HANS IN LUCK

Hans had served his master seven years, and at the end of that time he said to him, “Master, my time is up; now I should like to go home to my mother, so give me my wages, if you please.”

His master answered, “You have served me faithfully and well, and as the service has been, so shall the wages be”; and he gave him a lump of gold as big as his head.

Hans pulled his handkerchief out of his pocket, wrapped the lump in it, slung it over his shoulder, and set out on the way home.

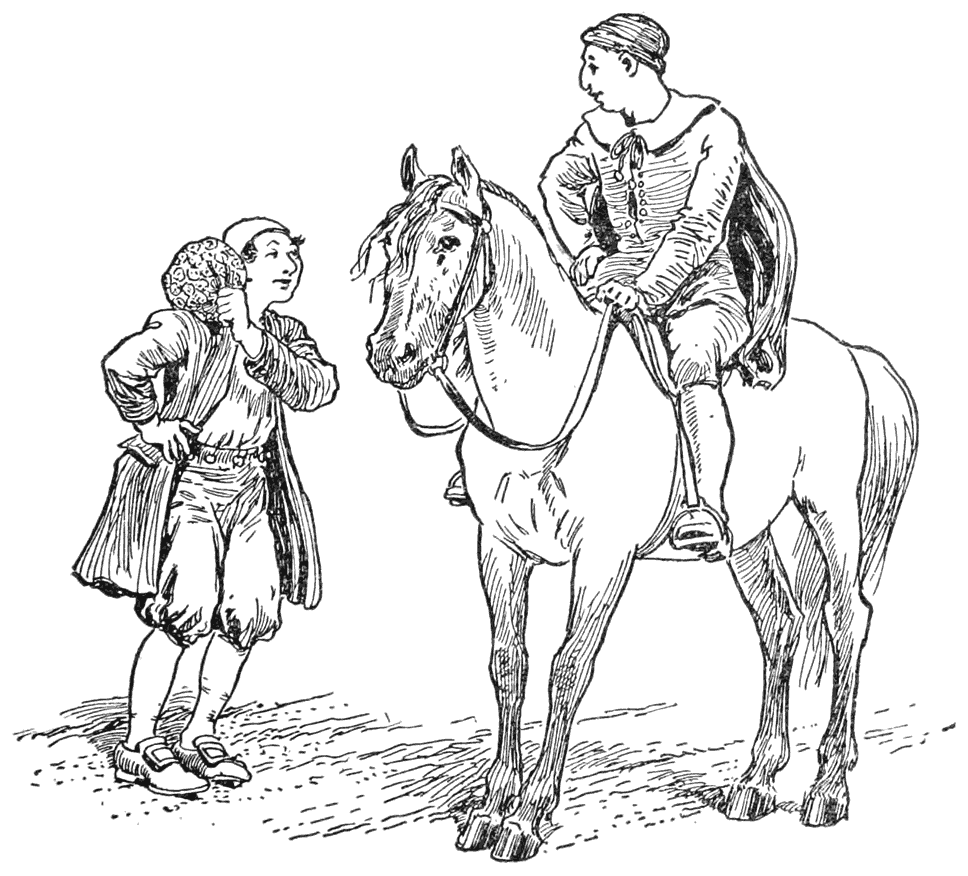

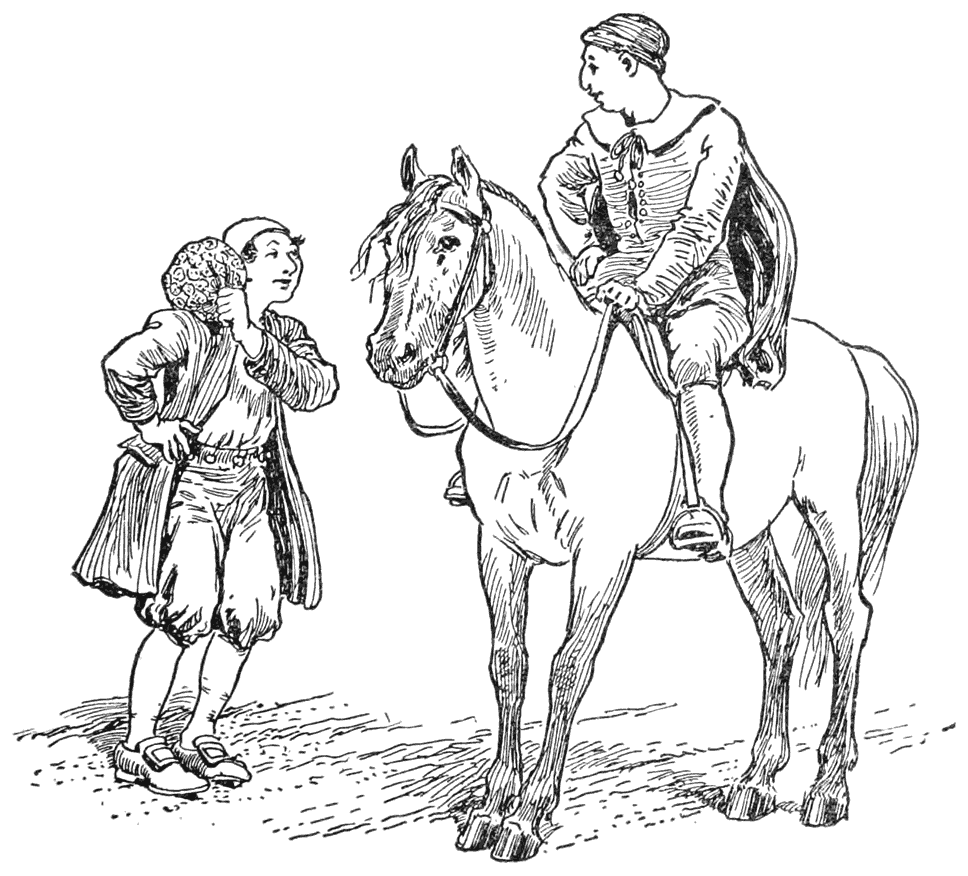

As he was trudging painstakingly and laboriously along the road a horseman came in sight, trotting gayly and briskly along on a spirited horse.

“Ah,” said Hans aloud, “what a fine thing riding is! There you sit as comfortable as in a chair; you stumble over no stones, you save your shoes, and you get over the ground you hardly know how.”

The horseman, overhearing him, stopped and said, “Halloo, Hans! Why do you go on foot then?”

“I can’t help it,” answered Hans, “for I have this bundle to carry home. It is gold, to be sure, but I cannot hold my head straight for it, and it hurts my shoulder, too.”

“I will tell you what,” said the horseman, “we will exchange. I will give you my horse, and you shall give me your lump.”

“With all my heart,” said Hans; “but I tell you beforehand that you are taking a good heavy load on yourself.”

The horseman got down, took the gold, and helped Hans up, putting the bridle into his hands, and said, “Now, when you want to go at a really good pace, you must click your tongue and cry, ‘Gee up! gee up!’ ”

