Billy Jr. Learns Something about Cowboys and Indians.

ONE morning three months later Billy Jr. appeared, tired, cold, and hungry, in front of a ranchman’s door; and was first seen by the Chinese cook, who opened the kitchen door of the long adobe house to see what the weather was like. There was Billy by the well, trying to get a drink out of the almost empty bucket on the well-curb.

Billy’s first thought when he saw the Chinaman was to run away, for he had been so illy treated lately—shot at, stoned, and half-starved—that he had lost some of his assurance and confidence in people and preferred to look them well over before he got too near. But the Chinaman appeared so inoffensive that he stood his ground and stared back when the man rubbed his eyes to see if it really were a large, live billy-goat by the well; his first thought being that he had not quite got over his opium pipe of last night. But when Billy Jr. bleated a good-morning to him, he came out of his stupor, walked to the well, and drew a bucket of water for the tired, thirsty beast.

From that day Billy was a fast friend of the Chinaman. Never in his life had anything tasted so good and refreshing as that cool drink of water after his long, dusty trip across the plains and mesas.

For a day and a night Billy Jr. had followed a wagon trail without passing a human being or habitation, and when he saw this ranchhouse it was indeed a welcome sight. He was tired, lonesome, hungry, and discouraged, and he knew that he must go back to the little town by the railroad, the last settlement he had met with, if he did not soon find a house and some living thing, man or beast, he could not endure the dreary solitude another day.

He preferred the town to this, even if the boys did tie tin cans to his tail, the women chase him with broomsticks or throw hot water on him when he tried to steal a meal from their kitchens, and the cow-boys aim at him to see how near they could come without actually shooting him. Once, when he stopped to get a drink of water from a trough standing outside of a saloon, the cow-boys caught him and forced him to drink some beer, which made him feel dizzy and as if the sidewalk were flying up and going to hit him in the face. And, oh my! what a splitting headache he had all the next day! It made him wonder and wonder how people could drink such nasty, bitter stuff when they could have pure, clear water instead, and he thought if they had to pay five dollars a bottle for water, perhaps they would crave it.

After these experiences, do you wonder that Billy was glad to find a friend in the Chinaman?

When the potatoes were peeled for breakfast the next morning, the skins were given to Billy, and they tasted as good to him, after his long fast, as fresh turnips did when he was living in plenty.

Just as the sun lighted the tops of the mountains, the Chinaman rang a large bell that hung on a high pole near the well, to call the cow-boys to breakfast, and as its peals rang out on the morning air it was answered by the barking of what seemed to be dozens of coyotes, although, in reality, there was perhaps not half that number; a peculiarity of their bark being that it seems to double itself and to sound as if coming from twice as many throats as it really does. Billy did not like to hear the coyotes, for their dismal cries made him feel both lonesome and homesick.

Immediately after breakfast the cow-boys rode off to look after the cattle and as soon as Billy saw them depart he gave a sigh of relief, for when they were around they were always plaguing him and throwing lassos or cracking their whips at him.

“Now, while the Chinaman is busy with his dishes and the cow-boys are away, is my time to explore the premises and find out what things look like around here,” thought Billy and, seeing an open door, he walked through and found himself in a long, low room barren of carpet or furniture, unless two tiers of bunks, a wooden chair or two, a washstand with a tin basin on it, and a cracked looking-glass, could be called furniture.

This room was in great disorder. Boots were lying around everywhere; some in the bunks, others sticking out from under them, and still others strewn about in general confusion all over the floor; and where there were no boots there were clay and corn-cob pipes with half-empty tobacco bags beneath them. None of these things surprised Billy, but what did puzzle him was that between the windows there were a lot of holes in the walls which were filled with old rags loosely poked in, while guns of all sizes and descriptions hung on the walls or were stacked in the corners of the room.

“This looks like a fort,” thought Billy, “but I fail to see who there is to fight around here.” But, even as he thought this, he remembered that Indians lived in this territory, and cold chills ran down his spine, for although he was only a goat, he had often heard of the unparalleled cruelty of the Apache Indian dwelling in this part of the country and he at once realized why this house had been built with holes in its walls and why all the guns were there. In case of a siege, the cow-boys barricaded the windows and doors and stuck the barrels of their guns into these holes, and then they were prepared to resist an attack and to defend themselves.

Besides the room in which Billy stood, the house contained a sitting-room, dining-room, kitchen, and a small room that was kept shut up except when occupied by the owner during his yearly visits to the ranch.

When Billy had reached this point in his explorations, he heard the Chinaman calling, “Bee-lee, Bee-lee, Bee-lee.”

“I suppose that means me, so since he makes my name sound so much like Bee, I will carry out the notion and make a bee-line for him,” said Billy.

“Where-ee you been, Bee-lee?” said the Chinaman when he saw Billy running toward him. “Come-ee long-ee in a here-ee; I have-ee something good-ee for-ee you-ee,” and he gave Billy a piece of Johnnie-cake that had been scorched in the baking-and which he did not want the ranchman to see because of the wasted meal.

