CHAPTER II.

METAPHYSICS.

NOTWITHSTANDING their father’s recommendation of the name convalescent box, the children continued to call it the marble box. Lucy said that that name was a great deal easier, and she thought it was prettier, besides. For some time after this, therefore, the children were accustomed to call it by one name, and the parents by the other. Whatever might be its name, however, it was found to answer a very excellent purpose. It continued to be used, according to the rules pasted upon its lid; and as, in consequence, it was not opened very often, and as new books and playthings were frequently put into it, it came to be a very valuable resource when the children were confined to the house by indisposition; so much so that Lucy’s mother said that she thought it would be an excellent plan for every family to have a convalescent box.

One time, when Lucy had been sick,—long after the convalescent box was made, and in fact, after it had been used a great many times,—she carried a little cricket up to it, in the back entry, and sat down before it, and began to read. Royal had helped her first to move it out near a window. It was placed with one end towards the window, and the lid was turned back against a chair which she had placed behind it. She had also placed another chair before it, in such a way that, when she was sitting upon her cricket, she could lay her book in this chair, using it as a sort of table. When Royal had helped her move out the great box, he had gone down into the yard to play, leaving her to arrange the other things herself.

Accordingly, when they were all arranged, Lucy asked Royal if he would not come up and see her study.

“Yes,” said Royal, “I will come.”

So Royal went up stairs again, to see Lucy’s study, as she called it. He found her seated upon the cricket, with a picture-book open before her upon the chair.

“Well, Lucy,” said Royal, “I think you have got a very good study. What are you reading?”

“I am reading stories,” answered Lucy.

“What stories?” said Royal.

“One is about a parrot,” replied Lucy; “and there are some others which I am going to read after I have finished this.”

“But I think,” said Royal, “that you had better come down and play with me, behind the garden.”

The fact was, that Royal was going to make a little ship. He was going to work upon it at a seat in a shady place beyond the garden, and he wanted some company.

“Come, Lucy,” said he, “do go.”

“But I don’t think that mother will let me go out yet,” replied Lucy. “I have not got well enough to go out.”

“I’ll run and ask her,” said Royal.

Lucy called to him to stop, but he paid no attention to her call. She did not want to have him go and ask her mother; for, even if her mother would consent, she did not wish to go out. She did not assign the true reason. The true reason was, that she was interested in the story about a parrot, that could say, “Breakfast is ready; all come to breakfast,”—and she did not wish to leave it. Her fear that her mother would not allow her to go out was, therefore, not the true reason. It was a false reason.

People very often assign false reasons, instead of true ones, for what they do, or are going to do. But it is very unwise to do this. They very often get into difficulty by it. Lucy got into difficulty in this case; for, in a few minutes, Royal came back, and said that his mother sent her word that she might go out, if she chose, and stay one hour.

Thus the false reason which Lucy gave for not going with Royal, was taken away, and yet she did not want to go; but then she was embarrassed to know what to say next. That is the way that persons often get into difficulty by assigning reasons which are not the honest and true reasons; for the false reasons are sometimes unexpectedly removed out of the way, and then they are placed in a situation of embarrassment, not knowing what to say next. It is a great deal better not to give any reasons at all, than to give those which are not the ones which really influence us, but which we only invent to satisfy other persons.

When Royal told Lucy that her mother was willing to have her go out, she hesitated a moment, and then she said,—

“Well, Royal, if I go out now, I must shut and lock the marble box; and then we cannot open it again till the next time we are sick; and that may be a great while.”

“Well,” said Royal, “and suppose it is.”

“Why, then I shall have to wait a great while before I can hear the rest about the parrot.”

“O, never mind the parrot,” said Royal; “I will tell you some stories that will be prettier than that is, a great deal, I dare say.”

“What kind of a story will it be?” said Lucy.

“O, I don’t know,” answered Royal. “What sort of a story should you like?”

“I don’t know much about the different kinds,” said Lucy. “How many different kinds of stories are there?”

“Come with me,” replied Royal, “and I will tell you. I can tell you all about it, while I am making my ship.”

“But I wish you would tell me a little about it now,” said Lucy, “and then I can decide better whether to come or not.”

“Well,” said Royal, “there are three kinds of stories—true stories, probable stories, and extravagant stories.”

“Which is the best kind?” said Lucy. “I expect true stories.”

“Why, I don’t know,” said Royal. “If you will come with me, I will tell you one of each kind, and then you can judge for yourself.”

