CHAPTER IX

ALONE IN AN OCEAN STORM

oor Billy! Once more he had lost his mother! He looked for the ship to turn round and send out a boat as it had done when Hans fell overboard, but it did nothing of the sort. Instead, it steamed straight ahead. In the excitement nobody had noticed that Billy had been thrown into the water.

oor Billy! Once more he had lost his mother! He looked for the ship to turn round and send out a boat as it had done when Hans fell overboard, but it did nothing of the sort. Instead, it steamed straight ahead. In the excitement nobody had noticed that Billy had been thrown into the water.

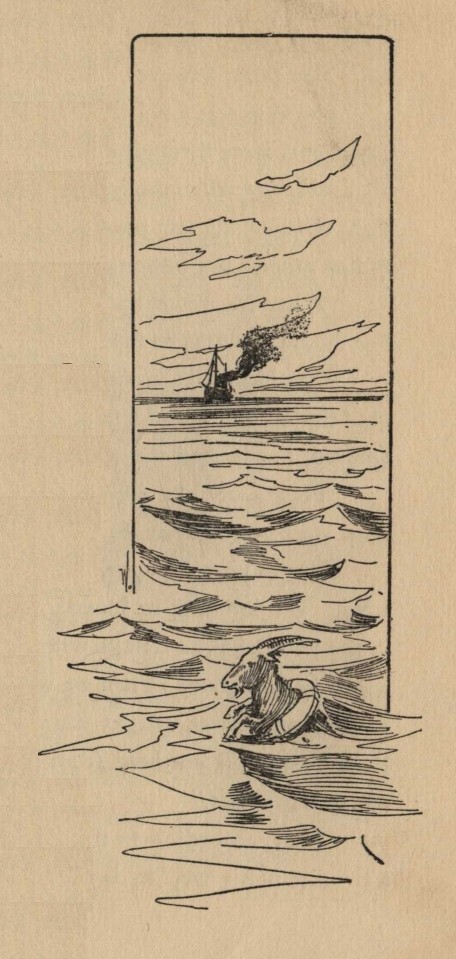

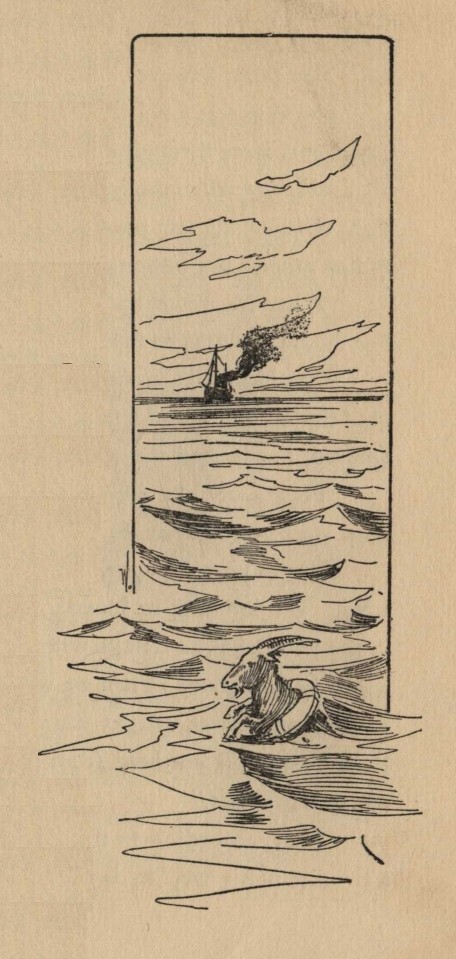

The cook got a life preserver and threw it over after Billy, thinking it a good joke, then the cook went below and Hans stood at the stern railing shaking his fist at the poor goat. Billy swam as long and as hard after the boat as he could, but it was no use; he could not begin to keep up with its great speed. Presently, however, he came to where the life preserver floated. It was a big circular one and Billy put his front paws upon it. His weight made it tip on edge and Billy was surprised and delighted to find that it held him up in the water, making the work of swimming much easier. In trying to get his legs further into it he slipped once or twice, but finally in his struggles his head and horns went through it, and, after swimming and wriggling a little bit, he got his front shoulders through and there it clung round him, holding him up splendidly. It was too small to pass backwards over his body, and it could not get off over his head on account of Billy's horns.

It was a lucky thing for Billy that this happened, for that night a terrific storm came up. The wind shrieked and howled, the lightnings glared, the thunders rolled, and great foam-capped waves, some of them nearly as high as a house, broke over Billy, one after another, nearly drowning him and sometimes almost crushing him by their weight.

In all his life Billy had never passed such a terrific night as this, but through it all the big life preserver held him up and carried him safely through. Many times there seemed to come a lull in the storm and Billy began to breathe easier, thinking that he would get a little rest, but the storm would break out again with new fury each time, until, when morning came, the poor goat was battered and bruised and nearly dead. With the dawn, however, the storm calmed down. The skies began to clear, the waves grew smaller, and the wind, shifting by-and-by to the opposite direction from that in which it had been blowing all night, beat back the waves and smoothed them down until by ten o'clock the ocean was quiet, only ruffled by gentle swells over which Billy and his life preserver bobbed in comfort, although he was very tired and beginning to get hungry.

