CHAPTER III

CALEB CONOVER REGRETS

Caleb Conover, Railroader, was in a humor when all the household thought well to tread softly.

It was the morning after his “début.” He paced his study intermittently, stopping now and again at a window to watch laborers at work in the grounds below, dismantling the strings of Chinese lanterns, and carting away other litter of the festivities. A pile of newspapers filled one of the study chairs. On the front page of each local journal was blazoned a garish account of the Conover reception. Yet Caleb, eager as he had once been to read every word concerning the fête, had not so much as glanced at any of the papers. In fact, he seemed, in his weary pacing to and fro, to avoid the locality of the chair where they lay.

For an hour—in fact, ever since he had left his bedroom—he had paced thus. And none had dared disturb him. For the evil spirit was heavy upon Saul, and the javelin of wrath, at such times, was not prone to tarry in its flight.

Caleb’s black mood this morning came from within, not from objective causes. He was travelling through that deepest, most horrible of all the multi-graded Valleys of Humiliation—the Vale of Remembered Folly. Let a man recall a crime, and—especially if he be troubled at the time with indigestion—remorse of a smug if painful sort will be his portion. Let him recall a misfortune, and a wave of gentle, self-pitying grief will lave his heart, soothing the throb of an old sting into soft regret. But let him awake to the fact that he has made himself sublimely ridiculous—and that in the presence of the multitude—and his self-torture can be lashed to a pitch that shames the Inquisition’s most zealous efforts. Therein lies the True Valley of Humiliation, the ravine where no sunlight of redeeming circumstances shines, where no refreshing rill of excuse and palliation flows. And it was in this unrelieved, arid gorge of self-contempt that Caleb Conover now wallowed.

He had made a fool of himself. An arrant fool. He had drunk until he was drunken. And in that drunkenness he had spoken blatant words of idiocy. He had made himself ridiculous in the eyes of the very class he had sought to cultivate. His had not been the besottedness that babbles, sleeps and forgets. Even as his drink-inspired tongue had betrayed no thickness nor hiatus during his drivelling speech, so the steady brain had, on waking, remorselessly told him of his every word.

Thirty years before, in a drunken spree, he had been seized with a fervor of patriotism and had enlisted in the army. On coming to himself it had cost him nearly every dollar he possessed to get himself free. After a similar revel, a year later, he had stampeded a meeting of the local “machine” by making a tearful speech in favor of reform and purity in politics. The oration had cost him his immediate chances of political preferment. After that he had done away with this single weakness in his iron nature and had drunk no more. The sacrifice had been light for so strong a man, once he forced himself to make it.

Last night—secure in his impregnable self-trust—he had broken his inviolable rule. As a result he had become a laughing-stock for the people whose favor he so unspeakably desired to win. As to his own adherents, he gave their possible opinions not one thought. Whatever the Boss said “went” with them. Had he declared himself a candidate for holy orders, or blurted out the innermost secrets of the “machine,” they would probably have believed he was acting for the best. But those others——!

She was very pretty and dainty and young, in her simple white morning frock.

And, over and above all, his declaration of candidacy for Governor——

A knock at the door of his study broke in on the audible groan of self-contempt this last and ever-recurrent thought wrung from his tight lips. Caleb stopped midway down the room, his short red hair bristling with fury at the interruption.

“What do you want?” he snarled.

The door opened and Anice Lanier came in. She was very pretty and dainty and young, in her simple white morning frock. She carried a set of tablets whereon it was her custom to transcribe notes of Caleb’s morning instructions for reference or for later amplification by his two stenographers.

“Well!” roared Conover, glowering across the room at her, “what in hell do you want?”

“To tender my resignation,” was the unruffled reply.

“Your what?” he gasped, stupidly.

“My resignation,” in the same level, impersonal tones. “To take effect at once. Good morning.”

She was half-way out of the room before her employer could hurry after and detain her.

