CHAPTER THREE

I

With all his outward candor the Governor had, Archie found, reserves that were quite unaccountable. He let fall allusions to his past in the most natural fashion, with an incidental air that added to their plausibility, without ever tearing aside the veil that concealed his origin or the manner of his fall, if, indeed, a man who so jubilantly boasted of his crimes and seemed to find an infinite satisfaction and delight in his turpitude, could be said to have fallen. Having mentioned Brattleboro as the point at which they were to foregather with Red Leary, the Governor did not refer to the matter again, but chose routes and made detours without explanation.

As a matter of fact they swung round Brattleboro and saw only the faint blue of its smoke from the western side. It was on the second afternoon out of Cornford that the Governor suddenly bade Archie, whom he encouraged to drive much of the time, pause at a gate.

"We linger here, son. May I suggest that you take your cue from me? Bill Walker is an honest dairyman to all intents and purposes, but really an old crook who got tired of dodging sheriffs and bloodhounds and bought this farm. A sober, industrious family man, you will find him, with a wife and one daughter. This is one of the best stations of the underground railroad; safe as a mother's arms, and you will never believe you're not the favored guest of a week-end party. Walker's an old chum of Leary's. They used to cut up in the most reprehensible fashion out West in old times. You've probably wondered what becomes of old crooks. Walker is of course an unusual specimen, for he knew when the quitting was good, and having salted away a nice little fortune accumulated in express hold-ups, he dwells here in peace and passes the hat at the meeting house every Sunday. You may be dead sure that only the aristocracy of our profession have the entrée at Walker's. His herd on the hillside yonder makes a pretty picture of tranquillity. The house is an old timer, but he's made a comfortable place of it, and the wife and daughter set a wonderful table. Here's the old boy now."

A gray-bearded man with a pronounced stoop, clad in faded blue overalls, was waiting for them at the barn.

"Just run the machine right in," he called.

The car disposed of, the Governor introduced Archie as one of his dearest friends, and the hand Archie clasped was undeniably roughened by toil. Walker mumbled a "glad-to-see-ye," and lazily looked him over.

"Always glad to meet any friend of Mr. Saulsbury's," he drawled with a mournful twang. "We've got plenty o' bread and milk for strangers. Somebody's spread the idea we run a hotel here and we're pestered a good deal with folks that want to stop for a meal. We take care o' 'em mostly. The wife and little gal sort o' like havin' folks stop; takes away the lonesomeness."

There was nothing in his speech or manner to suggest that he had ever been a road agent. He assisted them in carrying their traps to the house, talking farmer fashion of the weather, crops and the state of the roads. The house was connected with the barn in the usual New England style. In the kitchen a girl sang cheerily and hearing her the Governor paused and struck an attitude.

"O divinity! O Deity of the Green Hills! O Lovely Daughter of the Stars! O Iphigenia!"

The girl appeared at a window, rested her bare arms on the sill and smilingly saluted them with a cheery "Hello there!"

"Look upon that picture!" exclaimed the Governor, seizing Archie's arm. "In old times upon Olympus she was cup-bearer to the gods, but here she is Sally Walker, and never so charming as when she sits enthroned upon the milking stool. Miss Walker, my old friend, Mr. Comly, or Achilles, as you will!"

A very pretty picture Miss Walker made in the kitchen window, a vivid portrait that immediately enhanced Archie's pleasurable sensations in finding a haven that promised rest and security. Her black hair was swept back smoothly from her forehead and there was the glow of perfect health in her rounded cheeks. Archie noted her dimples and the white even teeth that made something noteworthy and memorable of her smile.

"Well, Mr. Saulsbury, I've read all those books you sent me, and the candy was the finest I ever tasted."

"She remembers! Amid all her domestic cares, she remembers! My dear lad, the girl is one in a million!"

"You'd think Mr. Saulsbury was crazy about me!" she laughed. "But he makes the same speeches to every girl he sees, doesn't he, Mr. Comly?"

"Indeed not," protested Archie, rallying bravely to the Governor's support. "He's been raving about you for days and my only surprise is that he so completely failed to give me the faintest idea—idea—"

"Of your charm, your ineffable beauty!" the Governor supplied. "You see, Sally, my friend is shy with the shyness of youth and inexperience and he is unable to utter the thoughts that do in him rise! I can see that he is your captive, your meekest slave. By the way, will there be cottage cheese prepared by your own adorable hand for supper? Are golden waffles likely to confront us on the breakfast table tomorrow at the hideous hour of five-thirty? Will there be maple syrup from yonder hillside grove?"

