CHAPTER XIV

CALEB CONOVER LOSES AND WINS

“I don’t quite understand,” ventured the puzzled lawyer.

“Neither do I,” said Caleb. “Tell me your story as brief as you can.”

“Your son reached town a little after six o’clock this evening,” answered Wendell. “It seems he went directly to a restaurant in the theatre district of Broadway, a place frequented by men of a certain class and by the women they take there. It was early, but on account of the election night fun to come later many people were already dining. Gerald afterward told me he went there in the hope of catching a glimpse of his former wife. He saw her there. With her was a man she had known before she met your son, a bookmaker named Stange, whom Gerald—or Gerald’s money—had originally won her from, and for whom he always, it appears, retained some jealousy. Gerald walked straight up to the table where they sat, drew a revolver and fired four times point-blank in Stange’s face. Any one of the shots by itself would have been fatal. Then he tossed the revolver to a waiter and spent the time until the police arrived in trying to console this Montmorency woman and to quiet her hysterics. They took him to the Tenderloin station and he got the police to telephone for me. I found him in a state of semi-collapse. A police surgeon was working over him. Heart failure brought on by excitement. His heart was already in a depressed, weakened state, the surgeon said, from an overdose of morphine. The poor boy apparently was in the habit of taking it, for they found a case with a hypodermic syringe and tablets in his pocket. And one of his arms——”

“So that was the ‘third thing’ beside booze and cigarettes?”

It was Caleb’s first interruption. During the recital of his son’s crime he had stood motionless, expressionless. Not until this trivial detail was reached had he spoken. And even now his voice was as emotionless as was his face. The inscrutable Spartan quiet that had so often left his business and political opponents in the dark was now upon him. Wendell saw and wondered. Mistaking the other’s mental attitude for the first daze of horror, he resumed:

“He came around in a few minutes. I did what I could for him. Then I tried to reach you by long-distance telephone. But the wires were down all through this State. I had no better fortune in telegraphing. So I caught the eight-ten train and came straight here. I thought you ought to be told at once, so that——”

“Quite so. Thank you. It was very white. I’m sorry I was so brisk with you awhile ago.”

The lawyer stared. Conover was talking as though a mere financial matter were involved. Still supposing his client suffering from shock that dulled his sensibilities, Wendell continued:

“Morphine and jealousy combining to cause temporary insanity. That must be our line of defence. You agree with me of course?”

“Suit yourself. I’ll stand by whatever you suggest.”

The lawyer drew out his watch.

“Twelve forty-five,” he said. “The New York express passes through Granite at one twenty. We’ll have plenty of time to catch it. If you will get ready at once, we’ll start. We can discuss details during the trip.”

“‘We’?” echoed Caleb. “What d’ye mean? I’m not going to New York with you.”

“Mr. Conover!” exclaimed Wendell, shaking his inert host by the shoulder to rouse him from his apparent stupor, “you don’t realize! Gerald is in a cell on a murder charge. To-morrow he will be sent to the Tombs—our city prison—to remain until his case comes up. Then he will be tried for his life and——”

“I know all about the course of such things. You don’t need to tell me.”

“But this is a life-and-death matter!”

“Well, if I can keep cool over it, I presume you can, can’t you? It’s very kind of you to explain all this to me, but it ain’t necessary. I understand everything you’ve told me, and I understand a lot you’ve overlooked. For instance, the pictures that’ll be in all to-morrow’s evening papers of my boy on his way to the Tombs, handcuffed to a plain-clothes man, and pictures of that chorus woman of his in all sorts of poses, and pictures of the ‘stricken father’—that’s me—and Letty figuring as the ‘aged mother, heart-broke at her son’s crime.’ And my daughter and her—the Prince d’Antri. And my house and a diagram of the restaurant where the shooting was done. And there’ll be interviews with the Montmorency thing and accounts of her being brave and visiting Jerry in the Tombs. And a maynoo of what he’ll have for Thanksgiving dinner in his cell. And——”

“I’ll do what I can to prevent publicity. I——”

“You’ll do nothing of the sort. What happens in public the public has a right to read about. If Jerry’s dragged us into the limelight, can we kick if the papers let folks see us there?”

