank look to his daughter’s face.

“Indeed I am not,” declared Barbara, now beginning to see what he meant. “We had a lot of fun. You should see some of the junk the ladies brought in and fought over.”

“Fought over?”

“Yes, where the stuff should be put, you know. Mrs. Brownell brought or had sent a really fine old table and it seemed as if everybody wanted her particular article put on that table.” This was quite a satisfactory speech for Babs under the circumstances.

“I can imagine what a fuss a lot of women would make over heirlooms,” the doctor commented. “What are we entering?”

“Why, what could we enter?” Babs repeated in surprise. “What heirlooms have we?”

“Take a look in the attic tomorrow,” her father replied laconically. “You may find something worth while.” Dr. Hale was being reflective. He seemed to know about the attic.

“All right Dads, I will,” Barbara agreed brightly. “It would be nice for us to have something to show. You have lived here longer than most of the new people,” she pointed out as they left the car in the garage and together walked up to their house.

“We have lived here for some time, Babs,” her father said rather solemnly. “But I just wonder if this place isn’t a little too big for just you and me?”

“Dads!”

“Oh, I don’t mean this year,” he hurried to reassure her, “but—well, don’t let’s think about it, Bobolink,” and he threw his arm fondly around her. “Think about your funny old ladies and their funny old home week,” he counselled, anxious to divert her attention.

But Babs couldn’t think about those things at all.