CHAPTER V.

THE GYPSY PARTY.

ONE Wednesday evening, in summer, Royal and Lucy were sitting on the front door steps, eating bread and milk, which their mother had given them for supper, when they saw a boy coming along the road, with a little letter in his hand.

“There comes a boy with a letter,” said Royal. “I wonder whether he is going to bring it here for my father.”

The boy walked along, and, when he reached the front gate, he opened it, came up, and handed the note to Royal. “There’s a letter for you.” Then he turned round, and went away again.

Royal looked at the outside of the note, and saw that his own name and Lucy’s were written there. He accordingly opened it, and read as follows:—

“Mary Jay sends her compliments to Royal and Lucy, and would be happy to have their company at a gypsy party, at her house, to-morrow, at 3 o’clock.

“Wednesday Morning.”

“A gypsy party! I wonder what a gypsy party is,” said Lucy.

“It is a party to have a supper out of doors,” said Royal. “We’ll go, Lucy; we’ll certainly go. I should like to see a gypsy supper.”

“Yes,” said Lucy, “if mother will let us. I’ll go directly and ask her.”

Lucy went and showed her note to her mother. Her mother seemed much pleased with it, and she said that Lucy might go.

“And Royal too?” asked Lucy.

“Why,—yes,” said her mother, with some hesitation. “I suppose that I must let Royal go, since he is invited; but it is rather dangerous to admit boys to such parties.”

“Why, mother?” said Lucy.

“Because,” replied her mother, “boys are more rough in their plays than girls, and they are very apt to be rude and noisy.”

Lucy went back to the door, and told Royal that their mother said that they might go.

“But she thinks,” added Lucy, “that perhaps you will be noisy.”

“O no,” said Royal, “I will be as still as a mouse.”

Just then, Royal and Lucy saw a little girl, dressed very neatly, walking along towards their house. As she came nearer, Lucy saw it was Marielle, her old playmate at the school where Lucy first became acquainted with Mary Jay. Marielle advanced towards the house, looking at Lucy with a very pleasant smile. Royal went and opened the gate for her.

“How do you do, Lucy?” said Marielle.

Lucy did not answer, but looked at Marielle with an expression of satisfaction and pleasure upon her countenance.

“Are you going to Mary Jay’s gypsy party to-morrow?” she asked.

“Yes, and Royal too,” replied Lucy. “Are you going?”

“Yes, I am going, and Harriet, and Jane, and Laura Jones, and little Charlotte, and one or two others. My brother is going, too, and William Jones. And we are all going to carry something in baskets to eat.”

“Why, what is that for?” asked Royal.

“Why, you see,” she replied, “Mary Jay is going away in two or three days, and is not coming back for a year; and so she invited us to come and pay her a farewell visit,—all of us that she used to teach in the school. And my mother thought that, as she was going away so soon, she must be very busy; and so she sent me to go and ask her not to make any preparation herself, but to let us all bring things in our baskets; and then she could put them on the table and arrange them after we got there.”

“And what did she say?” asked Lucy.

“Why, she laughed, and said it was a funny way to give a party, to have the guests bring their suppers with them. But, then, pretty soon she said that we might do so; and she told me to say to my mother that she was very much obliged to her indeed.”

“Well,” said Royal, “let’s go in and tell mother about it.”

So the children went in and told their mother, and she said that she thought it was an excellent plan, and that she would give them a pie and some cake, and a good bottle of milk, for their share.

“My mother,” said Marielle, “wanted me to ask you not to send a great deal.”

“Well, that will not be sending a great deal; besides, what would be the harm if I should?”

“Why, she says that generally, in such cases, they carry too much.”

“Yes,” said Royal’s father, who was then sitting in the room reading. “When people form a party to go up a mountain, they each generally take provisions enough for themselves and all the rest of the party besides; so that they have to lug it all up to the top of the mountain, and then to lug it down again.”

They all laughed at this; and Royal’s father went on with his reading. His mother then said that she would not send a great deal, and Marielle bade Lucy and Royal good evening, and went home. The next day, at three o’clock, there were quite a number of children walking along the road towards Mary Jay’s house, all with small baskets in their hands.