“But surely——”

“That’s the easiest part of it. I’ve got to face my wife with this story. Not to-night, but to-morrow anyhow. Sweet job, eh? A white man don’t enjoy squashing the life out of even a guinea-pig in cold blood, let alone a boy’s mother. And reporters’ll begin coming here by sunrise for interviews, and folks’ll be staring at us in the street and offering their measly sympathy and then running off to tell the neighbors how we took it. And every paper we pick up will be full of the ‘latest d’vel’pments’ and all that. And those of us who know Jerry will get into the pleasing habit of remembering what a cute, friendly kid he used to be when he was little, and the great things we used to dream he’d do when he grew up, and how we hustled so’s he’d have as good a chance in life as any young feller on earth. And then we’ll remember he’s waiting in jail to be tried for murdering a chorus slattern’s lover, and all the black, filthy shame he’s put on decent folks that was fools enough to love him, and the way he’s fulfilled them silly hopes of ours. Oh, yes, Wendell, I guess I ‘realize,’ all right, all right. I don’t need no ‘wakening sense.’ But maybe I’ve made it clear to you now why it is I don’t go cavorting off by the next train to console and cheer up the boy who’s brought this on us. I don’t just hanker——”

“Don’t take that tone, I beg, sir!” pleaded the lawyer, deeply pained by what underlay the father’s half-scoffing, ironical tirade. “He may live it down. He is only twenty-four. The jury will surely be lenient. After all, there’s the ‘unwritten law’ and——”

“And of all the slimy rot ever thought up by a paretic’s brain, that same ‘unwritten law’ is about the rankest specimen,” snarled Caleb. “By the time a man’s learned to live up to all the written laws, I guess he won’t have a hell of a lot of leisure left to go moseying around among the unwritten ones. Whenever a coward takes a pot-shot at some one within half a mile of a petticoat, up goes the ‘unwritten law’ scream. Use it if you like in the trial, but for God’s sake cut out such hypocritical bosh when you’re talking to me. ‘Unwritten law!’ Why don’t the Legislature take a day off and write it?”

“Then you won’t come with me to town?” asked the lawyer, with another covert glance at his watch.

“Come with you and tell Jerry how sorry I am for him, and how I sympathize with him for killing his mother—for that’s what it’ll come to—and for wrecking a name I’ve spent all my life building up for him, and for making me the shame of all my friends? No, Wendell, I guess I’ll have to deprive him of that treat. I’ll think up later what’s best to do about him. In the meantime get him acquitted.”

“Acquitted? That is not so easy. But——”

“Not so easy? Why ain’t it? Didn’t I tell you to draw on me for all you wanted? I’ve got somewhere between forty and fifty millions all told. The jury don’t live this side of the own-your-own-cloud suburbs of heaven that hasn’t at least one man on it that $100,000 will buy. If not that, then $1,000,000. I’ll leave the details to you. Buy enough jurors to ‘hang’ every verdict till they get tired of trying Jerry and turn him loose to save the State further expense. If a murderer ain’t convicted on his first trial, it’s a cinch he’s never going to be on his second or third. Now, it’s up to you to buy that drawn verdict for the first trial, and then for the others till they acquit him or parole him in your custody. It’s been done before, and it’ll be done again. This ain’t a ‘life-and-death matter’ as you called it. It’s a question of dollars and cents. And as long as I’ve got enough of those same dollars and cents, no boy of mine’s going to the death-chair or to life imprisonment either. You’ll have to hustle for that train. If you miss it, come back and I’ll put you up for the night.”

Tense excitement, as was lately his way, had made the formerly taciturn Railroader voluble. He now, as frequently since the night of his speech at the reception, noted this, himself, with a vague surprise.

“If Jerry wants any ready money, just now——” he began, as he escorted the lawyer to the door.

