DICEY LANGSTON

1787

There was a pleasant mellow glow in the great low-ceiled kitchen, and the absolute quiet was unbroken save for an occasional crackling of the sticks which made a bright fire on the hearth. Yet, if the room was still, it was but because Dicey chose it so, and as she stood beside the huge wheel which a few moments before had been whirling merrily, she looked with thoughtful eyes at the fire.

Now, to tell the truth, Dicey did not like to be alone, nor was it usual for her to be silent. The every-day Dicey was singing if she was not talking, or spinning if she was not busy about the house, or flying here and there on errands for her father, or hunting up the brothers to do this or that,—to play or ride, or come to meals or something,—for Dicey was quite a little queen, as a girl with five big brothers has a right to be.

A father and five big brothers, but no mother, poor little girl! and she had grown to be sixteen years old, the pet of her brothers and the darling of her father’s heart, and, as you may guess, somewhat spoiled and self-willed. Yet I would not have you think for a moment that she was selfish, for she was not so; but she had grown to depend very much on herself, and to decide for herself many questions which other girls who had mothers to turn to would have left to them.

Dicey’s father was no longer a young man. Indeed, he was almost past middle life when, ten years before, he had left his home near Charleston, shattered in spirit by the death of his wife, and gone to the “Up Country,” as the northern part of the State of South Carolina was called, and started life anew. Dicey hardly remembered the old home at all. Her thoughts and her affections were all centred about the comfortable home in whose kitchen she now stood, and over whose comfort she reigned.

She stood for many minutes as we saw her first, quite motionless, and then, as the evening air brought to her ear a sound so slight that you or I might not have noticed it, she ran to the window and looked out.

The house stood in the centre of a clearing on the top of a gentle ridge, and flowing out on either hand were dales and hills still covered with the forests through which the hunters and cow-drivers had wandered years before. Through this country the Catawbas and the Cherokees roamed, and but a short distance from the little settlement of which Solomon Langston’s house was a part, lay that well-known Indian trail called the “Cherokee Path,” which led from the Cherokee country on the west to the lands of the Catawbas on the east.

On the flat lands below the hills stretched wide plains destitute of trees and rich in fine grass and gay with flowers. Here roamed the buffalo, elk, and deer. Here also were wild horses in many a herd, and it was from one of these wandering bands of horses that Dicey’s own little pony had been captured by brother Tom, before he married and went to live at “Elder Settlement” across the Tyger River, a deep and boisterous stream, between which and the Enoree lay the plantation where Dicey’s father had made his home.

All this time she has been standing at the window, looking out over a landscape which lay clear and white before her in the moonlight. The slight sound which had caught her ear was getting louder every moment, and at last two figures came into view, her father and one of her brothers, who had ridden early that morning to the settlement “Ninety-six” to hear the latest tidings about the War, and to gain some news regarding the revolutionary movement which hitherto had been largely confined to the southern portion of the State.

For Dicey it had been a long and weary day. Her father’s last words were: “Let no one know where we have ridden, Dicey, for in such days as these it is best to keep one’s own counsel, and you know, little daughter, that most of our neighbours belong to the King’s party.”

And Dicey had remembered, even though Eliza Gordon had come over that afternoon with her sewing, and the two girls had worked on their new kerchiefs, fagoting and stitching and edging them with some Mignonette lace which Eliza’s mother had brought from Charleston when last she went to town. Such silence was hard enough for Dicey, who was used to tell whatever thoughts came into her mind, particularly to Eliza, who was her very “dearest friend.”

When Mr. Langston had dismounted, and Dicey had taken one look into his face, she cried out,—

“Oh, father, is the news bad? I can see by your face it is none of the best. Is that cruel King over seas never going to stop his taxing? Shall I throw out the tea?”

“S’hush, Dicey, my girl. Remember what I told you this morning. There are none others about us who think as we do, and it behoves us to be careful both in what we say and do.”

As he spoke, he drew Dicey into the house, and Henry followed, the horses having been taken to the stables by one of the slaves, who, like Dicey, had heard the sound of the riders and come forward to meet them. Once within doors Dicey forgot for a moment her eagerness for news, and ran forward to stir up the fire which had fallen low while she mused, and to light the candle which hung from its iron bracket on the back of her father’s chair. She set the kettle on the arm of the crane to boil, and put close at her father’s elbow his long clay pipe and box of tobacco, then brought out a tray with glasses and a generous bowl, into which she put spices and lemon, together with sugar and a measure of wine which she poured from a jug which was fashioned in the form of a fat old man with a very red face and a blue coat.