Hans was delighted when he found himself sitting on a horse and riding along so freely and easily. After a while it occurred to him that he might go still faster, and he began to click with his tongue and cry, “Gee up! gee up!” The horse broke into a gallop, and before Hans knew what he was about he was thrown off and was lying in a ditch which separated the fields from the highroad. The horse would have run away if it had not been stopped by a peasant who was coming along the road and driving a cow before him. Hans felt himself all over, and picked himself up; but he was vexed, and said to the peasant: “This riding on horseback is no joke, I can tell you, especially when a man gets on a mare like mine, that kicks and throws one off, so that it is a wonder one’s neck is not broken. Never again will I ride that animal! Now I like your cow; you can walk quietly along behind her, and you have her milk, butter, and cheese, every day, into the bargain. What would I not give for such a cow!”

“Well, now,” said the peasant, “if it would give you as much pleasure as all that, I don’t mind exchanging the cow for the horse.”

Hans agreed to this with the greatest delight, and the peasant, swinging himself upon the horse, rode off in a hurry.

Hans drove his cow peacefully before him, and thought over his lucky bargain. “If I only have a bit of bread—and I ought never to be without that—I can have butter and cheese with it as often as I like; if I am thirsty, I have only to milk the cow and I have milk to drink. What more could heart desire?”