“What’s—what’s the meaning of this?” asked Caleb, the brutal belligerency trailing out of his voice. Then, before she could answer, he added: “Because I spoke like that just now? Was that it? Because I said—And you’d throw over a good job just because of a few cranky words? Yes, I believe you would. You’d do it. It isn’t a bluff. Maybe that’s why you make such a hit with me, Miss Lanier. You’re not scared every time I open my mouth. And you stand up for yourself.”

He eyed her in a quizzically admiring fashion, as one might a beautiful but unclassified natural history specimen. She made no reply, but stood waiting in patience for him to move from between her and the door.

Caleb grinned.

“Want me to apologize, I s’pose?” he grumbled.

“A gentleman would not wait to ask.”

“Maybe you think a gentleman wouldn’t of said what I did, in the first place, eh?”

“Yes, I do think so. Don’t you?”

“Well, I’m sorry. Let it go at that. Now let’s get to work. Say”—as they moved across to their wonted places at the big centre table, “you oughtn’t to take offence at anything about me this morning. You must know how sore I am.”

“What’s the matter?”

“As if you didn’t know! You saw how many kinds of a wall-eyed fool I made of myself last night. Isn’t that enough to make a man sore? And to think of it being taken down by those newspaper idiots and printed all over the country!”

He gave the nearby chair a kick, avalanching the morning papers to the floor.

“Have you read those?” queried Anice.

“No. Why should I rub it in? I know what they——”

“Why not look at them before you lose your temper?”

Caleb snatched up the Star, foremost journal of Granite. He glanced down the last column of the front page, and over to the second.

“Here’s the story of the show just as we dictated it beforehand,” he commented. “List of guests—Where in thunder is that measly speech? Have they given it a column to itself? Oh—way down at the bottom. ‘In a singularly happy little informal address at the close of the evening Mr. Conover mentioned his forthcoming candidacy for governor.’ Is that all any of them have got about it?”

“They have your pledge to run for Governor blazoned over two columns of the front page of nearly all the papers. But nothing more about the speech itself.”

“But how——”

“I took the liberty of stopping the reporters before they left the house, and telling them it would be against your wish for any of your other remarks to be quoted.”

“You did that? Miss Lanier, you’re fine! You’ve saved me a guying in every out-of-State paper in the East. I want to show my appreciation——”

“If that means another offer to raise my salary, I am very much obliged. But, as I’ve told you several times before, I can’t accept it. Thank you just the same.”

“But why not? I can afford——”

“But I can’t. Don’t let’s talk of it, please.”

“And every other soul in my employ spraining his brain to plan for a raise! The man who understands women—if he’s ever born—won’t need to read his Bible, for there’ll be nothing that even the Almighty can teach him.”

“Shan’t we begin work? About this Fournier matter. He refuses to pay the $30,000, and we can’t even get him to admit he owes it. Shall I——”

“Write and tell him unless he pays that $41,596 within thirty days——”

“But it’s $30,000, not $41,000. He——”

“I know that. And he’ll write us so by return mail. That’ll give us the acknowledgment we want of the $30,000 debt. What next?”

“The Curtis-Bayne people of Hadley are falling behind on their contract with the C. G. & X.”

“I guess they are,” chuckled Caleb. “They’re beginning to see a great light, just as I figured out. Well, let ’em squirm a bit.”

“But the contract—you may remember Mr. Curtis asked to look at our copy of it when he was in Granite. He said he wanted to verify a clause he couldn’t quite recollect. You told me to send it to him, and I did.”

“Yes, I remember.”

“Well, he never returned it. And this morning we get this letter from him: ‘In regard to your favor of the 9th inst., in which you speak of a contract, we beg to state you must have confused us with some other of your road’s customers. The Curtis-Bayne Company has no contract with the C. G. & X., and can find no record of one. If you have such a document kindly produce it.’”

“Well, well, well!” gurgled Caleb. “To think how that wicked old Curtis fox has imposed on my trust in human nature! He’s got us, eh?”

“It looks so, I’m afraid.”

“Looks so to him, too. It’ll keep on looking so till I shove him into court and make him swear on the witness stand that no contract ever existed. Then it’ll be time enough to produce the certified copy I had made just after I got his request to send the original to his hotel. Poor old Curtis! Please write him a very blustering, scared, appealing kind of letter. Next?”