"You have said it!" Sally answered. "But you'd better chase yourselves into the house now or pop'll be peeved at having to wait for you."

On the veranda a tall elderly man rose from a hammock in which he had been reading a newspaper and stretched himself. His tanned face was deeply lined but he gave the impression of health and vigor.

"Leary," whispered the Governor in an aside and immediately introduced him.

"The road has been smooth and the sky is high," said the Governor in response to a quick anxious questioning of Leary's small restless eyes.

"Did you find peace in the churches by the way?" asked Leary.

"In one of the temples we found peace and plenty," answered the Governor as though reciting from a ritual.

Leary nodded and gave a hitch to his trousers.

"You found the waters of Champlain tranquil, and no hawks followed the landward passage?"

"The robin and the bluebird sang over all the road," he answered; then with a glance at Archie: "You gave no warning of the second pilgrim."

"The brother is young and innocent, but I find him an apt pupil," the Governor explained.

"The brother will learn first the wisdom of silence," remarked Leary, and then as though by an afterthought he shook Archie warmly by the hand.

They went into the house where Mrs. Walker, a stout middle-aged woman, greeted them effusively.

"We've got to put you both in one room, if you don't mind," she explained, "but there's two beds in it. I guess you can make out."

"Make out!" cried the Governor with a deprecatory wave of his hand. "We should be proud to be permitted to sleep on the porch! You do us much honor, my dear Mrs. Walker."

"Oh, you always cheer us up, Mr. Saulsbury. And Mr. Comly is just as welcome."

The second floor room to which Walker led them was plainly but neatly furnished and the windows looked out upon rolling pastures. The Governor abandoned his high-flown talk and asked blunt questions as to recent visitors, apparently referring to criminals who had lodged at the farm. They talked quite openly while Archie unpacked his bag. The restless activity of the folk of the underworld, their methods of communication and points of rendezvous seemed part of a vast system and he was ashamed of his enormous interest in all he saw and heard. The Governor's cool fashion of talking of the world of crime and its denizens almost legitimatized it, made it appear a recognized part of the accepted scheme of things. Walker aroused the Governor's deepest interest by telling of the visit of Pete Barney, a diamond thief, who had lately made a big haul in Chicago, and had been passed along from one point of refuge to another. The Governor asked particularly as to the man's experiences and treatment on the road, and whether he had complained of the hospitality extended by any of the agents of the underground.

"You needn't worry about him," said Walker, with a shrug. "He asks for what he wants."

"Sorry if he made himself a nuisance. I'll give warning to chain the gates toward the North. Is he carrying the sparks with him?"

"Lets 'em shine like a fool. I told 'im to clear out with 'em."

"You did right. The brothers in the West must be more careful about handing out tickets. Now trot Red up here and we'll transact a little business."

Leary appeared a moment later and Archie was about to leave the room, but the Governor insisted stoutly that he remain.

"I'm anxious for you and Red to know that I trust both of you fully."

"What's the young brother,—a con?" asked Leary with a glance at Archie.

To be referred to as a confidence man by a gentleman of Leary's professional eminence gave Archie a thrill. The Governor answered by drawing up his sleeves and going through the motions of washing his hands.

"Does the hawk follow fast?" Leary asked, as he proceeded to fill his pipe.

"The shadow hasn't fallen, but we watch the sky," returned the Governor.

