CHAPTER XLIV

HOW FLOWERS ARE FERTILISED

WE have now seen something of the contrivances of flowers to aid in their fertilisation, and in this chapter we shall consider the ingenious arrangement some flowers possess to assist their fertilisation.

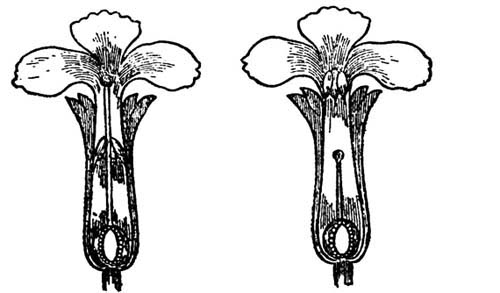

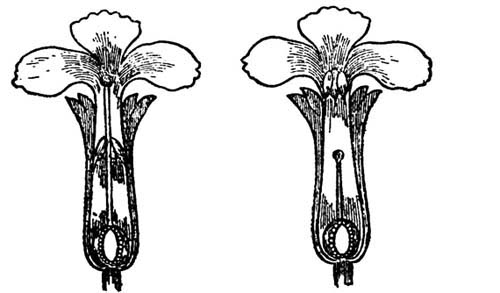

(a)(b)

Let us first look at the primrose. Have you ever noticed that there are two kinds of primrose flowers? From the outside perhaps they look very similar, but if you look closely, or better still, cut them open, you will find where they differ. Let us look at these sketches and we shall see that the one kind (a) has a long style, which reaches nearly to the top of the corolla. The other kind (b) has quite a short style, so that instead of the stigma, or knob, being at the top of the corolla, it is really half-way down. We notice, too, that the anthers, or pollen bags, in the first kind (a) are placed half-way down the corolla, and in the other flower (b) they are at the top. We might think that Nature had made some mistake here, for it seems that if the pollen bags belonging to flower (a) were placed in flower (b), or vice versa, things would be more natural.

Let us suppose that a bee visits flower (a) and dips her tongue down the corolla to collect the nectar. Half-way down the flower the tongue has to pass the pollen bags, and in doing so gets dusted over with pollen grains. The bee, having collected the nectar, flies to another plant, which we will suppose bears flowers of the other kind. She dips down her tongue, which touches the stigma just at the place where it had been covered with pollen by the first flower. By this means, therefore, the flower (b) is fertilised. But, you will ask, what about flower (a)? While the fertilisation of flower (b) has been going on, the pollen bags of (b) at the top of the corolla have dusted the root of the bee’s tongue, so that when she goes to a flower of the (a) type, the pollen dust at the root of her tongue touches the stigma, and the flower is thus fertilised.

What a wonderful arrangement this is, for you will see that it is almost impossible for the flowers of one primrose plant to fertilise each other; the pollen must come from the flowers of a different plant.

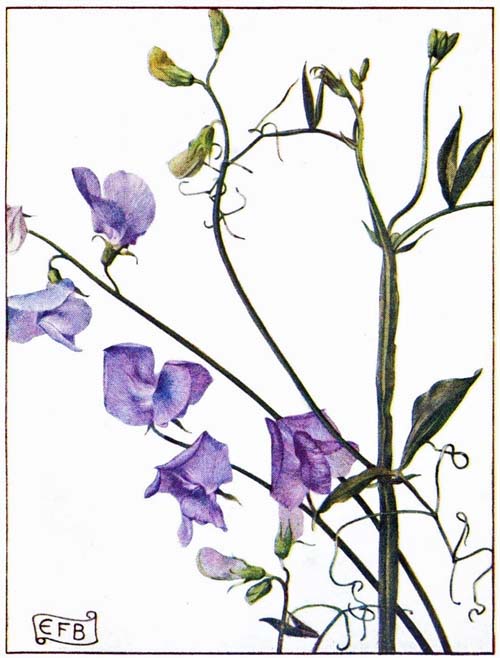

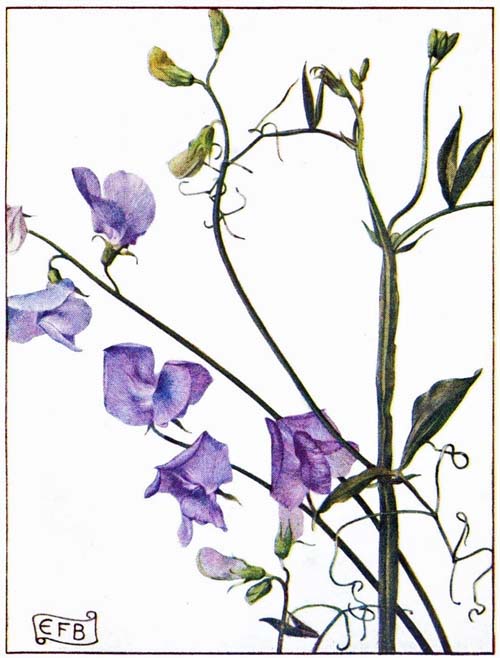

Some flowers, if not fertilised by insects, have the power to fertilise themselves, and to this class belongs the sweet-pea (Plate XXXVIII.). This flower belongs to the papilionaceous (butterfly) tribe, and when a bee alights on the flower its weight presses down the underpart. While the bee is taking the nectar, the pollen bags rise and touch her on the underside of the thorax. Then she goes on to another flower whose stigma is ripe. This time the stigma rises and touches the same part of the bee’s body, and in this manner the flower is fertilised.

PLATE XXXVIII

Sweet Pea

Some plants have wonderful arrangements for transferring their pollen to other flowers, some of which are so peculiar and clever that we might think they had been designed by some crafty scientist. One of these is called the salvia, and it belongs to the same family as the dead nettle. The anthers are mounted like a see-saw, and when the bee makes its way into the flower it pushes one end of the see-saw up. This causes the other end, on which the pollen bags are situated, to come down thump on to the bee’s back. The pollen is thus scattered there, and the bee also receives what may be called a pat on the back! As the salvia flower grows old its pollen bags shrivel up, but at this time the stigma is ripe. It grows longer and longer, and bends over till it is like a letter J turned upside down:  After a bee has visited some young flowers and had her back dusted with pollen, she will, without doubt, visit some of the older ones too, and it is quite easy to understand that when she enters these she rubs her back against the overhanging stigma, and the pollen adheres to it.

After a bee has visited some young flowers and had her back dusted with pollen, she will, without doubt, visit some of the older ones too, and it is quite easy to understand that when she enters these she rubs her back against the overhanging stigma, and the pollen adheres to it.

Another interesting plant is the violet, the nectar of which is stored at the end of the long spur, which you will have noticed. The pollen bags fit closely round the stigma, and so when pollen drops from them it does not fall out of the flower, for its passage is blocked by the tight-fitting pollen bags. When the bee comes, she has to push her tongue right up the spur, and in doing this she forces it past the pollen bags. This causes the pollen to fall out on to her head, and so it is carried to the next flower.