CHAPTER XL

BEE FLOWERS

UNTIL quite recent times it was not thought that the bees’ visits to flowers were for any other purpose than to gather food for themselves. It is now known, however, that their visits are really necessary to the flowers, and it is thought that flowers secrete nectar to attract them. Some kinds of flowers contain more nectar than others, and it is not always the largest which have the most. Small flowers are quite as interesting to study, if not more so, than large ones, and there is a great deal yet to be learned about even the tiniest flower. A primrose or a snowdrop possesses wonders which even the greatest scientists of the day cannot completely fathom. Lord Tennyson knew this when he wrote these beautiful lines:—

“Flower in the crannied wall,

I pluck you out of the crannies;

Hold you here, root and all, in my hand,

Little flower; but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is.”

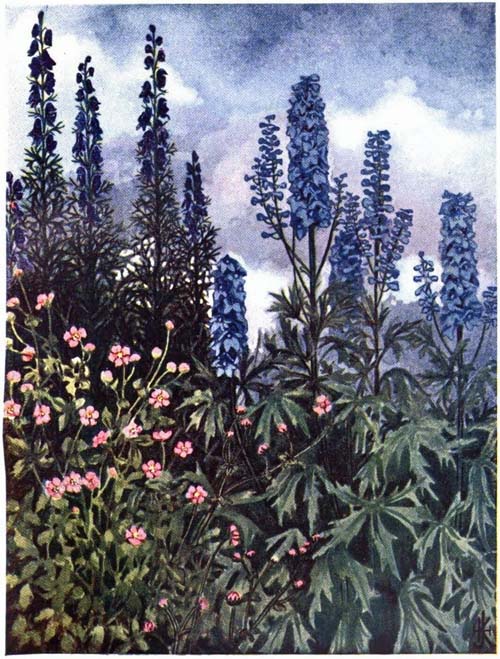

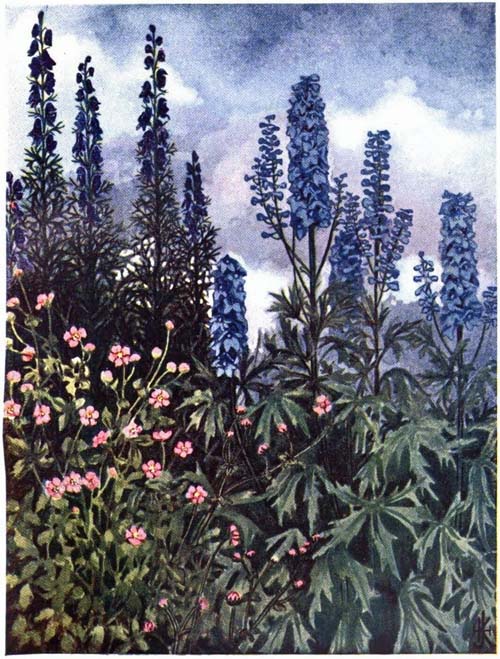

PLATE XXXV

Delphinium

Nature has so arranged things that all plants do not flower at the same time. Not only does this give us flowers nearly all the year round, but it allows the bees to work many months to gather in the stores for winter. Have you noticed that as soon as one kind of flower is over its place is taken by something else? Even though this arrangement does exist, it would be of but little value to the bees, unless the flowers were “honey” flowers—that is to say, the sort which secrete good supplies of nectar. Yet the bee-keeper knows that besides the ordinary flowers, those kinds which are useful to bees also follow one another from early spring to late autumn. There is thus a sort of calendar of honey flowers all the year round.

The bees will wake from their winter sleep as soon as the fine days of spring come, and it is then that the crocus is in flower. This flower is rich in pollen, which the bees commence to carry into the hive. In March there will be the daffodil and several other wild flowers, among which we may mention the dandelion and colts-foot. In April the blackthorn and palm will appear, whilst in May there will be a large number of wild flowers ready, including the broom, hawthorn, and foxglove. But June is the great bee month, for the fruit trees in the orchards are covered with blossom, and the clover makes the fields look white. Down in the south of England, too, there is the sainfoin, a flower which gives a large amount of nectar. In July the heather attracts those bees who are near the moors, while bramble flowers cover the hedges. In August there is still the heather, but the flowers begin to go, and the bees feel that winter is drawing near, and it is now that they make preparations for their long sleep. The last flower of the year is generally the ivy, which may be seen about October. This flower gives a little nectar, but, as the days are now cold and wet, the bees seldom leave the hives to gather it.

These are but a few of the best-known flowers, for there are hundreds of other kinds, and it would be interesting for you to make a calendar of your own. The two flowers from which the most nectar is obtained, are the white clover and the heather. Some flowers are of no use to the bee, although they store large quantities of nectar, for it is so placed that the bee cannot get to it, such as the red clover.

We have seen that bees can distinguish between colours, and it is even supposed that they have favourite colours, and that they prefer blue to any other. If you are able to watch a flower called delphinium, or larkspur (Plate XXXV.), which is light blue, and grows in parks and gardens, you will be surprised to notice what a number of bees it attracts, even though there may be many other kinds of flowers around.

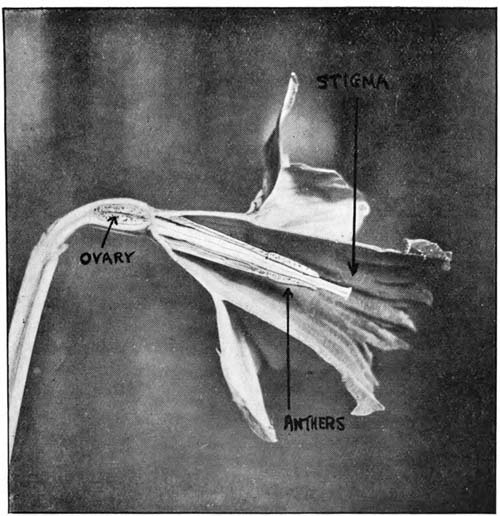

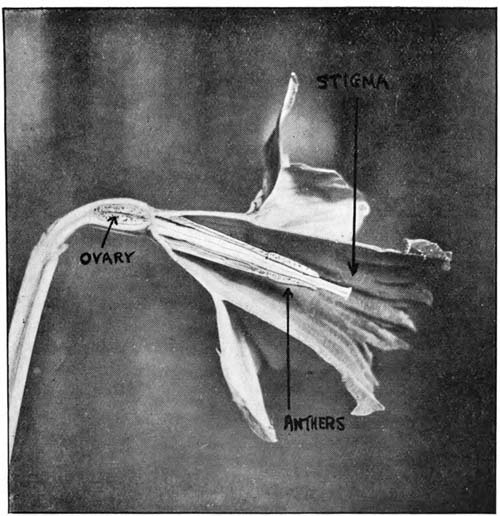

PLATE XXXVI

From a photograph by] [E. Hawks

Sectional View of Daffodil