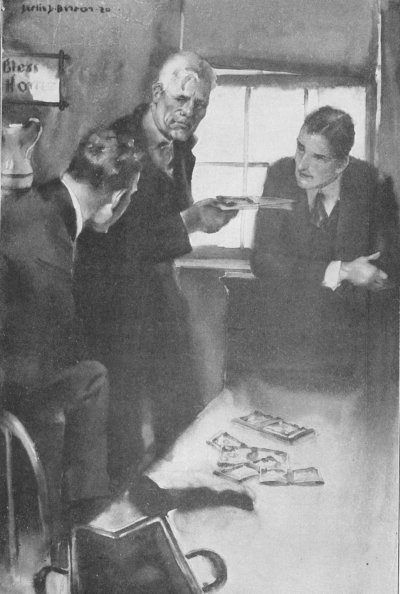

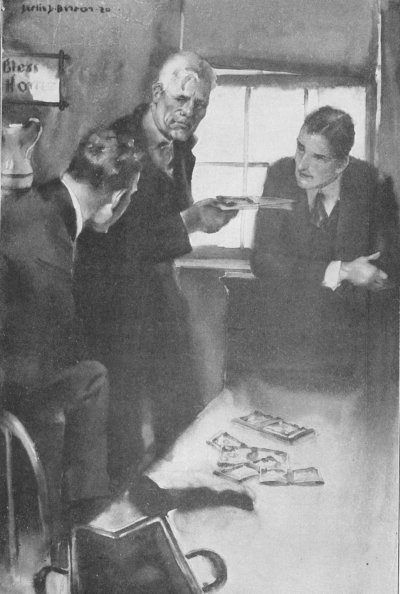

The brushing of the hands together Archie interpreted as a code sign signifying murder and the subsequent interchange of words he took to be inquiry and answer as to the danger of apprehension. He felt that Leary's attitude toward him became friendlier from that moment. There was something ghastly in the thought that as the slayer of a human being he attained a certain dignity in the eyes of men like Leary. But he became interested in the transaction that was now taking place between the thief and the Governor. The Governor extracted the sixty one-thousand-dollar bills from his bag, and laid them out on the bed. He rapidly explained just how Leary's hidden booty had been recovered, and the manner in which the smaller denominations had been converted into bills that could be passed without arousing suspicion.

"Too big for one bite, but old Dan Sheedy will change 'em all for you in Bean Center. You know his place? You see him alone and ask him to chop some feed for your cattle. He makes a good front and stands well at his bank."

Leary picked up ten of the bills and held them out to the Governor.

"If that ain't right we'll make it right," he said.

"Not a cent, Red! I haven't got to a point yet where I charge a fee for my services. But our young brother here is entitled to anything he wants."

Archie grasped with difficulty the idea that he was invited to share in the loot. His insistence that he couldn't think for a moment of accepting any of the money puzzled Leary.

"It's all right about you, Governor, but the kid had better shake the tree. If his hands are wet he's likely to need a towel."

"Don't be an ass, Comly," said the Governor. "Leary's ahead of the game ten thousand good plunks and what he offers is a ridiculously modest honorarium. Recovering such property and getting it into shape for the market is worth something handsome."

"Really," began Archie, and then as the "really" seemed an absurdly banal beginning for a rejection of an offer of stolen money, he said with a curl of the lip and a swagger, "Oh, hell! I'd feel pretty rotten to take money from one of the good pals. And besides, I didn't do anything anyhow."

The Governor passed his hand over his face to conceal a smile, but Leary seemed sincerely grieved by Archie's conduct and remarked dolefully that there must be something wrong with the money. The Governor hastily vouched for its impeccable quality and excused Archie as a person hardly second to himself for eccentricity.

"It's all right about you, Governor, but the kid better shake the tree"

"No hard feeling; most certainly not! My young friend is only proud to serve a man of your standing in the profession. It is possible that later on you may be able to render us a service. You never can tell, you know, Red."

Leary philosophically stowed the bills in his clothing.

"You're done, are you?" asked the Governor; "out of the game?"

"I sure have quit the road," Leary answered. "The old girl has got a few thousands tucked away and I'm goin' to pick her up and buy a motion picture joint or a candy and soda shop somewhere in the big lakes—one of those places that freeze up all winter, so I can have a chance to rest. The old girl has a place in mind. The climate will be good for my asthma. She knows how to run a fizz shop and I'll be the scenery and just set round."

"On the whole it doesn't sound exciting," the Governor commented, inspecting a clean shirt. "Did your admirable wife get rid of those pearls she pinched last winter? They were a handsome string, as I remember, too handsome to market readily. Mrs. Leary has a passion for precious baubles, Archie," the Governor explained. "A brilliant career in picking up such trifles; a star performer, Red, if you don't mind my bragging of your wife."

Leary seemed not at all disturbed by this revelation of his wife's larcenous affection for pearls. That a train robber's wife should be a thief seemed perfectly natural; indeed it seemed quite fitting that thieves should mate with thieves. Archie further gathered that Mrs. Leary operated in Chicago, under the guise of a confectionery shop, one of the stations of the underground railroad, and assisted the brotherhood in disposing of their ill-gotten wares. A recent reform wave in Chicago had caused a shake-up in the police department, most disturbing to the preying powers.

"They're clean off me, I reckon," said Leary a little pathetically, the reference being presumably to the pestiferous police. "That was a good idea of yours for me to go up into Canada and work at a real job for a while. Must a worked hard enough to change my finger prints. Some bloke died in Kansas awhile back and got all the credit for being the old original Red Leary."