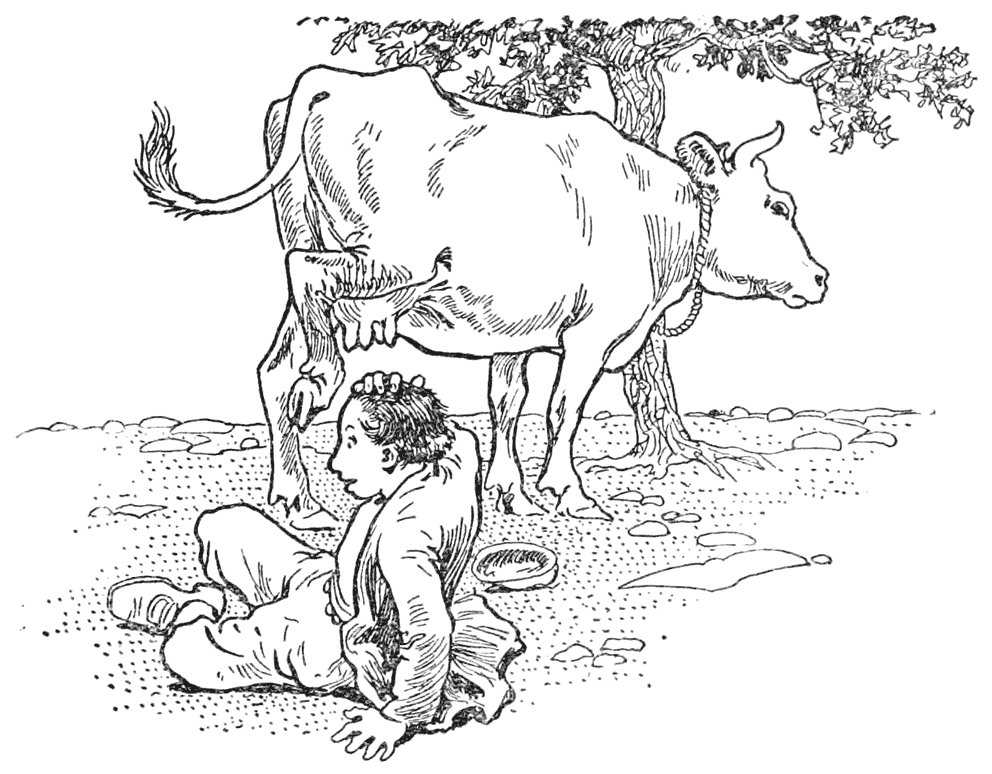

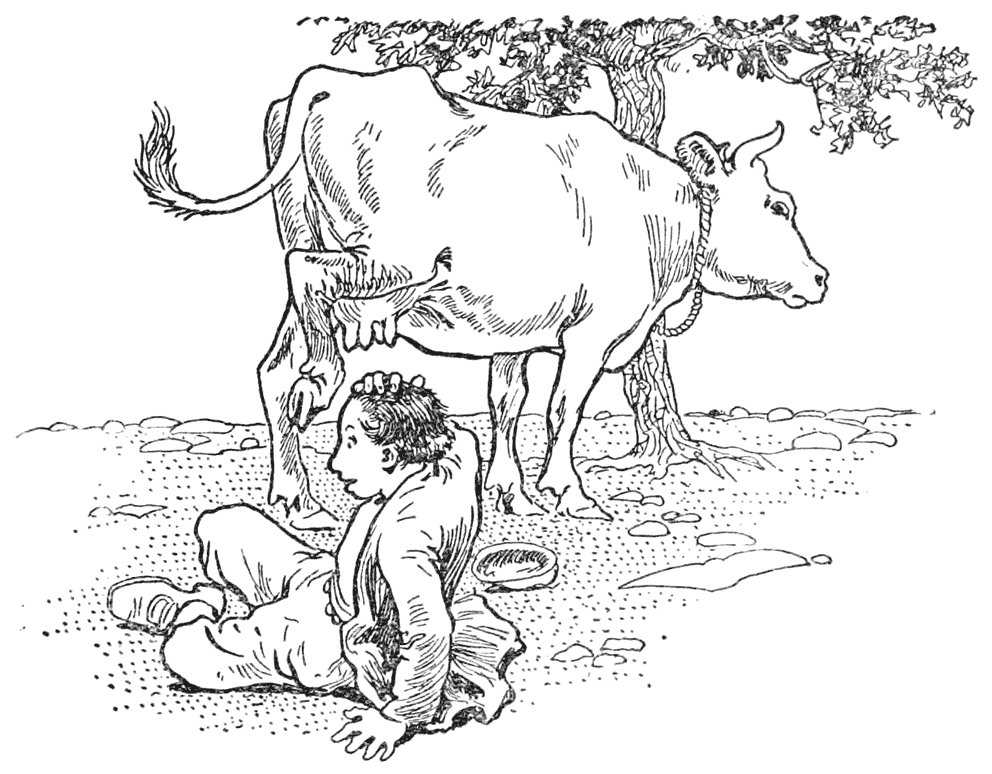

When he came to an inn he made a halt, and ate with great satisfaction all the bread he had brought with him for dinner and supper, and spent his last two farthings for a glass of beer to drink with it. Then he drove his cow along in the direction of his mother’s village. The heat grew more and more oppressive as the middle of the day drew near, and Hans found himself on a wide heath which it would take about an hour to cross. He was very hot and thirsty.

“This is easily remedied,” thought Hans; “I will milk the cow and refresh myself with the milk.”

He tied her to a tree, and as he had no pail he put his leather cap underneath her; but try as hard as he could, not a drop of milk came. He had put himself in a very awkward position, too, and at last the impatient beast gave him such a kick on the head that he tumbled over on the ground and was so dazed that for a long time he could not think where he was.

Fortunately a butcher came along soon, trundling a wheelbarrow in which lay a young pig.

“What’s the matter here?” he cried, as he helped Hans up.

Hans told him what had happened. The butcher handed him his flask and said: “There, take a drink; it will do you good. That cow might well give no milk; she is an old beast, and only fit at best for the plow or for the butcher.”

“Dear, dear!” said Hans, running his fingers through his hair, “who would have thought it! It is an idea to kill the beast and have the meat. But I do not care much for beef,—it is not juicy enough. Now a young pig like yours,—that is what would taste good; and then there are the sausages!”

“Take heed, Hans,” said the butcher; “out of love for you I will exchange and let you have the pig for the cow.”

“May Heaven reward you for your kindness!” cried Hans, handing over the cow as the butcher untied the pig from the barrow and put into his hand the string with which it was tied.