Ever since the sky had cleared he had seen smoke away off where sea and sky seemed to join. Billy knew what smoke meant. Wherever there was smoke there were people, and wherever there were people there was food, so he started toward it, swimming a little bit and resting a long while between times. The smoke grew blacker and presently he saw a little speck under the smoke. It grew larger and larger, and by-and-by he was able to make out that it was a big ship coming in his direction. Poor Billy swam harder than ever then, and fortunately for him the ship was coming almost straight toward him. Still more fortunately, the captain, sweeping the sea with his glass, made out the life preserver holding up something white, and immediately thought it must be a woman in a white dress. He altered the direction of the ship slightly so that it came nearer to Billy, and had ordered a boat to be lowered before he made out that it was only a goat, otherwise he might have passed on by. The boat, however, was already lowered, so he let it go.

The ship was coming almost straight toward him.

The ship was a big passenger steamer, and by this time scores of passengers were thronging to the rails to see what the excitement was all about, and when the boat was drawn up, Billy, a comical looking sight with his big life preserver around him, was placed on the deck. A boy among the passengers at once ran forward with a shout.

"Why, it's my Billy goat!" he cried. "Papa, come and look! See the singe marks on his back?"

Billy "baahed" joyfully. He rather liked Frank and was very glad that he had found a friend. The captain himself, interested and amused, had joined the crowd by this time.

"Your goat?" he asked Frank, in amazement. "Do you always keep your goats out at sea in life preservers?"

"Not always," laughed Frank. "In fact, this is the only goat I have. We lost him in Havre. The last I saw of him he was tied to the back of our carriage with a rope. When we got down to the wharf he was gone. Then we went down to Cherbourg, where papa had some business, caught your ship the next day and here we are. How Billy ever got here from Havre, I don't know, but here he is and he's my goat."

"Well, according to the law of the sea," said the captain with a twinkle in his eye, "he is salvage now and belongs to the men there who picked him up. Of course I have a share in the salvage too, but I'll take a cigar for mine."

Mr. Brown, laughing, gave him the cigar and then gave the sailors some money, and Billy was taken below to a large, white, clean room where some fine blooded horses were hitched in roomy stalls. Here he was given a big bowl of warm milk and a bed of clean straw, both of which he was very glad to get. As soon as he had drunk the bowl of milk, he felt so good and warm that he lay down and went sound asleep.

When Billy woke up he saw something that made him gasp with surprise, and at first he thought he must be dreaming. Right beside him, sleeping peacefully, an empty bowl that had contained milk just in front of it, lay another goat. It was his mother! Billy was so overjoyed that he did not know what to do. He licked her face gently and when she opened her eyes he capered around till the horses in the stalls near by thought that he must have gone crazy. Billy's mother was no less happy and when they had calmed down Billy told her how Hans Zug had thrown him overboard, how he had suffered through the storm and how the ship had picked him up.

"You were lucky, I guess, that he threw you over," said his mother. "We got into that same terrible storm and our ship struck upon the rocks and broke to pieces. I do not know what became of the other goats or of Hans Zug. Of course all the circus animals in the cages went down. I was swimming about in the water when some sailors in a boat grabbed me and took me with them. They said that they had not had time to get provisions and that they might have to eat me. I would have jumped overboard when I heard this but they had already forced me under one of the seats in such a way that I could not scramble out. The storm was still upon us and the waves spun us around like a top, and two or three times we thought we were gone. By morning, however, the storm calmed down and we were safe, although some of the men had been swept overboard by the big waves that broke over us. All day long we drifted about. One of the men had brought along a box of crackers and another one had got some dried beef. A keg of water was already in the boat so that there was nearly enough for everybody for breakfast, and when the noonday meal came, one of the men wanted to kill me, but the others would not let him. They wanted to save me, they said, until the next day. It was nearly dusk when this ship saw us and stopped to take us on board. If this ship had missed us I suppose that to-night would have been my last."

Billy shuddered.

"Well," said he, "at any rate we are together again, and this time I suppose that we will stay together. If you are rested enough come on and let us look around the ship."

First the two goats trotted side by side past the big clean stalls of the horses and all around the room they were in, then they made their way to the stairway that led up to the deck. They were about to climb this when Billy spied the open door of a little closet, scarcely large enough to put his head in. Full of curiosity, he went up to it and stuck his nose inside.

"Oh, come here, mother!" he suddenly cried. "Here is a rope with a very strange taste. I had some of it in a big hotel in Bern and I did not care for it very much, but it has such a queer taste that you must eat some of it."