“O’Flaherty’s sent another begging note, about that claim of his against the road. It begins: ‘Dear Mr. Conover: As you know, I’ve seen better days’——”

“Tell him I can’t be held accountable for the weather. And—say, Miss Lanier, let all the rest of this routine go over for to-day. I’ve a bigger game on, and I’ve got to hustle. That Governorship business——”

“Yes?”

“That was the foolest thing I ever did. It seemed to me at the minute a grand idea as a wind-up for my crazy speech. But I guess I’ll have to pay my way all right before I’m done with last evening. The free list’s suspended as far’s I’m concerned.”

“You mean there’s some doubt of your getting the nomination?” she asked, a sudden hope making her big eyes lustrous.

“Doubt? Doubt? Say, I thought you knew me better than that. Why, the nomination’s right in front of me on a silver salver and trimmed with blue ribbons. And the election, too, for that matter.”

“Then”—the hope dying—“why do you speak as you did just now?”

“It’s this way: I’ve held Granite and the Mountain State by the nape of the neck for ten years. I’m the Boss. And when I give the word folks come to heel. But all this time I’ve been standing in the background while I pulled the strings. It was safer that way and pleasanter. I’d a lot rather write the play than be just a paid actor in it. But now I’ve got to jump out of my corner in the wings and take the centre of the stage. There’s a lot more glory on the stage than in the wings, but there’s lots more bad eggs and decayed fruit drifting in that direction, too. If the audience don’t like the actor they hiss him. The man in the wings don’t get any of that. All he has to do is to call off that actor and put on another the crowd’ll like better, or maybe a new play if it comes to the worst.

“But here I’m to take the stage and get the limelight and the newspaper roasts—outside the State—and not an actor can I shunt it off on. That’s why I’ve never took public office since I was Mayor. And then it was only a stepping-stone to the Leadership. Now I’ve got to leave the background and pose in the Capitol. There’s nothing in it for me, except a better social position. That’s a lot, I know. But I’m not so sure that even such a raise is worth the price.”

“Then why not withdraw?”

“Not me! Withdraw, and be laughed at by my own crowd as well as the society click? It’d smash me forever. It’s human nature to love a criminal and to hate a four-flusher. And cold feet ain’t good for the circulation of the body politic. It’s apt to end by freezing its possessor out. No, sir! I’m in it, and I got to swim strong. The nomination and the election’s easy enough. But just a ‘won handily’ won’t fill the bill. I’ve got to sweep the State with the all-firedest landslide ever slidden since U. S. Grant ran around the track twice before Horace Greeley got on speaking terms with his own stride. It’s got to be a case of ‘the all-popular Governor Conover.’ I’ve got to go in on the shoulders of that rampant steed they call ‘The Hoorah!’ That’ll settle forever any doubts of my fitness, and it’ll stop all laughs at what I said last night. When a man’s the people’s unanimous choice, the few stray knocks that happen at intervals do him more good than harm. But if it was just touch-and-go, everybody’d be screeching about fraud and boss rule winning over honest effort. These Civic Leaguers are too noisy, as it is. I’ve got to start in right away.”

“Any orders?”

“Yes. When you go down stairs, please send for Shevlin and Bourke and Raynor and the rest on this list, and telephone the editors I’d like to see ’em this afternoon. I’ll have the ball rolling by night. Say, Miss Lanier, the campaign’ll mean extra work for you. I want to make it worth your while. Come now, don’t be silly. Let me make your salary——”

“I beg you won’t speak of that any more. I cannot accept a raise of salary from you.”

“But why not? You earn more and——”

“I earn all I get. And, as I’ve told you before, my reasons for accepting no larger stipend than you offered publicly for a governess for Blanche three years ago, are my own. I consider them good. I am glad to get the money I do. I believe I more than earn it. But I can accept no more, and I can take no presents nor favors of any sort from you. I can’t explain to you my reasons. But I believe they are good.”

