HOP-O’-MY-THUMB

Once upon a time there was a fagot-maker and his wife who had seven children, all boys. The eldest was but ten years old, the youngest only seven.

They were very poor, and their seven children were a great burden to them, because not one of them was able to earn his own living. What worried them still more was that the youngest was a delicate little fellow, who hardly ever spoke a word. They took for stupidity this silence, which was really a sign of good sense. He was tiny, too; when he was born he was no bigger than a man’s thumb, so they called him Hop-o’-my-Thumb.

The poor child was the drudge of the whole household, and always bore the blame for everything that went wrong. However, he was really the cleverest and brightest of all the brothers, and if he spoke little, he heard and thought the more.

There came now a very bad year, and the famine was so great that these poor people felt obliged to get rid of their children. One evening, when the children had gone to bed and the fagot-maker was sitting with his wife at the fire, he said to her, with his heart ready to burst with grief: “You see plainly that we can no longer give our children food, and I cannot bear to see them die of hunger before my eyes. I am resolved to lose them in the forest to-morrow. This may very easily be done, for while they are amusing themselves in tying up fagots we have only to slip away and leave them without their taking any notice.”

“Ah!” cried out his wife; “do you think you could really take out your children and lose them?”

In vain did her husband remind her of their extreme poverty, she would not consent to it; she was poor, but she was their mother. At last, when she reflected what a grief it would be to her to see them die of hunger, she consented, and went weeping to bed.