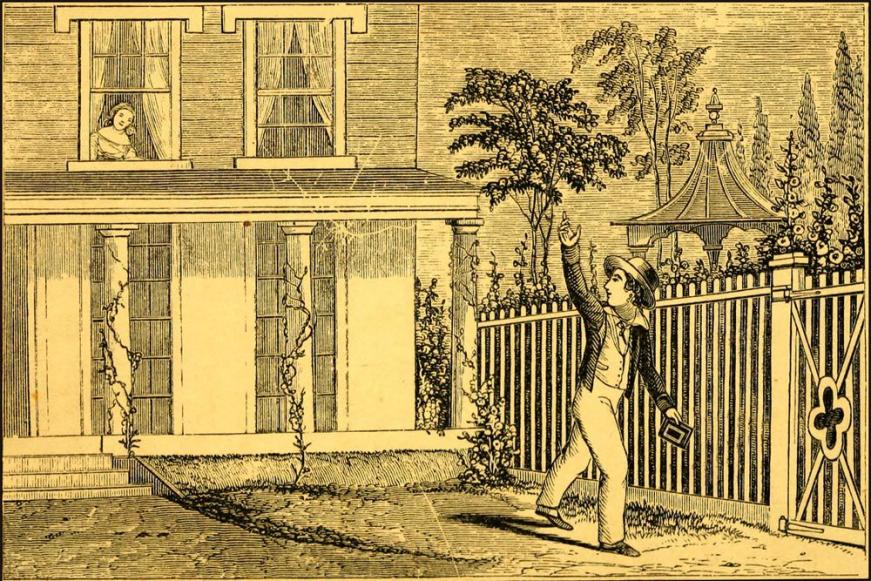

“She looked out at the window, and saw Royal walking along through the garden.”—

“Well, Royal,” said Lucy, as she saw that he was going away, “just tell me what sort of stories extravagant stories are.”

“Why, they are a very queer sort of stories indeed; you’ll know when you come to hear one.”

So saying, Royal went away, leaving Lucy in much perplexity of mind. She thought that she would just finish the story of the parrot, and that she would then go and hear Royal’s stories. But she could not read very fast, and her mind was distracted with wondering what sort of a story an extravagant story could be.

She looked out at the window, and saw Royal walking along through the garden. She wished very much that it was consistent with the rules of the marble box for her to go out and play with Royal an hour, and then come back and finish her story; but she knew that it was not.

Finally, her curiosity to hear the extravagant story triumphed, and she accordingly put the books away into the box, returned the till into its place, which she had taken out in order to gain more easy access to the books below, and then shut the lid and locked it. She was not strong enough to put the box back, where it belonged, without Royal; but she put away all the other furniture very carefully, and then went down stairs.

She carried the key to her mother, and said, “Here, mother, here is the key. I am going out to play with Royal. He is going to tell me an extravagant story.”

“An extravagant story!” repeated her mother, with some surprise; “what sort of a story is that?”

“I don’t know,” replied Lucy; “only Royal is going to tell me one.”

Her mother laughed, saying that she should like to hear one of Royal’s extravagant stories; and then Lucy walked away.

Lucy walked through the garden, and then climbed over the stile at the foot of it; and when at the top of the stile, she saw Royal sitting at a little distance in a shady place near some rocks.

“Ah, Lucy,” said he, when he saw her, “I am very glad that you have come; I want you very much. Come, run.”

Lucy descended from the stile, and walked along towards Royal pretty fast, but she did not run.

Royal was tying a knot, about his rigging; and he wanted Lucy to put her finger on to hold the first tie, until he secured it by a second. So he sat still, holding the ends of the thread, and waiting for Lucy to come.

“Why don’t you run, Lucy? Here I am waiting all this time,—while you are coming along so slow.”

“No,” rejoined Lucy, “I am not coming along slow. I am walking as fast as I can.”

“Walking!” repeated Royal; “well, that is coming slow. There, put your finger on there while I tie again.”

Lucy put her finger upon the place, saying, at the same time, that she did not think that all walking was slow. “I can walk very fast indeed,” she added.

“But I don’t see why you could not have run a little,” said Royal.

“Because,” said Lucy, “it is not proper for sick persons to run. I have not got well enough yet to run.”

Royal laughed aloud and heartily at this,—while Lucy looked disturbed and troubled. They came very near getting into a serious disagreement on this subject. They were both partly in the wrong. Royal ought not to have required Lucy to run to him, in that absolute manner, as if he had any right to claim that she should do it. But, then, on the other hand, when Lucy saw that Royal was in haste to have her come quick, and do something for him, she ought to have had the kindness to have run. She was mistaken in supposing that her being sick was the reason; for, in about half an hour after this, when Royal went away to sail his vessel, she ran after a black butterfly, with yellow spots, for a considerable distance.

Any serious difficulty, however, between the children, was prevented by an occurrence which fortunately intervened. It happened that, soon after Lucy left the house, her mother asked Miss Anne to be kind enough to walk down through the garden, and see where she and Royal were sitting, in order to be sure that it was a safe place, as she wished to be careful that she should not incur any danger of taking cold.

Now, it happened that, just as the conversation between Royal and Lucy was beginning to take this unfavorable turn, Miss Anne appeared coming over the stile.

Lucy walked along towards Miss Anne, with a countenance expressing some uneasiness of mind, which Miss Anne immediately observed, and she said,—

“Well, Lucy, and what is the matter now?”