Kneeling on the hearth, she watched to see the steam come from the kettle’s nose, and as it seemed o’er long to her impatient spirit, she cast another billet of wood upon the dancing flames.

“Come, come, little daughter,” her father said, “Henry and I have ridden far, and your impatience does but delay matters. In truth, I am so weary and chilled that I am thirsting for the spiced wine, which your treatment of the fire does but delay.”

Now Dicey seized the poker and hastily endeavoured to make up for her error in putting on the new log, the only effect of her efforts being to make Henry laugh and take the poker from her hand, while he said,—

“Keep the little patriot quiet, father, since, if a watched pot never boils, this one is like to stay ever simmering.”

Mr. Langston held Dicey’s hand, and all fixed their eyes on the kettle, and as the first slender trickle of steam came from its nose, Dicey caught it from the iron arm, and soon had two fragrant glasses of hot wine ready for the travellers.

“Now, father,” she said, as she seated herself at his knee,—“now, father, the news!”

“’Tis true, Dicey, that at Gowan’s Fort many of our people have been horribly murdered.”

“Oh, father, not by Indians,” cried the girl, who well knew what this would mean.

“By worse than Indians,” answered Mr. Langston,—“by white men painted as Indians, who were even more cruel than the savages, if that can be.”

Dicey sprang to her feet and turned to her brother.

“Do you know if ‘Bloody Bates’ had anything to do with this, Henry?”

“Yes, he was the leader, and it is said that he boasted that his next raid should be in the country of the Enoree, where he said ‘dwelt so many fat Whigs.’”

“Just let him come this way,” cried Dicey, “and he will find that the fat Whigs are ready for him.”

Even though the case was grave enough, Henry and his father could not forbear a smile at the thought of Dicey, little Dicey, setting up as a match for the cruel bully who had made himself such a terror to the country-side by his midnight maraudings and treacherous killings that he had come to bear the name of “Bloody Bates.”

But Dicey, even though she was a girl, had a secret, and, what was stranger yet, she kept it, but in her brave little heart she resolved that if it were possible she would make it serve her friends.

So the next day she went forth in the afternoon carrying her work with her. Henry, who saw her start, little dreaming of the plans in that curly head, called out in a loud, cheerful voice,—

“I wager I know what is in that bag, Dicey. A new frock for dolly, made in the latest mode. But, Dicey, see that it be not of red, since our enemies are far too partial to that colour to suit me.”

“No such foolishness as you think, brother! I am to finish my kerchief which Eliza and I have been sewing on these three or four days. Maybe it will be all done when I come home.”

Dicey hurried on, almost afraid that she would let out the secret if Henry talked much longer about dolls. Dolls, indeed! why, she hadn’t looked at one for years!

Eliza saw her coming and ran to meet her.

“Come within doors,” said Eliza, when their greetings were over, drawing Dicey with her. But this did not suit our little patriot’s plans at all, and holding back, she said,—

“Let’s go and sit in the tree-seat, Eliza. ’Tis so pleasant out of doors to-day, and then you know we can talk over things there.”

“Go you there and I will come when I get my reticule,” answered Eliza, who, like Dicey, was glad to escape from the keen eyes of mother and elder sister, neither of whom had much sympathy for over-long stitches or puckered work.

Dicey did as she was bid, and climbed into the tree-seat where for years the children had been used to play, and, now that they had grown older, to which retreat they took their sewing or a book, though these latter came to hand rarely enough, the Bible and some books of devotion being thought quite enough reading for young people in those days.

When both girls were comfortably seated and thimbles and needles were ready, Dicey fetched a great sigh.

“What is the matter with you, Dicey? Have you aught ailing you?”

“No,” said Dicey, “nothing very much. I was wondering if, when this horrible war was ended, you and I should ever go to some great city like Charleston or Fredericksburg, as did your sister Miriam. Think of it, Eliza, to go to some great town where there are many houses and carriages, and a play-house, and, best of all, balls!”

At this magic word Dicey tossed into the air the little kerchief, and, ere it fell, was on the ground holding the skirts of her calico frock, bowing and smiling to an imaginary partner, now toeing this way and that, as if she were going through the dance, though, to tell the truth, the little minx had never seen anything of the kind, but had got her information from Eliza’s sister Miriam. All of Miriam’s knowledge had been acquired in safer and happier days, when she had made a visit to Fredericksburg, and astonished the young girls on her return with marvellous tales of what she had seen and heard, and the gaieties she had taken part in. Dicey and Eliza had often practised in secret, and though their steps would not have passed muster in a drawing-room, they had furnished them with pleasure for many an hour.