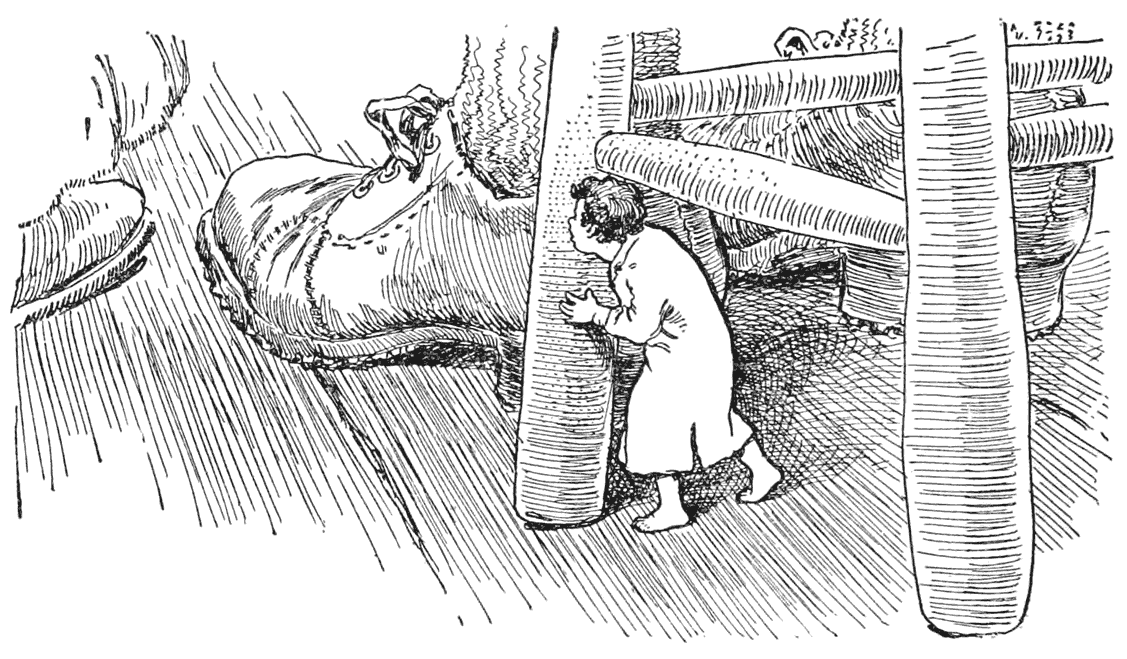

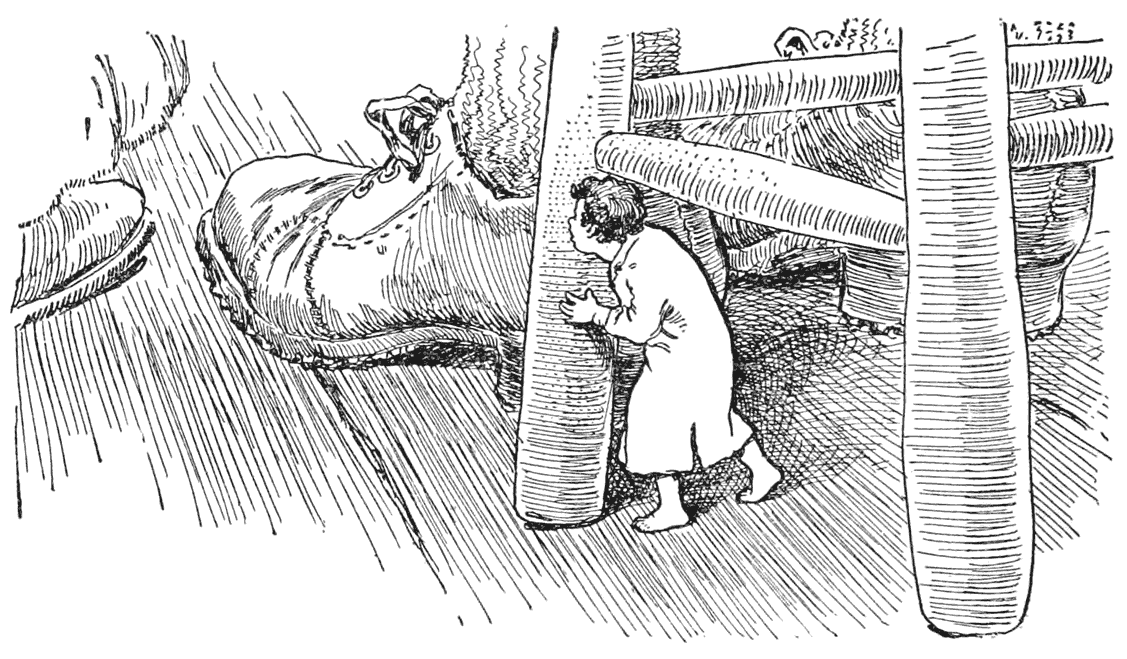

Hop-o’-my-Thumb heard all they had said; for when he heard, as he lay in bed, that they were talking of their affairs, he got up softly and slipped under his father’s stool, to hear without being seen. He went to bed again, but did not sleep a wink all the rest of the night, thinking of what he should do. He got up early in the morning, and went to the bank of a brook, where he filled his pockets full of small white pebbles, and then went back home.

They all set out, but Hop-o’-my-Thumb did not say a word to any of his brothers about what he had heard.

They went into a very thick forest, where they could not see one another ten paces apart. The fagot-maker began to cut wood, and the children to gather up the sticks to make fagots. When their father and mother saw them busy at their work, they slipped away from them little by little, and then made their escape all at once by a winding bypath.

When the children found that they were alone they began to cry bitterly. Hop-o’-my-Thumb let them cry on, knowing very well how he could get home again; for, as he came, he had dropped the little white pebbles he had in his pockets all along the way. Then he said to them, “Do not be afraid, my brothers; father and mother have left us here, but I will lead you home again,—only follow me.”

They followed him, and he brought them home through the forest by the very same way by which they had come. At first they dared not go in, but stood outside the door to listen to what their father and mother were saying.

Just as the fagot-maker and his wife reached home, the lord of the manor sent them ten crowns, which he had owed them for a long time, and which they had never expected to get. This gave them new life, for the poor people were almost famished with hunger. As it was a long while since they had eaten, the woman bought as much meat as would satisfy six or eight persons. When they had satisfied their hunger she said: “Alas! where are our poor children now? they would make a good feast of what we have left here. It was you, William, who wished to lose them; I told you we should repent of it. What are they doing now in the forest? Alas! perhaps the wolves have already eaten them up! You are very cruel to have lost your children in this way.”

