CHAPTER XXI.

AN INNOCENT SUFFERER.

THE house had never been a lively house, but it had turned into the dreariest of habitations now. All those comforts which Miss Hofland had felt to make up for so much did not compensate for the absence of Hetty, or what was worse, for the presence of Hetty, spell-bound in that great chair, and for the innocent questions of Rhoda, who asked and asked, every new demand being but an echo of the questions which already were thrilling through the governess’s heart. “But why?” Rhoda said. “What made her like that? What has happened to her? Things can’t happen, can they, without a cause? Why has Hetty turned like that? She was never like that before. If you will not tell me I will ask Mr. Darrell; he is the doctor, and he must know.”

“She got some dreadful fright, my dear. Don’t speak to Mr. Darrell, for I don’t think he knows; and if he does know, he would not tell a little girl like you.”

But this answer did not satisfy Rhoda. She caught Mr. Darrell, as it happened, exactly at this moment when he was going out. “Oh, Mr. Darrell, I want you to tell me what has made Hetty like that. What is the matter with Hetty? Oh, yes, I have seen her. Do you think they could shut her up and hide her from me? Mr. Darrell, what has happened to Hetty? You are the doctor, and you must know.”

“The doctor doesn’t know everything,” he said.

“But very near everything,” said Rhoda. “She is very ill, I am sure. Tell me what it is, and I won’t trouble you any more.”

“I can’t tell what it is,” said the young doctor. “I wish I could, then perhaps I might know how to make her better. I am going now to send for some one who perhaps can do it. It is only perhaps, but I am going to try.”

“Another doctor?” asked Miss Hofland. “I can understand that you don’t like the responsibility. I shouldn’t if I were in your place.”

“Not another doctor, at present, but her mother,” Mr. Darrell said; and he went off and left them, though it was scarcely civil to do so, when they had so many questions to ask.

“Her mother!” Rhoda said, pondering. “Is it a good thing to bring her mother? What good can her mother do her? She is not a doctor. I should think Mr. Darrell himself would be more good than that.”

“Oh, my dear, the very sight of your mother makes such a difference when there is anything the matter with you,” said Miss Hofland. “At least,” she added presently, “all the girls say so. I never had one, for my part.”

Rhoda looked up at her with intelligent but unfathomable eyes, and said nothing. It appeared that the words did not bring any warmer response from Rhoda’s heart.

But it would be vain to attempt to describe the agitation and trouble which was caused in the parsonage by Mr. Darrell’s telegram. “Will Mrs. Asquith come at once? Daughter ill, not dangerous, but critical. Carriage will meet nine-thirty train.”

“It must be something very bad,” Mary said.

“No, my dear, I hope not. ‘Not dangerous, but critical.’ You must not frighten yourself. You must husband your strength,” said the parson; but he spoke with a forced voice, and had grown very pale, paler indeed than she was; for she had so many things to think of, and he thought only of Hetty—poor little Hetty, papa’s pet, as they always called her—ill and far from home.

“You must take charge of the little ones, Janey. You must not let them make a noise or annoy papa; you must see that the boys have their breakfast in good time for school, and don’t let Mary Jane oversleep herself. Papa will let you have the little clock with the alarum in your room.”

“Oh yes, mamma! I will try and remember everything,” said Janey among her tears.

“Get in the books every week, and look over them carefully. Don’t let anything be put down that we haven’t had—you know how careless people are sometimes; and above all keep the house quiet when papa is in his study. You know the importance of that.”

“Oh, mamma!” said Janey, “do you think then that you shall be so very, very long away?”

“I hope I maybe back again to-morrow, or the day after to-morrow,” said Mary briskly. “It will depend upon how I find her. I don’t doubt in the least home will be the best thing for her; but in case I should be detained,” she said smiling, with her eyes very bright and liquid, each about to shed a tear, “it is so much better to mention everything. Of course I shall write; but, Janey dear, you know you have not the habit of minding everything as—as she had——”

“Oh, mamma, why don’t you say Hetty? Why don’t you call her by her name? It is so awful to hear you say she, as if—as if——”

“Didn’t I call her by her name?—my dear little Hetty, my own little girl! Oh! and to think that it was I that sent her away!”

“It isn’t dangerous, Mary, we have got the doctor’s word for that,” said her husband.