“Oh, Dicey, come up again! If mother sees you, she would make us come right away into the house; you know that she thinks that such things as dancing but waste the time of young maids like you and me.”

Thus urged, Dicey with a sigh took up the sewing again, and sat once more beside Eliza in the tree. But her thoughts were flying all about, and Eliza spoke twice ere Dicey noticed what she said.

“When father comes home to-night, he brings with him Colonel Williams.”

The remark seemed simple enough, but a sudden light flooded Dicey’s mind.

“Coming home,” echoed she; “why, you told me a day or two since that he would not be home till after harvest.”

“Yes, but things have come about differently,” answered Eliza, with an important air. “My father has been in a great battle, and he is coming with Colonel Williams to stay for a day or two till Captain Bates gets here too.”

“Captain Bates! Do you mean ‘Bloody Bates’?” asked Dicey, pale with horror.

“My father says that is but a Whig name for him, and that he has done good service to the King in subduing pestilent Whigs,” answered Eliza, bridling, and secretly pleased at the easy way the long words tripped from her tongue.

“That awful, cruel man coming here!” and Dicey half looked round to see if the mere speaking of his name had not brought upon the scene one of the most cruel bandits who under the name of scout had wrought endless cruelties. In a moment the importance of the information had shot into her mind! If she could find out something more! Sure, whatever Eliza knew were easy enough to learn also.

“Comes he here to rest too, and at your house, Eliza?”

If Eliza had given a thought to the low voice and shaking hands of her friend, she might have paused ere she told news which was of the greatest importance to such Whig families as lived in the neighbourhood, and more particularly to those who dwelt in the “Elder Settlement” on the other side of the river, and were entirely unprotected. Among them was Dicey’s eldest brother with his young wife and little family.

“Comes he here to rest too?” and Eliza, proud of her information, and entirely forgetting that she had been told to impart it to no one, answered briskly,—

“No, but he stops here to meet some of the soldiers who go with him, and only think, ’tis at our house that they will paint themselves just like the Cherokees!” At the mere thought Eliza clapped her hands. “Think how comical they will look,” she went on, while every moment Dicey felt herself getting colder and colder with fear. “And sister Miriam has done naught but scurry about and turn things topsy-turvy. It’s Captain Bates this and Captain Bates that, till one feels ruffed all the wrong way. You know I told you that he was coming here one day, and you laughed and said he dare not!”

Yes, Dicey remembered. This was the secret she had withheld, thinking that, like enough, it was but some of Miriam’s boasting that this savage man should seek her at her home. It was true, however, and like to be soon. How was she, Dicey, to warn those who were so unprotected?

Thinking more deeply than ever she had thought before, Eliza babbled on, her silent companion taking no note of what she said.

“Well, Dicey, if you cannot listen to what I say, and not even answer me, I shall go into the house. Besides, my kerchief is all done, and mother told me to bring it to her when the stitches were all set. How does it become me?”

As she spoke, Eliza threw it about her round white throat, and tossed her head, the exact copy of sister Miriam.

But Dicey was too absorbed to notice her companion’s small frivolities. Her thoughts were solely on how to get word to her brother of the impending arrival of “Bloody Bates” in the neighbourhood. Fears for the safety of her own home were not wanting, since Henry, the only brother left at the old homestead, was but waiting the summons to go and join the command of Colonel Hugh Middleton.

As Dicey walked slowly home along the bridle path which served for a road in that sparsely settled region, her mind had not thought of any plan by which her message was to be sent to her brother and his friends. Yet over and over the words formed themselves in her brain, “They must be told, they must be told.”

Her father was feeble, and these years of anxiety and of hard work since his sons had been called away from home to bear their share of hardships in the War to which there seemed no end, had enfeebled him still more. From him the news must be kept at any risk. Perhaps brother Henry would go; but while this thought passed through her mind, she saw him coming through the wood on his horse.

“I have ridden this way to tell you good-bye, little sister. Even now word was brought that I must join my company. Come hither”; and as Dicey ran to his side he bent down, saying, “Set thy foot on my stirrup, I have that to say which must not be spoken aloud.”