The fagot-maker grew very impatient at last, for she repeated more than twenty times that they should repent of it, and that she had told him so. He threatened to beat her if she did not hold her tongue. The fagot-maker was, perhaps, even more sorry than his wife, but she teased him, and he could not endure her telling him that she was in the right all the time. She wept bitterly, saying, “Alas! where are my children now,—my poor children?”

She said this once so very loud that the children, who were at the door, heard her and cried out all together, “Here we are! here we are!”

She ran quickly to let them in, and said, as she embraced them: “How happy I am to see you again, my dear children! You must be very tired and very hungry. And you, little Peter, you are dirt all over! Come in and let me get you clean again.”

Peter was her eldest boy, whom she loved more than all the rest, because he had red hair like her own.

They sat down to table, and ate with an appetite which pleased both father and mother, to whom they told—speaking all at once—how frightened they had been in the forest. The good people were delighted to see their children once more, and this joy continued while the ten crowns lasted; but when the money was all gone they fell back again into their former anxiety, and resolved to lose their children again,—and that they might be the surer of doing it, they decided to take them much farther off than before.

They could not talk of this so secretly but that they were overheard by Hop-o’-my-Thumb, who counted on getting out of the difficulty as he had done before; but though he got up very early the next morning to go and pick up some little pebbles, he could not carry out his plan, for he found the house-door double-locked. He did not know what to do; but a little later, when his father had given each of them a piece of bread for their breakfast, it came into his head that he could make his bread do instead of pebbles, by dropping crumbs all along the way as they went, so he put it into his pocket.

Their father and mother led them into the thickest and gloomiest part of the forest, and then, stealing away into a bypath, left them there. Hop-o’-my-Thumb did not worry himself very much at this, for he thought he could easily find the way back by means of his bread that he had scattered all along as he came; but he was very much surprised when he could not find a single crumb,—the birds had come and eaten them all.

They were now in great trouble, for the farther they went the more they went wrong and the deeper they got into the forest. Night came on, and with it a high wind which frightened them desperately. They fancied they heard on every side the howling of wolves coming to eat them up. They hardly dared to speak or turn their heads. Then there came a heavy rain, which wetted them to the very skin. Their feet slipped at every step, and they fell into the mud, getting themselves so covered with dirt that they could not even get it off their hands.

Hop-o’-my-Thumb climbed to the top of a tree to see if he could discover anything. Searching on every side, he saw at last a glimmering light, like that of a candle, but a long way off, and beyond the forest. He came down, but when he was upon the ground he could not see it. This discouraged him very much; but finally, when he had been walking for some time with his brothers towards that side on which he had seen the light, he caught sight of it again as he came out of the wood.

They came at last to the house where this candle was, although not without many frights, for they lost sight of it every time they came into a hollow—which was very often. They knocked at the door and a kind woman came to open it. She asked them what they wanted, and Hop-o’-my-Thumb told her they had lost their way in the forest, and begged to stay and sleep there for charity’s sake. When the woman saw how pretty they were she began to weep, and said to them: “Alas, poor children, you do not know what kind of a place you have come to! Do you know that this house belongs to a cruel ogre who eats up little children?”

“Alas! dear madam,” answered Hop-o’-my-Thumb, who was trembling in every limb, as were his brothers, too, “what shall we do? The wolves of the forest will surely devour us if you refuse us shelter here, and so we would rather the gentleman should eat us. Perhaps he will have pity on us if you are so kind as to entreat him for us.”

The ogre’s wife, who believed that she could hide them from her husband till morning, let them come in, and had them warm themselves at a very good fire, before which a whole sheep was being roasted for the ogre’s supper.

As they were beginning to get warm, they heard three or four great raps at the door: this was the ogre, who was coming home. His wife hurried the children under the bed to hide them, and then went to open the door. The ogre at once asked if supper was ready and the wine drawn, and sat down at the table. The sheep was raw still, but he liked it all the better for that. But in a minute or two he sniffed about to the right and to the left, saying, “I smell fresh meat, I smell fresh meat.”