While Billy Jr. was eating, the Chinaman threw himself down upon a wooden bench in the corner of the room, took two or three whiffs from his opium pipe and was soon fast asleep, dreaming doubtless of his almond-eyed sweetheart in the Orient. When Billy saw the pipe fall from his hand, he took first a smell and then a taste of the powder that had spilled out of it upon the floor; and soon he felt the most delightful, drowsy sensation stealing over him, and he, too, curled himself up by the bench near the Chinaman and was soon dreaming that he was back in the old home meadow with his father, mother, and Day; but the meadow he dreamed of was covered with sweeter clover blossoms than any goat ever ate and the breeze that fanned his face was laden with sweeter perfume than mortals ever breathed.

Billy was rudely awakened from this beautiful vision by a vigorous kick and on recovering his bewildered senses, he found the room filled with excited cow-boys all talking at once. From their conversation he soon learned that the Indians were out on the warpath and were even now within sight of the house.

With wondering eyes Billy watched the boys board up the windows, barricade the doors, and stick the gun-barrels into the holes in the wall. Presently, he was driven into the sitting-room and to his surprise he found that five of the cow-boys’ ponies had also been driven in here for safety, as the boys well knew that the Indians would steal them if left outside. He had no sooner entered this room than he heard a loud bang, and a bullet flattened itself against the doorjamb just as the Chinaman ran in carrying a bucket of water from the well; for during a siege, water is a necessity for both man and beast, and while the boys had been boarding up the windows from the inside, the Chinaman had been busy filling an old barrel with water from the well.

“The red devils are upon us,” he heard a cow-boy say, and then the door was slammed shut and he was alone with the ponies. While the bullets sped thick and fast, and showers of arrows fell, all of which were answered by the cow-boys’ bullets as they tried to pick off the Indians skulking around the house, the ponies told Billy when and how the raid began.

An old roan pony that had been on the ranch for years said, “When we went out this morning to round up and count the cattle, Jim Dowsen, the man who rides me, said, ‘Something has happened during the night, for the cattle are frightened and restless,’ and when we got near them we saw at a glance what was the matter.” And he proceeded to tell Billy about the last raid of the redskins.

The Indians had ridden into the herd during the night, had stolen fifty head of the company’s best cattle, and had ham-strung about fifteen more out of wanton cruelty, because the savage nature delights in torture. When Jim saw what had been done he was furious and he rode off like the wind to find the herder who had been with the cattle. After riding around the whole herd twice without discovering any trace of him, he at last found him lying face downward on the ground, his body without arms, his head minus its scalp. After mutilating him, the savages had left him for the wolves and vultures to devour, and then satisfied with their fiendish work had stolen his pony and ridden away. Billy discovered that the Apache Indians were the most cruel and fiendish of all the tribes living in the territories.

During all this time the fury of the savages had increased.

Before leaving the ranch, the redskins intended finishing their work of destruction. They wanted pale faces. They wanted scalps. But most of all, they wanted fire-water (the Indian name for whisky). And so the attack lasted for three days or more. Provisions were getting low within the cabin, the fuel to cook the meals with was gone, and the horses were neighing for fodder, as they had been fed only potatoes and cabbage once a day, and then as a last resort, straw out of the mattresses; and still the Indians skulked outside and waited for the little band of men in the house either to surrender or to starve.

The third night of the siege the boys began to lose courage. Constant watching, loss of sleep, little to drink and less to eat had nearly worn them out, while their enemies seemed to be in perfect condition and acted as though satisfied to camp outside their door for the rest of their natural lives.

At last, one of the cow-boys named Henry Staples said, “I have it, boys! I know just how we can get out of here; save our scalps and, what is better still, kill every one of those fiends sitting outside grimly waiting to see our finish.”

“Don’t buoy us up with a fairy tale like that, Henry,” they all said, “for it is too good to be true.”

“Listen and hear my plan,” he replied. “You remember that can of rat-poison we bought to kill rats with when in town the last time?”

“Yes,” they answered.

“Well, let us take that rat-poison and put it in a keg of fire-water; next, run up a flag of truce, then set the keg with seven or eight cups outside. Thinking we are offering it in the place of a peace pipe, the Indians will not hesitate to come and drink. They are used to poor fire-water and so will be less likely to detect the poison and will drink cup after cup until they are stupified, and in the end the poison will kill them as surely as it would kill the rats. These Indians are not any better than rats and should be treated as such. Have they not tortured and killed hundreds of people?”

“You are right, Henry; we can at least try your plan. It seems the only feasible way out of our plight, and it can but fail.” So they blew a horn to attract the attention of the Indians and then hoisted a flag of truce on the flag-pole at the side of the house where the United States flag usually floated; and while the Indians were watching it, the cow-boys set the fire-water outside with the cups on top of the keg; then, through the peep-holes where the guns had been, they watched the Indians confer together about coming forward to get a taste of the much coveted fire-water.

