CHAPTER XIII.

THE DIAMOND RING.

The short days of the girls’ visit flew by on wings.

“Only till to-morrow!” sighed Cricket, as they got up from the luncheon table. “This time to-morrow you’ll be gone, and we’ll be left forlorn! I wish people who come here to visit would stay for always, and never go away.”

“What an India-rubber house you’d have to have,” said Archie, sweeping all her curls over her face with a nourish of his arm, as he passed her.

“Archie, when you get to heaven, you won’t be happy unless you can muss my hair up,” said Cricket, resignedly, shaking it back.

“Don’t get riled, Miss Scricket,” returned Archie, whirling her around. “That’s only a love-pat.”

“A love-pat!” said Cricket, scornfully. “I shouldn’t like to feel one of your hate-pats, then. Mamma, what can Hilda and I do this afternoon?”

“We girls are going to the museum again,” said Eunice. “Come with us.”

“No, we don’t want to. You like to see such disinteresting things. Mummies and all that. I only like the pictures and marbles, anyway.”

“We want something very nice,” put in Hilda, “because we kept house all day yesterday, and did very hard work.”

“Yes,” sighed Cricket, “I’ve learned two things lately. I don’t want to adopt a baby and have it keep me awake at night, and I don’t want to be poor and not have any books to read. Mamma, what can we do?”

“There is one thing I want you to do,” said mamma, promptly, knowing by long experience that when children are begging for something to do, nothing seems very attractive, if offered as a choice. The same thing, given as something from which there is no appeal, will be done cheerfully.

“I want you both to go and see Emily Drayton for a little while this afternoon. It is Hilda’s last chance. Eunice and Edith went yesterday. Go about three o’clock. She’ll be delighted to see you, if she is at home.”

“That will be jolly. I hope she’ll be in. Must we make a regular call, mamma, or can we plain go and see her?”

“‘Plain go and see her,’” said mamma, smiling. “Only go and put on your Sunday dress. It will be more polite to dress especially for it,” added wise mamma, knowing the process of dressing would help fill up the afternoon. Papa had planned to take all the children for a long drive this afternoon, but as he was unexpectedly called away, it had to be given up, and the girls were thrown on their own resources.

At three, the two younger girls, in their Sunday best, started in high feather for their call. It was a long walk to Emily Drayton’s, but the children enjoyed the crisp, cold day and the brisk exercise. Unfortunately, when they arrived at their destination, they found that Emily was out with her mother, and would not be home till late in the afternoon. Therefore there was nothing to be done but to turn around and travel home again.

“This isn’t very exciting, after all,” said Cricket, mournfully. “Here it’s nearly four o’clock, and most of your last afternoon is gone already. What let’s do next, Hilda?”

“Oh, I don’t know. I wish we’d gone to the museum with the girls. What’s the matter, Cricket?”