“Royal is laughing at me,” said Lucy, in a complaining tone. Here Royal laughed again. “And besides,” continued Lucy, “he wants me to keep running all the time.”

“O Lucy,” said Royal; “not so. I only wanted you to run once, a little; just to put your finger on the knot while I tied it. Do you think there was any harm in that, Miss Anne?”

“No,” replied Miss Anne, “not if you asked in a proper manner. If you demanded it of her, or spoke harshly to her because she would not come,—then you did wrong; for she was under no obligation at all to run.”

“He scolded me a little,” said Lucy, “because I would not run.”

“O no,” said Royal.

“A little,” replied Lucy. “I only said a little.”

“Did you know what he wanted of you?” asked Miss Anne.

“No,” replied Lucy. “Only I supposed he wanted me to do something about his ship.”

“Well, I think, as he was waiting for you, you might have run along a little, Lucy. We ought to be willing to help one another. It is as much a duty to be kind to each other in little things as in great things; so that I think you were both somewhat to blame.”

“What was I to blame for?” asked Royal.

“For finding fault with her for not running,” replied Miss Anne, “and for speaking to her as if you had a right to require it of her. She was certainly under no obligation to come and help you at all, unless she chose to, herself.”

“Why, Miss Anne!” said Royal; “is not every body under obligation to do their duty? You said just now that it was Lucy’s duty to come.”

Miss Anne did not immediately answer this question, but stood still, looking into vacancy, as if thinking; and presently a smile, of a peculiar expression, came over her face.

“What are you laughing at, Miss Anne?” said Lucy.

Miss Anne did not answer, but only smiled the more.

“Miss Anne,” said Lucy again, pulling her hand, “what are you laughing at?”

“Why, I am laughing,” continued Miss Anne, “to think how I am cornered.”

“What do you mean by cornered?” asked Lucy, looking perplexed.

“I don’t see,” continued Miss Anne, “but that I am checkmated entirely.”

“What does that mean, Miss Anne?” asked Lucy. “I don’t understand one word you say.”

“Why, I told Royal,” replied Miss Anne, “that it was your duty to have helped him, and——”

“But I did help him, Miss Anne,” said Lucy.

“But I mean, to run along quick to help him,” replied Miss Anne.

“I did walk along as quick as I could,” said Lucy, “and I am not well enough yet to run.”

“Because I said it was your duty to make an exertion to do him a kindness,” continued Miss Anne, without appearing to notice much what Lucy said. “And that seems to be true, without any doubt. But, then, on the other hand,” she continued, “I told him that he did wrong to require it of you, for you were under no obligation to do it. That, too, seems to be true, without any doubt. Both seem to be true, considered separately; and yet, when brought together, they seem to be inconsistent; for, as Royal says, we are all under obligation to do whatever is our duty. I don’t think that I can get out of the difficulty very well.”

“I don’t see that there is any difficulty at all,” said Lucy; “for I am sure that Royal ought not to make me run when I am sick.”

The truth was, that Lucy was not old enough to understand metaphysical reasoning very well,—or any reasoning, in fact. So they dropped the subject. Miss Anne would not go on talking, and pretending to understand the subject, when really she did not; and Royal, satisfied with his victory, was desirous of turning his attention to his vessel.

“Who is going to make your sails for you, Royal?” said Miss Anne.

“I shall have to make them myself, I suppose, unless you will. See, there is my sail-cloth.”

Miss Anne looked upon a little sort of shelf in the rock where Royal kept his stores, and saw there a piece of white cotton cloth, neatly folded up, and lying in one corner. By the side of it were a pair of scissors and a spool of thread.

“Where are your needles?” asked Miss Anne.

“They are in the spool,” said Royal.

“In the spool!” repeated Miss Anne. She had never heard of needles in a spool.

“Yes,” said Royal; and he took up the spool, and showed it to Miss Anne. There was a hole through the centre of it, as is usual with spools. One end of this hole Royal had stopped with a plug, of such a shape that, when it was in, the end of it was smooth with the end of the spool; so that the spool could stand up upon this end for a bottom. Then, at the other end of the hole Royal had fitted a stopper, with a part projecting, by which he could take it out and put it in.

Thus the spool made quite a good needle-case. Royal kept it thus always in readiness for making his sails, and for rigging his little ships.

“Very well,” said Miss Anne; “and now where’s your thimble?”

“I have not got any thimble,” said Royal. “I don’t know how to sew with a thimble.”

“Well,” said Miss Anne, “if you will cut out your sails, I will hem the edges for you. Lucy and I will walk along up towards the house, where I can get a thimble; and then I can be at work, while walking back slowly through the garden.”

Royal did this, and Miss Anne made his sails. They were better sails than he had ever had before. And so much interested did they all become in this work, that Lucy did not think of the stories which Royal had promised to tell her. So she did not hear the extravagant story until another time.