CHAPTER XXII

THE CITY GATE

THE door of the hive, or the city gate as it may be called, always presents a busy spectacle, and Plate XVIII. is a photograph of one. Bees are constantly alighting on the board, coming so quickly that they appear to spring from nowhere. Other bees come out of the gates, and fly away quite as rapidly. Some even are in such a hurry that they do not wait to crawl on to the board, before taking to flight, but fly straight out of the door and away into the blue. Then, again, others do not seem to be in such a hurry, for they come out of the gates, and stand on the board brushing down their wings, seeming almost as though they were blinking in the bright light of the morning sun. These are the young bees, who are on their first expedition to gather honey; probably they have never been outside the dark hive before, and so they are unaccustomed to the strong light. They must take careful survey of the position and surroundings of the hive, so that they will be able to find it again when returning laden with honey. The bees which dart straight off from the hive door are the older workers, who have made many a journey to and fro, and so know very accurately the position of the hive.

PLATE XVIII

From a photograph by] [E. Hawks

The City Gate

All these are the foragers, or honey gatherers, and it is their business to visit hundreds of flowers over the country side, and to extract from them, by the aid of their wonderful tongues, the tiny drops of nectar. When their honey-sac is full, they return to the hive with all speed, and rushing inside, hand over the fruits of their labours to the house bees. You will be surprised to hear that a bee has to visit over 100 flowers before her honey-sac is filled, and we must not forget that this tiny sac when full holds only one-third of a drop. Now you will understand what a great number of bees are required, and how hard they have to work, in order to make 1 lb. of honey. Yet some hives give more than 200 lbs. of honey in a season! Just think of the vast amount of labour and the incessant toil required for this result. But the bees are always busy, and the proverb, “Go to the ant, thou sluggard,” might be quite well changed to “bee,” for I question whether the ant really works harder than the bee. From the time that the first ray of the morning sun strikes the dewy fields, until the sunset merges into misty twilight, all is bustle and hurry in the bee-city. So hard do the foragers work that instead of living three or four years like the queen, they often live only two or three weeks in the summer. In this short time their wings become quite worn away, and their poor little bodies are covered with wounds.

If we look carefully at the door of a hive on a warm summer’s day, we shall no doubt see some of these poor worn-out creatures. They can no longer take part in the great work of the hive, and so for a short time they come out into the sunshine and dodder about the alighting-board. Their mission in life being over, no doubt they will summon up all their remaining strength to fly away to some quiet spot where they will die, unheeded and unknown. Their last thought is to die somewhere away from the hive, so that their bodies may not interfere with the work of the city, and will not need others to carry them to a burial-place. How sad it is to think of these noble little workers, thousands upon thousands of which out of each hive willingly give up their lives for the great work of their race.

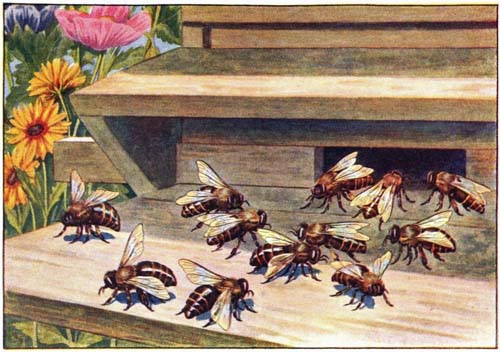

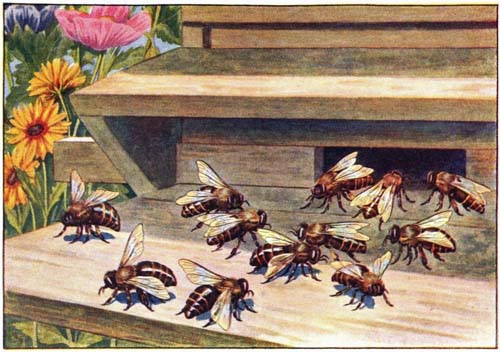

Besides the ever-busy foragers, there are other bees coming and going who do not appear to be in such a hurry. Each has two bright-coloured spots on her hind legs. These bees are the pollen gatherers, who collect the “bee-flour”; we might rightly call them the millers of the hive, and a picture of them is shown in Plate XIX.

Some of the bees at the city gates are employed in quite a different manner; they do not fly afar in search of honey or pollen, but stand still, with heads pointing to the hive door. They are using their wings so vigorously that we cannot see them, just as the propeller of an aeroplane is invisible, because it is turning so quickly. These are the ventilating bees, whose duty it is to keep the hive cool on hot days. The quick fanning of their wings draws out the heated air from the hive, and if we were able to peep inside the door we should see other bees also engaged in the same occupation. These, too, stand with their heads towards the hive door, but instead of fanning out the hot air, as the outside bees do, they draw a stream of pure, cool air into the hive. By this simple and wonderful arrangement the bees are able to regulate the temperature to a nicety, for if it grows too warm, they have only to set more fanners to work, to expel the hot air. The temperature of the hive is a very important matter, for should it become too high the young ones would be suffocated, whilst if it dropped too low they would be starved to death.

PLATE XIX

Pollen gathers at Hive Door

The fanning is very hard work, and so, if we watch, we see that as a bee grows tired her place is taken by a fresh worker, and so the ventilating is constantly kept up.

During the hot nights of summer, in the busiest time, the hive is thronged with workers who have come home from the fields to shelter from the dew and cold of the night. The city then becomes very crowded and hot, and a large army of bees must be kept at work ventilating. If, on such a night, we were to steal down to the hive with a lighted candle and place it a few inches from the door, the draught caused by the fanners would be quite strong enough to blow out the flame!