“What you smell,” said his wife, “must be the calf which I have just killed and dressed.”

“I smell fresh meat, I tell you once more,” said the ogre, looking crossly at his wife, “and there is something here which I do not understand.”

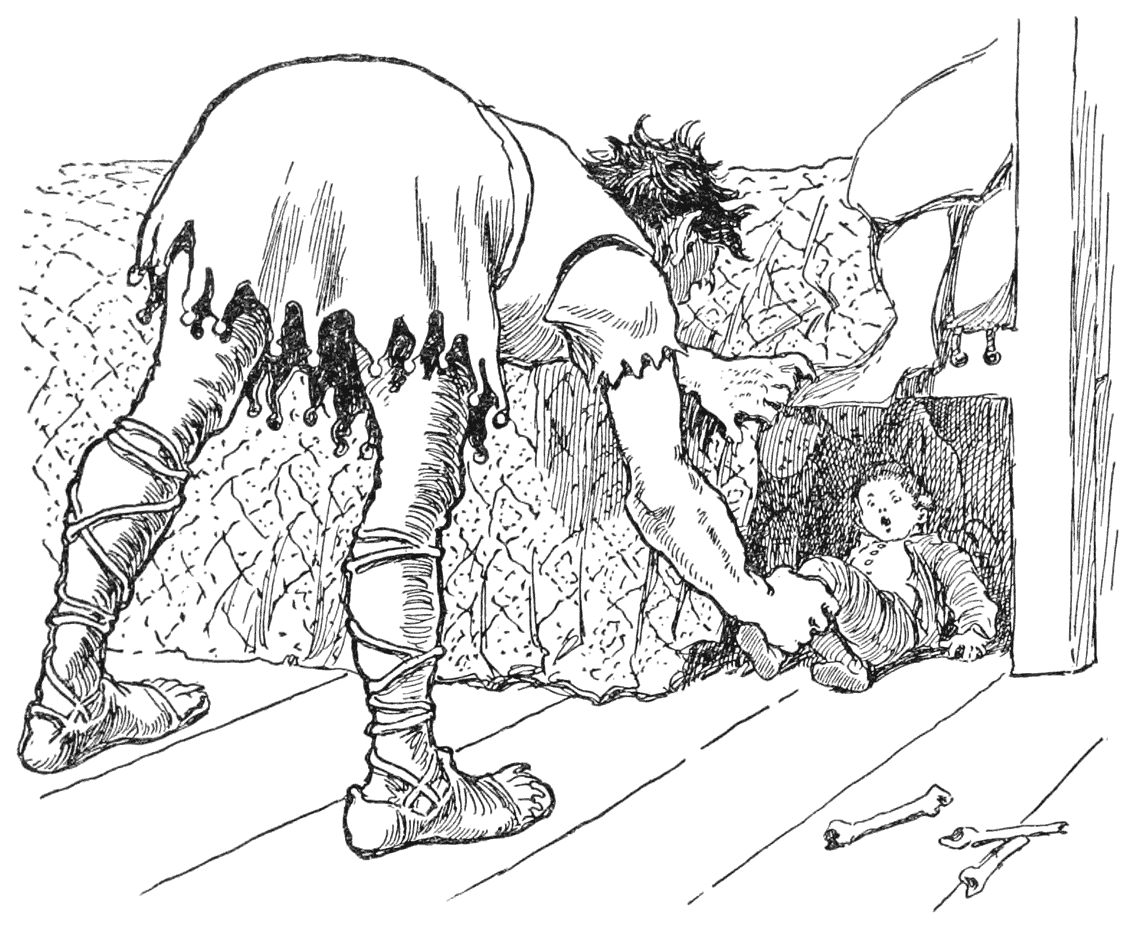

As he spoke these words, he got up from the table, and went straight to the bed.

“Ah,” said he, “that is how you thought to cheat me! Wretch! I do not know why I do not eat you up too; it is well for you that you are old and tough. Here is game which comes just in season to entertain three ogres, friends of mine, who are to pay me a visit in a day or two.”