As Dicey did as he bade her, and stood poised on his stirrup leather, holding tightly to his hand, he whispered in her ear,—

“Be brave, little sister, and take the best care you can of father. He is ill and weak, and it vexes me sorely to leave such a child as you with no one stronger to protect you. Yet go I must, and I trust that before long Thomas may come for you and my father, or that Batty will return.”

As Dicey looked into her brother’s troubled face, the thought that he must not be told rushed upon her. Go he must, and they must take such care of themselves as they could. So she leaned forward, and said as cheerfully as possible,—

“Never fear for us, brother. There is no danger for father and me, for sure none would attack an old man and a young maid. See, I am not in the least afraid.”

“I could leave you with a better heart if I thought that were the truth, yet even as we have spoken thy cheeks have grown as white as milk, and see, your hand trembles like a leaf in the wind!”

Dicey pulled away that telltale member and jumped down from the horse.

“When the time comes, I’ll prove as good a soldier as any of the Langston boys, rest you assured of that,” she cried.

“Farewell, then, brother Dicey”; and Henry tried to cheer her by making her smile. Then, with his own face set in a look far too grave for one so young, he rode down the path in the flickering light, little dreaming of the desperate resolution which was forming in the mind of his sister. As she got the supper ready, and talked brightly as was her wont with her father, she had decided that she must be the one to take the news across to brother Tom at the Elder Settlement; and oh dear, oh dear, she must go that very night, for who could tell, perhaps “Bloody Bates” would stop there on his way, for she knew not which direction he was coming from. Yet for her father’s sake she was as much like her own cheerful self as she could be, and she forced herself to eat, as the way would be long and difficult. Twice she almost gave way to tears in the safe shelter of the pantry; yet do not blame my little Dicey, for though she felt fear, she never once thought of giving up her mission.

When her duties for the night were all done, and the hot coals in the fireplace carefully covered so that a few chips of light wood would set them blazing in the morning, Dicey sat down and tried to think out how she should manage. Her father was sleeping in his great chair by the fireplace, and he looked so worn and old that she resolved to take on her own slender shoulders the whole responsibility.

Perhaps it was her steadfast gaze, or perhaps it was his thoughts, which wakened Mr. Langston with a start, caused him to look quickly round and ask,—

“Where is Henry?”

“Why, father dear, Henry rode forth this afternoon to join Colonel Middleton. You have been napping, I think.”

“True, Dicey, I did but dream. ’Tis late enough for an old man like me, so light the candle, and I’ll to bed.”

As she handed the rude candlestick to him, Dicey threw her arms about his neck and swallowed hard to keep the tears that were so close to the surface from welling over.

“Why, child, what ails thee? One would think that I was to start on a journey too, whereas all I can do is to bide at home”; and Mr. Langston heaved a deep sigh as he said it.

“Brother Henry bid me take care of you, and I mean to, dearest father. Since you have sent five sons to this cruel war, it seems as if it might be that you and I were left at peace.”

“Yes, yes, daughter. I do but pray that I may live to see all my brave boys come home to me once more.” With bowed head Mr. Langston took his way to the small chamber opening off the living-room.

“Now,” thought Dicey, “must I plan and act. First must I write a few lines to father, lest he think that I too have followed brother Henry.”

She hunted about for a fragment of paper,—a thing not too common in a frontier farmhouse,—then she dashed some water into the dried-up ink-horn, and mended a pen as well as she could.

Will you think any the less of her if I tell you that poor Dicey was a wretched penman? Her days at school had been very few, since the nearest one was at Ninety-six, and her father could ill spare his little housekeeper. Yet he had taught her a bit, and as she sat and wrote by the flaring rushlight, I am afraid that her tongue was put through as much action as her pen. Poor Dicey! the little billet which caused her so much labour was intended to allay her father’s anxiety as well as to let him know where she had gone. Of the object of her mission there was never a word. That she would tell him on her return. The little scrawl was set on the table with one end beneath the candlestick, where he would be sure to see it in the morning.

“Dear Father,” it began. “I go to carry a message to brother Tom. I leave early in the morning, and will return as soon as might be. There is naught to fear for me. Your loving Dicey.”

“’Tis better,” she mused, half aloud, “to say ‘morning’ than to have him think that I was forced to go at night, lest I fall into the hands of some of these bandits on their way here. But I must not think of that, for I must be off as soon as I can get ready, and the faster I work the less afraid I am.”