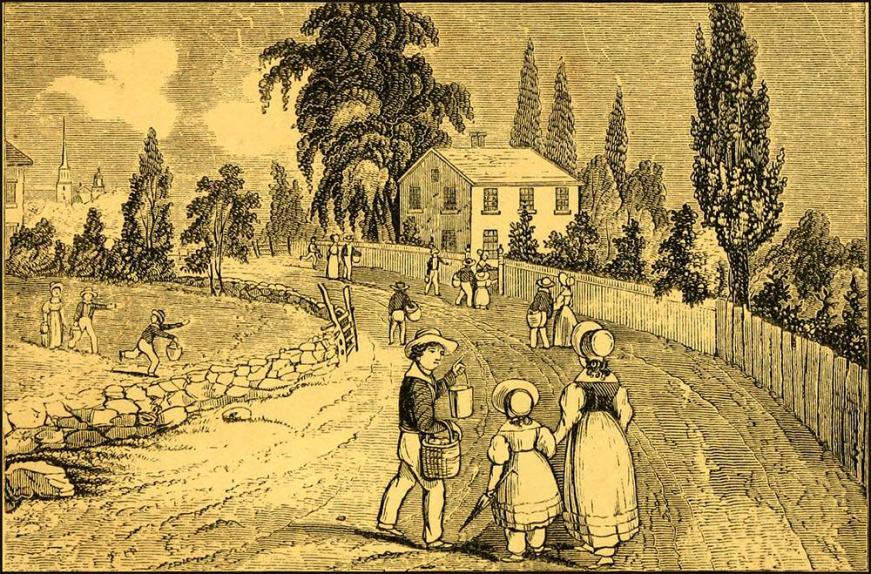

Royal, Lucy, and Marielle, went together; and, as they reached the house, they found a boy in the yard, who told them that Mary Jay was at her seat down beyond the garden. So they went through the garden, and thence over into the walk which led down through the trees, as described in LUCY AT STUDY.

“Royal, Lucy, and Marielle, went together.”—

As they drew near the place where they were to come in sight of the little pond of water, they heard the sound of voices; and, after a few steps more, they caught a glimpse of something white through the trees. They walked on, and presently they came in sight of a pretty long table, just beyond the pond, upon a flat piece of grass ground, up a little from the pond, and under the trees. The table was surrounded with girls moving about in all directions. Some were opening their baskets, some were hanging up their bonnets upon the branches of the trees, and several were standing around Mary Jay, who was seated at the head of the table, upon a chair, with her feet upon a small cricket, and a crutch lying down by her side.

“O, there they are,” said Lucy, as soon as she saw them; and she began to run. Royal followed, carrying the provisions.

“Ah, Royal,” said Mary Jay, “I am glad you have come; for I want you to help William make us a fireplace to roast our apples and corn. It would not be a gypsy supper without some cooking.”

“A fireplace?” said Royal; “I don’t know how to make a fireplace.”

“O, it is only a gypsy fireplace,” replied Mary Jay; “and that is very easy to make. All you have to do is to cut two crotched sticks, and drive them down into the ground, about as far apart as you can reach; and then cut a green pole, and lay across from one to the other. Then we can build our fire upon one side, and stand up our ears of corn against the pole, on the other; and so they will roast. Only we must turn them.”

“Well,” said Royal; “but where shall I get an axe?”

“You will have to go up to the house and get the axe. You will find one in the shed, just beyond the water post.”

So Royal and William went off after the axe, while the girls were all busy, some about the table, taking out the various stores and arranging them; others rambling about in the paths around, looking at Mary Jay’s stone seat, or playing with the pebble-stones on the margin of the water.

In a short time, Royal returned; and he and William began to look around, among the small trees, for two with branches which would form a crotch.

“Here is one, Royal,” said a gentle voice, at a little distance through the trees.

Royal turned, and saw that Marielle had found one for him. He went to it, to look at it.

“Will that do?” said she.

“Yes, indeed,” said Royal; “it is a beautiful crotch.”