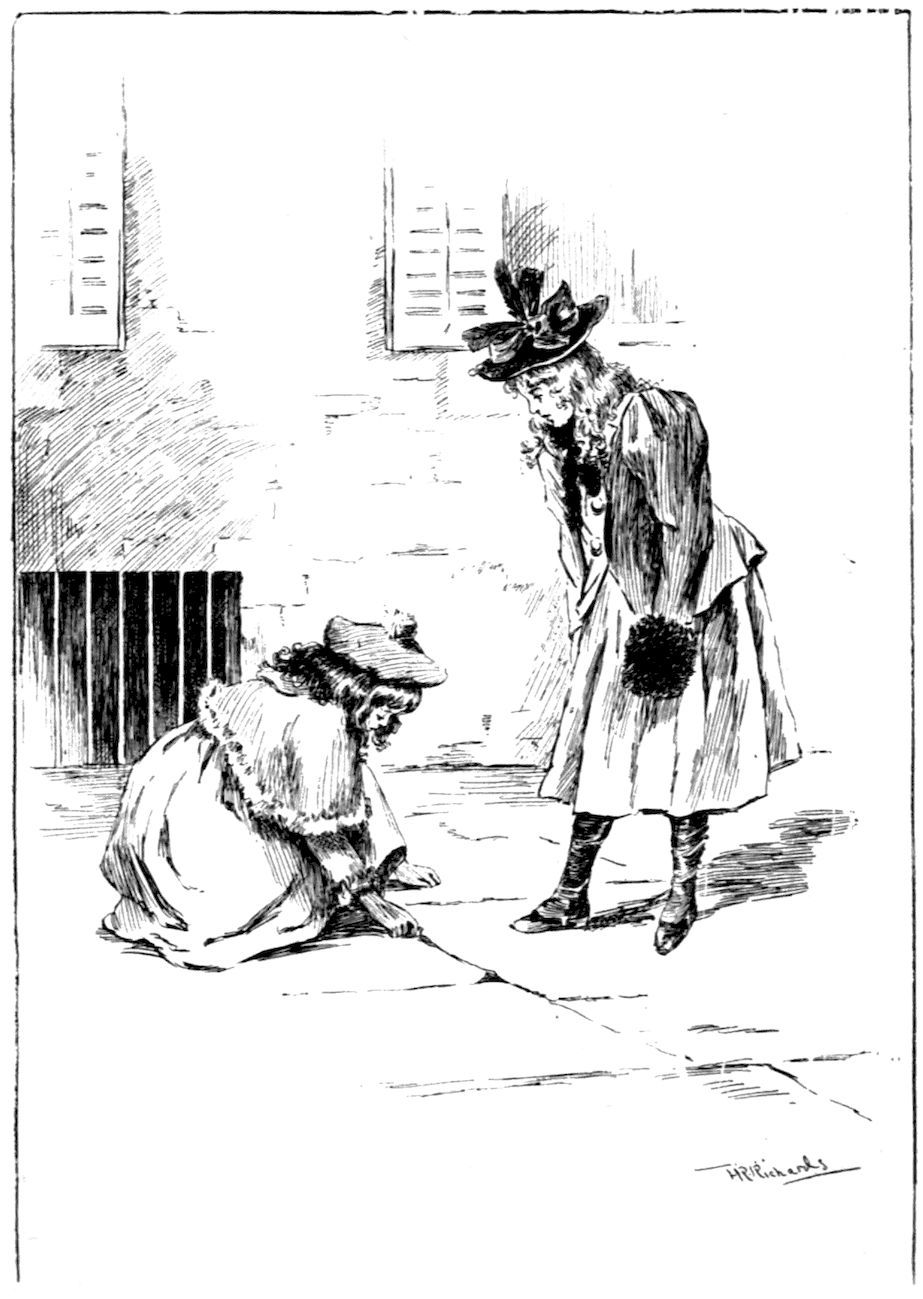

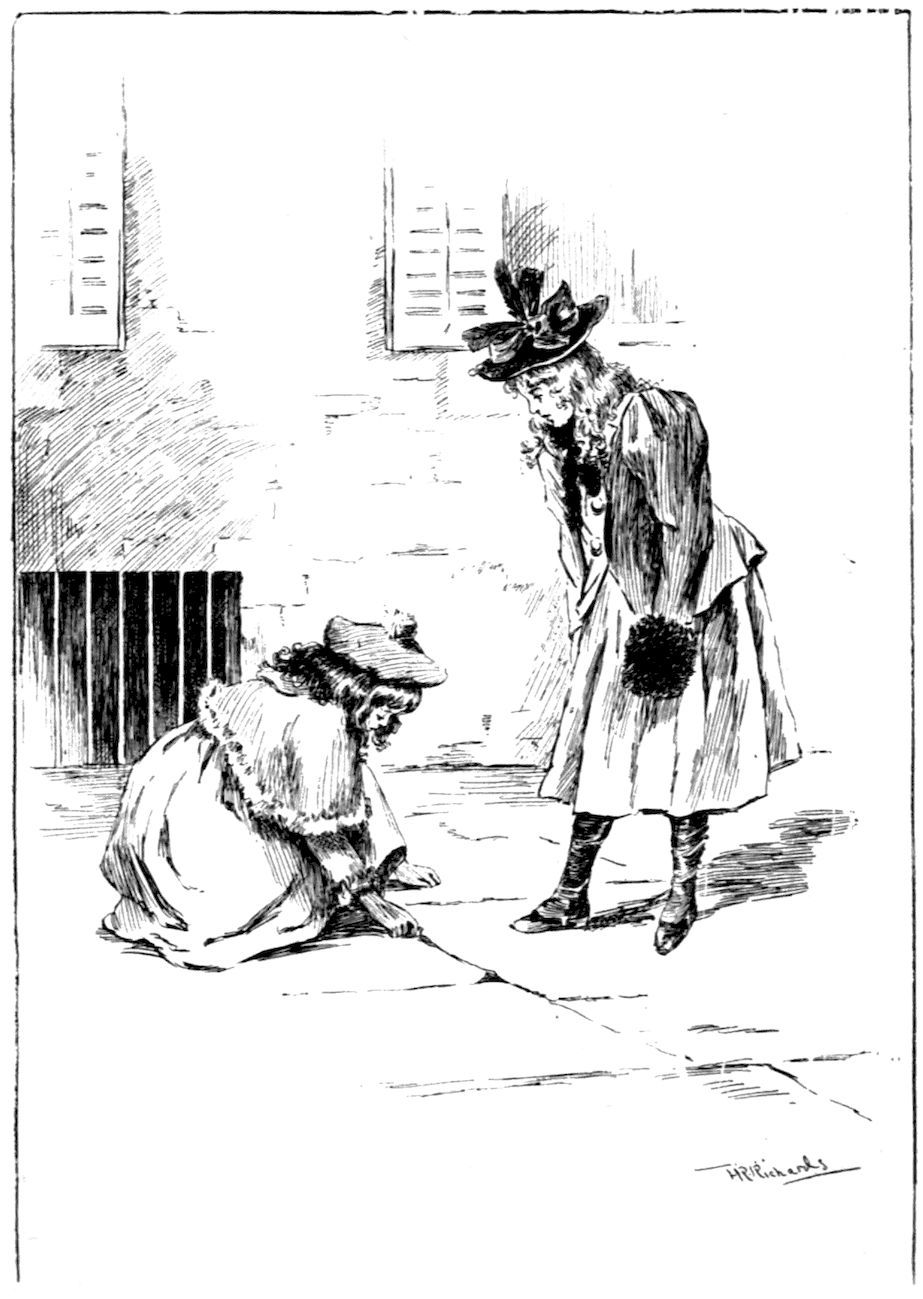

Cricket had suddenly stopped, and was poking at a crack in the sidewalk.

“I thought I caught a glimpse of something shiny in that crack. I did! See, Hilda!” and Cricket extricated something, triumphantly, and held it up.

Her own amazement grew as she looked.

“What? Not really, Cricket?” cried Hilda, and the two heads clashed over the treasure-trove.

It was a ring with a fairly good-sized diamond.

Cricket whooped, there and then, in her excitement. Fortunately the street was a quiet one, and no one was near.

“A diamond ring, Hilda! A really, truly diamond! Hooray! It’s as big as the one papa gave mamma on her birthday. I wonder if he’ll let me wear it.”

“But somebody has lost it,” said Hilda, in her practical way. “You’ll have to find the owner.”

THE DIAMOND RING.

“Why, so I will! How silly of me. I suppose papa will advertise it. It’s just like our finding Mosina; we never thought that somebody owned her. Let’s hurry home and show papa.”

The children skipped home briskly, in the excitement of so great a discovery, and burst into Doctor Ward’s office eagerly. He had just come in for something he needed, and was on the point of going out again.

“Found what? A diamond ring?” he asked, putting down his hat, and taking the ring that Cricket put in his hand.

“H’m. Where did you find this?” he asked, turning it to the light.

Cricket told him about it. Doctor Ward, as he listened, took down a tiny vial from one of his shelves, and put a drop of its contents on the ring, watching the effect.

“It’s gold, but I’m a little uncertain about the diamond,” he said. “It’s not worth advertising, if it’s not real,” he said, putting back the bottle. “You may take it to the jeweller’s, if you like, and get his opinion.”