“Oh yes, to be sure we have. I am not at all frightened. You know when anything is the matter with her she gets very down, and strangers would not understand. I am all ready, Harry. No, I don’t want a cab. One of the boys can carry my bag to the station, and I would rather walk. I shall have no fatigue, you know, in the railway; it will be quite a rest for me, sitting still for so many hours.”

“A third-class journey is not much of a rest,” said the parson, shaking his head.

“And the carriage to meet me when I get there,” said Mary with a smile; “I shall feel quite a lady again, like old times, stepping out of the third class.”

Half the family went with her to the station to see her off. Janey had to deny herself and stay at home with the little ones, and keep everything in order; for Mary Jane was young, and not to be trusted all by herself. Janey felt as if her heart was wrenched out of her when mamma went away to nurse Hetty, who was ill and perhaps dying, while she must stay here and watch the little ones playing, who knew nothing about it and could not understand. To have gone with her to the train and seen her go away, as the others did, would have been something, but even that solace was denied. To the younger ones it was something like an unexpected gaiety to see mamma off, and watch the bustle of the train. They had little or no doubt that Hetty would be all right as soon as mamma went to take care of her, and the boys could not help feeling a little important as they relieved each other in carrying the bag.

Mary, for her part, when she had got into the train and smiled for the last time at the eager group, and waved her last good-bye, had a very sad half-hour in the corner, with her veil down, crying and praying for her child. But after that she tried not to think, which is one of the hardest of the habitual processes through which a mind has to go which requires to be always fit for the service of a number of others, and consequently has to keep itself well in hand. She had been obliged to do this many times before, and though it was harder than usual, now that she was alone and had no immediate occupation to take off her thoughts, yet she did more or less succeed in the effort. There was a poor weakly young mother in the carriage, going to join her sailor husband somewhere, with a troublesome baby whom she could not manage. And this was a great help to Mrs. Asquith in keeping off thought and subduing the pain of anxiety. She said to herself this was one advantage of the third class. Had she been travelling luxuriously with a first-class compartment all to herself, she would not have been able to stop herself from thinking. This softened even the thrill of old associations which went through her, when, looking up as the train stopped, she perceived the little station; and, beyond it, the familiar landscape which she had not seen for so long. Was it only sixteen years? It looked like centuries, and yet not much more than a day. Nothing, however, had ever been at Horton in her time like the spruce brougham which was waiting for her, with the smart footman—smarter than any one in the service of the Prescotts had ever been. Amid all the familiarity and the strangeness Mary’s heart sank within her when the servant came up. “The young lady’s just the same, madam,” the man said.

“Can you tell me what’s the matter? Oh! can you tell me?”

“I don’t know, as no one knows,” said the servant, as he arranged a rug over her knees.

“Oh, if you will be so kind—as fast as you can go,” said Mary.

He seemed to look at her pitifully, she thought. All better hopes, if she had any, flew at the sight. She felt now that Hetty must be dying, that the case must be desperate. This delivered her from all feeling in respect to the old house where she had been brought up, the fields, the trees, the park—everything which she had known. What did she care about these associations now? She was as indifferent as if she had been but a week away, or as if she had never seen the place before.

The doctor met her at the door, looking so grave. She prepared herself for the worst again, and entered the old home without seeing or caring what manner of place it was. “Let me explain to you before you see her, Mrs. Asquith,” Darrell said, leading the way into the old library, which she knew so much better than he did.

“Oh, don’t keep me from her! Let me go to my child! Don’t break it to me! I can see—I can see in your face!”

“She is not in any danger,” he said.

Mrs. Asquith turned upon him with a gasp, having lost all power of speech: and then the self-control of misery gave way. She dropped into the nearest chair, and saved her brain and relieved her heart by tears. “May I trust you?” she asked piteously, with her quivering lips; “Hetty, my child—is in no danger?” as soon as she was able to speak.

“None that I can discover; but she is in a very alarming state. She has had a fright. It seems to have paralysed her whole being. I hope everything from your sudden appearance.”

“Paralysed!”

“I don’t mean in the ordinary sense of the word—turned her to stone, I should say. Oh, Mrs. Asquith, I fear you will think we have ill discharged the trust you gave us. Your daughter has been frightened out of her senses, out of herself.”