With that he dragged them out from under the bed one by one. The poor children fell upon their knees and begged for pardon; but they had to deal with the most cruel of ogres, who, far from having any pity for them, had already devoured them with his eyes, and now told his wife they would be dainty morsels when she served them up with a good sauce.

He then fetched a great knife and began to sharpen it on a great whetstone which he held in his left hand; and all the while he came nearer and nearer to the poor children. He had already taken hold of one of them when his wife said to him: “Why do you need to do it at this time of night? Is not to-morrow time enough?”

“Hold your prating!” said the ogre; “they will grow more tender if they are kept a little while after they are killed.”

“But you have so much meat already,” replied his wife; “here are a calf, two sheep, and half a pig.”

“You are right,” said the ogre. “Give them all a good supper, that they may not get thin, and put them to bed.”

The good woman was overjoyed at this, and gave them a good supper; but they were so afraid that they could not eat a bit. As for the ogre, he sat down again to drink, well pleased that he had such a feast with which to treat his friends. He drank a dozen glasses more than usual, which went to his head and soon obliged him to go to bed.

The ogre had seven daughters, who were still little children. These young ogresses had all of them very fine complexions, because they ate raw meat like their father; but they had small gray eyes, quite round, hooked noses, wide mouths, and very long, sharp teeth, set very far apart from each other. They were not very wicked yet, but they gave promise of becoming so, for they had already bitten little children.

They had been put to bed early, all seven in one great bed, each with a crown of gold upon her head. There was another bed of the same size in the room, and in this the ogre’s wife put the seven little boys, and then went to bed herself along with her husband.

Hop-o’-my-Thumb took notice that the ogre’s daughters all had crowns of gold on their heads, and he was so afraid lest the ogre should repent his not killing them, that he got up about midnight, and, taking his brothers’ caps and his own, went very softly and put them on the heads of the seven little ogresses. But he first took off their crowns of gold, and put them on his own head and his brothers’, so that the ogre might take them for his daughters, and his daughters for the little boys whom he wanted to kill.