“He seems to have plenty for any immediate needs,” returned Wendell. “I saw the contents of his pockets that the police had taken charge of. Besides the morphine case and a few cards and a packet of letters in a sealed wrapper, there were large-denomination bills to the amount of——”

“Packet of letters—sealed?” croaked Conover, catching the other’s arm in a grasp that bit to the point of agony. “Letters?” he repeated, his throat dry and contracted.

“Oh, I meant to speak to you about them. Gerald asked me to bring them along. He said he got them for you from a man in Ballston to-day, and was to have sent them to you by registered mail. But in the hurry of catching the New York train and the excitement over the prospects of seeing——”

“Where are they? Did you bring them?”

“I couldn’t,” answered Wendell, marveling at the lightning change in his client’s voice and face. “The police, of course, took charge of them. They will have to be examined by the district attorney’s office before——”

“You must hurry or you’ll miss your train. Good night.”

Conover slammed the door on his astonished guest and walked back into the library.

In the middle of the room where he had so vainly sought to inculcate into his family the “pleasant home hour” habit, the Railroader now stood alone, silent, without motion, his shrewd face an empty, expressionless mask of gray, his eyes alone burning like live coals, showing that the brain within in no way shared the outer shell’s inertia.

“I’ve got to work this out later, when I’ve more time,” he muttered.

And with the resolve came the impulse so common to him when troubled or excited.

“Gaines!” he called to the butler, who, late though the hour was, had not received permission on this great night to retire, “Gaines! order Dunderberg saddled and brought around in fifteen minutes, and have Giles ride with me to-night.”

Caleb went up to his dressing-room and hastily changed into his riding clothes.

As he strapped on the second of his spurs a confused babel of sound arose just beyond his dressing-room. This apartment served as a sort of antechamber to the study. The noise, therefore, must have come, he knew, from the bevy of men he had left there. This patent fact dawned on Conover as a surprise. He had forgotten his followers’ existence, forgotten the undecided election, the impending Grafton returns on which its result would hang. He had even, since Wendell’s departure, forgotten Jerry’s plight and his own rage and mortification thereat. All life—all the future—now concentrated, for him, about the Denzlow packet, whose contents must by this time, or by morning at latest, be known to the authorities. This last and greatest blow had filled all his emotions, driving out lesser thoughts, fears, hopes and griefs, as a cyclone might rip to thin air the dawn mists over a lake.

Now, at the clamor in the study, he pulled himself together. The iron will still held. He strode to the connecting door and opened it. The tumult had died down, and Staatz alone was now speaking. So intent were the speaker and his hearers that none noted the Boss’s advent from so unexpected a quarter. On the threshold stood Caleb, surveying the scene with quiet contempt.

“And that’s how it is!” Staatz was declaiming. “We’re licked. Licked! Pretty sort of news for Democrats this is!” picking up a newly-broken length of ticker tape around which the other men had been clustering. “‘City of Grafton, complete: Conover 5,100, Standish 12,351.’ Is it a wonder you all went nutty when you got it? In Grafton, too, stronghold of Democracy. This means the State for Standish by an easy 4,000, maybe more. And who’s to blame? Are you? Am I? Not us! We’ve had—the whole party’s had—our hands tied behind us. And we were sent in to fight like that. Could we use the good old moves? Not us! It must be kid-glove, silk-sock, amachoor politics, meeting Standish on his own ground. No wonder he licked us! A Prohibitionist could have licked men that were hampered like we were. And who was it tied our hands? Who got the party beat and the Machine smashed? Who did it? Caleb Conover!”

He paused panting and sweating with wrath. Then, encouraged by a murmur of assent that ran around the ring of listeners, he bellowed:

“We ain’t in politics for our health, are we? It’s our bread and butter. That bread and butter’s been snatched away from us. Who by? Caleb Conover! Are you going to be led by the nose any longer by a man who betrays you like that? For my part I’m tired of wearing his collar.”

A growl of approbation greeted his query. His bellow changed to a lower tone of persuasion.

