CHAPTER IV.

WHERE IS ROYAL?

LUCY came one evening and climbed up into her father’s lap.

“Father,” said she, “I wish you would let me study something besides what I study now.”

“Why, what do you study now?” asked her father.

“Only reading and spelling at school, and arithmetic at home with Royal.”

“Isn’t that enough?” said her father.

“No, sir,” replied Lucy; “I want to study something else.”

“Well,” said her father, “I’ll give you something to study, and I’ll study it with you.”

“O, well,” said Lucy, much pleased.

“Let me see,” added her father, looking around the room. “What shall it be? What shall we study? I’ll tell you; we’ll study the windows.”

“O father,” said Lucy, “we can’t study the windows.”

“O, yes,” replied her father, “there is a great deal to be learned about windows. Look at one of the windows, and tell me what you observe.”

So Lucy looked at the window a moment, and then said,—

“No, father, I don’t observe any thing about the windows at all.”

“I observe several things that are peculiar.”

“What do you mean by peculiar, father?” asked Lucy.

“Why, whatever one thing has, which other things do not have, is peculiar to it. Thus roots are peculiar to plants, for other things do not have roots. Now, look at the window, and see if you find any thing peculiar in it.”

“No, sir,” said Lucy; “I think it is just like all other windows.”

“But I didn’t wish you to find any thing peculiar to this window alone, which distinguishes it from other windows, but something peculiar to all windows, which distinguish them from the other parts of a building. I notice one thing which is very peculiar.”

“What is it?” said Lucy.

“Why, they are transparent.”

“What is transparent?” asked Lucy.

“Any thing that you can see through is transparent,” said her father. “Water is transparent; glass is transparent; some ice is transparent. Now, windows are made of glass, which is transparent, for two reasons: First, in order that the light may shine in and illuminate the room, so that we can see to walk about in it, and to read, and to sew. The other reason is, that we can look out through the window, and see the scenery, and the persons pass along the street. Those are the reasons why windows are made of something transparent.

“There is also something peculiar,” said her father, “in the mode in which windows open. How do they open?”

“Right upwards,” said Lucy, making a motion with her hands, as if she was opening a window.

“And how do doors open?” asked her father.

“Right sideways,” said she.

“Now, can you think of any reason why windows should open by sliding upward, and doors by swinging out upon hinges?

“First, why shouldn’t windows open like doors, by swinging out upon hinges?”

“Why, they might get broken by the wind,” said Lucy.

“Yes,” said her father; “doors are very often shut violently by the wind; and this would doubtless often happen to windows, if they were hung in a similar manner.”

“Once I saw a house,” said Lucy, “where the window was broken, and the people had put a piece of board in the place of the glass.”

“Yes,” said her father, “perhaps they had no more glass. But there is another reason why windows shouldn’t open like doors. Can you think what it is?”

“No,” said Lucy, “I can’t think.”

“If windows opened upon hinges, like doors, they must either open outward into the open air, or inward towards the room. If they were made to open outward, then, when they were wide open, they would swing back against the side of the house, and it would be very inconvenient to reach them to shut them.”

“We could go out of doors,” said Lucy.

“Yes,” replied her father, “but that would be very inconvenient, especially if there came up a sudden shower of rain, and we wished to shut the windows quick.

“But, on the other hand,” continued her father, “if the windows were made to open inwards, then they would be apt to knock the things over on the table. We often have a table before a window, but we never have a table before a door; for it would be in the way when we wanted to pass in and out. So you see the reasons, why it is better that windows should be made to slide up and down, and doors to open upon hinges.”

“But, father,” said Lucy, “why couldn’t doors be made to slide up and down like windows?”

“Think of it yourself,” said her father, “and see if you can think of any difficulty.”

“Why—yes,” said Lucy. “Suppose they wanted me to open the door. Well, and then they tell me to shut the door: well, then I go and try, but I can’t reach up to the door: well, then I get a chair, and I try to climb up, and—and the door sticks, and I can’t pull it down, and perhaps I tumble down and hurt me. An’t those difficulties?”

“Yes,” said her father, “and perhaps, too, the door would sometimes be left not shoved up quite high enough, and then people would bump their heads.”

“Yes,” said Lucy; “and, father, Georgie bumped his head the other day, and the teacher asked him to spell bumper.”

“And did that make him forget his pain?”

“Yes, sir, but he didn’t spell his word right.”

“Didn’t he?” said her father. “Then his experience of the thing did not teach him the orthography of the word.”

“What, sir?” said Lucy.

“His experience of the thing did not teach him the orthography of the word,” repeated her father.

“I don’t know what you mean by that,” said Lucy.

“Why, by bumping his own head, he experienced the thing, but yet he could not spell the word. The orthography of a word means the spelling of it.”

“I did not know that before,” said Lucy.

“Then I should like to have you take pains to remember it,” said her father.

“I don’t think I can remember such a long word,” said Lucy.

“The way to fix it in your mind,” said her father, “is to repeat it a great number of times. Say orthography.”

So Lucy repeated the word after her father.

“Now repeat it ten times,” said her father, “and count by means of your fingers.”