This error of the press in recording Leary's death tickled the Governor mightily, and Leary laughed until he was obliged to wipe the tears from his eyes.

"I'm going to pull my freight after supper," he said. "Walker's goin' to take me into town and I'll slip out to Detroit where the old girl's waitin' for me."

The Governor mused upon this a moment, drew a small note-book from his pocket and verified his recollection of the address of one of the outposts of the underground which Leary mentioned.

"Avoid icy pavements!" he admonished. "There's danger in all those border towns."

Walker called them to supper and they went down to a meal that met all the expectations aroused by the Governor's boast of the Walker cuisine. Not only were the fried chicken and hot biscuits excellent, but Archie found Miss Walker's society highly agreeable and stimulating. She wore a snowy white apron over a blue gingham dress, and rose from time to time to replenish the platters. The Governor chaffed her familiarly, and Archie edged into the talk with an ease that surprised him. His speculative faculties, all but benumbed by the violent exercise to which they had been subjected since he joined the army of the hunted, found new employment in an attempt to determine just how much this cheery, handsome girl knew of the history of the company that met at her father's table. She was the daughter of a retired crook, and it had never occurred to him that crooks had daughters, or if they were so blessed he had assumed that they were defectives, turned over for rearing to disagreeable public institutions.

The Governor had said that they were to spend a day or two at Walker's but Archie was now hoping that he would prolong the visit. When next he saw Isabel he would relate, quite calmly and incidentally, his meteoric nights through the underworld, and Sally, the incomparable dairy maid, should dance merrily in his narrative. In a pleasant drawing-room somewhere or other he would meet Isabel and rehabilitate himself in her eyes by the very modesty with which he would relate his amazing tale. It pleased him to reflect that if she could see him at the Walker table with Red Leary and the Governor, that most accomplished of villains, eating hot biscuits which had been specially forbidden by his physician, she would undoubtedly decide that he had made a pretty literal interpretation of her injunction to throw a challenge in the teeth of fate.

Walker ate greedily, shoveling his food into his mouth with his knife; and Archie had never before sat at meat with a man who used this means of urging food into his vitals. The Governor magnanimously ignored his friend's social errors, praising the chicken and delivering so beautiful an oration on the home-made pickled peaches that Sally must needs dart into the pantry and bring back a fresh jar which she placed with a spoon by the Governor's plate.

At the end of the meal Walker left for town to put Leary on a train for Boston. The veteran train robber shook hands all round and waved a last farewell from the gate. Archie was sorry to lose him, for Leary was an appealing old fellow, and he had hoped for a chance to coax from him some reminiscences of his experiences.

Leary vanished into the starlit dusk as placidly as though he hadn't tucked away in his clothing sixty thousand dollars to which he had no lawful right or title. There was something ludicrous in the whole proceeding. While Archie had an income of fifty thousand dollars a year from investments, he had always experienced a pleasurable thrill at receiving the statement of his dividends from his personal clerk in the broker's office, where he drew an additional ten thousand as a silent partner. Leary's method of dipping into the world's capital seemed quite as honorable as his own. Neither really did any work for the money. This he reflected was both morally and economically unsound, and yet Archie found himself envying Leary the callousness that made it possible for him to pocket sixty thousand stolen dollars without the quiver of an eyelash.

II

The Governor, smoking a pipe on the veranda and chatting with Mrs. Walker, recalled him from his meditations to suggest that he show a decent spirit of appreciation of the Walkers' hospitality by repairing to the kitchen and helping Sally with the dishes. In his youth Archie had been carefully instructed in the proper manner of entering a parlor, but it was with the greatest embarrassment that he sought Sally in her kitchen. She stood at the sink, her arms plunged into a steaming dish pan, and saluted him with a cheery hello.

"I was just wondering whether you wouldn't show up! Not that you had to, but it's a good deal more fun having somebody to keep you company in the kitchen."

"I should think it would be," Archie admitted, recalling that his mother used to express the greatest annoyance when the servants made her kitchen a social center. "Give me a towel and I'll promise not to break anything."

"You don't look as though you'd been used to work much," she said, "but take off your coat and I'll hang an apron on you."

His investiture in Mrs. Walker's ample apron made it necessary for Sally to stand quite close to him, and her manner of compressing her lips as she pinned the bib to the collar of his waistcoat he found wholly charming. His heart went pit-a-pat as her fingers, moist from the suds, brushed his chin. She was quite tall; taller than Isabel, who had fixed his standard of a proper height for girls. Sally did not giggle, but acted as normal sensible girls should act when pinning aprons on young men.