“I ain’t saying,” he resumed, “but what Conover’s done work for the Machine. In his day he was a great man, but his day’s past. He’s breaking up. Don’t this campaign prove he is? Makes us throw our chances out of the winder for Standish to pick up. And when we’re waiting news from the deciding city he plays a phonograph, and then wanders off and most likely forgets we’re here. There’s another thing: How did Richard Croker and Charlie Murphy and Matt Quay and N. Bonaparte and all the rest of the big bosses hold their power? By keeping their mouths shut. When Croker once began to talk, what happened? Down tumbled all his power. Same with Quay. Same with N’poleon. Same with all of ’em. Talking was the first sign of losing hold. Look at Conover’s case. We can all remember when words was as hard to get out of him as dollars. How about him now? Talks to any one. I tell you he’s breaking up. Unless we want the Machine to break up for good and all, too, we got to get a new Leader.”

“If the new Leader’s you, Adolphe Staatz,” cut in a rasping snarl, like a dog’s, from the group of politicians, as Billy Shevlin shouldered his way forward and thrust his unshaven face close to the district leader’s bristling gray mustache, “if you’re the new Leader you’re rootin’ for, let me put you wise to somethin’: You’ll go to the primaries straight from the hospital, an’ with your shyster mug in a sling. Fer, if I hear another peep out of you, roastin’ the Boss, I’ll knock you from under your hat, and push your ugly face in till your back teeth bend. You take the Boss’s job? Chee! It’s to ha-ha! Go chase yourself, ’fore I chase you so far you’ll d’scover a new street. You’d backtrack Mister Conover, would you’se? Why, if you go ’round Granite spreadin’ idees of that kind in your own pin-head brain, I’ll sure be c’mpelled to do all sorts of things to you. An’ when I’m finished with you the Staatz family’ll be able to indulge in that alloorin’ pastime called ‘Put Papa Together!’ You fer Leader, eh? Say! I’m flatterin’ you a whole heap when I call you——”

“Let him alone, Billy,” intervened Bourke, as the startled Staatz backed toward the wall, ever followed by that belligerent, blue-jawed little face so close to his own—“let him alone. He’s talking straight. I for one——”

“You for one,” sounded a sneering voice from the dressing-room doorway behind them, “you for one, friend Bourke, were starving on the street when I took you in and fed you and got your kids out of the Protectory and gave you a job.”

At the first word the mumbled assent to Staatz’s and Bourke’s opinion, that had welled up in a dozen throats, died into sacred silence.

“You for another, ’Dolphe Staatz,” went on Caleb, still standing on the threshold and viewing the group of malcontents with a cold disgust. “You were on the road to the ‘pen’ for knowing too much about that ‘queer paper’ joint on Willow Street, when I got the indictment quashed and squared things with the district attorney and put you on your feet.

“Caine,” turning to the Star’s editor, “I think I heard you agreeing among the rest, didn’t I, hey? Diff’r’t sound from the kind you made when you come to me twelve years ago and cried and said the Star was all in, and would I save you from going bankrupt by taking it over? And there’s plenty more of you here with the same sort of story to tell.”

He strode forward and was among them, forcing one after another to meet his eye, dominating by his very presence the men who had sought to dethrone him. In his hour of stress all the old power, the splendid rulership of men, surged back upon the Railroader. He stood a king amid awestruck serfs, a stern schoolmaster among a naughty band of scared children.

“Some one spoke about being tired of wearing my collar,” he said. “Is there a man here who put on that collar against his will, or a man who didn’t beg for it? Is there a man who hasn’t profited by it? A man who hasn’t risen as I have risen and benefited when I benefited? Don’t stand there, mumchance, like a lot of dago section-hands! You were ready enough to speak before I came in. Why aren’t you, now? Is it because you’re so sorry for this poor, broken old man, who talks too much and ain’t fit to run the Machine any longer, eh? Spit it out, Staatz! If you’re qualifying for my shoes you got to learn to look less like a whipped puppy when you’re spoke to. Stand up and state your grievance like a man, you Dutch crook that I lifted out of jail! You, too, Bourke! Where’s your tongue? And all the rest of you that was on the point of choosing a new Leader.”