Mary had risen from her seat to go to her Hetty; she stared at him for a moment, and dropped feebly back again. “Do you mean that my child—my child is—mad?” she said with horror, clasping her hands.

“Oh, no, no!” cried the young doctor. “Her mind, I hope, may not be touched. She is in a state I can’t explain. She takes no notice of anything. I thought it was catalepsy at first. You will be more frightened when you see her than perhaps there is any need for being——”

“Doctor—if you are the doctor—take me to her, take me to her! that is better than explanation.”

“Bear with me a little, Mrs. Asquith. I want you to come in suddenly. I want to try the shock of your appearance.”

“Take me to my child!” said Mary; “I cannot bear all these preliminaries. I have a right to be with Hetty, wherever she is. Where is she? Tell me what room she is in. I know my way.”

“Just one moment—one moment!” he said. He led the way to the room which had been the morning-room in Mary’s day, the brightest room in the house, looking out upon the flowers, and then left her at the door. “Come in,” he said, “in five minutes; throw open the door; make what noise you can—oh! forgive me—and let her see you fully. Don’t come too quick. It is for her sake. If she knows you, all will go well.”

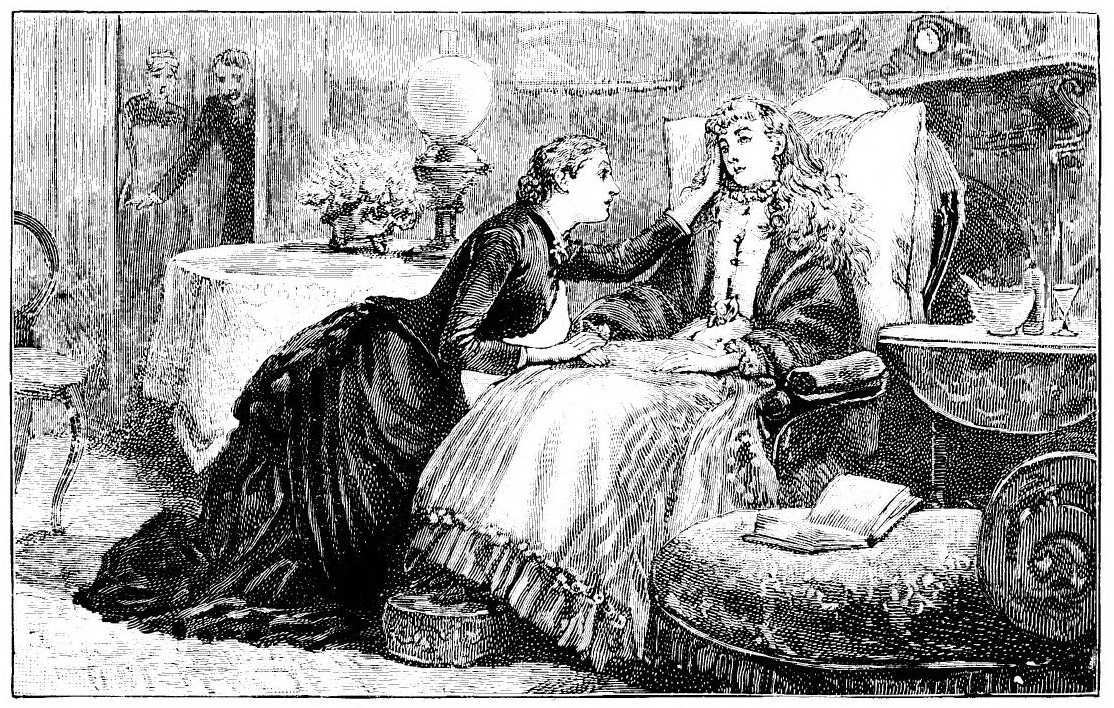

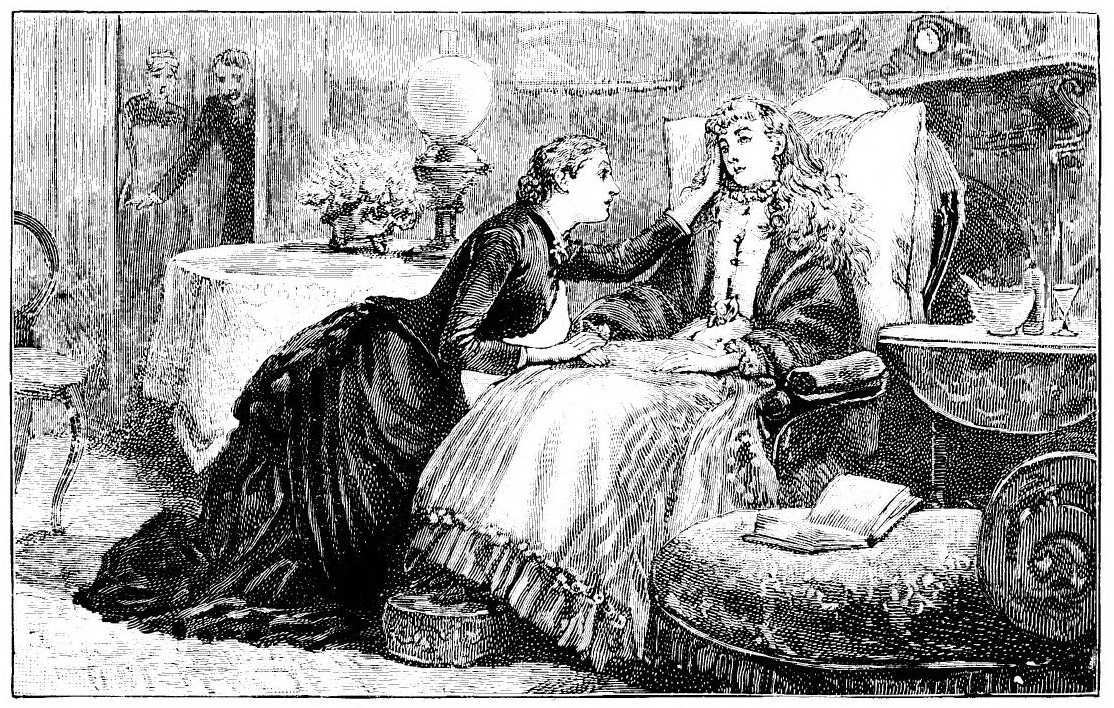

“If she knows me!” cried poor Mary. These terrible words subdued her in her impatience and almost anger. She stood at the door counting the time by the beatings of her heart. Then she pushed it open, as he told her. Hetty’s chair had been turned round to face the door, and she sat in it, her pale hands folded in her lap, her face, like marble, against the white pillow, her eyes looking steadily before her, with an extraordinary abstract gaze. Mary stood for a moment, herself paralysed by that strange sight, clasping her hands, with a cry of trouble and consternation. Then she flew forward and flung herself on her knees before this marble image of her child. “Hetty! Hetty! Speak to me,” she cried, clasping her arms round the inanimate figure. “Hetty!” Then, with a terrible cry, “Don’t you know your mother? don’t you know your mother, my darling, my poor child?”