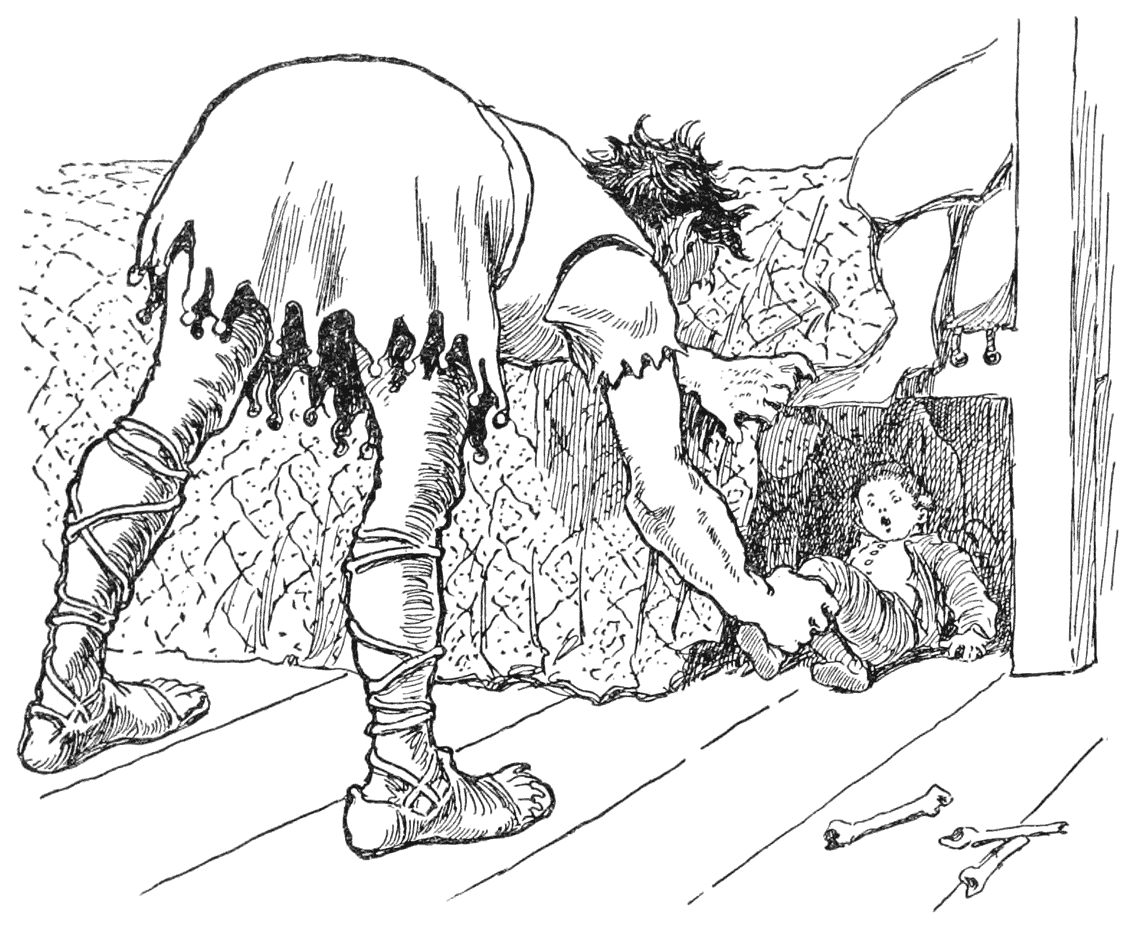

Everything turned out just as he had thought; for the ogre, waking about midnight, began to feel sorry that he had put off killing the boys till morning, when he might have done it overnight, so he jumped up quickly out of bed, taking his great knife.

“Let us see,” said he, “how our little rogues are getting on, and do the job up at once!”

He groped his way up to his daughters’ room, and went to the bed where the little boys lay, all fast asleep except Hop-o’-my-Thumb, who was terribly afraid when he found the ogre fumbling about his head, as he had done about his brothers’. When he felt the golden crowns, he said, “Truly, I should have done a pretty piece of work last night; it is perfectly evident that I drank too much wine then.”

Next he went to the bed where the girls lay, and when he felt the boys’ caps, he said, “Ah, my merry lads, here you are! let us get to work.”

And saying these words, without more ado he cut the throats of all his seven daughters. Well pleased with what he had done, he went back to bed again.

As soon as Hop-o’-my-Thumb heard the ogre snore, he waked his brothers and told them to put on their clothes quickly and follow him. They stole down softly into the garden and got over the wall. They ran almost all night, trembling all the while, and without knowing where they were going.

The ogre, when he woke, said to his wife, “Go up and dress those young rascals who came here last night.”

The ogress was very much surprised at this goodness of her husband, not dreaming of the manner in which she was to dress them; but, thinking he had ordered her to go up and put on their clothes, she went up, and was horrified when she saw her daughters all dead. She fell in a faint.

The ogre, fearing that his wife would be too long in doing what he had ordered, went up himself to help her. He was no less amazed than his wife at this frightful spectacle.

“Ah! what have I done?” he cried. “But the wretches shall pay for it, and that instantly.”

He threw a pitcher of water upon his wife’s face, and as soon as she came to herself he said, “Bring me quickly my seven-league boots, that I may go and catch them.”

He went out into the country, and after running in all directions he turned at last into the very road where the poor children were, not more than a hundred paces from their father’s house, to which they were running. They espied the ogre, who went at one step from mountain to mountain, and over rivers as easily as the narrowest brooks. Hop-o’-my-Thumb, seeing a hollow rock near the place where they were, made his brothers hide in it, and crowded into it himself, watching always to see what would become of the ogre.