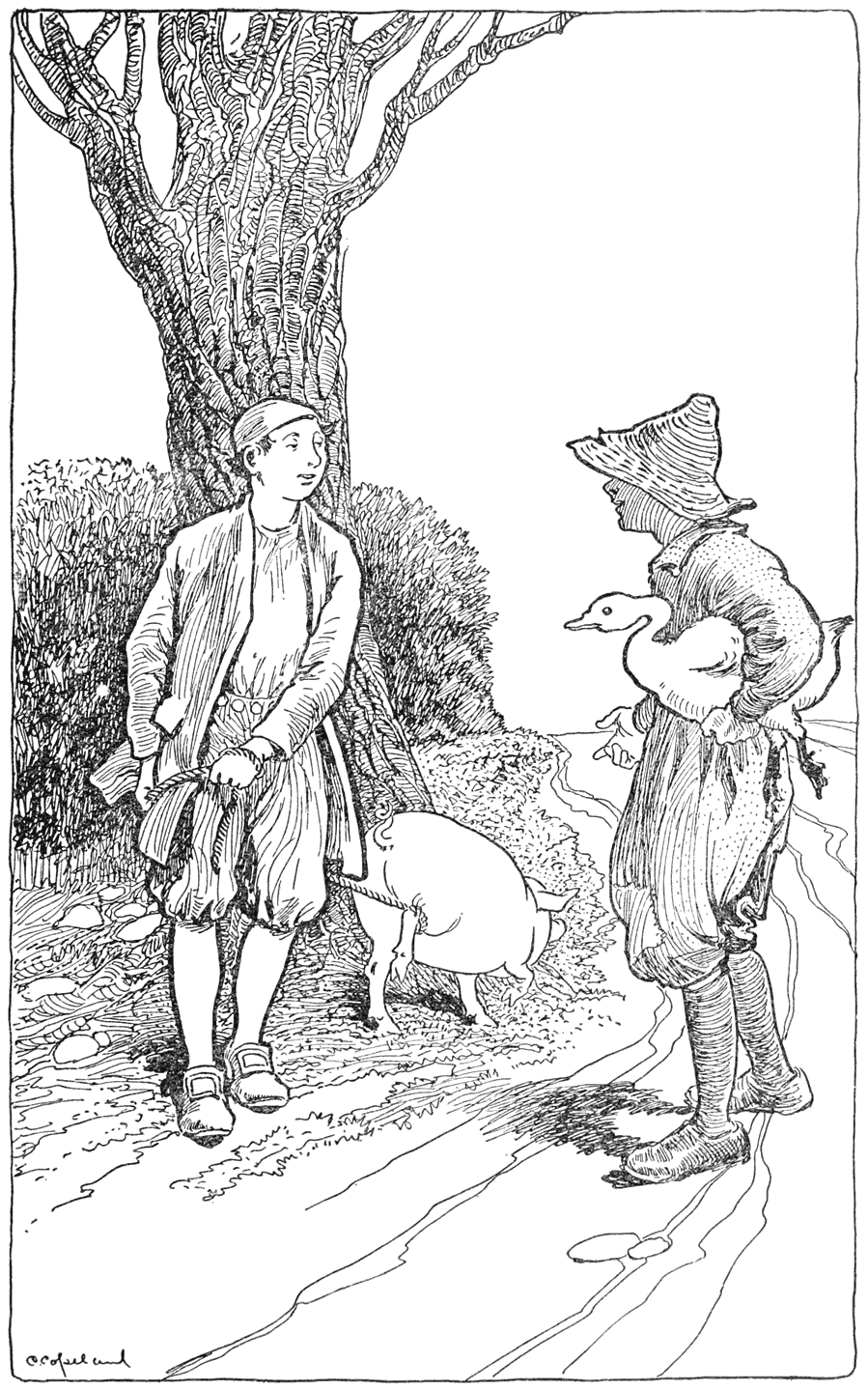

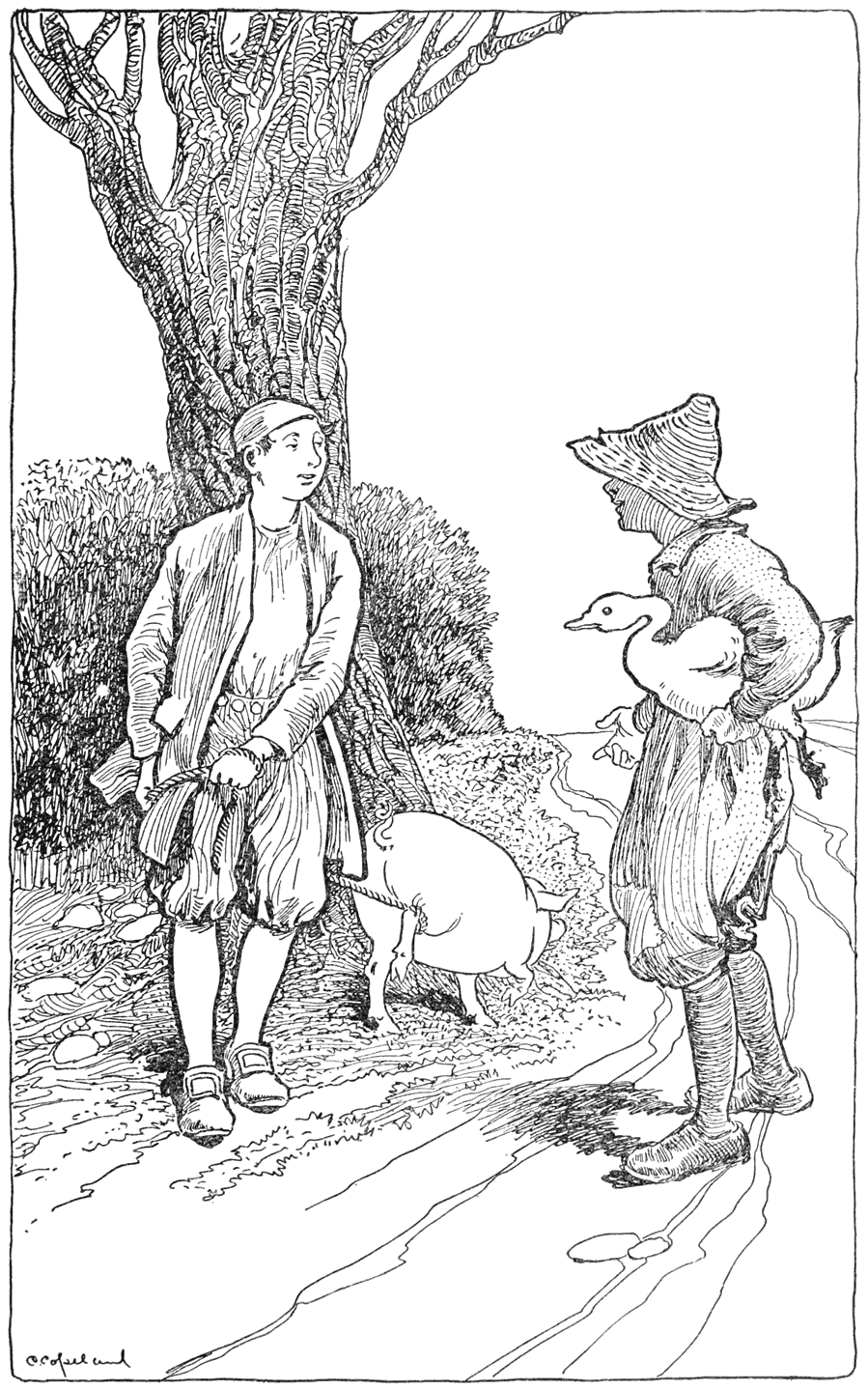

Hans went on again, thinking how everything was turning out just as he wished; if he did meet with any mishap, it was immediately set right. Presently a lad overtook him who was carrying a fine white goose under his arm. They said “Good morning” to each other, and then Hans began at once to tell of his good luck and how he always made such good bargains. The lad told him that he was taking the goose to a christening feast.

“Just lift it,” said he to Hans, holding it up by the wings, “and feel how heavy it is; it has been fattened up for the last eight weeks. Whoever gets a taste of it when it is roasted will get a rare bit.”

“Yes,” said Hans, weighing it in one hand, “it is a good weight, but my pig is no trifle either.”

Meanwhile the lad kept looking suspiciously from one side to the other and shook his head.

“Look here,” he began, “I’m not so sure it’s all right with your pig. In the village through which I passed, the mayor himself had just had one stolen from his sty. I fear—I fear you have got hold of it there in your hand. They have sent out people to look for it, and it would be a bad business for you if you were found with it; at the very least, you would be shut up in the dark hole.”

Honest Hans was very much frightened.

“Alas!” he said, “help me out of this trouble! You are more at home in these parts than I; take my pig and let me have your goose.”

“I shall run some risk if I do,” answered the lad, “but I will not be the cause of your getting into trouble.”

So he took the cord in his hand and drove the pig quickly away by a side path.

Honest Hans, relieved of his anxiety, plodded along towards home with the goose under his arm. “When I really come to think it over,” he said to himself, “I have even gained by this exchange: first, there is the good roast; then the quantity of fat that will drip out of it in roasting and will keep us in goose fat to eat on our bread for a quarter of a year; and last of all there are the fine white feathers, with which I will stuff my pillow, and then I warrant I shall sleep like a top. How delighted my mother will be!”