In fact, it did look very beautiful and regular. The two branches diverged equally from the main stem below, so as to give the fork a very symmetrical form. Royal cut it down. Then he cut off the main stem about a foot from the crotch, and then the two branches a few inches above. He carried it to Mary Jay, to show her what a beautiful crotch he had got, for one.

“And now,” said he, “where shall we make our fireplace?”

“O, any where about here, where there is a level place; you and William can find a place. Marielle may help you.”

So they began to look about for a place. They found a very good place near the brook, and not very far from the table. Royal began to drive down the crotch. But here he soon found difficulty. The two branches of the fork diverged equally from the main stem, and of course, when the point was set into the ground, neither of them was directly over it; so that, when Royal struck upon one of them, the tendency of the blow was to beat the stake over upon one side, and if he struck upon the other branch, it beat it over upon the other side. In a word, it would not drive.

“Strike right in the middle of the crotch,” said William.

Royal did so. This seemed to do better at first; but the axe did not strike fair, as the head of it, in this case, went down into the wedge-shaped cavity between the branches, instead of finding any solid resistance to fall upon. And after a few blows, the branches were split asunder by the force of the axe wedging itself between them; and there was, of course, an end of the business.

“O dear me!” said Royal, with a long sigh, as he stopped from his work, and leaned upon his axe.

As he looked up, he saw an old man, on the other side of the brook, with a sickle in his hand, who had been down in a field at his work, and who was now returning. He had seen Royal driving the stake as he was passing along.

“The trouble is, boy,” said the old man, “that you have not got the right sort of crotch. The arms of it branch off both sides.”

“I thought it was better for that,” said Royal.

“No,” said the man; “it looks better, perhaps, but it won’t drive. Get one where the main stem grows up straight, and the crotch is made by a branch which grows out all on one side. Then you can drive on the top of the main stem.”

“O yes,” said Royal, “I see.”

“Besides,” said the old man, “if that is the place that you have chosen for your fire, I don’t think that it is a very good one.”

“Why not?” said Royal.

“Why, the smoke,” replied the old man, “will drift right down upon the tables. It is generally best to make smokes to leeward.”

So saying, the old man turned around, and walked slowly away.

“What does he mean by making smokes to leeward?” asked a little girl who was standing near. It was Charlotte.

“I know,” said Royal; “let us see,—which way is the wind?” And he began to look around upon the trees, to see which way the wind was blowing.

“Yes, I see,” he added. “It blows from here directly towards the table; we should have smoked them all out. We must go around to the other side of the brook, and then the smoke will be blown away. But first we must go, William, and get some more crotched stakes.”

So Royal and William went looking about after more stakes. They tried to find them of such a character as the old man had described; and this was easy; for it was much more common for a single branch to grow off upon one side, leaving the main stem to go up straight, than for such a fork to be produced as Marielle had found. Marielle seemed to be sorry that her fork had proved so unsuitable; but Royal told her that it was no matter. He said that hers was a great deal handsomer than the others, at any rate, although it would not drive.

They found suitable crotches very easily, and drove them into the ground. Then they cut a pole, and laid it across, and afterwards built a fire upon one side of it; and by the time that the other preparations were ready for their supper they had a good hot fire, and were ready to put the ears of corn down to roast.

The children had a very fine time eating their supper. Some stood at the table; and some carried their cakes and their blueberries away, and sat, two or three together, under the trees, or on the rocks. Lucy went to Mary Jay’s seat, and took possession of that. They made little conical cups of large maple leaves, which they formed by bringing the two wings of the leaf together and pinning them; and then the stem served as a little handle below. They were large enough to hold two or three spoonfuls of blueberries.

They had milk to drink too, and water, which they got from a spring not far from Mary Jay’s seat. Lucy went there to get some water; and, as she was coming back to her seat, bringing it carefully, she saw Royal doing something on the shore of the little pond. She put down her mug, and went to see.

He was making a vessel of a small piece of board. He had a large leaf fastened up for a sail. He secured the leaf, by making a slender mast, and running this mast through the leaf, in and out, as you do with a needle in sewing; and then, leaving the leaf upon the mast, he stuck the end of the mast into the board. Then he loaded his vessel with a cake, and some blueberries, and said that he was going to send it over to the other side, to Charlotte, who was waiting there to receive it. The children all gathered around to see it sail. It went across very beautifully, and Charlotte ate the cargo.