Mary perceived none of the people behind,

“‘HETTY! HETTY! SPEAK TO ME.’”

watching so anxiously the effect of her entrance, which had been indeed far more effective, being entirely natural, than anything they had planned. She saw only the waxen whiteness, the unresponsive silence, of the poor little soul in prison. She went on kissing the white face, the little limp hands, pouring out appeals and cries. “Oh, my child! Oh, Hetty, Hetty! Don’t you know me? I’m your mother, my darling. I’ve come to fetch you, to take you home. Hetty, my sweet, papa’s breaking his heart for you; and poor Janey daren’t even cry, dear, for she must take care of them all while you and I are away. And, Hetty, the baby, your little baby—Hetty, Hetty! my own darling! Oh, Hetty, say a word to me—say a word!”

The statue moved a little; a faint tinge of colour came into the marble face; the limp little hands unfolded, fluttered a little, made as though they would go round the mother’s neck. “Mamma!” Hetty said, stammering as when a child begins to speak.

And then there awoke a chorus of voices saying, “Thank God!” The women were all over-joyed, thinking the worst was past. Darrell had said if she recognised her mother—and it was evident that she had done so. But he himself stood aloof, keeping his troubled looks out of their sight. And after Mrs. Asquith had sat by her daughter’s side for hours, telling her everything as if Hetty fully understood, saying a hundred things to her—news of home, caresses, tendernesses without end—it presently became evident to all that very little real advance had been made. Hetty said, “Mamma!” as she had said, “Thank you,” but she did no more.