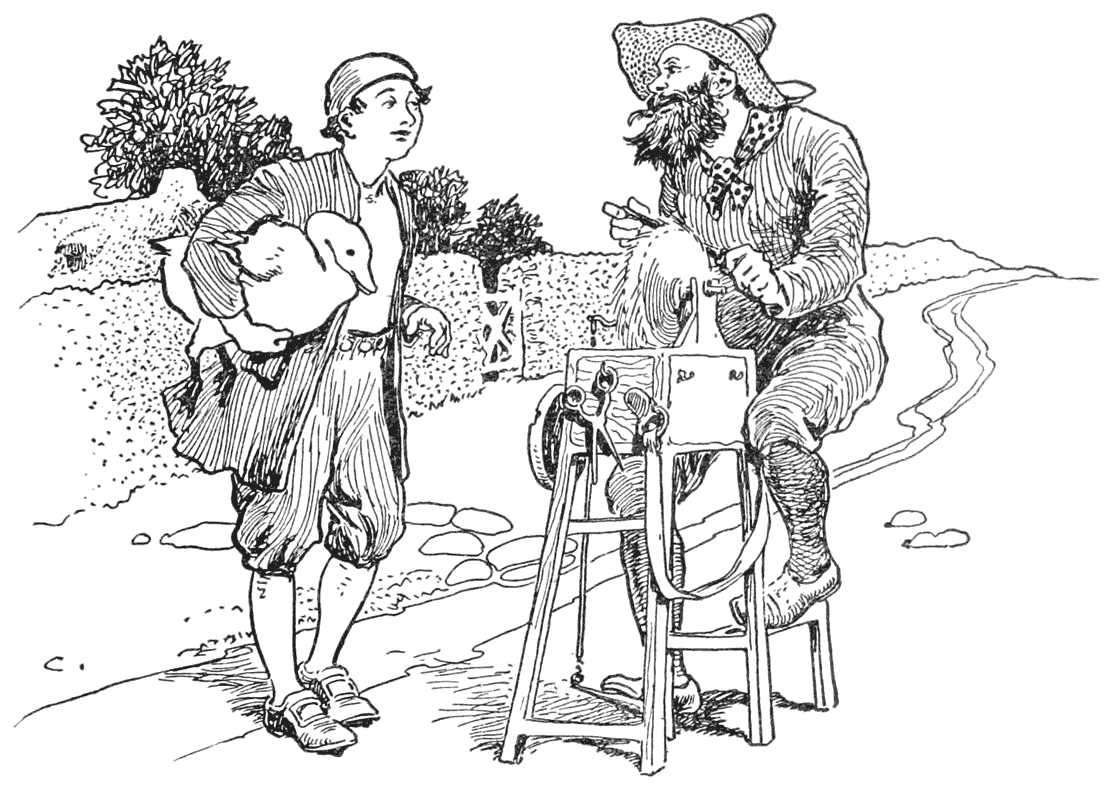

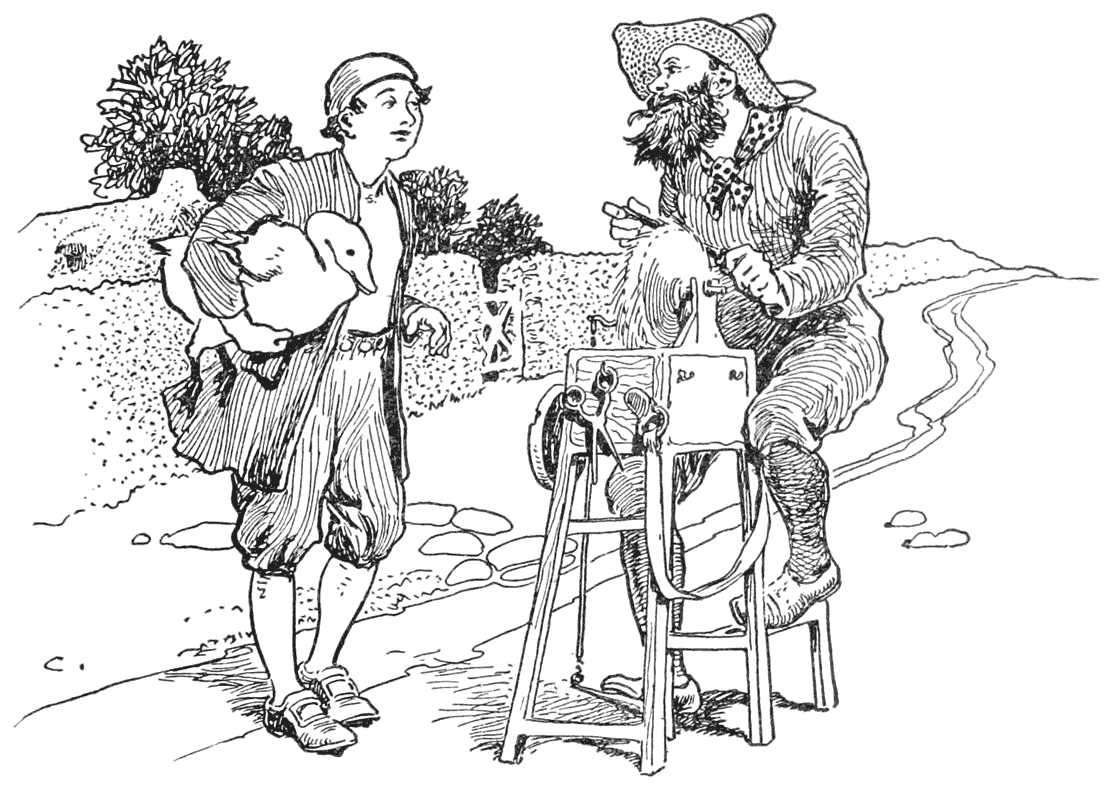

As he was going through the last village he came to a knife grinder with his cart, singing, as his wheel whirred busily around,

“Scissors and knives I quickly grind,

While my coat flies out in the wind behind.”

Hans stopped to watch him; at last he spoke to him and said, “You appear to have a good business, if I may judge by your merry song.”

“Yes,” answered the knife grinder, “this business has a golden bottom. A good grinder finds money in his pocket whenever he puts his hand in it. But where did you buy that fine goose?”

“I did not buy it, but took it in exchange for my pig.”

“And the pig?”

“That I got for a cow.”

“And the cow?”

“I took that for a horse.”

“And the horse?”

“For that I gave a lump of gold as big as my head.”

“And the gold?”

“Oh, that was my wages for seven years’ service!”

“You have certainly known how to look after yourself each time,” said the grinder. “If you can only get on so far as to hear the money jingle in your pockets whenever you stand up, you will indeed have made your fortune.”

“How shall I manage that?” said Hans.

“You must become a grinder, like me; nothing in particular is needed for it but a grindstone,—everything else will come of itself. I have one of those here; to be sure it is a little worn, but you need not give me anything for it but your goose. Will you do it?”

“How can you ask?” said Hans. “Why, I shall be the luckiest man in the world. If I have money every time I put my hand into my pocket, what more can I have to trouble about?”

So he handed him the goose and took the grindstone in exchange.