Then they brought the ship round back again, to load it again; and at this time, when it was nearly loaded with other things, Marielle brought the saucer of an acorn which she had gathered from a neighboring tree, and filled it with milk, and then set it carefully upon the stern of the vessel. She said that she wanted Charlotte to have something to drink. But just before they got ready to sail the vessel, they heard a little bell ring at the table, which they all understood at once to be a summons from Mary Jay to them to go there, and attend to what she had to say to them.

So those who were at the water left it at once, and the others came in from the places where they were playing; and all gathered around the table.

“Now, children,” said Mary Jay, “we’ll clear away the table, and then you will have an hour and a half to play before it will be time to go home. First, put all the fragments carefully into the large basket under the table.”

The children looked under the table, and saw a good-sized basket there; and they took all that was left upon the table, and put it carefully in. Then Mary Jay told them to fold up the cloth, and put that in; and they did it. Then William and Royal took the board which formed the table, and carried it up towards the house, and stood it up by the stile at the foot of the garden; the other children carried the basket which was under the table, and the cloth, and all the other baskets, and put them down, in regular order, near the same place. When the children came back, they found that Mary Jay had moved to her stone seat, where she sat waiting for them.

“Now,” said Mary Jay, “the things are all ready to be carried home, and the ground is clear for our plays.”

“What shall we play?” said several voices.

“We’ll see presently,” said Mary Jay, “when you get ready.”

So the children all collected around Mary Jay, some standing and some sitting in various places, upon the flat stones.

“Now,” said Mary Jay, “how many are there here? One, two, three,”—and so she went on counting until she ascertained the number. There were ten.

“There are ten; that will be about eight minutes apiece. Each of you may choose a play for eight minutes. First you may mention any plays that you would like,—so that you may all have a good number in mind to choose from.”

One of the girls said, “Blind man’s buff;” another, “A march;” another, “Hunt the stag;” and several other plays were named.

“Now,” said Mary Jay, “I will call upon one of the oldest children to choose a play. Laura, what should you like for your eight minutes?”

“A march,” said Laura.

“Yes,” said all the children, “let’s have a march.”

“Would any of the rest of you,” said Mary Jay, “like to have your eight minutes added to Laura’s? and that will make sixteen minutes for a march.”

“Yes, I,” and “I,” said several voices.

“But then you must remember,” said Mary Jay, “that whoever gives up her eight minutes to a march, cannot choose any other play for it.”

“O, well, then I don’t want to give mine,” said one of the girls, “for I want to have Blind-man’s-buff for mine.”

However, there was one of the girls who decided to add her eight minutes to Laura’s for the march; and so, at Mary Jay’s command, they all formed a line, and marched about under the trees for quarter of an hour. Mary Jay appointed Royal to be the captain; and so they all followed him around and under the trees, singing a merry song all the way. They had branches of the trees for banners.

When the march was over, Mary Jay called for more plays, and they played three more times, about eight minutes each, as near as Mary Jay could estimate the time.

“But, Mary Jay,” said Royal, “you have passed by Marielle; and she is older than the others that you have called upon.”

“So I have,” said Mary Jay. “Marielle, I did not mean to forget you.”

“O, it’s no matter,” said Marielle.

“Well, what play should you like? You shall take your turn now.”

“Cannot we choose any thing besides plays?” asked Marielle.

“Why, yes,” replied Mary Jay, “perhaps so; I’ll see. What should you like?”

Marielle looked down, and appeared half afraid to say what she wished; but presently she said,—

“Why, if you would be kind enough to read us a story out of your Morocco Book.”

“O yes,” “Yes,” exclaimed all the children, “let us have a story out of the Morocco Book.”

“Very well,” said Mary Jay; “I have no objection. I can find a short one, which will not take more than eight minutes.”

But the children did not want a short one, and those who had not chosen plays agreed to appropriate all their time to the Morocco Book.