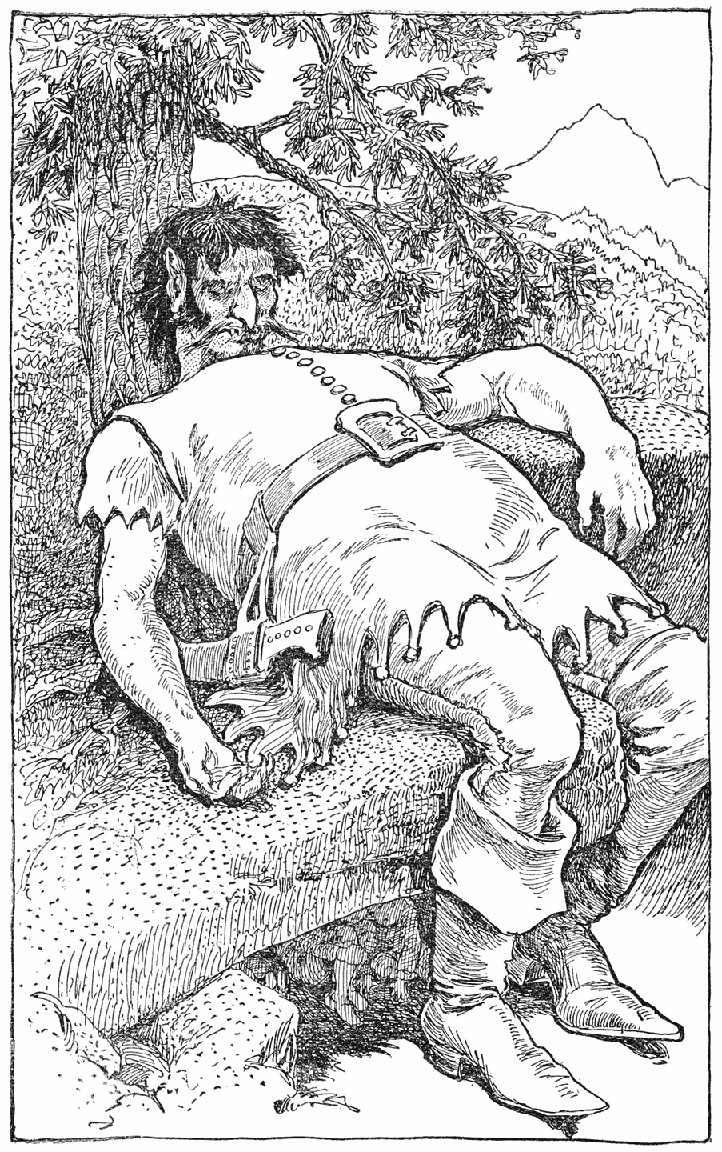

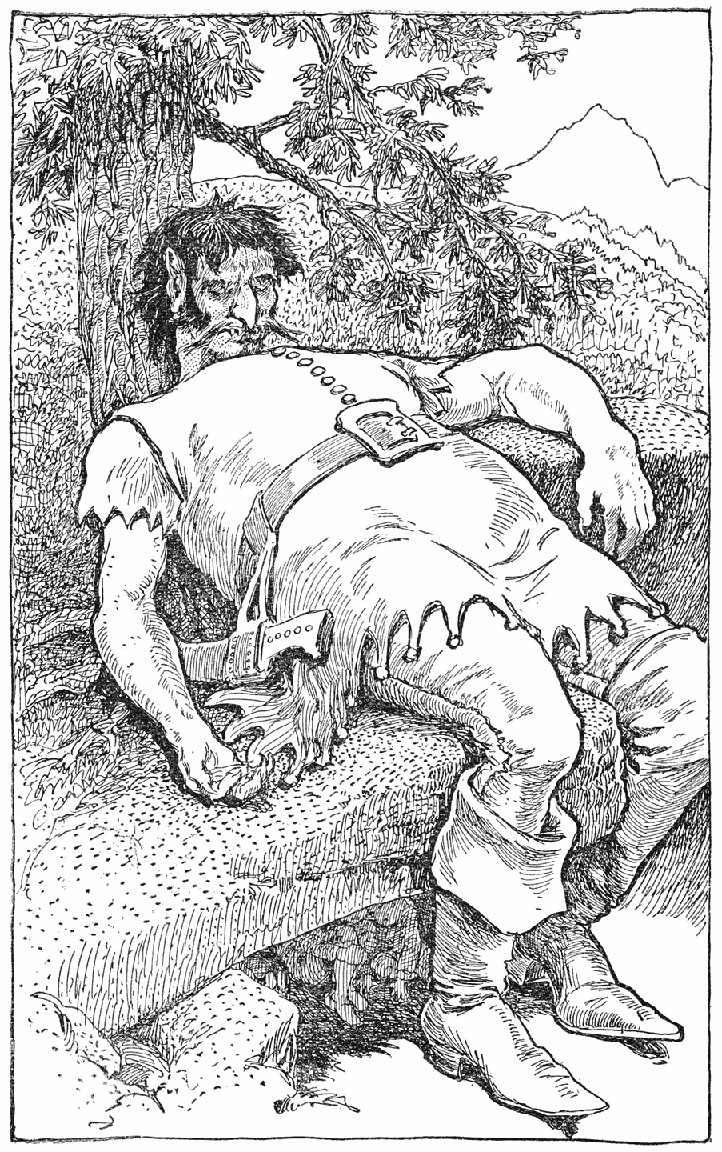

The ogre, who found himself very tired with his long and fruitless journey (for seven-league boots are very tiring to wear), had a great mind to rest himself, and happened to sit down upon the very rock where the little boys had hidden themselves. As he was completely worn out, he fell asleep, and began to snore so frightfully that the poor children were no less afraid of him than when he held up his great knife and was going to cut their throats. Hop-o’-my-Thumb was not so much frightened as his brothers. He told them to run quickly home, while the ogre was sleeping, and not to worry about him. They took his advice and soon got home safely.

Hop-o’-my-Thumb then went up to the ogre, pulled off his boots gently, and put them on his own legs. They were very long and large, but as they were fairy boots they had the gift of becoming big or little according to the legs of those who wore them; so they fitted his feet and legs as well as if they had been made on purpose for him.

As soon as Hop-o’-my-Thumb had made sure of the ogre’s seven-league boots, he went to the palace and offered his services to carry orders from the King to his army,—which was a great way off,—and to bring back the quickest accounts of the battle they were just at that time fighting with the enemy. He thought he could be of more use to the King than all his mail coaches, and so might make his fortune in this manner. He succeeded so well that in a short time he had made money enough to keep himself, his father and mother, and his six brothers (without their having to tire themselves out with working), for all the rest of their lives. He then went home to his father’s house, where he was welcomed with great joy. As the great fame of his boots had been talked of at court by this time, the King sent for him, and employed him on the greatest affairs of state; so that he became one of the richest men in the kingdom.