“But it’s so absurd! I——”

“Have you ever found me shirking my work or disloyal in any way to your interests, on account of the smallness of my salary? I have handled business and political secrets of yours that would have involved millions in loss to you if I had betrayed you. I have been loyal to those interests. I have done your work satisfactorily. I could have done no more on three times my pay. There let the matter rest, please.”

“Just as you like!” grumbled Conover. “Lord! how the crowd’d stare if it heard Caleb Conover teasing anyone to take more of his money!”

“Money won’t buy everything.”

“No? Well, it gives a pretty big assortment to choose from. And——”

The door was flung unceremoniously open, and Gerald slouched in, his pasty face unwontedly sallow from last night’s potations. For, with a few of the mushroom crop of the jeunesse dorée of Granite, he had prolonged the supper-room revels after the departure of the other guests.

“Hello, Dad!” he observed. “Thought I’d find you alone.”

Caleb, his initial ill-temper softened by his talk with Anice, greeted his favorite child with a friendly nod.

“Sit down,” he said. “I’ll be at leisure in a few moments. And, say, throw that measly blend of burnt paper and Egyptian sweepings out of the window. Why a grown man can’t smoke man’s-sized tobacco is more’n I can see.”

The lad, with sulky obedience, tossed away the cigarette and came back to the table.

“Hear the news?” he asked. “It seems you’ve got a rival for the nomination.”

“Hey?”

“Grandin was telling me about it last night. His father’s one of the big guns in the Civic League, you know. It seems the League’s planning to spring Clive Standish on the convention.”

“Clive Standish? That kid? For governor? Lord!”

“Good joke, isn’t it? I——”

“Joke? No!” shouted Caleb. “It’s just the thing I wouldn’t have had happen for a fortune. He’s poor, but he belongs to the oldest family in the State, and his blood so blue you could use it to starch clothes with. Just the sort of a visionary young fool a lot of cranks will gather around. He’ll yell so loud about the ‘people’s sacred rights’ and ‘ring rule’ and all that rot, that they’ll hear him clear over in the other States. And when they do, the out-of-State papers will all get to hammering me again. And the very crowd I’m trying to score with, by running for Governor, will vote for him to a man. He’s one of them.”

“So you think he has a chance of winning?” asked Anice.

“Not a ghost of a chance. He’ll die in the convention—if he ever reaches that far. But it will stir up just the opposition I’ve been telling you I was afraid of. Well, if it meant work before, it means a twenty-five-hour-a-day hustle now. I wish you’d telephone Shevlin and the others, please, Miss Lanier. Tell ’em to be here in an hour.”

As the girl left the room, Caleb swung about to face his son. The glow of coming battle was in his face.

“Now’s your chance, Jerry!” he began, hot with an enthusiasm that failed to find the faintest reflection in the sallow countenance before him. “Now’s your chance to get back at the old man for a few of the things he’s done for you.”

“I—I don’t catch your meaning,” muttered Gerald, uncomfortably.

“You’ve got a sort of pull with a certain set of young addlepates here, because you live in New York and get your name in the papers, and because you’ve a dollar allowance to every penny of theirs: I want you to use that pull. I want you should jump right in and begin working for me. Why, you ought to round up a hundred votes in the Pompton Club alone, to say nothing of the youngsters on the fringe outside, who’ll be tickled to death at having a feller of your means and position notice ’em. Yes, you can be a whole lot of help to me this next few weeks. Take off your coat and wade in! And when we win——”

“Hold on a moment, Dad!” interrupted Gerald, whose lengthening face had passed unnoted by the excited elder man. “Hold on, please. You mean you want me to work for you in the campaign for Governor?”

“Jerry, you’ll get almost human one of these days if you let your intelligence take flights like that. Yes, I——”

“Because,” pursued Gerald, who was far too accustomed to this form of sarcasm from his father to allow it to ruffle him, “because I can’t.”

“You—you—what?” grunted Caleb, incredulously.

“I can’t stay here in Granite all that time. I—I must get back to New York this week. I’ve important business there.”