“Now,” said the grinder, picking up an ordinary big stone that lay by the road, “here is another good stone into the bargain. You can hammer out all your old nails on it and straighten them. Take it with you and keep it carefully.”

Hans shouldered the stones and walked on with a light heart, his eyes shining with joy. “I must have been born under a lucky star,” he exclaimed; “everything happens to me just as I want it.”

Meanwhile, as he had been on his legs since daybreak, he began to feel tired. He was hungry, too, for in his joy at the bargain by which he got his cow he had eaten up all his store of food at once, and had had none since. At last he felt quite unable to go farther, and was forced to rest every minute or two. Besides, the stones weighed him down dreadfully. He could not help thinking how nice it would be if he did not have to carry them any farther.

He dragged himself slowly over to a well in the field, meaning to rest and refresh himself with a draft of cool water. To keep the stones from hurting him while he knelt to drink, he laid them carefully on the edge of the well. Then he sat down, and was about to stoop and drink, but made a slip which gave the stones a little push, and both of them rolled off into the water. When Hans saw them sinking to the bottom he jumped for joy, and knelt down and thanked God, with tears in his eyes, for having shown him this further favor, and relieved him of the heavy stones (which were the only things that troubled him) without his having anything to reproach himself with.

“There is no man under the sun so lucky as I,” he cried out. Then with a light heart, and free from every burden, he ran on until he reached his mother’s home.