No one answered. The Boss’s instinct power rather than his mere words held them sulky and dumb. Over each was creeping the old subservience to the peerless will that had so long shaped the Mountain State’s destinies and theirs.

“I talk too much, eh?” mocked Conover. “Well, to prove that’s so, I’m going to give you curs a little Sunday-school talk right now. You say I cut out the old methods, this campaign. I did. And why did I do it? Because if these reformers had thought they were licked unfair there’s so many of ’em they’d ’a’ carried the case to every court in the land, and ’a’ drawed the whole country’s op’ra-glasses onto this p’ticular Machine, and started another such wave as swamped Dick Croker and Tammany in ’94. And then where’d the Machine and you fellers have been? There’s got to be reform in a State just so often, just like there’s got to be croup in a nursery. Every other State’s had it. And each time they’ve fished up something queer about their local Machine, and that same Machine’s never been so strong again. Well, the Mountain State’s turn for reform was overdue. It had to come. And this was the time. I thought maybe I could beat ’em on their own ground. If I had, that’d ’a’ ended reform here, forever and amen. Even if I was beat I knew the people would get so sick of one term of reform, they’d come screeching to us to take ’em back. And then’s the time my kid-glove stunts of this campaign would shine out fine against a rotten reform administration. The Machine would escape any investigation of the kind that follers a crooked campaign, and we’d simply be begged to take everything in sight for the rest of our lives. Maybe you think a chance of one term out of office was too much to pay for such a future cinch?”

The speech—reasons and all—was improvised as he spoke. And again it was the Boss’s manner and his brutal magnetism rather than his words that carried conviction.

“Because I didn’t print this all out in big letters and simple words that you dolts could understand,” resumed Caleb, “you forget the holes I’ve got you and the party out of in the past, and go grouching about my ‘breaking up.’ Maybe my brain is softening a bit, just to keep company with the ninnies I travel with. But it’s still a brain. And that’s more’n anyone else here can boast of having. Now, I’ve showed you how the land lays. Which of you would ’a’ carried the Machine over it any safer, and how would he’d ’a’ done it? You, for instance, Staatz?”

The big German sheepishly grumbled something unintelligible under his breath.

“Sounds about as clear and sensible as most of your ideas, ’Dolphe,” commented Caleb. “You’ll have to learn more words’n that before you’re Boss. Now, then,” he resumed, throwing aside his stolid bearing and hammering imperiously on the table with his riding crop, “we’ll proceed to choose a new Leader. It’s irregular, but there’s easy a quorum of district leaders here. Who’ll it be that steps into Caleb Conover’s shoes? Who’ll say he’s strong enough to hold the reins he thinks I’m too weak to handle? Who’ll it be? I lifted the party and every man here from the dirt to a higher, stronger place than anyone dreamed they could be lifted. Who’ll hold ’em there now that I stand aside? Speak up! Choose your leader!”

“CONOVER!” yelled Billy Shevlin ecstatically.

“Shut up, you mangy little tough!” fiercely ordered Caleb; but a half-score of eager voices had caught up the cry. About the Railroader pressed the district leaders, smiting him on the back, striving to grab his hands, over and over again vociferating his name; crying out on him to stand by them, to lead them, to forgive their ingratitude and folly.

And in the centre of the exultant babel stood Caleb Conover, unmoved save for a sneering smile that twisted one corner of his hard mouth, the only man present who was not carried away by that crazy wave of reactive enthusiasm.

“Staatz,” observed the Railroader, as the hubbub at length died down, “I’m afraid you’ll have to wait a wee peckle longer for that leadership. But cheer up. Everything comes to the man who waits—till no one else wants it. I’ve got one thing more to say, and then my ‘talking’ will be done for good, as far as you men are concerned. I had a kennel of dogs once, on my place here. A whole lot of pedigreed, high-priced whelps that it cost me a fortune to buy. I thought maybe I’d enjoy their society. It was so much sensibler’n politicians’. But somehow after a while I got tired of ’em. For they didn’t take to me, not from the first. Animals don’t, as a rule. Every now and then when I’d go to their enclosure they’d forget to mind me, and once or twice they combined and tried to get me down and throttle me. Of course I could lash ’em into minding, and I could lash all the fight out of ’em when they started for my throat. And I did. But by and by I got tired of having to lick the brutes every few days in order to make ’em treat me decent. They weren’t worth the trouble. So I got rid of them. Just as I’m going to get rid of you fellers, and for the same good reason. I resign. I’m out of politics for good. As far as I’m concerned the Machine is smashed for all time. Now clear out of here, the whole kennelful of you. Be on your way!”