“Well, I’ll be—” gasped Conover, finding his voice at last, and with it the grim satire he loved to lavish on this son, so unlike himself. “Business, eh? ‘Important business!’ Some restaurant waiter you’ve got an appointment to thrash at 2.45 A.M. on Tuesday, or a hotel window you’ve made a date to drive through in a hansom? From all I’ve read or heard of your life there, those were the two most important pieces of business you ever transacted in New York. And it was my money paid the fines both times. No, no, Sonny, your ‘important business’ will keep, I guess, till after November. Anyhow, in the meantime you’ll stay right here and help Papa. See? Otherwise you’ll go to New York on foot, and have the pleasure of living on what the three-ball specialists will give you for your hardware. No work, no pennies, Jerry. Understand that? Now go and think it over. Papa’s too busy to play with little boys to-day.”

To Caleb’s secret delight he saw he had at last roused a spark of spirit in the lad.

“My business in New York,” retorted Gerald hotly, “is not with waiters or hotels. It is with my wife.”

Caleb sat down very hard.

“Your—your—” he sputtered apoplectically.

“My wife,” returned the youth, a sheepish pride in look and words. “It was that I came up here to speak to you about this morning. You were so busy yesterday when I got to town that——”

“Are you going to tell me about this thing, or have I got to shake it out of you?”