“Not a diamond?” cried the disappointed children, in a breath.

“I think it’s only paste, my dear. However, you can run around to the jeweller’s and find out. I must go now.”

“Oh, dear me!” sighed Cricket, sorrowfully; “I thought we surely had found some excitement. Well, come on, Hilda; let’s go to Spencer’s and find out. If it isn’t a real diamond, may we have it, papa?”

“Yes,” answered Doctor Ward, absentmindedly, turning to find something else he wanted.

At Spencer’s the clerk took the ring with a smile.

“No, it isn’t a diamond,” he said, after giving it a careless glance. “Found it? No, it isn’t worth advertising.”

The two girls, who had still clung to the hope that they had found a diamond, looked immensely disappointed at this decision. They took the ring and walked slowly homeward, discussing the affair.

“If it isn’t a real diamond, and if it isn’t worth advertising, we might sell it for what it is worth,” suggested Hilda, brilliantly, at last. “Let’s go into the first jeweller’s store we come to, and ask him to buy it.”

“Could we?” said Cricket, doubtfully. “Is it ours enough for that?”

“Of course, goosie. Your father said we might have it, didn’t he? Of course we have a right to sell it and keep the money. He wouldn’t care,” urged Hilda.

“No, I s’pose not,” returned Cricket, hesitating. “How much do you suppose we’d get for it?”

“Oh, twenty or thirty dollars, I suppose, or something like that. Rings cost a lot,” answered Hilda, vaguely. “What shall we do with the money?”

“Buy a bicycle,” said Cricket, promptly. “Let’s each buy one. I’m crazy for a ‘bikachine,’ as Kenneth says.”

“So am I. What kind would you get?”

“They say the Humber is a pretty nice wheel,” said Cricket, reflectively; “but I guess that they cost too much, for I heard Donald say that he wanted one but couldn’t afford it. Perhaps we couldn’t get one of them, but we might each get a Columbia. Archie and Will have Columbias. Do you know how much they cost?” asked Cricket, who never had any more idea of the value of things than a cat. She had probably heard the price of a good bicycle mentioned scores of times, without its making the slightest impression upon her. Hilda, who, living alone with her mother and grandmother, never heard bicycles talked about, really did not know.

“I think the Columbias would do for us to learn on,” she said, patronisingly. “You can’t ride, can you?”

“Yes, I learned last fall on some of the girls’ wheels at school. It’s just as easy as pie. It’s so funny that people make so much fuss about learning. I like a boy’s wheel best, though. Wish I was on one this minute,” said Cricket, with a little skip.

“Now what else shall we get with the rest of the money?” asked Hilda.

“A bicycle for Eunice,” answered Cricket immediately. “Of course, mine would be part hers, but we couldn’t both ride at a time, unless I hung on behind, somehow. I suppose I might get a tandem.”

“Then you never could ride without somebody on behind,” said Hilda, sensibly; “and you might not always want it. No, I’d get a single wheel, if I were you. I think I’ll get a gold thimble with the rest of my half of the money.”

“I want a lot of new books,” said Cricket, characteristically. “I wish somebody would invent a book, that as fast as you read it would turn into another book that you haven’t read. Then you’d always have a new book to read. Will you get anything else?”

“I want a lot of things more, but I guess I’ll put the rest of my money into the savings bank. I’ve got three hundred dollars in the savings bank already.”

“I tried to make money, once, to buy a bicycle,” said Cricket, meditatively. “I had a store on the dock at Marbury for one day. Sold peanuts and lemonade. It was pretty tiresome though, and I didn’t make very much. Auntie said I didn’t make anything, but I never could understand it, somehow. I had twenty-one cents to put in my bank at night. I had fifty cents in the morning, but we spent it buying things to sell. Business is so queer. I should think men’s heads would burst, finding out whether they are making money or losing it.”

“It’s a great deal nicer not to make money, but have somebody leave you plenty, then you don’t have to bother,” said Hilda. “Here’s a store; let’s go in here.”

