CHAPTER XV

THE WINGS

BEES belong to a class of insects known as Hymenoptera, which means with membranous wings; the wings of the bee are found to be composed of beautifully fine membranes. They are four in number, and, like the legs, are joined to the thorax. The front ones are called the anterior wings, and the back ones, which you will notice are smaller, are called the posterior wings, because they are behind the others. The membranes are strengthened by a kind of framework, just as a kite is strengthened by a framework of light sticks. The ribs of the framework are called “nervures,” and, as you will see from (a) Plate XI., there are divisions of transparent membrane in between; these are called cells. The nervures are hollow, and like our veins, they contain blood.

We have seen that the bee possesses two pairs of wings, and we may wonder why this should be so, when we know that one large pair is much more powerful for flying purposes than two small pairs. You have no doubt noticed that when a bee is at rest on a flower the wings are neatly folded over the back. Now if the bee had only one pair of large wings it would not be able to fold them so compactly—the wings would, in fact, stand out on each side of the body. We shall presently see that the bees, in the course of their duties, have to clean out the cells of the comb, and in order that they may do this it is necessary for them to be able to crawl right into the cell itself. The cells in which the young worker bees are raised are only 1⁄5th inch in diameter, and if the wings projected when in the folded position, the bee would not be able to enter the cell. The wings therefore have been divided, so that when folded they may lie one over the other on the bee’s back, and we find that the wings, when folded, take up only 1⁄6th inch of room. This leaves just sufficient space for their owner to enter a cell. You will notice that a blue-bottle fly has only one pair of large wings, for it does not need to fold them closely over its back, as it has no cells to clean.

Remembering what I have told you about the greater flying power of one pair of large wings, you might imagine that the division into two pairs which we have seen to be necessary would handicap the bee in flying. The difficulty is overcome by a most ingenious device, by which the bee, when flying, is able to fasten together the wings on each side, so as to form one pair of broad wings.

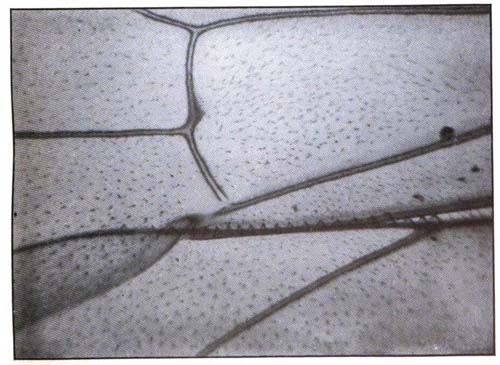

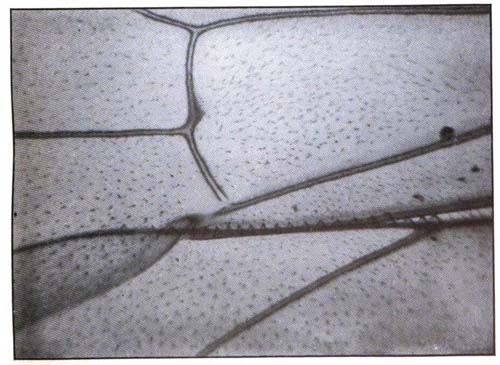

Let us now turn to (a) Plate XII., which shows part of the wings on one side of a bee’s body. Along the top edge of the lower wing there is a row of tiny hooks, and the lower edge of the upper wing is curled over, thus forming a kind of ridge. When the bee takes to flight the front wing is stretched out from over the back, and during this action it passes over the upper surface of the back wing. When the ridge reaches the hooks it catches upon them and is held fast. In this manner the two wings are locked together. (b) Plate XII. shows the wings hooked together ready for flying. When the bee comes to rest she folds her wings, and in doing this they are automatically separated, for the ridge slips away from the hooks that hold it.

PLATE XII

(a)

From a photo-micrograph by] [E. Hawks

Wing unhooked, showing Hooklets and Ridge

(b)

From a photo-micrograph by] [E. Hawks

Wing hooked, as in Flying

The number of hooks varies, and there are sometimes more on one side of the body than on the other. As a general rule it is found that a worker bee has from eighteen to twenty-three of them, the one shown in (a) Plate XII. having nineteen, as you will be able to count. The queen does very little flying, and so her wings are not large, in proportion to her size. Therefore she has not usually so many hooks, and sometimes they are found to number as few as thirteen. The drone has large and powerful wings, and his hooks vary between twenty-one and twenty-six in number.

Bees are able to move their wings very quickly, and you will agree with me in this when I tell you that it has been shown that the vibrations number at least 190 per second! The flight of the bee is greatly assisted by a number of air-sacs called tracheæ, contained in the thorax. These fill with air and make the body more buoyant, just as a lifeboat is made more buoyant by its air-chambers. When a bee has been at rest for a little time it cannot begin to fly straight away, for the air-sacs are empty. It therefore runs along the ground to get a start, as an aeroplane does, and by vibrating its wings fills the tracheæ.