CHAPTER XLII

BEES AND FLOWERS

FROM what you have read in the previous chapter you will see that for a flower to be fertilised the pollen must come from another plant. How, then, is this effected, for plants cannot walk to one another and ask for each other’s pollen? There are two ways in which Nature’s law can be fulfilled. The first is by the wind, for the pollen of some flowers, such as the willow-catkin, may be blown on to the stigmas of other catkins, and thus fertilise them. The stigmas of such plants are made branched and hairy, so as to allow of their more easily catching the flying pollen as it passes.

You will easily understand that it would not do for all plants to be wind-fertilised, for the chances of pollen grains alighting on stigmas would be very remote if that were the case. By far the greater number of plants, therefore, are fertilised in the second manner, which is by insects. The bees are the most useful of all, and we now see what service they render to plants, for when a little worker dips into a flower in search of nectar, her body becomes covered with pollen. It may be that the next flower she comes to is one in which the stigma is ripe, so that the bee, as she pushes her way in, rubs her pollen-covered body against it, and thus the flower is fertilised by pollen from another plant. When a bee is nectar-gathering, you will notice that she always keeps to one kind of plant on each journey, just as the pollen gatherers do. This arrangement fits in with Nature’s plan, for it is thus that pollen of the sweet-pea is carried to another sweet-pea, and not to a wallflower, and so with each kind of plant.

Many people think that the beautiful colours and scents of flowers exist only to delight man, but this is quite a wrong idea. For instance, just think of the gorgeous flowers which must grow and die in places where no human eye ever sees them. The real state of affairs is that man uses the flowers which already exist, and even if all men were to die, flowers would still continue to blossom.

The more we study flowers, the more clearly does it become evident that their rich colours, beautiful perfumes, and sweet nectar are really baits to entice insects to visit them. More than this, even the very marks in certain flowers point to where the insect will find the nectar, just as signposts on country roads direct us to the place we wish to find. Have you noticed that flowers which have gaudy colours, like the tulip, foxglove, or hollyhock, often have no smell, whilst insignificant flowers, as the mignonette, privet, or forget-me-not, give off beautiful scents? The first kind attract insects by their colour, but the second by their fragrance. Certain flowers have their nectaries at the base of the corolla, as the geranium; others have tiny little glands, or bags, on their petals, like the buttercup.

You will know that flowers open and close at different hours—in fact it is almost possible to tell the time by watching them. The little daisy is so called, for it is the “day’s eye,” and it closes at sunset; but the evening primrose is only just waking when the daisy is going to sleep. Who does not know that honeysuckle gives off its sweet fragrance in the evening-time? The reason for these facts is this. The daisy is open during the daytime, because it is visited and fertilised by insects who come only during the hours of daylight. The evening primrose is fertilised by moths which fly in the twilight and evening, and so it has no need to be awake by day. We can easily see, too, that the tube-like flower of the honeysuckle is far too long for the tongue of the little bee to reach its nectar, and the corolla is so narrow that she cannot creep down it. So the honeysuckle relies for fertilisation on moths, who have far longer tongues than bees, and it emits the lovely smell at evening-time to attract them.

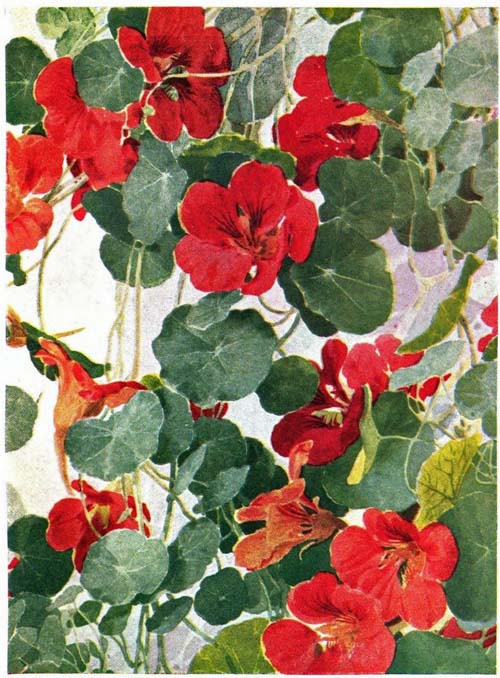

PLATE XXXVII

Nasturtiums