The two little girls marched up to the first clerk they saw.

“We want to see if you’ll buy this ring of us,” said Cricket, holding it out. “We want to sell it, please, and please give us all you can for it.”

The clerk stared and smiled.

“I’ll have to see the old gentleman about buying the ring,” he said. “You wait here a moment,” and with that he went off with the ring, leaving the children looking after him hungrily, and a little uncertain whether they would see their treasure again. However, the clerk returned in a moment.

“Mr. Elton says he can’t buy it unless you bring a note from your father or somebody, saying it’s all right about your selling the ring, for he doesn’t want to be let in for receiving stolen property.”

The clerk meant this for a joke, but the horror-stricken children did not understand this kind of humour.

“I said I found it,” said indignant Cricket at last, finding her voice.

“Oh, it’s all right, I dare say,” said the clerk carelessly; “you run along and get a note from somebody, and that will do.”

The children walked out of the store in a state divided between indignation and bewilderment.

“I said I found it,” repeated Cricket. “I don’t see what he wants a note for.”

“Let’s go somewhere else and sell it, and then they’ll be sorry,” said Hilda, tossing her head.

“Yes, we’ll go somewhere else, but first we had better go home and get a note from papa. Somebody else might ask for one,” returned Cricket, learning wisdom by experience. “You see, papa said we could have it if it wasn’t a real diamond, and it isn’t.”

They rushed up to the library and to the office, but papa was still out, and would not be back until dinner-time, the waitress told them. Then they went for mamma, but she had not returned either.

“Let’s write a note ourselves,” said Hilda. “Any kind of a note will do, I suppose. You see, it’s really ours. Your father said so.”

“Yes, I suppose it is. What shall we say? Let’s make up something.”

“All right! You take the ring,—now give it to me, and I’ll put in the note that a friend gave it to me, and I don’t like it, or something, and that we want to sell it. That will be regularly story-booky.”

After much writing and giggling and rewriting, the following note was concocted:

Dear Sir: I received this ring from a friend and it’s too big for me, and I send my daughter with it; and what will you give me for it?

Your friend,

J. JONES.

The “J. Jones” was actually a flight of fancy on Hilda’s part. She thought it would be still more “story-booky” to sign an assumed name, and Cricket finally consented.

“It looks very well,” said Cricket, surveying the effusion with much pride, when it was neatly copied in Hilda’s pretty writing on mamma’s best note paper. “And ‘J. Jones’ might be anybody, you know. Oh, Hilda! I hope we’ll get lots of money for it!”

“We ought to. The gold is worth a good deal, I suppose.”

“When we get the money, we might go straight down to the bicycle place, and buy a bicycle right away, this very day,” proposed Cricket, with a skip of delight, as the children went out again. “Just think of calmly walking into the house at dinner-time, with a bicycle under our arms! I mean, of course—well, you know what I mean.”

“Wouldn’t everybody be surprised? Where will you keep your wheel, Cricket?”

“In the basement hall, probably. What shall you name yours, Hilda?”

“Name it?” queried Hilda.

“Yes. I don’t see why they shouldn’t be named as well as a horse. Don’t you think Angelica is a good name? Oh, bicycle, so nice and dear! I wish you were this minute here! Why, that’s a rhyme, isn’t it?”

“Here’s a jeweller’s,” said Hilda, glancing at the window of a store they were passing. “It isn’t very big, but it looks pretty nice.”

A clerk with very black hair and a very big nose came forward to wait on them.

Cricket produced the ring for his inspection.

“It isn’t a really-truly diamond,” she said, lifting her honest eyes to his face, “but we’d like to sell it for what it’s worth. And here’s a note,” she added, producing it with a fluttering heart. Would he just say it was a joke, and not do anything about it? They waited breathlessly.

“Not a diamond?” said the clerk, taking it carelessly. He turned it over and looked at it closely, glanced at the children, read the note, and then said:

“No, it isn’t a diamond. I should say not. We’ll give you—let me see—well, I’ll have to ask the boss,” and he went off.