She tossed him a towel and bade him dry the plates as she placed them on the drain board. She worked quickly, and it was evident that she was a capable and efficient young woman who took an honest pride in her work.

"You've never stopped here before? I thought. I didn't remember you. Well, we're always glad to see the Governor, he's so funny; but say, some of the people who come along—!"

"I hope," said Archie, turning a dish to the light to be sure it was thoroughly polished, "I hope my presence isn't offensive?"

"Cut it out!" she returned crisply. "Of course you're all right. I knew you were a real gent the first squint I got of you. You can't fool me much on human nature."

"You've always lived up here?" asked Archie, meek under her frank approval.

"Certainly not. I was born in Missouri, a grand old state if I do say it myself, and we came here when I was twelve. I went through high school and took dairying and the domestic arts in college and I'm twenty-three if you care to know."

He had known finishing-school girls and college girls and girls who had been educated by traveling governesses, but Sally was different and suffered in no whit by comparison. Her boasted knowledge of the human race was negligible beside her familiarity with the mysterious mechanisms of cream separators and incubators. Fate had certainly found a strange way of completing his education! But for the shot he had fired in the lonely house by the sea, he would never have known that girls like Sally existed. As he assisted her to restore the dishes to the pantry, she crossed the kitchen with queenly stride. Isabel hadn't a finer swing from the hips or a nobler carriage. When he abandoned his criminal life he would assemble somewhere all the girls he had met in his pilgrimage. There should be a round table, but where Isabel sat would be the head, and his sister should chaperone the party. When it dispersed he would tell Isabel, very honestly, of his reaction to each one, and if she took him to task for his susceptibility it would be a good defense that she was responsible for sending him forth to wrestle with temptation.

When the kitchen was in perfect order they reported the fact to Mrs. Walker and Sally suggested that they stroll to a trout brook which was her own particular property. The stream danced merrily from the hills, a friendly little brook it was—just such a ribbon of water as a girl like Sally would fancy for a chum.

"We must have a drink or you won't know how sweet and cool the water is!" She cupped her hands and drank; but his own efforts to bring the water to his lips were clumsy and ineffectual.

"Oh you!" she laughed. "Let me show you!"

Drinking from her hands was an experience that transcended for the moment all other experiences. If this was a rural approach to a flirtation, Miss Seebrook's methods were much safer, and the garden of the Cornford tavern a far more circumspect stage than a Vermont brookside shut off from all the world.

He had decided to avoid any reference to the secrets of the underground trail, but his delicacy received a violent shock a moment later, when they were seated on a bench beside the brook.

"Do you know," she said, "you are not like the others?"

"I don't understand," he faltered.

"Oh, cut it out! You needn't try to fool me! When I told you awhile ago I thought you were nice, I meant more than that; I meant that you didn't at all seem like the crooks that sneak through here and hide at our house. You're more like the Governor, and I never understand about the Governor. It doesn't seem possible that any one who isn't forced by necessity into crime would ever follow the life. Now you're a gentleman, any one could tell that, but I suppose you've really done something pretty bad or you wouldn't be here! Now I'm going to hand it to you straight; that's the only way."

"Certainly, Miss Walker; I want you to be perfectly frank with me."

"Well, my advice would be to give yourself up, do your time like a man and then live straight. You're young enough to begin all over again and you might make something of yourself. The Governor has romantic ideas about the great game but that's no reason why you should walk the thorny road. Now pop would kill me if he knew I was talking this way. It's a funny thing about pop. All I know about him I just picked up a little at a time, and he and ma never wanted me to know. Ma's awful nervous about so many of the boys stopping here, for she hung on to pop all the time he was shooting up trains out West, and having a husband in the penitentiary isn't a pleasant thing to think about. Ma's father ran a saloon down in Missouri; that's how she got acquainted with pop, but ma was always on the square, and they both wanted me brought up right. It was ma's idea that we should get clean away from pop's old life, and she did all the brain work of wiping the slate clean and coming away off here. We were a couple of years doing it, trying a lot of other places all over the country before they struck this ranch and felt safe. Pop's living straight; you needn't think he isn't, but he's got a queer hankering to see the sort of men he used to train with. It's natural, I suppose."

"I suppose it is. But you must have suffered; I can imagine how you feel," said Archie, who had listened to her long speech with rapt attention.