The rope Billy meant was not exactly like the ones he had chewed in Bern, for those were single big wires with a covering to keep them from touching. This rope in the little closet was not a solid one but was a big bundle of tiny wires, each one covered with a queer tasting sheath. The wires ran from the pilot's room and the captain's room to the engineer's room and to the other working rooms of the ship, and, by the use of little push buttons were intended to direct the movements of the mighty floating palace.

"Why, this is quite a treat," said Billy's mother, taking a big bundle of the wires in her mouth. Another little closet just like this one stood alongside of it and Billy saw that the door of this was also slightly ajar. He pushed it open with his nose, and inside he found another bundle of wires. These ran from the passengers' cabins to the steward's cabin, and the electrician had just been fixing them, carelessly leaving the doors unfastened.

"Why, here's another bundle! I'll try some of them myself," remarked Billy, so both the goats got to work at once.

Billy's mother had only chewed at her rope of wires a little while when the coverings began to come off and the wires to touch. Instantly things began to happen. The first wires that touched gave the engineer a signal to stop and instantly the mighty ship began to slow up. Within a short time it had come almost to a standstill and the first mate, up in the pilot room, immediately took down his telephone and called up the engineer.

"What's the matter?" he asked.

"Nothing, sir," said the engineer. "You gave the signal to stop and we stopped."

"I did no such thing," said the mate. "At any rate, start up again and we'll investigate."

Just then came another signal, and with a great jangling of bells the big engines began to turn and the ship wheeled square around. There was another jangling of bells, and, shaking with the force of the mighty engines, the ship began to pick up speed, headed straight back for France. Again the first mate called up the engineer.

"What are you doing?" he asked. "Are you crazy? Why have you tacked about?"

"Had orders, sir," said the engineer.

"You lay her northwest by north at once. Put the second engineer in charge and report to me immediately."

"Aye, aye, sir," said the engineer and started up to present himself to the first mate.

The ship was swung back on her proper course and had gone straight a little way, when all at once the whistles began to blow and bells to ring, and with this the captain came running up to the pilot room. The first mate already had his telephone off the hook and was screaming down to the engineer.

"What are you doing, sir?" he demanded. "I thought I told you to report to me at once!"

"This is the second engineer, sir," repeated the voice. "The chief engineer has just gone up to report to you, sir."

"Well, why did you blow a landing whistle out here in mid-ocean? Can't you obey orders? Are you crazy, too? Are you all crazy?"

"I had the signal and obeyed orders, sir," said the second engineer.

By that time the captain came bursting into the pilot room, while Billy Mischief and his mother were chewing wires.

"Are you a plum idiot?" demanded the captain. "Can't you be left in charge of this ship? Have you been drinking? First you stopped the ship, then you put back for France, then you turn again, and now you blow a landing whistle."

At that moment the fog horn began to sound, although the sea was almost as bright as day with a round moon shining overhead and the stars studded thick in the sky.

The captain himself grabbed the telephone.

"I want to know who's doing all this!" he demanded. "Who's in charge there?"

"I am, sir; the second engineer," answered the voice.

"Put your assistant in charge and report to me in the pilot room at once."

Just then the chief engineer came in.

"What does all this mean?" roared the captain.

"I don't know, sir," said the engineer. "I got signals to stop, then to put about, then to come back on the course, all of which I did."

"I don't want you to attempt to put this on to me," said the mate. "I haven't touched a button for an hour. There has been no necessity. We have been going straight on our course.”

"SHAKE HANDS," SAID BOBBY.

All this while the steward had been going nearly crazy. The bells were ringing from every cabin on the ship, and the waiters were running about the place like mad. First one bell, then another would ring, and always when the waiters went to those cabins they were told that nothing was wanted and were abused for waking people up. That part of it was Billy Mischief's work and he did as much to put the ship in an uproar as had his mother. The sound of the fog horn and the stopping and starting of the ship, the whistling and the clanging of the bells, kept everybody awake that had been awakened by the waiters, and hastily throwing on clothing, the passengers began to hurry out on to the decks to find out what was the matter.

The steward came hunting the captain, right after the second engineer.

"This ship is bewitched," he cried, wringing his hands, and he told the captain of all the trouble he was having with false alarms.

Everybody looked at everybody else as if they thought that the others had all better be in the asylum, and it was just at that moment that Billy Mischief, down in the hold, turned to his mother and said:

"Oh, come on! I don't like this stuff very well, anyhow," and leaving the little closets to themselves, they trotted innocently upstairs not knowing all the trouble they had made.

oor Billy! Once more he had lost his mother! He looked for the ship to turn round and send out a boat as it had done when Hans fell overboard, but it did nothing of the sort. Instead, it steamed straight ahead. In the excitement nobody had noticed that Billy had been thrown into the water.

oor Billy! Once more he had lost his mother! He looked for the ship to turn round and send out a boat as it had done when Hans fell overboard, but it did nothing of the sort. Instead, it steamed straight ahead. In the excitement nobody had noticed that Billy had been thrown into the water.