So Lucy repeated the word orthography ten times, touching the thumb and fingers of her left hand in succession as she did so, and then the thumb and fingers of her right hand. By doing this, she rendered the sound of the word somewhat familiar, and also accustomed herself to pronounce it.

“Now,” said her father, “go out and find Royal, and tell him all I have told you about windows; and also tell him that orthography means spelling. That will help you remember the whole lesson.”

“Is that a lesson?” said Lucy.

“Yes,” said her father, “it is a lesson; and it will be quite a good lesson for you, I hope. It will teach you to observe particularly what you see; and to-morrow morning I will give you the sequel to it.”

“What do you mean by sequel?” said Lucy.

“I will tell you when I am ready, to-morrow, to give you the sequel.”

So Lucy went away to find her brother Royal.

She thought it probable that he was in the back yard or garden, but she could not find him in either place. She stood at the garden gate, and called,—

“Royal! Royal! where are you?”

But there was no answer.

“Joanna,” said Lucy, “do you know where Royal is?”

For, just at that moment, she saw Joanna sitting at the window of her room.

“No,” said Joanna, “I don’t know; but he can’t be far off, for it is only a few minutes since I heard him whistle.”

“Whistle?” said Lucy.

“Yes,” replied Joanna; “it sounded as if he was blowing some whistle, which he had made out of a willow.”

“I wish I could find him,” said Lucy.

Just at this moment, Lucy heard a long-drawn and very clear whistle, which seemed to be very near.

“Royal!” said Lucy; “Royal! is that you? Where are you?”

There was no answer, but only a repetition of the same shrill and long-protracted sound.

Lucy began to look eagerly around the yard.

“Royal!” said she, “Royal! is that you whistling?”

Another long whistle.

“Ah, Royal,” said Lucy, “I know where you are; you’ve hid somewhere. I know you.”

So saying, Lucy began to look around the yard in every direction, but no Royal was to be seen. She went to the garden gate, and looked under the shrubbery, but there was no Royal there.

At length she paused, not knowing where to look next; and, after resting a moment, she said,—

“Whistle again, Royal.”

So Royal whistled again. The sound seemed to come from upwards, and Lucy looked up towards the house.

“Ah,” said she, “Royal, I know where you are. You are in the house, by some of the windows. I know—you are at mother’s window—or else at Joanna’s. Joanna, isn’t he in your room?”

“No,” said Joanna.

“And don’t you know where he is?”

“Yes,” said Joanna.

“Well, tell me then; do, Joanna. I’m tired of looking for him.”

Joanna only smiled; and Lucy, finding that she could get no information from her, said that she knew Royal was in the house; and she ran in, and went up stairs to search the chambers which looked out towards that side of the house, especially such as had any windows open. She looked in them all in vain. Then she went into Joanna’s room, and stood by her side, leaning her arms upon the window sill, and looking out the window.

“Royal,” said she, “I should think you might tell me where you are.”