"Well, I don't know that I've suffered so much," she replied slowly, "but I do feel queer sometimes when I'm around with young folks whose fathers never had to duck the cops. Not that they've any suspicions, of course; I guess pop stands well round here."

"I can understand perfectly how your father would like to see some of the old comrades now and then and even give them shelter and help them on their way. That speaks highly for his generosity. It's a big thing for me right now to be put up here. I'm in a lot of trouble, and this gives me a chance to get my bearings. I shall always remember your father's aid. And you don't know how wonderful it is to be sitting beside you here and talking to you just as though nothing had ever happened to me; really as though I wasn't a lost sheep and a pretty black one at that."

"I'm sorry," she answered. "When I told you you'd better go and do your time and get done with it, I didn't mean to be nasty. But I was thinking that a man as sensitive as I judge you to be would be happier in the long run. Now pop had an old pal who drifted along here a couple of years ago, and pop had it all figured out to shoot him right up into Canada, but, would you believe it, that man simply wouldn't go! The very idea of being in a safe place where he was reasonably certain of not being bothered worried him. He simply couldn't stand it. He was so used to being chased and shot at it didn't seem natural to be out of danger, and pop had to give him money to take him to Oklahoma where he'd have the fun of teasing the sheriffs along. And he had his wish and I suppose he died happy, for we read in the papers a little while afterward that he'd been shot and killed trying to hold up a bank."

Archie expressed his impatience of the gentleman who preferred death in Oklahoma to a life of tranquillity in the Canadian wilds.

"Oh, they never learn anything," Sally declared. "I wouldn't be surprised if pop didn't pull out some time and beat it for the West. It must be awful tame for a man who's stuck pistols into the faces of express messengers and made bank tellers hand out their cash to settle down in a place like this where there's nothing much to do but go to church and prayer meeting. I don't know how many men pop's killed in his time but there must be quite a bunch. But pop doesn't seem to worry much. It seems to me if I'd ever pumped a man full of lead I'd have a bad case of insomnia."

"Well, I don't know," remarked Archie, weighing the point judicially. "I suppose you get used to it in time. Your father seems very gentle. You probably exaggerate the number of his—er—homicides."

He felt himself utterly unqualified to express with any adequacy his sympathy for a girl whose father had flirted with the gallows so shamelessly. Walker had courageously entered express cars and jumped into locomotive cabs in the pursuit of his calling and this was much nobler than shooting a man in the back. Sally would probably despise him if she knew what he had done.

She demurred to his remark about her father's amiability.

"Well, pop can be pretty rough sometimes. He and I have our little troubles."

"Nothing serious, I'm sure. I can't imagine any one being unkind to you, Sally."

"It's nice of you to say that. But I'm not perfect and I don't pretend to be!"

Sympathy and tenderness surged within him at this absurd suggestion that any one could harbor a doubt of Sally's perfection. Her modesty, the tone of her voice called for some more concrete expression of his understanding than he could put into words. Her hand, dimly discernible in the dusk of the June stars, was invitingly near. He clasped and held it, warm and yielding. She drew it away in a moment but not rebukingly. The contact with her hand had been inexpressibly thrilling. Not since his prep school days had he held a girl's hand, and the brook and the stars sang together in ineffable chorus. It was bewildering to find that so trifling an act could afford sensations so charged with all the felicity of forbidden delight.

"I wonder," she said presently; "I wonder whether you would—whether you really would do something for me?"

"Anything in my power," he declared hoarsely.

"What time is it?" she asked with a jarring return to practical things.

She bent her head close as he held a match to his watch. It was half past eight.

"We'll have to hurry," she said. "When I told you pop and I didn't always agree about everything I was thinking—"

"Is it about a man?" he asked, surmising the worst and steeling himself for the blow if it must fall. He would show her how generously chivalrous a man could be toward a girl who honored him with her confidence and appealed for his assistance.

"It would be a long story," she said sadly, "and there isn't time to tell it, but the moment I saw you were so big and brave and strong, I thought you might help."

To be called big and brave and strong by so charming a person, to enjoy her confidence and be her chosen aid in an hour of need and perplexity profoundly touched him. He wished that Isabel could have heard Sally's tribute to his strength and courage—Isabel who had said only a few days ago that he wouldn't kill a flea. He had always been too modest and too timid, just as Isabel had said, but those days were passed and the man Isabel knew was very different from the man who sat beside Bill Walker's daughter under the glowing Vermont stars. Drums were beating and bugles sounding across the hills as he waited for Sally to send him into the li