She hurriedly put some food in a packet, and then crept up the stairs to her own tiny room under the eaves. You would hardly have known her when she came softly down a few moments later. Her hair was bound and knotted close to her head, for well she knew how the bushes and trees would catch the flowing curls. Her stuff gown was kilted high and held securely in place, while on her feet she had drawn a pair of boots which were her brother Batty’s, and, though large, they were stout and strong and came nigh to her knees. A heavy shawl covered her shoulders and was tied behind, and into the front of it she thrust the packet of food.

As she went softly out of the door, she gave a last look toward her father’s room and then hastened on, anxious to give her warning and then hurry home. Dicey knew the way well, having been to visit her brother a number of times. But in her haste and excitement she had not thought that a path by day with company is a very different thing from the same path by night and alone.

Yet this did not daunt her, even though there were strange noises in the forest and elfin fingers seemed to reach out from the bushes and pluck at her as she tried to hurry on. Each twig which snapped as she trod on it brought her heart uncomfortably to her mouth, in a way she did not like at all. The woods were bad enough, but infinitely worse were the marshes where there was not even a foot-log, much less a bridge to take her over the worst places, and but for Batty’s boots she would have suffered cruelly from roots and stones.

Still she pressed bravely on. She gripped her hands and kept repeating, “Every step takes me nearer, every step takes me nearer,” till it made itself into a kind of tune. She dared not think that the worst was yet to come, and that the Tyger River with its brawling current had still to be crossed. When at last she heard a faint murmuring, it seemed to give her new strength, and she turned in that direction.

Just as the first gleams of dawn lighted the sky, she stood on the muddy banks of the river. She looked about her in the dim light and thought that she recognised the place as the ford where they usually crossed. So, quite exhausted, she threw herself upon the ground, saying to herself, “I will rest a few moments and take a bite of pone, for well I know that the water of the Tyger is deadly cold and muddy too.”

As she thought, she acted, and in a brief time rose to her feet, not with that springy lightness which was customary with her, but slowly and with effort. The long hard walk, the chafing of the boots which were too large for her, all made her feel stiff and lame, and as she waded into the water, it took all her courage to keep from screaming out.

In she went, a step at a time, thrusting one foot before the other to feel her way in the rushing water, and bewildered by the grey light and the heavy fog which lay above the water and hid the other shore. It seemed to her that the water was getting very deep, surely much deeper than when she went through it before, though on that occasion she was mounted safely on the back of her little pony.

“Oh, dear Molly, if only you were here with me now instead of safe at home in your stall”; and one or two tears rolled over Dicey’s cheeks to be immediately swallowed up in the swirling waters which every moment grew deeper around her.

She went forward, step by step, never once thinking of turning back; and now the wavelets reached her waist, and now they were breast high and so heavy that they threatened to draw her from her feet. Completely bewildered, not quite sure of her course since the opposite bank could not be seen through the low-lying fog, Dicey lost her track and wandered up stream instead of across. She noticed that the water, now just below her armpits, kept at the same height, and fearing that every moment it would grow deep enough to engulf her, she stopped a moment in her difficult course and looked about her.

What was that which she could dimly discern apparently advancing towards her? To her mind, already overwrought, it seemed “Bloody Bates” himself, as indeed it might have been, and with a shriek which she vainly tried to smother, she turned abruptly to the left and plunged with all the speed she could muster through the water.

Oh, joyful thought! The black stream was getting lower, it was but breast high now, and as she leaped and plunged along, with every movement it receded, till at last she stumbled on the bank, and lay there sobbing with fright and exhaustion. She heard a soft swish in the river, and hastily raised her head to find that what had so terrified her was a huge buck, which was now half swimming and half wading to shore himself.

Cold and wet, half dead with fright and fatigue, Dicey, at sight of her supposed enemy, laid her head on her arms and had a good cry.

“Only a deer,” she sobbed, and then began to laugh, and with the laugh, feeling better, she scrambled to her feet, saying to herself, “’Tis but two miles to brother Tom’s and then I am safe.”

The way was easier now, for it was a travelled path, made by Indians, it is true, and their cruel allies the British, but still it was daylight, and away from the river the air was clear and fresh,—too fresh for comfort to the shivering girl, who ran and stumbled in her haste to get her message delivered. The two miles dragged themselves away at last, and through the trees Dicey saw the group of rude houses which made the Elder Settlement, and ah! there was brother Tom already out of doors about his work.