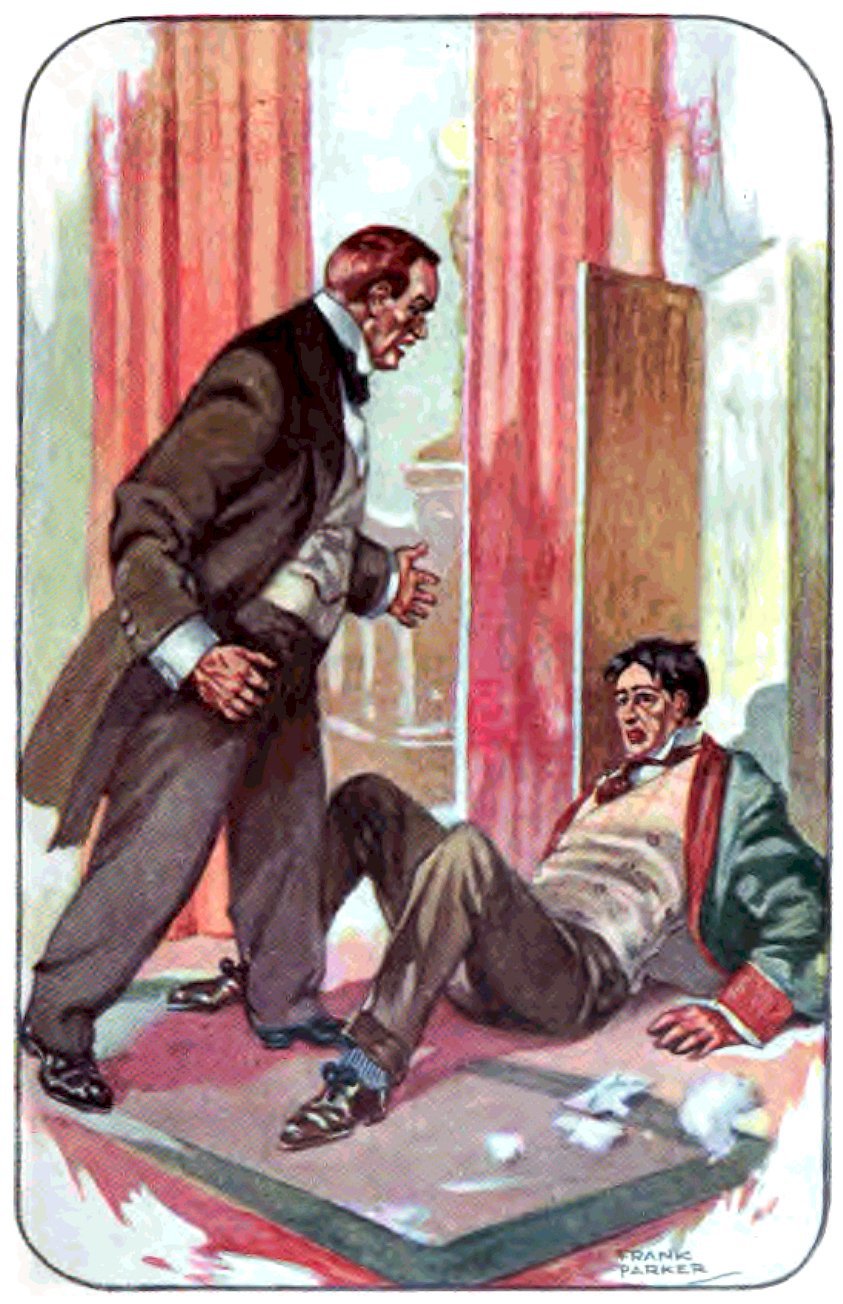

“Jerry, you ass! Are you crazy or only drunk?”

“Father,” protested Gerald with a petulance that only half hid his growing nervousness, “I do wish you’d call me ‘Gerald,’ and drop that wretched nickname. If——”

He got no further. Conover was upon him, his tough, knotty hands gripping the youngster’s shoulders and shaking him to and fro with a force that set Gerald’s teeth clicking.

“Now then!” bellowed the Railroader, mighty, masterful, terrible as he let the breathless lad slide to the floor and towered wrathful above him. “Are you going to tell me about this thing, or have I got to shake it out of you? Speak up!”

Gulping, panting, all the spirit momentarily buffeted out of him, Gerald Conover lay staring stupidly up at the angry man.

“I’m—I’m married!” he bleated. “I—I meant to tell you when——”

“Who to?” demanded Caleb in an agony of self-control.

“Miss Enid Montmorency. She——”

“Who is she?”

“She is—she’s my wife. Two months ago we——”

“Who is she? Is she in society?”

“Her family were very famous before the war. She——”

“Is she in good New York society?”

“She—she had to earn her own living and——”

“And what?”

“She—I met her at Rector’s first. Her company——”

“Great Lord!”

The words came like a thunderclap. Caleb Conover stepped back to the wall, his florid face gray.

“You MARRIED a chorus girl?”

“She—her family before the war——”

Caleb had himself in hand.

“Get up!” he ordered. “You haven’t money enough nor earning power enough to buy those boards you’re sprawling on. Yet you saddle yourself with a wife—a wife you can’t support. A woman who will down all your social hopes. And mine. You let a designing doll with a painted face dupe you into——”

“You shan’t speak that way of Enid!” flared up the boy, tearfully. “She is as good and pure as——”

“As you are. And with a damned sight more sense. For she knows a legal way of grabbing onto a livelihood; and you don’t. Shut up! If you try any novel-hero airs on me, you young skunk, I’ll break you over my knee. Now you’ll stand still and you’ll listen to what I have to say.”

Gerald, cowed, but snarling under his breath, obeyed.

“I won’t waste breath telling you all I’d hoped for you,” began Conover, “or how I tried to give you all I missed in my own boyhood. You haven’t the brains to understand—or care. What I’ve got to say is all about money. And I never found you too stupid to listen to that. You’ve cut your throat. Nothing can mend that. We’ll talk about the future at another time. It’s the present we’ve got to ’tend to now. You’re going to be of some use to me at last. The only use you ever will be to anyone. Your allowance, for a few months, is going on just the same as before. But you’ve got to earn it. And you’re going to earn it by staying right here in Granite, and working like a dog for me in this campaign. If you stir out of this town, or if your—that woman comes here, or if you don’t use your pull in my behalf with the sap-heads you travel with at the Pompton Club—if you don’t do all this, I say, till further orders—then, for now and all time, you’ll earn your own way. For you’ll not get another nickel out of me. I guess you know me well enough to understand I’ll go by what I say. Take your choice. You’ve got an earning ability of about $4 a week. You’ve got an allowance of $48,000 a year. Now, till after election, which’ll it be?”

Father and son faced each other in silence for a full minute. Then the latter’s eyes fell.

“I’ll stay!” he muttered.

“I thought so. Now chase! I’m busy.”

Gerald slouched to the door. On the threshold he turned and shook his fist in impotent fury at the broad back turned on him.