Stilling the furious volley of protest that had arisen on all sides at his announcement, Caleb flung open the outer door of his study. Several of the dazed politicians essayed to speak, but the quick gleam in their self-deposed Leader’s eye halted the words ere they were spoken. Obedient, cowed to the last, the Machine’s officers and henchmen finally yielded to that look and to the peremptory gesture of the Railroader’s arm. One by one they filed out, Staatz in the van, Bourke with averted gaze slinking along in the rear.

With a grunt of ultimate dismissal Conover closed the door.

Glancing over the scene of the late conflict before departing for his ride, his glance fell on a solitary, ill-dressed figure seated at one corner of the deserted table.

“Billy!” exclaimed Conover, exasperated, “why didn’t you get out with the rest!”

“’Cause I don’t belong with that cheapskate push. I belong here with you, Boss.”

“But I’m out of it, you idiot. Out of the game for good and all. I’m leaving Granite.”

“When do we start?”

Conover looked at his little henchman in annoyance that merged into a vexed laugh.

“I tell you,” he repeated, “I’m out of politics for good.”

“So’m I, then,” cheerfully responded Billy. “D’ye know, Boss, I’m kind o’ glad. Sometimes I’ve suspicioned politics wasn’t—well, wasn’t quite square. Maybe it’s best that two pious men like us is out of it. Now, say, Mister Conover,” he hurried on more seriously, “I know what you mean. You want to shake the whole bunch. You’re sore on ’em all. You’re goin’ to cut out Granite, too, after the lemon you’ve been handed. But whatever your game is an’ wherever you spiel it, it won’t do you no harm to have Billy Shevlin along with you as a ‘also-ran.’ Now, will it? Why, Boss, I’ve worked for you ever since I was no bigger’n—no bigger’n Staatz’s chances of becomin’ a white man. An’ I ain’t goin’ to cut out the old job at this time of day. If it ain’t Caleb Conover, Governor, I work for, then it’ll be Caleb Conover, Something-or-other. An’ that’s good enough for W. Shevlin. So let’s let it go at that. I won’t bother you no more to-night, ’cause I see you’re on edge. But I’m comin’ around in the mornin’. An’ when I come I’m comin’ for keeps. Just like I’ve always done. So long, Boss.”

“Poor old Billy!” muttered Conover as the Shevlin slipped out too hurriedly to permit of his Leader’s framing any reply to what was quite the longest speech the henchman had ever made. “He’ll never make a hit in politics till he gets rid of some of that loyalty. Next to gratitood there ain’t another vice that hampers a man so bad.”