And now let us see what became of the ogre. He slept so soundly that he never knew that his boots were gone; but he fell from the corner of the rock where Hop-o’-my-Thumb and his brothers had left him, and bruised himself so badly from head to foot that he could not stir. So he was forced to stretch himself out at full length and wait for some one to come and help him.

Now a good many fagot-makers passed near the place where the ogre lay, and when they heard him groan they went up to ask him what was the matter. But the ogre had eaten so many children in his lifetime that he had grown so very big and fat, that these men could not have carried even one of his legs; so they were forced to leave him there. At last night came on, and then a large serpent came out of a wood near by and stung him, so that he died in great pain.

As soon as Hop-o’-my-Thumb heard of the ogre’s death, he told the King—whose great favorite he had become—all that the good-natured ogress had done to save the lives of himself and his brothers. The King was so much pleased at what he heard that he asked Hop-o’-my-Thumb what favor he could bestow on her. Hop-o’-my-Thumb thanked his Majesty, and desired that the ogress might have the noble title of Duchess of Draggletail given to her, which was no sooner asked than granted. The ogress then came to court, and lived happily for many years, enjoying the vast fortune she found in the ogre’s chests. As for Hop-o’-my-Thumb, he grew more witty and brave every day till at last the King made him the greatest lord in the kingdom, and set him over all his affairs.