“They always have to ask somebody. Oh, Hilda, how much do you think they’ll give?” whispered Cricket, eagerly, squeezing Hilda’s hand.

“Probably thirty dollars, at least,” answered Hilda, returning the squeeze. “Hush! here he comes.”

“Boss says,” began the clerk deliberately, “that the diamond isn’t real, but if it’s all right about the note,”—the children gasped,—“that he can allow you, well, as much as seventy-five cents for the ring.”

Two wide-open mouths was all the clerk could see as he glanced down. The children were too amazed to speak for a moment.

“Seventy-five cents!” faltered Cricket, at last.

“Seventy-five cents!” echoed Hilda, blankly.

And they turned and stared at each other, not knowing what to say next.

“Come, do you want it?” asked the clerk, yawning. “Don’t be all night about deciding.”

“Is—is that all it’s worth?” at last ventured Cricket, her round little face really long with the disappointment.

“Really, now, that’s a pretty liberal offer,” said the clerk, assuming a confidential air. “Come, decide,” tapping the ring indifferently on the counter.

“Wouldn’t any one give me any more for it?” persisted Cricket.

“Hardly think it. Why, like as not the next person you go to might not offer you a cent more than fifty. We always do things of honour here. Liberal old bird, the boss is,” with a sly wink that half frightened the children. “Highest prices paid here for second-hand jewelry. Don’t you see the sign?” with a backward wave of his hand toward a placard on the wall.

Hilda and Cricket exchanged glances. Hilda nodded, and Cricket said, with a sigh that came from her very boots:

“Very well, we’ll take the seventy-five cents, if that’s all you can give us for it.”

“Positively all. Fortunate you came here, or you wouldn’t have gotten that,” said the clerk, counting out three new quarters into Cricket’s hand.

“Shine’s thrown in,” he said, facetiously, as the children soberly thanked him and walked out of the store, feeling very uncomfortable somehow.

“What a horrid man!” exclaimed Cricket, as they reached the sidewalk and drew a long breath. “Wasn’t he the most winkable creature you ever saw? I suppose he thought he was funny.”

“Greasy old thing!” returned Hilda, both children being glad to vent their disappointment on some convenient object. “His finger-nails were as black as ink.”

But Cricket could not stay crushed long. In a moment the smiles began to creep up to her eyes, and spill over on to her cheeks, and finally reached her mouth.

“Oh, Hilda! it’s too funny,” she cried, with her rippling laugh. “We were going to take our bicycles home under our arms all so grand! Shall we order them to-night?”

“I’m just too mad for anything,” answered Hilda, whose sense of humour never equalled Cricket’s. “Seventy-five cents! the idea! for that beautiful gold ring!”

“I’ve another idea,” said Cricket, stopping short suddenly. “It isn’t worth putting seventy-five cents in the bank, is it? Let’s stop at that old peanut-woman’s stand and get some peanuts with the money. I think we’ll get a good many for seventy-five cents.”

And they certainly did. The old woman stared at the munificent order, but began to count out bags with great speed, lest they should change their minds.

“Five cents a bag,” she said; “seven—eight—that makes quite a many bags—nine—ten—where will I put this?—eleven—twelve—here, little miss, tuck it in here,—thirteen—can you hold it up here?”

“We have enough, I think,” said Cricket, rather amazed at the quantity of peanuts you can get for seventy-five cents.

“That ain’t but thirteen, honey. Here, put this ’un under your arm. Got to go fur?”

“Not very. Well, Hilda, I never had all the peanuts I wanted at one time before, I do believe. I should think these would last a year. Oh, that one’s slipping off! Fix it, please. Thank you, ever so much.”

“Hollo, Madame Van Twister! Are you buying out the whole establishment?” said a familiar voice behind them, and turning they saw Donald.

“I guess she’s pretty glad to sell out,” said Cricket, seriously. “I know, for I kept a peanut-stand once in Marbury; the one I was telling you about, Hilda. It wasn’t much fun. It looks so, but it isn’t.”

“Buying her out from philanthropic motives?” queried Donald.