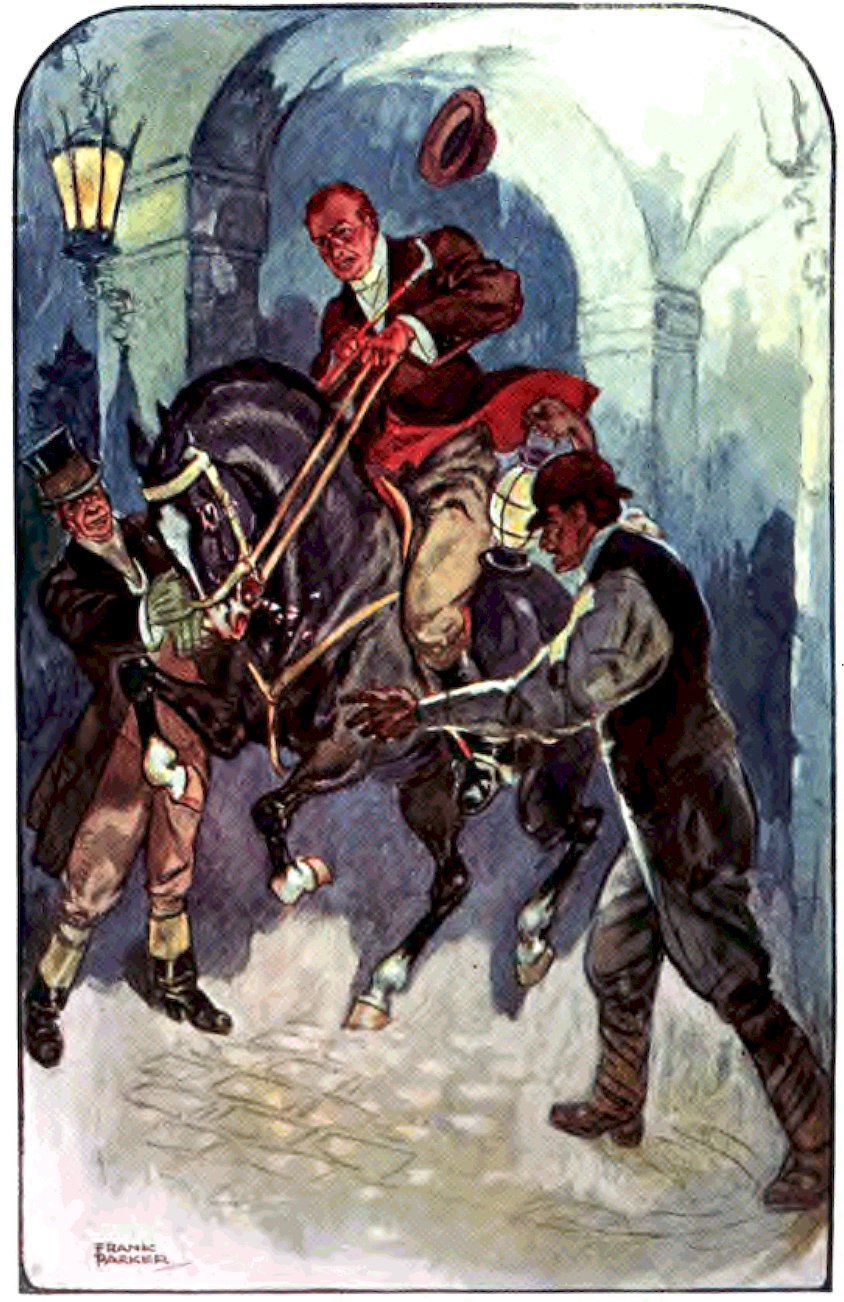

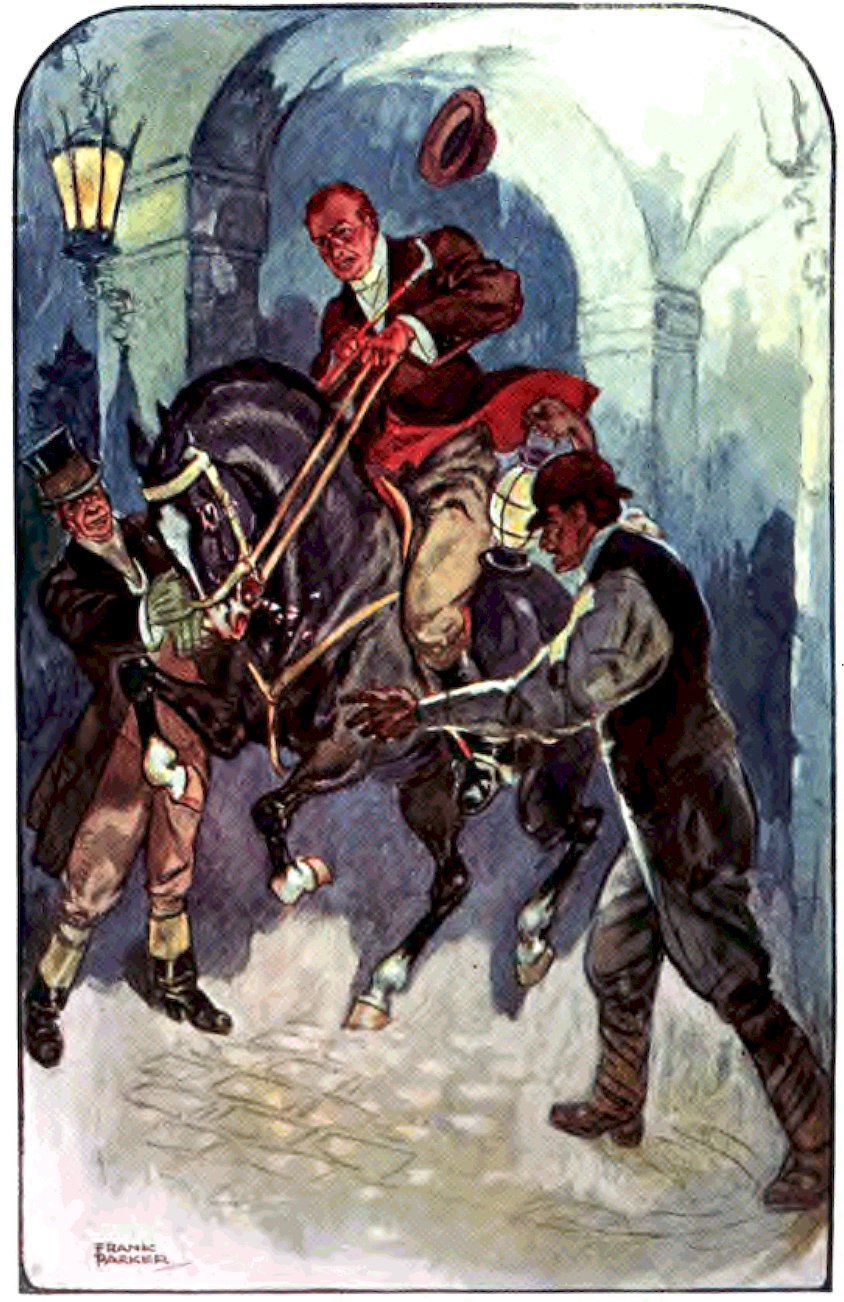

Then, dismissing the recent events from his mind, the Railroader ran downstairs, lightly as a boy, and to the outer entrance, where Dunderberg was plunging and pivoting in the grip of two grooms. A third groom, mounted on a quieter steed, sat well beyond range of the stallion’s lashing heels.

Late as it was, Mrs. Conover was still up. Caleb brushed past her in the hall, cutting short the feeble remonstrances with which she always prefaced one of his wild rides.

“Oh, Caleb!” she pleaded as she followed him out on the broad veranda. “Not to-night, dear! Just give it up this once, to please ME! He’s—he’s such a terrible horse. I never saw him so wild as he is now. The men can scarcely hold him. Oh, please——”

“All right!” shouted Conover, in glorious excitement. “All right! Let him go! Never mind the hat.”

But the Railroader was already preparing to mount.

“Don’t you worry, old girl,” he called back over his shoulder; “he’s none too wild for my taste. There never was a horse yet could get the best of me.”

The wind was rising again. It whistled across the grounds, ruffling the puddles and stirring the dead leaves. A whiff of it caught Conover’s hat as he fought his way to the plunging stallion’s back. The exultance of coming battle was already upon both rider and horse.

“Your hat, sir!” called one of the grooms, as another sprang forward to catch the falling headgear. But Caleb had no mind to wait for trifles. The night wind was in his face, the furious horse whirling and rearing between his vice-like knee-grip.

“All right!” shouted Conover in glorious excitement, signalling to the struggling groom to release the bit. “All right! Let him go! Never mind the hat. Come on, Giles.”

Dunderberg, his head freed, leaped forward as from a catapult. Master and man thundered away down the drive, and were swallowed in the blackness. The double roar of flying hoofs grew fainter, then was lost in the solemn hush of the autumn night.