As soon as Dicey saw him, she shouted, and when he looked up, he seized his gun, for a weapon lay ever within reach in those days. Little wonder was it that he did not recognise the small figure which ran towards him waving its arms and shouting words which he did but half catch. At the sound of the commotion Elie, his wife, came to the door, and at the first glance cried out,—

“Why, Tom, ’tis Dicey!” and ran out to meet her, fearful of bad tidings, since it was easy to see that the girl was almost at the limit of her strength. As soon as Tom realised who it was, he ran forward and caught her in his arms, and hurried into the house, his lips forming themselves into the one word, “Father?”

Dicey shook her head, and when Tom set her down on the stone hearth, she slipped down into a little wet heap with a pale face and eager eyes.

“Oh, brother Tom,” she began, as soon as she caught her breath.

“Stay,” said her brother, “is aught wrong with my father or brothers?”

“No,” said Dicey, “I came—”

“Then thy news will wait till thou art dry and warm, else we are like to have a dead Dicey instead of a living one. Elie, take and give her dry clothes, and I will make for her a mug of hot cider which will warm her through and through. From her clothes, the Tyger seems at flood these days.”

When Dicey, warm and dry once more, poured out her tale of warning, Tom hurried away to call the men of the settlement together. As the small handful of grave settlers came and heard the news, Dicey felt in their few words of thanks ample payment for what she had undertaken in their behalf. Nor did they hesitate in their course. Packing together what possessions were most valued, and driving before them the few cattle which remained, they and their families that very afternoon crossed the Tyger at the ford which poor Dicey had missed, and sought the protection of the fort at Ninety-six. The next day Dicey was left at her own home and in the arms of her anxious father.

She told her tale to him, sitting by his side and holding his hand, for he could hardly realise that his little girl, his Dicey, had been through an experience at which even a man might have hesitated.

“My child,” said he, “it seems but yesterday that I held you in my arms, and here you are a woman grown ere I thought it.”

Fondly stroking her soft hair, he looked into the fire and spoke half to himself,—

“’Tis like her mother; but a child to look on, yet with a heart of steel.”

“Why, father, you think too much of it; ’twas not so much after all. At least it seems so now that once more I am safe at home with you, though truly in the doing I was much afeared.” Looking round as she spoke, she caught sight of the noon-mark on the window, and, jumping up, exclaimed,—

“Why, father, here have we sat gossiping till it is nearly midday and not a thing made ready for dinner! Shame on me for a bad housekeeper!” and with that she bustled away to prepare the simple meal which was the daily fare of many a family living far from the towns. A pudding made of the white corn meal did not take long to stir together, and in a pot was soon stewing some bits of venison from the last deer which Henry had shot, part of which had been salted down for their winter supply. A portion of the pudding with a pinch of salt added, and baked on a hot iron shovel with a long handle, served instead of bread, and what was left would answer for their supper, with some of the cheese in the making of which Dicey was well skilled. There was always plenty of milk from their small herd of cattle.

After all had been settled for the afternoon, the trenchers washed and the pewter cups polished and set on their shelves, Dicey drew out her wheel and set herself at her spinning. The low whir and the comfortable ditty which Dicey hummed hardly above her breath set her father to dozing in his chair, and neither of the occupants of the kitchen was prepared for the crashing knock which came on the heavy door.

Before Dicey could reach it to set it open, a harsh voice cried out,—

“If you open not that door and quickly, we’ll smoke out all of you!”

Dicey drew back, looking at her father for counsel.

“Draw the bolt, child,” he said; “we have no strength to withstand them. Our very weakness must be our protection.”

Dicey pulled back the great oaken bar which served as a lock, and in pushed half a dozen men heavily armed, none of whom she had ever seen before.