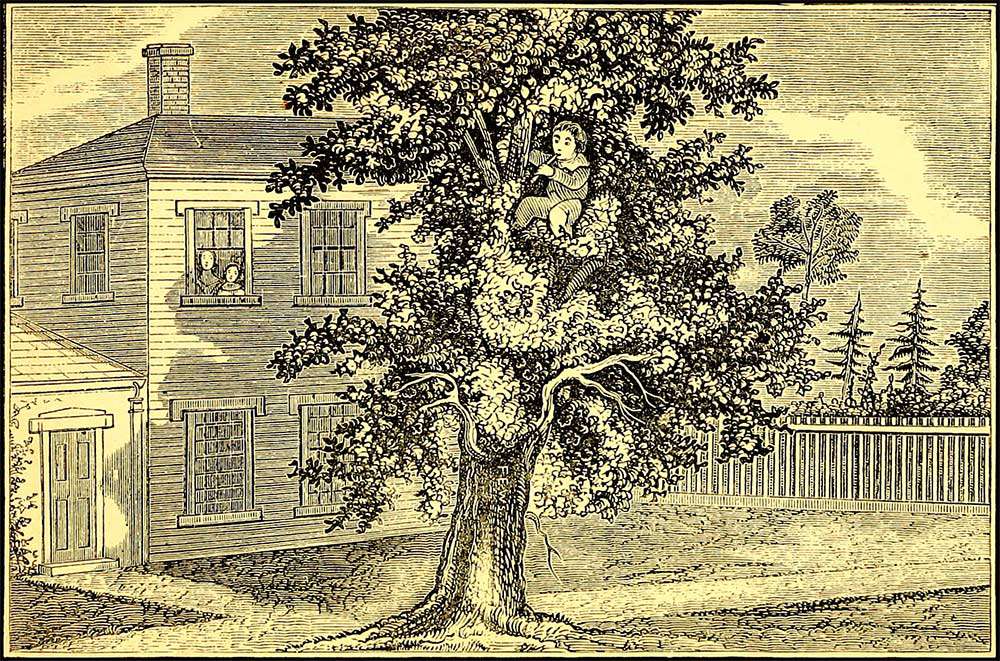

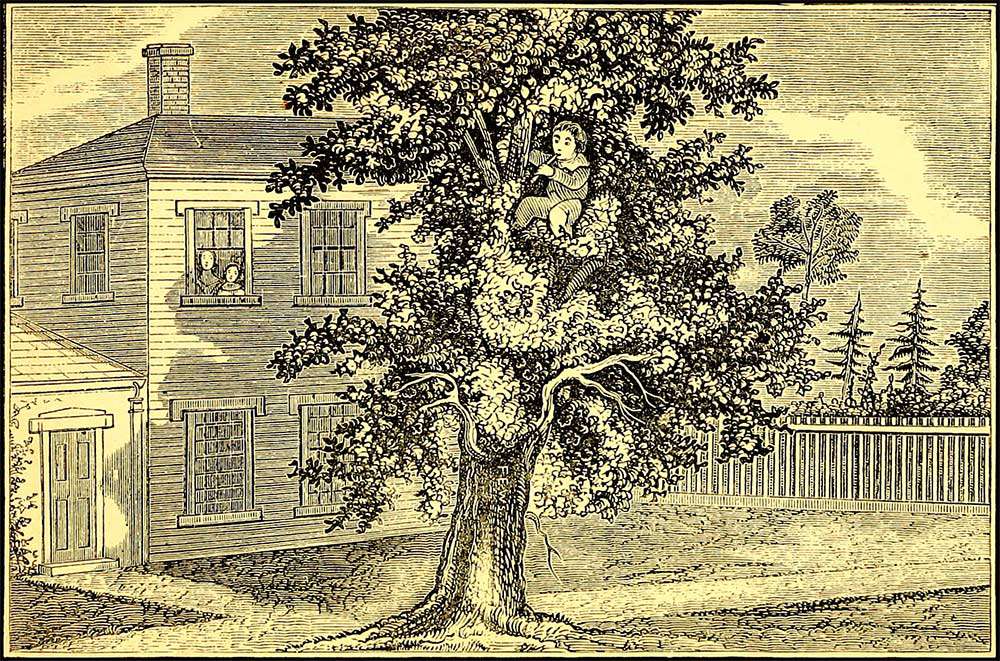

“‘Royal,’ said she, ‘I should think you might tell me where you are.’”—

Royal answered by calling out, C-o-o-p; just as the children were accustomed to do, when playing hide and go seek. The direction of the sound of a voice is generally more perceptible than that of a whistle; and it was particularly so in this case, for Lucy at once perceived that the sound came from somewhere in the air. She looked up in the direction from which the sound seemed to proceed, and, to her great astonishment, saw Royal comfortably seated near the top of a great oak-tree, which stood in the corner of the yard. He was almost concealed by the branches.

“Why, Royal!” exclaimed Lucy; “what are you doing there?”

“Making whistles,” said Royal.

“O Royal!” exclaimed Lucy again.

She found, on examining more particularly his position, that he had placed a short board across from one branch to another for a seat, and that at a short distance below he had placed another board, which answered to put his feet on. The board on which he sat extended out a little way beyond the branch where it rested, and this Royal used for a sort of shelf, to put his pieces of whistle wood upon, and his knife, when he was not using it. Two whistles, also, which he had finished, were lying here. Royal was making another; and he went on very gravely with his work, while Lucy was wondering at his position.

“Lucy,” said Royal, “do you want a whistle?”

“Yes,” said Lucy.

“Come out, then, into the yard, and I will throw you one down.”

Lucy accordingly ran out, and Royal, taking up one of the whistles, which he had made, tossed it out from among the branches of the tree. It sailed out horizontally through the air, and then, turning downward, it began to descend in that beautiful curve, which bodies projected from a great height always describe, and at last it came down to the ground.

But it was now some time after sunset, and it was not very light in the yard. Lucy went to the place where the whistle had fallen, and looked for it among the grass, but she could not find it. However, Royal himself came down pretty soon, and, after a little search, he found it close to Lucy’s foot. The interest which Lucy felt in this incident drove all thoughts of the lesson on windows from her mind; and so she did not get the sequel to the lesson, which her father had promised her.

What her father had intended by the sequel to the lesson was this: He was going to send Lucy into one room, and Royal into another, and let each of them examine a fireplace, so as to observe its peculiarities, and then to come in and tell him what they were; and also to ask him for the reason of any thing they noticed about the fireplace, which they did not understand.

They did not do this, however, until the next day; and then, when they came in from the examination of the fireplace, Lucy said that she observed one peculiarity about the fireplace, and that was, that the back of the chimney was black, and that she did not understand why the fire, which was red, should make the bricks black. Royal said that he observed, that there was always a mantel shelf over a fireplace, and he did not see why they always had a mantel shelf over a fireplace, rather than in any other part of the room.

“But, father,” said Lucy, “what is a sequel?”

“A sequel of any thing,” replied her father, “is that which comes in consequence of it, and is the conclusion of it.”

“I don’t understand that very well,” said Lucy.

“Never mind,” replied her father; “I can’t explain it to you any more now.”

So Lucy went away.