“I’ll stay!” he repeated, his voice scaling an octave and breaking in a hysterical sob, “I’ll stay! But, before God, I’ll find a way to pay you off for this before the campaign is over.”

Caleb did not turn at the threat nor at the loud-slamming door. He was scribbling a telegram to his New York lawyer.

“Gerald in scrape with chorus girl, Enid Montmorency,” he wrote. “Find her and buy her off. Go as high as $100,000.”

“Father Healy says, ‘The sins of the fathers shall be visited on the children,’” he quoted half-aloud as he finished; “but when they are visited in the shape of blithering idiocy, it seems ’most like a breach of contract.”

The Railroader was not fated to enjoy even the scant privilege of solitude. He had hardly seated himself at his desk when the sacred door was once more assailed by inquisitive knuckles.

“The Boys haven’t wasted much time,” he thought as he growled permission to enter.

The tall, exquisitely-groomed figure of his new son-in-law, the Prince d’Antri, blocked the threshold. With him was Blanche.

“Do we intrude?” asked d’Antri, blandly, as he ushered his wife through the doorway and placed a chair for her. Caleb watched him without reply. The multifarious branches of social usage always affected him with contemptuous hopelessness. He saw no sense in them; but neither, as he confessed disgustedly to himself, could he, even if he chose, possibly acquire them.

“We don’t intrude, I hope,” repeated the prince, closing the door behind him, and sitting down near the littered centre table.

“Keep on hoping!” vouchsafed Conover gruffly. “What am I to do for you?”

He could never grow accustomed to this foreign son-in-law whom he had known but two days. Obedient, for once, to his wife, and to his daughter’s written instructions, he had yielded to the marriage, had consented to its performance at the American Embassy at Paris rather than at the white marble Pompton Avenue “Mausoleum,” and had readily allowed himself to be convinced that the union meant a social stride for the entire family such as could never otherwise have been attained.

His wife and daughter had returned from Europe just before the reception (whose details had, by his own command, been left wholly to Caleb), bringing with them the happy bridegroom. Caleb had never before seen a prince. In his youth, fairy tales had not been his portion; so he had not even the average child’s conception of a mediæval Being in gold-spangled doublet and hose, to guide him. Hence his ideas had been more than shadowy. What he had seen was a very tall, very slender, very handsome personage, whose costumes and manner a keener judge of fashion would have decided were on a par with the princely command of English: perfect, but a trifle too carefully accentuated to appeal to Yankee tastes.

Beyond the most casual intercourse and table talk there had been hitherto no scope for closer acquaintanceship between the two men. The reception had taken up everyone’s time and thoughts. Caleb had, however, studied the prince from afar, and had sought to apply to him some of the numberless classifications in which he was so unerringly wont to place his fellow-men. But none of the ready-made moulds seemed to fit the newcomer.

“What can I do for you?” repeated Conover, looking at his watch. “In a few minutes I’m expecting some——”

“We shall not detain you long. We have come to speak to you on a—a rather delicate theme.”

“Delicate?” muttered Caleb, glancing up from the politely embarrassed prince to his daughter. “Well, speak it out, then. The best treatment for delicate things is a little healthy exposure. What is it?”

“I ventured to interrupt your labors,” said d’Antri, his face reflecting a gentle look of pain at his host’s brusqueness, “to speak to you in reference to your daughter’s dot.”

“Her which?” queried Caleb, looking at the bride as though in search of symptoms of some violent, unsuspected malady.

“Amadeo means my dowry,” explained Blanche, with some impatience. “It is the custom, you know, on the Continent.”

“Not on any part of the Continent I ever struck. And I’ve been pretty much all over it from ’Frisco to Quebec. It’s a new one on me.”

“In Europe,” said Blanche, tapping her foot, and gazing apologetically at her handsome husband, “it is customary—as I thought everybody knew—for girls to bring their husbands a marriage portion. How much are you going to settle on me?”

“How much what? Money? You’ve always had your $25,000 a year allowance, and I’ve never kicked when you overdrew it. But now you’re m