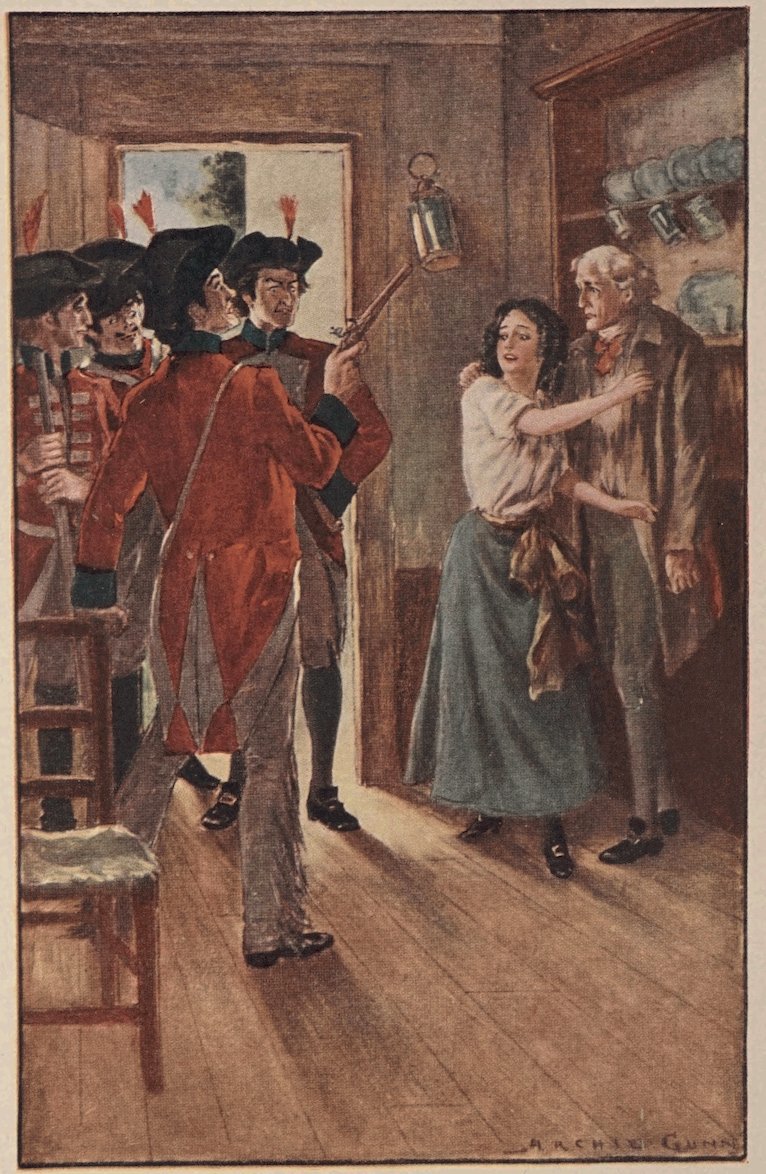

“COWARD, SHOOT NOW IF YOU DARE!”

“So the Whig cub has gone, has he?” asked the one who seemed the leader, a tall man dressed in buckskin trousers of Indian make, over which the red coat of the British officer seemed odd enough.

“It is true that my son has gone forth to serve his country,” said Mr. Langston, in a quiet voice.

At the reply, which seemed to enrage the ruffian, he strode a step forward, cocking his pistol as he advanced.

“I’ll show him how to serve his country when I find him, and as for you, old man, long enough have you hampered the King’s service.”

He pointed the weapon at Mr. Langston, when with a cry Dicey threw her arms about her father’s neck, and, shielding him with her body, called out over her shoulder,—

“Coward, shoot now if you dare!”

Bloody Bates, for indeed it was he, raised his pistol once more, and with a wicked scowl was preparing to fire, when one of the men who had stood silently by till now knocked up the weapon, saying,—

“As long as the cub we came for has fled, let us on, Bates. We have no war with dotards and children.” The others murmured surly assent, and bidding Dicey and her father beware how they harboured traitors, the whole party withdrew.

It took Dicey scarce a moment to fly to the door and bar it, and then hurry back to her father, who was lying back in his chair, pale with the excitement and the peril which they had undergone, and only too thankful that one among the company had respected his grey hairs and Dicey’s youth.

For many a day they lived in hourly fear of their lives, even after Bloody Bates had taken himself off on his raids and the neighbourhood was comparatively peaceful.

Did Dicey undergo any more special perils, you ask?

Yes; once again she faced grave danger, being met by a scouting party as she was coming from a trip to the nearest town. They questioned her as to the whereabouts of her brothers and other Whigs in the vicinity, but she refused to tell what she knew. The leader threatened to shoot her, but she faced him bravely, crying,—

“Well, here am I; shoot!” opening her neckerchief at the same time. He was ashamed apparently, for the band rode on, leaving her to make her way home.

She lived to see all her brothers but one return from their duties in the army, and by her loving care and devotion made her father’s life a happy one. She was only a little Southern girl living in a lonely spot, and long since dead; but her courageous acts live on and shine, as do all “good deeds in a naughty world.”