“No, we’ve been selling diamond rings,” said Cricket, carelessly, “and we had a lot of money, so we thought we’d buy peanuts. Want a bag, Don? we have plenty.”

“You’re a regular circus, you kid,” laughed Donald. “Where do you get your diamond rings?”

Cricket told him the whole story. Donald laughed till he had to hold on to the peanut-stand.

“J. Jones! Well, you certainly showed great originality in the name!” he said. “Sorry I can’t escort you home, youngster, and carry a few dozen of those bags for you, but I’m due elsewhere,” and Donald went off, still laughing.

If you want to know whether the family had enough peanuts, I will simply remark that by bedtime, that night, there were only two bags left,—and shells.

“After all, we girls didn’t eat so many,” said Cricket, meditatively. “Will and Archie ate ten bags. I counted. Boys are so queer! The more they eat, the more they want.”

Doctor Ward was out to dinner, and did not hear the end of the story of the ring till the next day.

“Do you mean you actually sold it, you little Jews?” he said. “Then I shall be obliged to go and buy it back.”

“Papa! why, we’ve spent the money!” cried Cricket, alarmed. “Besides, you said we could have it, didn’t you? I thought we could do anything we liked with it,” entirely forgetting that the proposition to sell it had not come from her.

“I believe I did say something about your having it if we couldn’t find an owner, or if the diamond was not real. However, I want to be sure on that point for myself. Sometimes mistakes are made. I must see about it.”

“Suppose they won’t sell it back,” suggested Cricket, looking uncomfortable.

“Perhaps they won’t, but I think I can induce them.”

“But we haven’t the seventy-five cents,” repeated Cricket, piteously, “and we’ve eaten up all the peanuts, so we can’t send them back and get the money.”

“Where are the peanuts, which we got for the seventy-five cents, which we got for the diamond ring, which we found on the street! Now, Miss Scricket, you’ve got to go to jail,” said Archie, cheerfully. “Where is the jail, which holds Miss Scricket, which ate the peanuts, which cost seventy-five cents, which she got for a diamond ring, what belonged to somebody else! Regular House that Jack Built.”

“You can pay for the peanuts you ate, then,” retorted Cricket. “That will be pretty nearly seventy-five cents.”

“That identical seventy-five cents it will not be necessary to return,” said Doctor Ward, pinching her cheek. “I’ll supply the money, and report at luncheon.”

At luncheon Doctor Ward held up the ring.

“I went, I saw, I got the ring, after an hour’s hard work. I suspected it was really a diamond as soon as the old Jew opened his lips.”

“It is a diamond?” cried every one, in chorus.

“I won’t keep you in suspicion, as Cricket used to say. It is a diamond, though not of the first water. The old fellow first pretended he knew nothing about the matter. I had the clerks called up. He only had two. One of them—”

“Did he have a big nose?” interrupted Cricket, eagerly.

“And greasy hair and black finger-nails?” added Hilda.

“All those,” said Doctor Ward. “Well, it took an hour, but finally I got it back. Then I took it to Spencer’s—”

“The very place we went to,” interrupted Cricket again.

“Yes, and I happened to see the very clerk. The moment I held it out he looked surprised; I told him I wanted it tested,—not merely glanced at. He took it off, and came back, presently, looking very sheepish, and told me, as I said before, that it is a diamond, though not a very valuable one for its size.”

“Why didn’t he look at it more carefully at first?” asked Mrs. Ward.

“He said something about thinking it was a joke that the children were putting up, and—”

“As if we would put up a joke on a perfect stranger!” cried Cricket, indignantly.

“Of course not, pet, but he didn’t know that. It was no excuse for him, though. He should have given it the proper attention. However, we have the ring safe now, after all its adventures, and we’ll advertise it.”

“Papa,” asked Cricket, dimpling suddenly, “if nobody ever claims it, may I have it for my own,—not to sell it, I mean,—but just to wear it when I’m grown-up?”

“Can’t promise. You’d probably pawn it the first time you wanted peanuts,” teased Doctor Ward.

That was several years ago, but the ring, which is still in mamma’s jewel-box, is now called Cricket’s.