Presently a big buck, evidently the chief of the tribe, walked boldly forward and took a drink. He smacked his lips and then drew another cupful, which he swallowed at one gulp. Upon seeing this, the other braves ran up to get their share, for they did not know how much or how little the keg might contain. When they found that it was full, they commenced to dance around in high glee and they drank again and again as if they could not get enough.

“I should like to shoot every one of them as they now stand,” said Henry.

“No, don’t,” said the others. “Save your ammunition for live Indians. These will soon be dead.”

The chief, who had taken the first drink, was now feeling the effect of the potion and was becoming quarrelsome. He soon began to fight with another big Indian and this led to the rest taking sides with one or the other, and soon all were engaged in a grand melee, flourishing their weapons in a most reckless and dangerous manner, regardless of consequences, because the fire-water had gone to their heads. Presently a young buck, half-crazed under the combined influence of the fire-water and the poison, started for the door of the house and tried to batter it down, forgetting all about the flag of truce, and calling upon the other Indians to follow him and scalp the pale faces, but, even as their arms were upraised to strike the door, they were seized with cramps and violent pains. The poison had conquered at last and soon all were lying around in every possible shape, twisting and writhing in their death struggles.

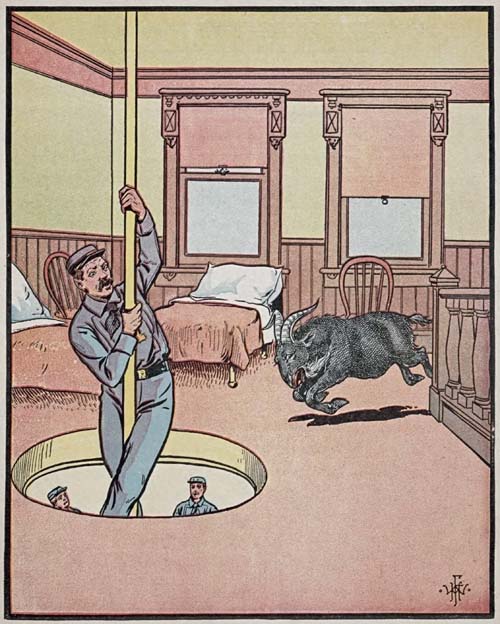

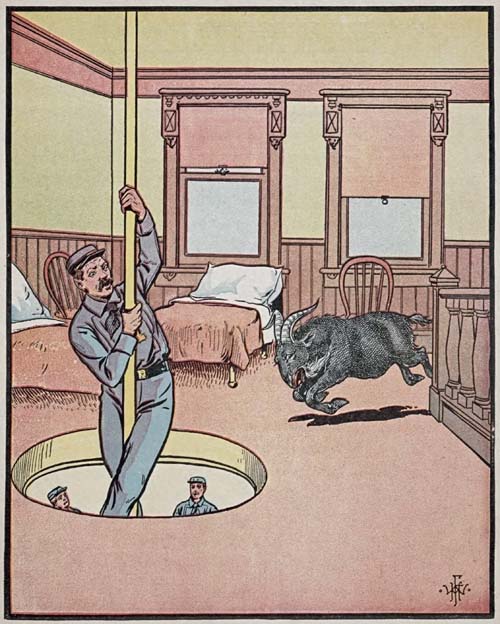

THE MAN MADE A GRAB FOR THE GREASED POLE AND DOWN HE WENT.

In less than an hour every Indian lay motionless and the cow-boys went out to take possession of their arms and ponies. Suddenly Billy saw an Indian, supposed to be dead, stealthily rise and creep after one of the boys who was bending over a dead brave unstrapping his cartridge belt. For a second he saw a knife glisten in the sunlight and he knew that in another instant it would be buried in the unsuspecting boy’s back. With Billy, to see was to act, so without hesitation he rushed upon the treacherous Indian and tossed him aside as if he had been a paper ball. The knife dropped from his hand, for he had been killed instantly. One of Billy’s sharp horns had pierced his heart. All the cow-boy said, when he realized what Billy had done, was, “Billy, you have saved my life and for this you shall have a collar of gold, with your name and a record of your brave act engraved upon it.” The cow-boy kept his promise, so ever after Billy wore his collar of gold.

A few days after the siege, Billy felt that he had seen enough of ranch life and life on the plains, so he decided to return to town and from there go to some large city as fast as his legs would carry him. “For, if I stay here,” he mused, “other Indians may come to avenge those who have been poisoned. They may take a fancy to my horns to decorate one of their wigwams and may cut my head off, and then where would I be? Who knows but what they may come this very night? Anyhow I have seen enough of wild western life and I shall leave this country right now. There is no time like the present,” and with this soliloquy he started on a dead run for town by the same way he had come and he never stopped to say good-bye even to the Chinaman.